Citrons in market in Syracuse, Italy. Giovanni Dall’Orto / wikimedia / 2014 / CC BY-SA 3.0

A citron tree is a small tree with large, light green leaves. It blooms with flowers that are purple on the outside, and then produces oblong fruit up to 20 cm (8 inches) long with very thick rough yellow peel.

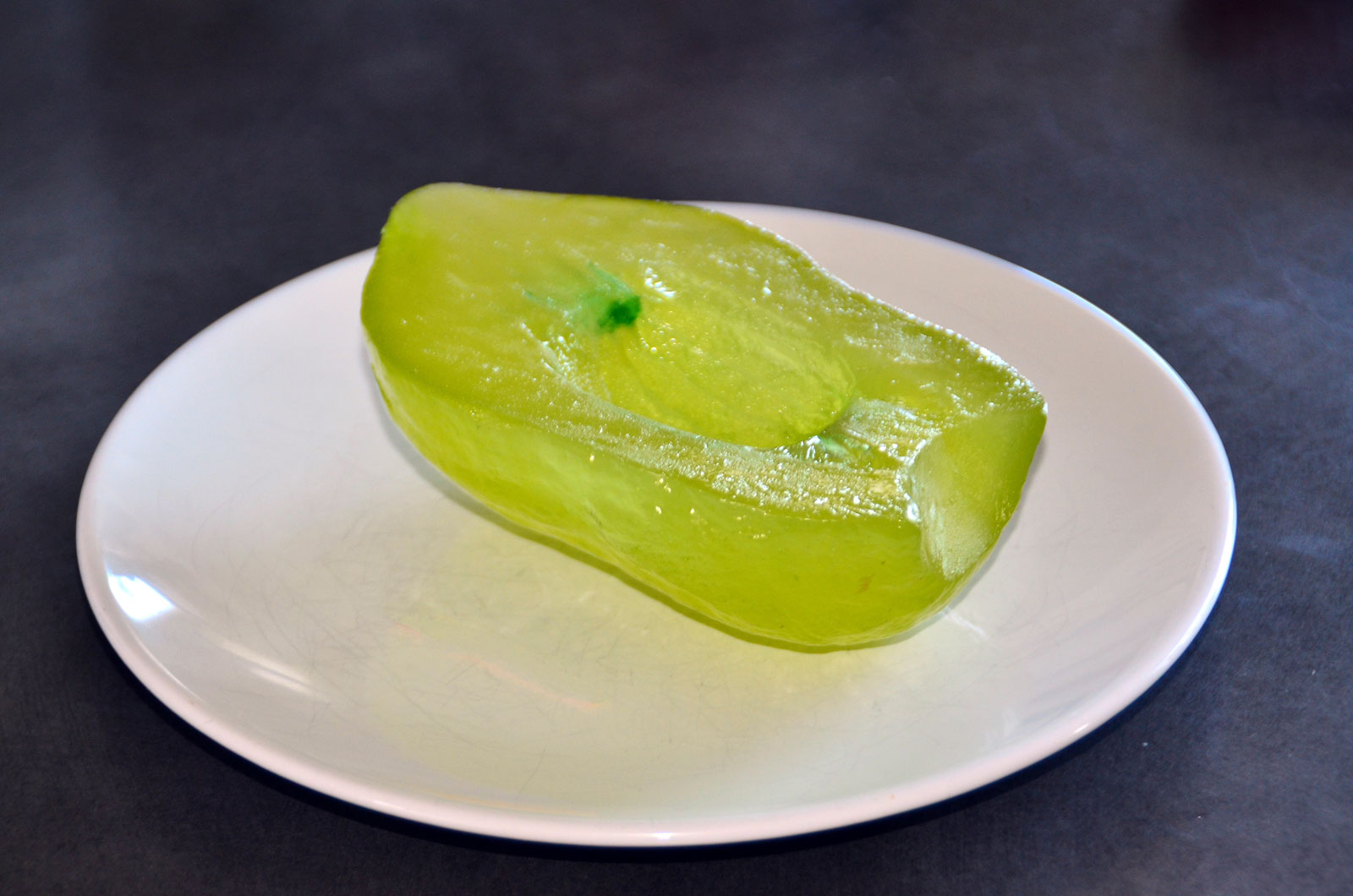

Inside the fruit, you see the white pith on the underside of the peel, as you do with other citrus fruit. The flesh of the fruit is greenish, and not very juicy (in some varieties, there is no juice to speak of at all.) So thick is the rind, though, there’s in fact not much flesh at all, and what there is, is very, very sour.

