Olives and olive oil. Roberta Sorge / Unsplash / CC0 1.0

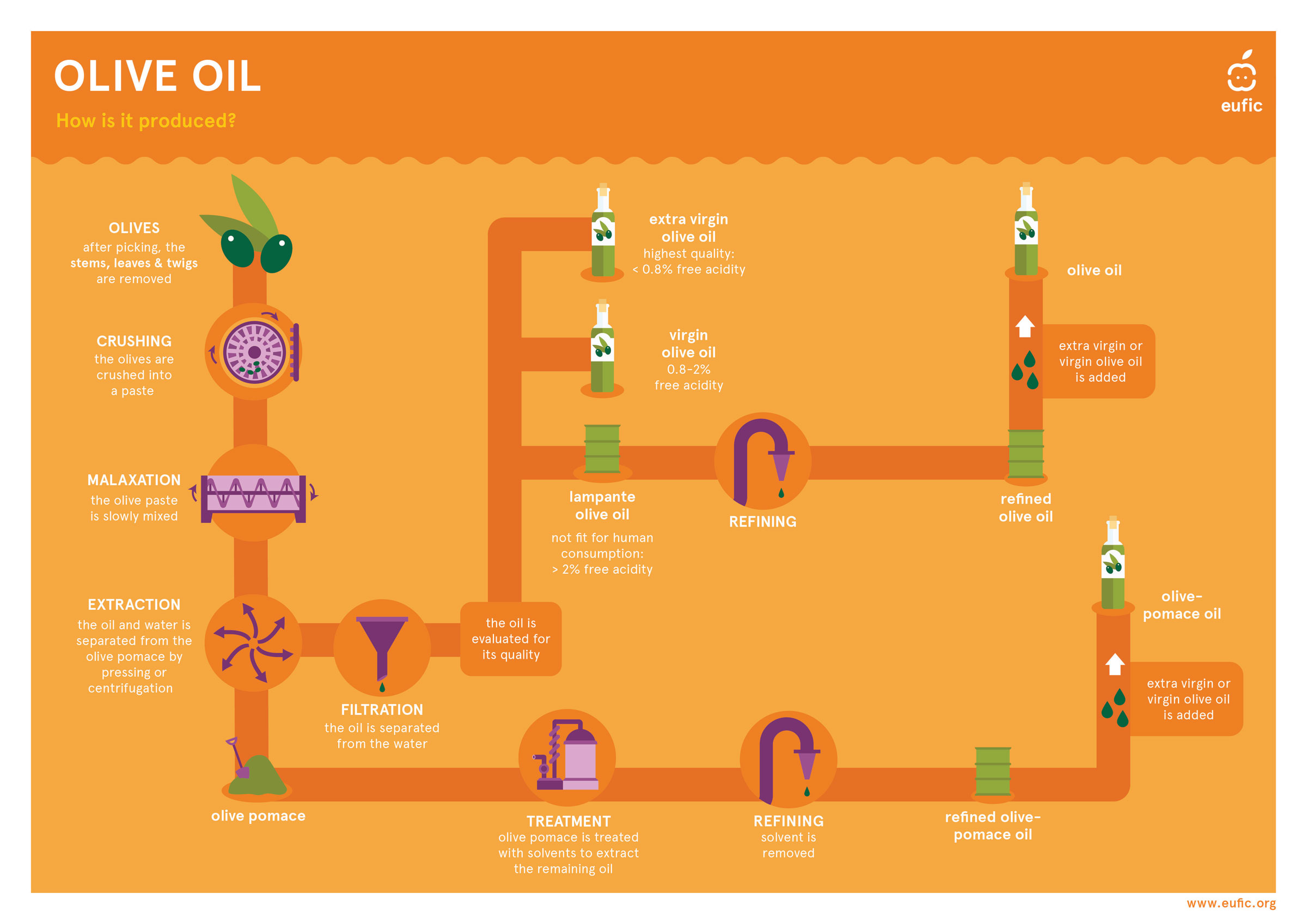

Olive oil is a liquid fat produced by pressing whole olives to force the juice out of them. The juice contains a blend of water and oil; it is then filtered to separate the oil.

Most people feel compelled to buy extra-virgin olive oil because industry marketing touts that as the best, using florid terms rivalling those of the wine industry. Unlike wine, however, olive oil does not improve with age.

That’s one of the reasons that the extra-virgin grade of olive oil may not be the best choice in all circumstances for all people. For many people, virgin olive oil or just regular olive oil may be a better choice, as they retain their quality longer in storage. And, in many instances, olive oil from regions other than Italy can be as good a choice as Italian.