Citron cross-section. Richard Huber / wikimedia / 2014 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The fruit, though, is very fragrant; the scent of just a few in a bowl can fill a whole room.

In the modern times in the West the fruit is really only used for its peel, which is candied. To make the candied peel, the peel is first soaked in brine to cure it, then cut into small pieces and candied by simmering in a sugar syrup. This candied peel is used in Christmas cakes.

In other cultures, larger pieces of the thick white pith are candied in a similar manner. The citron gets halved, the pulp scraped out and the peel removed, then the remaining white pith is slowly cooked in a sugar syrup. In Greek, this dessert or sweet is known as “kitro glyko” (κίτρο γλυκό).

Candied citron half. Søren krabbe / wikimedia / 2013 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Citron varieties include Etrog citron and Buddha’s hand citron.

History Notes

Citron was the first citrus fruit. It was probably introduced to Middle East between 400 and 600 BC (there are the usual Alexander the Great stories, of course).

Romans and Greeks mostly grew it as an ornamental garden tree, and for some medicinal purpose, but they didn’t really draw on it for sour notes in their food.

The Greek medical writer, Galen (September 129 AD – c. 200/c. 216), said that citron was not easy to digest but that it was useful as a medicine:

“The citron has three parts, the acid part in the middle, the flesh, so to speak, that surrounds this, and the third part, the external covering lying around it. This fruit is fragrant and aromatic, not only to smell, but also to taste. As might be expected, it is difficult to digest since it is hard and knobbly. But if one uses it as a medicament it helps concoction, as do many other things with a bitter quality. For the same reason it also strengthens the oesophagus when a small quantity is taken.” (Galen, Properties of Foodstuffs, 2.37).

It was used to help women during pregnancy and labour:

Citron was also used in gynaecological treatments: Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) writes that pregnant women ate citron pips to avoid nausea in pregnancy (Natural History, 23.105) and the physician Soranus (from a similar date) explains that smelling citrons can help women in labour when they are very weak (Gynaecology, 2.2).” [1] Citrus fruits at Pompeii. Module 3, Health and Well-being in the Ancient World. Open University. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65957§ion=2.2

The greatest thing that citron may have done for us, however, is that it is probably the ancestor from which all other citrus fruit sprung.

Citron blossoms. Ruthtomaz / wikimedia / 2008 / Public Domain

Literature and Lore

Some people consider the Greek writer Theophrastus (c. 371 – c. 287 BC) to be the father of botany. He recommended citron for medicinal properties he supposed it had.

“Media and Persia have, among many others, that which is called the ‘ Median ‘ or ‘ Persian apple ‘ (citron). This tree has a leaf like to and almost identical with that of the andrachne, but it has thorns like those of the pear or white-thorn, which however are smooth and very sharp and strong. The ‘apple’ is not eaten, but it is very fragrant, as also is the leaf of the tree. And if the ‘apple’ is placed among clothes, it keeps them from being moth-eaten. It is also useful when one has drunk deadly poison; for being given in wine it upsets the stomach and brings up the poison; also for producing sweetness of breath; – for, if one boils the inner part of the ‘apple’ in a sauce, or squeezes it into the mouth in some other medium, and then inhales it, it makes the breath sweet. The seed is taken from the fruit and sown in spring in carefully tilled beds, and is then watered every fourth or fifth day. And, when it is growing vigorously, it is transplanted, also in spring, to a soft well-watered place, where the soil is not too fine; for such places it loves. And it bears its apples at all seasons; for when some have been gathered, the flower of others is on the tree and it is ripening others. Of the flowers, as we have said, those which have, as it were, a distaff projecting in the middle are fertile, while those that have it not are infertile. It is also sown, like date-palms, in pots with a hole in them. This tree, as has been said, grows in Persia and Media.” — Theophrastus. Enquiry into plants. Vol. 1. Translated by Sir Arthur Hort Sir for The Loeb Classical Library. London: W. Heinemann. 1919. Pp 311-313.