Olive oil sources

When we think olive oil, we tend to think of Italy, though equally good ones are produced in Spain, Southern Greece and in North-West Crete.

Spain produces the most olive oil. Italy, especially Tuscany, specializes in extra-virgin olive oils. Classic blends of Tuscan olive oil use 4 olives: Frantoio, Correggiolo, Moraiolo, and Leccino.

Even though Italy and in particular Tuscany produce some of the world’s greatest olive oils, or at least some of the best marketed good ones, these aren’t the ones filling the shelves at our supermarkets. Not all olive oil labelled Italian is Italian. The Filippo Berio company in Lucca, Tuscany brings much of its olive oil in from Greece, Spain and Tunisia in tanker trucks because Italy can’t produce enough olive oil for its own needs, let alone for export. Bertolli olive oil does the same, though the Bertolli brand is not actually sold in Italy: the company produces olive oil under another name for the Italian market.

The consumer isn’t necessarily getting an inferior product, or being misled. Spanish and Greek olive oils can be as good or bad as the Italian ones, and the bottled olive oil is Italian to that extent that it’s blended and packaged in Italy, and has an Italian origin stamped on it. But nowhere does it say the oil is actually made from olives grown in Italy.

Consumers in North America and Italy tend to pay a little extra to get Italian olive oil and leave bottles labelled Spanish languishing on the shelves, because they’ve been taught that Italian is the one to buy. In actual practice, if you’re paying a lot of money for an Italian olive oil in a very fancy bottle, chances are that it really is from Italy.

Normal consumer price range olive oils, however, that are packaged in a way to give an impression of actually being Italian, are probably not really worth the price difference between them and Spanish olive oil, particularly given that they may be Spanish olive oil.

The situation may improve, at least for consumers in Europe. Legislation was effected in 2018 requiring greater truth about food origin in labelling:

“Since 2018 it has been mandatory – where the label specifies the origin of a food product (eg, ‘produced in Italy’, flag references, etc) but that differs from the origin of the primary ingredient (eg, tomatoes from China) – for the label to also state the origin of this primary ingredient. A primary ingredient is one that represents more than 50% of the food. A further EU regulation, which came into effect 1 April 2020, covers the implementation of this law – how to inform the consumer about ‘foreign’ primary ingredients, either by stating their origin or indicating that it’s different to that of the food.” [1]Understanding Food Labels. University of Reading / European Institute of Innovation and Technology. Module 1.12. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-labels/1/steps/795272

Grading olive oil

Technical classifications

There are two broad technical classifications of olive oils, virgin and non-virgin.

The European Union recognizes three categories of virgin olive oils:

- Extra virgin olive oil;

- Virgin olive oil;

- Lampante (not sold to consumers).

The following categories are non-virgin olive oils:

- Refined olive oil (made from lampante. Not sold to consumers in the EU.);

- Olive oil composed of a blend of refined olive oil and virgin olive oils;

- Crude olive-pomace oil (not sold to consumers);

- Refined olive-pomace oil.

Consumer classifications

For consumer purposes, the European Union recognizes four types of olive oil. These are the same as those recognized by the International Olive Council (IOC) and the U.S.D.A:

- Extra virgin olive oil;

- Virgin olive oil;

- Olive oil: Olive oil composed of refined olive oils and virgin olive oils;

- Olive-pomace oil.

Olive oil production flow chart. European Food Information Council.

Grading

Much of the grading is done by the acidity level of the oil:

- Extra-virgin: no more than .8 % acidity;

- Virgin: .8 to 2% acidity;

| IOC | EU | U.S. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extra-virgin | < .8 % | < .8 % | < .8 % |

| Virgin | < 2.0 % | < 2.0 % | < 2.0 % |

| Lampante | > 3.3 % | > 2.0 % | > 2.0 % |

| Pomace | < 1.0 % | < 1.0 % | < 1.0 % |

The United States is not a member of the IOC but has observer status. The U.S. moved in 2010 to harmonize its grading closer to that of the IOC. (See history below.) However, there is not at present any federal penalties in the U.S. for not adhering to proper labelling of olive oil grades:

“It is important to point out that the USDA standards are only voluntary and non-compliance bears no legal weight. In North America, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is the only country to have taken any pro-active legal action against the distribution of fraudulently labeled olive oil.” [2]Olive Oil Source. Refined Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoilsource.com/definition/refined-olive-oil

Some individual states such as California, Connecticut, New York, and Oregon have passed separate legislation strengthening truth in labelling requirements.

Types of olive oil

Extra-virgin olive oil

Extra-virgin olive oil. © CooksInfo / 2017

To make extra-virgin olive oil, the olives are mashed into a paste called the “pomace.” The pomace is then poured into a press and pressed to force the oil out. The oil is filtered, let settle, then filtered again. Some pomaces are pressed between millstones, some between metal crushers. Some people say metal alters the flavour.

To qualify as extra-virgin, the acidity of the resulting oil must be less than .8 % acidity. The lowest possible acidity is .225%. To get this low, the olives have to be pressed within 1 day of harvest. The longer they sit before processing, the more the acidity will rise.

The lower the acidity, the higher the quality. The oil will have a very olivey taste. Use it as a flavouring and accent oil. It has a smoke point of 208 C (406 F.)

In the olive oil industry, extra-virgin olive oil is often referred to by the abbreviation of EVOO.

Shelf life of extra-virgin olive oil (unopened)

This section applies to unopened bottles of olive oil.

Olive oil industry people typical cite an average shelf life for unopened bottles of extra-virgin olive oil of 18 to 24 months, and that range is cited by most food writers as well (food writers, though, often conflate unopened with opened).

The North American Olive Oil Association says that the following factors help determine a projected shelf life [3]North American Olive Oil Association. How long does olive oil last? February 2018. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.aboutoliveoil.org/how-long-does-olive-oil-last:

- olive varietal;

- fatty acid profile and polyphenol content;

- quality of the fruit;

- maturity of olives when harvested;

- harvesting method;

- milling/processing procedures;

- regional factors and conditions;

- blending practices.

Retailers and consumers need to bear in mind that “many external factors affecting shelf life, including package type, handling, and storage and merchandising conditions.” [4]North American Olive Oil Association. How long does olive oil last?. In other words, if you store the bottle of olive oil in a hot, sunny place, all bets are off.

Some recent independent research, though, suggests that the 18-24 months range is too optimistic an estimate, and should be 10-12 months instead:

“Seven cultivars of extra-virgin olive oils (EVOOs) with different contents of natural antioxidants were analysed to evaluate the influence of storage time on EVOO quality. The EVOOs were stored in 1-L-volume green glass bottles at room temperature (15–18 C) and with the same area of exposure to air. The main chemical, physicochemical, and sensory characteristics related to quality were determined for these EVOOs every 2 months, over a total period of 12 months. Under these storage conditions, all of the EVOOs showed gradual loss of quality. Based on these EVOO characteristics, the shelf-life was approximated to between 10 and 12 months, which is a lot shorter than the 18 months that is currently used for the expiry period.” [5]Serio, Maria Gabriella Di et al. “Shelf life of extra‐virgin olive oils: First efforts toward a prediction model.” Journal of Food Processing and Preservation . Vol. 42. 2018. DOI: 10.1111/jfpp.13663

In short, a bottle of extra-virgin olive oil is not something to set aside for years for a special occasion. It’s a “use it or lose it” proposition from the moment you buy it.

Shelf life of extra-virgin olive oil (opened)

Store an opened bottle extra-virgin olive oil only for a few months; use up by then. Store in a cool, dark place, in a tightly-sealed bottle.

The North American Olive Oil Association says,

“Once you have opened a bottle of olive oil, use it quickly — within 3 months. It will last longer if you store it in a cool, dark cupboard with a tightly sealed cap.” [6]North American Olive Oil Association. How long does olive oil last?

Bertoli says:

“Once a bottle of olive oil is opened, its shelf life depends on how the bottle is stored. A clear bottle with an ill-fitting cap that is placed in a sunny spot or by the stove will turn rancid very quickly and have an off-putting waxy smell, like a crayon or putty. That’s because exposure to light, oxygen and heat causes the oil to oxidize faster. Conversely, olive oil in a dark-tinted bottle that’s properly sealed and stored somewhere cool and away from light can last up to a few months.” [7]Bertoli. Olive Oil Shelf Life: How Long Does Olive Oil Last? Accessed September 2020 at https://essentials.bertolli.com/olive-oil-shelf-life/

Virgin olive oil

Virgin olive oil is a low-acid, very olivey tasting olive oil that you use as a flavouring oil. It is made from olives that are a bit riper than those used for extra-virgin olive oil.

To make the oil, the olives are mashed into a paste called the “pomace.” The pomace is then poured into a press and pressed to force the oil out. The oil is filtered, let settle, then filtered again. Some pomaces are pressed between millstones, some between metal crushers. Some people say metal alters the flavour.

EC regulations (EC Reg. 1513/01, which came into effect in 2002) allow virgin olive oil to have an acidity of up to 2%.