The Roman historian Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24–79) recommended the fruit as an insect repellent, as an antidote to poison, and to help pregnant women.

“There is another tree also with the same name of “citrus,” and bears a fruit that is held by some persons in particular dislike for its smell and remarkable bitterness; while, on the other hand, there are some who esteem it very highly. This tree is used as an ornament to houses; it requires, however, no further description.

The citron tree, called the Assyrian, and by some the Median apple, is an antidote against poisons. The leaf is similar to that of the arbute, except that it has small prickles running across it. As to the fruit, it is never eaten, but it is remarkable for its extremely powerful smell, which is the case, also, with the leaves; indeed, the odour is so strong, that it will penetrate clothes, when they are once impregnated with it, and hence it is very useful in repelling the attacks of noxious insects.

The tree bears fruit at all seasons of the year; while some is falling off, other fruit is ripening, and other, again, just bursting into birth. Various nations have attempted to naturalize this tree among them, for the sake of its medical properties, by planting it in pots of clay, with holes drilled in them, for the purpose of introducing the air to the roots; and I would here remark, once for all, that it is as well to remember that the best plan is to pack all slips of trees that have to be carried to any distance, as close together as they can possibly be placed.

It has been found, however, that this tree will grow nowhere except in Media or Persia. It is this fruit, the pips of which, as we have already mentioned, the Parthian grandees employ in seasoning their ragouts, as being peculiarly conducive to the sweetening of the breath. We find no other tree very highly commended that is produced in Media.

Citrons, either the pulp of them or the pips, are taken in wine as an antidote to poisons. A decoction of citrons, or the juice extracted from them, is used as a gargle to impart sweetness to the breath. The pips of this fruit are recommended for pregnant women to chew when affected with qualmishness. Citrons are good, also, for a weak stomach, but it is not easy to eat them except with vinegar.” [2] “Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book XXIII. The Remedies Derived from the Cultivated Trees, Chap. 56.—Citrons: Five Observations upon Them”.

Citron on tree, Sicily, Italy. Ji-Elle / wikimedia / 2011 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Language notes

Theophrastus (AD 23/24–79) gave the citron its first name in a Western European language, which was ‘apple of Media’ (“τό μηδικόν μῆλον”) before it later became ‘citron’.

“Naming fruits after their place of origin (or alleged place of origin) was a common practice among the Greeks and Romans: they called the peach the ‘Persian apple’, and the apricot the ‘Armenian apple’. These names signalled the exotic status of the trees and their fruits.” [3] Citrus fruits at Pompeii. Module 3, Health and Well-being in the Ancient World. Open University. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65957§ion=2.2

Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24–79) called it nata Assyria malus: Assyrian apple.

By the end of the 200s AD, it was no longer referred to as an apple variant and had acquired a name in its own right:

“The citron… was eventually given a simpler name: citrus in Latin and kitron in Greek… By the end of the 2nd century CE, Galen tells us that only pedants called the citron the ‘apple from Media’.” [4] Citrus fruits at Pompeii. Module 3, Health and Well-being in the Ancient World. Open University. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65957§ion=2.2

References

| ↑1 | Citrus fruits at Pompeii. Module 3, Health and Well-being in the Ancient World. Open University. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65957§ion=2.2 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, Book XXIII. The Remedies Derived from the Cultivated Trees, Chap. 56.—Citrons: Five Observations upon Them”. |

| ↑3 | Citrus fruits at Pompeii. Module 3, Health and Well-being in the Ancient World. Open University. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65957§ion=2.2 |

| ↑4 | Citrus fruits at Pompeii. Module 3, Health and Well-being in the Ancient World. Open University. Accessed May 2020 at https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=65957§ion=2.2 |