This might be a good oil to keep on hand instead of extra-virgin olive oil if you are an occasional user of an olive oil for flavouring purposes only. Its slightly higher acidity level gives it a far longer shelf life than extra-virgin: you can store it for up to two years. It has a smoke point of 215 C (420 F.)

Lampante olive oil

Clay olive oil lamp. 2246794 / Pixabay.com / 2001 / CC0 1.0

The word “lampante” in Italian refers to lamps. The term literally means oil for burning in oil lamps.

It is oil that is too high in acidity to be considered palatable for human consumption. It will have an unpleasant taste and smell. It could be because of the variety of olive, or that the olives were overripe when they were pressed. They could be olives so ripe that they had turned black and fallen off the tree and were on the verge of starting to rot. It could also come about owing to pest or frost damage to the olives.

Heat and water are often used to extract the maximum amount of oil from these olives. The resultant oil is very acidic.

The European Union defines it as having more than 2% acidity:

“Lampante olive oil is a lower quality virgin olive oil with an acidity of more than 2%, with no fruity characteristics and substantial sensory defects. Lampante olive oil is not intended to be marketed at retail stage. It is refined or used for industrial purposes.” [8]European Commission. Olive oil in the EU.

The International Olive Council defines it as having more than 3.3% acidity

“Virgin olive oil not fit for consumption as it is, designated lampante virgin olive oil, is virgin olive oil which has a free acidity, expressed as oleic acid, of more than 3.3 grams per 100 grams and/or the organoleptic characteristics and other characteristics of which correspond to those fixed for this category in the IOC standard. It is intended for refining or for technical use.” [9]International Olive Council. Designations and definitions of olive oils.

The U.S. defines it as having more than 2% acidity:

“(Aka) U.S. Virgin Olive Oil Not Fit For Human Consumption Without Further Processing” : “virgin olive oil which has poor flavor and odor (median of defects between 2.5 and 6.0 or when the median of defects is less than or equal to 2.5 and the median of fruit is zero), a free fatty acid content, expressed as oleic acid, of more than 2.0 grams per 100 grams, and meets the additional requirements as outlined §52.1539 as appropriate. Olive oil that falls into this classification shall not be graded above “U.S. Virgin Olive Oil Not Fit for Human Consumption Without Further Processing” (this is a limiting rule). It is intended for refining or for purposes other than food use.” [10]USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. Grades of Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.ams.usda.gov/grades-standards/olive-oil-and-olive-pomace-oil-grades-and-standards

Historically, such oil would have always had a ready market when people used oil lamps at home, but with the advent of electrical home lighting, that market would have melted away.

Refined olive oil

Refined olive oil is made from lampante oil, which is very acidic. The oil is neutralized in a refining process. The process leaves basically no flavour or smell.

The International Olive Council gives this definition:

“Refined olive oil is the olive oil obtained from virgin olive oils by refining methods which do not lead to alterations in the initial glyceridic structure. It has a free acidity, expressed as oleic acid, of not more than 0.3 grams per 100 grams and its other characteristics correspond to those fixed for this category in the IOC standard.” [11]International Olive Council. Designations and definitions of olive oils. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/

More than half of the olive oil produced in the Mediterranean area falls into this category.

“Over 50% of the oil produced in the Mediterranean area is of such poor quality that it must be refined to produce an edible product. Note that no solvents have been used to extract the oil, but it has been refined with the use of charcoal and other chemical and physical filters. An obsolete equivalent is “pure olive oil”. Refined oil is generally tasteless, odorless, and colorless.” [12]Olive Oil Source. Refined Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoilsource.com/definition/refined-olive-oil

Its sale is not allowed in some countries.

“This designation may only be sold direct to the consumer if permitted in the country of retail sale.” [13]International Olive Council. Designations and definitons of olive oils. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/ ”

“Many countries deem it unfit for human consumption due to poor flavor, not due to safety concerns.” [14]Olive Oil Source. Refined Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoilsource.com/definition/refined-olive-oil

The European Union does not allow the sale to consumers of refined olive oil by itself; it must be blended with some virgin olive oil:

“Refined olive oil is the product obtained after the refining of a defective virgin olive oil (lampante olive oil for instance). It is not intended to be marketed at retail stage. It has a degree of acidity up to 0.3%.” [15]European Commission. Olive oil in the EU. Accessed September 2020 at https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/plants-and-plant-products/plant-products/olive-oil_en .

It has a smoke point range of 199-243°C (390-470 F) [16]Olive Oil Smoke Point. Vancouver, BC: Selo Oils Inc. Accessed September 2020 at https://seloolive.com/blogs/olive-oil/olive-oil-smoke-point .

Olive oil

This is a standard cooking grade olive oil.

It is refined olive oil (see above), topped up with some virgin or extra-virgin oil to give flavour and colour — this virgin oil will constitute about 5 to 10% of the total product when done.

The EU defines it as:

“Olive oil composed of refined olive oil and virgin olive oils: an oil resulting from the blending of refined olive oil with extra virgin and/or virgin olive oils. It has a degree of acidity up to 1%.” [17]European Commission. Olive oil in the EU.

This olive oil has a good storage life, and is a good olive oil to cook with. It has a smoke point of 225 C (438 F.)

Olive pomace oil

Pomace olive oil. Trang-ten / openfoodfacts.org / CC BY-SA 3.0

The International Olive Council gives this definition:

“Olive pomace oil is the oil obtained by treating olive pomace with solvents or other physical treatments, to the exclusion of oils obtained by re esterification processes and of any mixture with oils of other kinds.” [18]International Olive Council. Designations and definitions of olive oils. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/

There are three levels of olive pomace oil:

- Crude: needs to be refined for either human consumption or technical use;

- Refined: has been refined from the crude. Its sale to consumers is banned in some countries.

- Olive pomace oil: a blend of the refined with some virgin added for flavour.

The solvents used in the extraction are organic solvents such as hexane, which are also used in extracting oils such as canola, corn, safflower and soy oil. The oil is then refined, and blended with some higher grades of olive oil to put some taste back in. It cannot legally be called olive oil; it must be called “pomace oil.”

This oil is fine for frying in. It has a smoke point of 460 F (238 C.)

There was a recall scare in 2001 with some pomace oils from Spain, but the production techniques were corrected after that.

Unofficial types of olive oil

The following are terms used by marketers that have no legal definition.

Cold-pressed olive oil

Cold-pressed olive oil. Extra-virgin olive oil. © CooksInfo / 2020

Extra-virgin and virgin olive oils are by definition are cold-pressed. This does not mean refrigerated, then pressed, but rather pressed without heating the olives (though given that most pressing is done in the winter, producers are allowed to bring the olives back up to room temperature.)

If you see any extra-virgin and virgin olive oils trumpeting the fact that they are cold-pressed, that’s marketing redundancy. Of course they are cold-pressed; that’s part of their definition. There’s nothing special happening here. The labelling might as well add “grown on trees.”

Light olive oil

Light olive oil. © CooksInfo / 2020

Light olive oil is a marketing term. There is no single authoritative definition of this term.

For the most part, it is used to mean refined olive oil (see above) to which no extra-virgin or virgin has been added, keeping the colour and taste light.

Be certain that the “light” refers to colour and the taste, not to the fat content. Some people suspect that marketers are happy to let people wrongly infer that a lower calorie level is also implied.

It provides a more general purpose oil for use in cooking where you don’t want a true, heavier olive oil taste to come through, such as in baking. [19]”Tasters found it as undetectable as vegetable oil in yellow cake.” America’s Test Kitchen. Light Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.cooksillustrated.com/how_tos/5711-light-olive-oil

It has a higher smoke point range than other olive oils of 199-243°C (390-470 F) [20]Olive Oil Smoke Point. Vancouver, BC: Selo Oils Inc. Accessed September 2020 at https://seloolive.com/blogs/olive-oil/olive-oil-smoke-point , so it is very good to fry in.

Its sale is not legal in some countries not for matter of safety, but because its quality is not seen as adequate.

Note however that because “light olive oil” is an “ungoverned term”, people can define it however they want.

Some people conflate the meaning with that of (regular) olive oil (see above), which is refined olive oil to which some virgin olive oil has been added. A writer in Bon Appetit says, “Light (Sometimes Called “Pure” or “Regular”) Olive Oil.” [21]Bilow, Rochelle. The Best Oils for Cooking, and Which to Avoid. Bon Appetit. 21 July 2017. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.bonappetit.com/test-kitchen/ingredients/article/types-of-cooking-oil Even America’s Test Kitchen gives it yet another definition, that of being oil from olives pressed a second time: “After the first press for extra-virgin oil, European producers squeeze the olives again and sell this flavor-stripped, highly processed oil to American consumers.” [22]America’s Test Kitchen. Light Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.cooksillustrated.com/how_tos/5711-light-olive-oil

Early season olive oil

This marketing definition sprang up in the early 2000s. It is made from very young olives, before they are fully ripe. This type of olive oil is a very dark green colour.

“Early-season olive oil is verdant green and piquant; late-harvest oil is golden and robust.” [23]Wu, Olivia. Fat is back. San Francisco, California: San Francisco Chronicle. 12 March 2003.

It is also marketed as having a very pronounced flavour:

“If we have never tasted an early-season olive oil, one that “burns” the throat, then we might accept as satisfactory any oil labeled, say, “extra virgin.” [24]Berandi, Gigi. FoodWISE: A Whole Systems Guide to Sustainable and Delicious Food Choices. North Atlantic Books. 14 January 2020. Food Choices: Experiences, Quality and Beliefs section.

Because very young olives don’t have as much oil in them as more mature ones do, more olives have to be used, making early season oil more expensive.

“Napa Valley’s fresh, tree-ripened olives are hand-picked and cold-pressed early in the year when they are dark purple in color, yielding an early harvest oil that is golden green with a fruity, smooth, sweet flavor. This is a bold, full-flavored buttery olive oil with a richly textured olive taste and a slight hint of pepper in the finish. It is ideal for dipping your best bread, tossing your freshest salad or drenching your ripest tomatoes. Early harvest extra virgin olive oils can be more expensive and harder to find than other extra virgin oils since unripe olives produce less oil and need to be picked right from the trees. Many people find their flavor, extra low acidity and higher antioxidant content worth the effort.” [25]Azure Vendor Marketing. Why You Should Try Napa Valley Organic Olive Oil. 16 September 2016. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.azurestandard.com/healthy-living/organic-olive-oil-from-napa-valley/

Olio Nuovo

Olio nuovo, unfiltered. Marga Reig / pixabay.com / 2013 / CC0 1.0

This is a marketing term meaning this year’s first batch of olive oil, akin perhaps to the wine world’s “beaujolais nouveau.”

It has a very pronounced grassy, peppery flavour. It is also touted for its presumed nutritional advantages:

“This is the first oil of the first olives of the new harvest, just pressed and bottled the same evening to keep the quality and the unmistakable fragrance intact… From a nutritional point of view, the new oil is the best, because the content of antioxidants and vitamins is higher. The right season to buy it is between the end of October and the end of November. “The new oil carries within itself all the typical characteristics of this food to maximum power” explains Ciro Vestita, professor of human nutrition at the University of Pisa. “You can recognize it immediately, even on sight: it is not clear, because it has many pectins in the fruit, such as chlorophyll , which will then precipitate. It has happened to everyone to find the classic “sediment” in the bottle, when it is nearly empty”. “All these components”, confirms Franco Spada, president of the Consorzio Olio Dop Brisighella, “give the typical bitter and pungent aroma of the new oil, which confirm the goodness of the product. Put on your plate it can have too much character to be used anywhere . For example, in a legume soup or on a bruschetta it is perfect, while on boiled fish or vegetables it can cover the flavors. For more delicate foods it is therefore better to wait a few months, so that these molecules settle. In any case, six months are sufficient, during which it loses very little of its nutritional value, acquiring instead a flavor, which becomes sweeter”. [26]Redazione OK Salute. L’olio extravergine nuovo è più nutriente? 5 March 2020. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.ok-salute.it/alimentazione/lolio-extravergine-nuovo-e-piu-nutriente/

It has a shorter life span because it is typically sold unfiltered:

“Some producers bottle the very first olive oil of the season and release it unfiltered and unracked. This ‘new oil’ is called ‘olio nuovo’ or ‘olio novello.’ These oils can taste fresh and delicious, but they will have a shorter shelf life since the unfiltered olive particles contain a little water which can lead quickly to degradation.” [27]Olio Nuovo? Olive Oil Times. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/faq/olio-nuovo

In Umbria, one producer turns the “new oil” time of the year into a time for promotional events for that year’s new harvest:

“Among the gentle Umbrian hills, in Montecchio, the days dedicated to the new extra virgin olive oil return every year in November… Excursions in the olive groves, music, delicious menus, the mill in operation and the real bruschetta. It’s just a small taste of what awaits you on the weekends dedicated to the New Oil celebrations. We look forward to seeing you at the next edition of Days of New Oil, in November 2020.” [28]Frantoio Bartolomei. È la festa dell’Olio

Nuovo. Accessed September 2020 at https://oleificiobartolomei.it/i-giorni-dellolio-nuovo/

Purchasing olive oil

Virgin olive oil, with its longer shelf life, as well as “plain” olive oil, which can be used for cooking, may actually be better choices to keep on hand for most people as everyday oils than the extra-virgin olive oil.

If you are only an occasional user of extra-virgin olive oil, you may wish to consider buying smaller bottles of that for table use, of a size that you can use up within a fewer months of opening, and buying a larger bottle of lower-grade olive oil to have on hand longer-term for cooking. This scheme also has the advantage of letting you sample more expensive, higher-grades of extra-virgin.

If you do buy large containers of extra-virgin because “it’s the deal of the century”, consider splitting with friends so it can be consumed before it goes off.

Some olive oils are bottled — and priced — like expensive wines. To taste olive oil, put a very small amount in your mouth, about ⅛th teaspoon, and roll it around in your mouth. Count to 6, spit it out, then take note of what you tasted at the start, in the middle and afterward. Some people feel that good ones will taste just a bit peppery at the end and leave no taste other than that, but preferences will vary.

Olive oil fraud

Olive oil fraud is an issue that has plagued Europe for several decades now. Deception can take place about both adulteration of the oil, and where it comes from. Profits can be comparable to cocaine trafficking, without the risks. [29] Mueller, Tom. Slippery Business: The trade in adulterated olive oil. New York: The New Yorker. 6 August 2007.

“The authenticity of olive oils is an important issue in Europe and involves both composition and origin.” [30]University of Reading. Understanding Food Labels. Case study: tomatoes and olive oil – where do they come from? Module 1.12. September 2020. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-labels/1/steps/795272

In 2008, olive oil fraud investigations in Italy led to the arrest of 23 people, and the discovery that €39 million Euros of olive oil sold as Italian was actually from non-Italian olives. They also caught people claiming EU farm subsidies for growing olives, even when they had imported the oil from elsewhere. [31]Moore, Malcolm. Italian police crack down on olive oil fraud. London: Daily Telegraph. 5 March 2008.

“In 2012 some Italian producers were found to have been blending Italian olive oil with cheaper oils imported from Spain, Greece, Morocco and Tunisia. And in 2016 Bertolli and Carapelli were found to be selling oil that didn’t meet the EU quality standards.

In 2018 the National Food Crime Unit in the UK discovered a case of olive oil adulteration where oil from Spain was being sold (and priced) as ‘extra virgin’ in the UK but was actually a blend of 30% refined and 70% extra virgin oil.” [32]University of Reading. Understanding Food Labels. Case study: tomatoes and olive oil – where do they come from? Module 1.12. September 2020. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-labels/1/steps/795272

Several measures are being taken to use technology to help fight olive oil fraud.

The International Olive Council (IOC) sets definitions of grading categories:

“The IOC develops standards of quality used by major olive oil producing countries, including Spain, Italy, Greece, Portugal, and Turkey. The IOC is an intergovernmental organization created by the United Nations that is headquartered in Madrid, Spain.” [33] Day, Lloyd C. Proposed United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil. USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. 27 May 2008. FR Doc. E8-12226. Printed in: Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 106 / Monday, June 2, 2008. Accessed September 2008 at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2008/06/02/E8-12226/proposed-united-states-standards-for-grades-of-olive-oil-and-olive-pomace-oil

Two countries notably not members are Australia and the United States: list of IOC members (link valid as of 2020).

Another measure being taken is an EU-funded project called “OLEUM” whose aim is to strengthen detection and prevention of olive oil fraud.

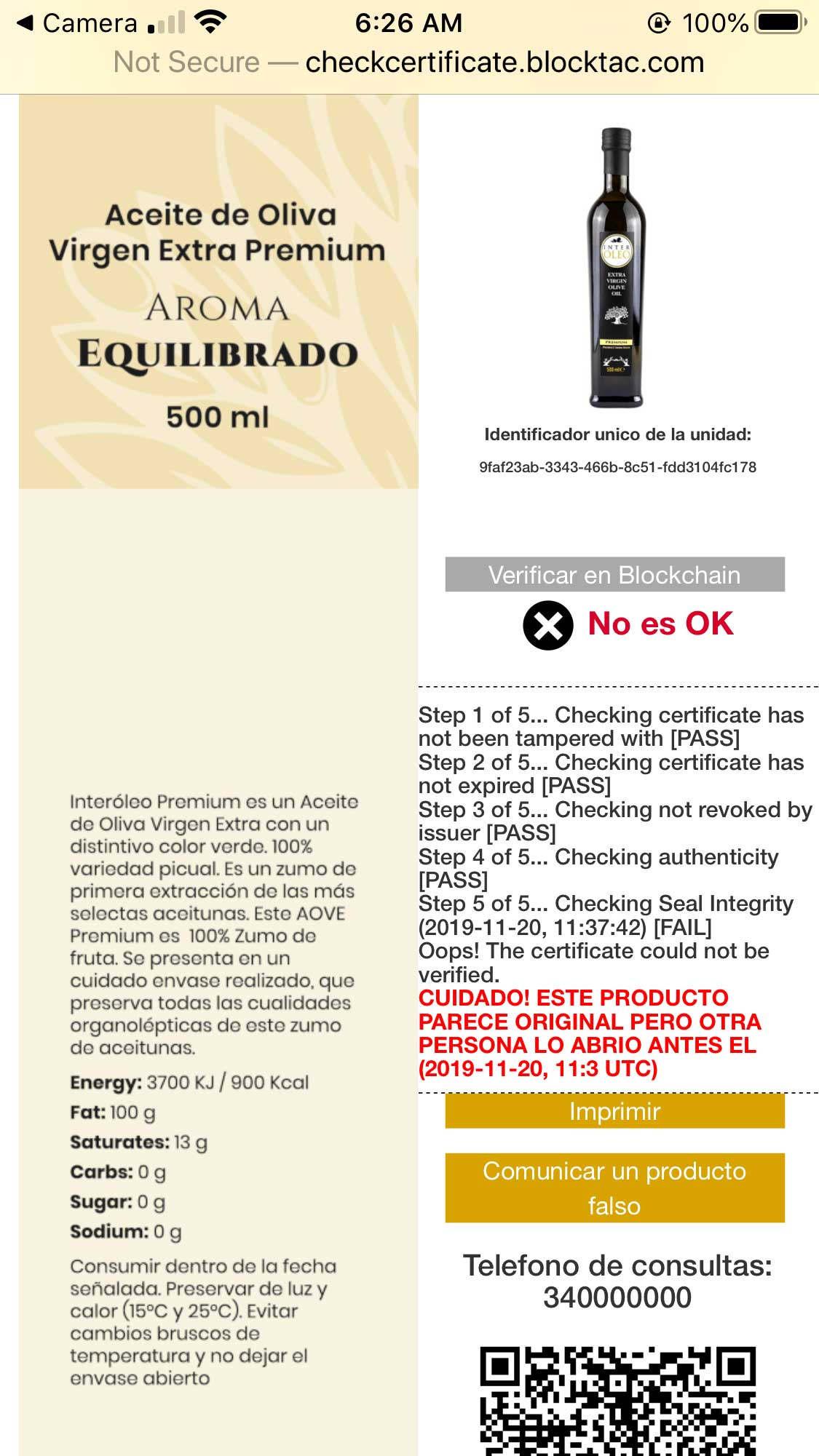

Another is a tool called “BlockTac.” It allows consumers to scan a QR code on a bottle of olive oil to track its path right back to its origin, and to see production details. BlockTac was first used in Spain and is now being rolled out to other countries (and is now being used for other foods as well.)

Scanning this QR code:

Src: https://www.blocktac.com/en/

Produces this result:

Src: https://www.blocktac.com/en/

The result above tells the consumer that a bottle bearing this QR code was opened long ago: and so that this one is probably a fake.

Cooking Tips

Julia Child said, in her classic “Mastering the art of French cooking”, warned people against using olive oil in classic French cuisine:

“Classical French cooking uses almost odorless, tasteless vegetable oils for cooking and salads. These are made from peanuts, corn, cottonseed, sesame seed, poppy seed, or other analogous ingredients. Olive oil, which dominates Mediterranean cooking, has too much character for the subtle flavours of a delicate dish. In recipes where it makes no difference which you use, we have just specified “oil”. [34] Child, Julia, et al. Mastering the Art of French Cooking. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1961. Vol. 1, page 19.

The phase transition for olive oil for its liquid to solid phase occurs at about -6 C (21.2 F).

Olive oil smoke points

There is no single authoritative source to go to for olive oil smoke points. In fact, you will almost certainly see different smoke points given for olive oil wherever you look:

“Extra virgin olive oil smoke points have been reported at a wide range from a medium heat oil at 165 °C to almost a high heat oil at 207 °C…. These differing reports could be attributed to many things. With much of the smoke point data being produced by commercial oil companies, it can be comfortably assumed that various methods were used to obtain these temperatures. This fact would allow for much variation in testing results. There could have also been smoke points included within a reported range that were of a different refining than the majority of the oils.” [35]Allen, Charles B, Jr. Thermal Degration and Biodiesel Production Using Camellia Oleifera Seed Oil. Univesity of Georgia. August 2015. Page 24 to 25.

Some researchers feel that it may be difficult to ever arrive at agreed-upon smoke points for olive oil, given the variables:

“According to Bastida and Sanchez-Muniz (2015) factors such as the oil variety, and the presence of stabilizing compounds act as confounders to the clear determination of VOO smoking point.” [36]Chiou, A. and Kalogeropoulos, N. (2017), Virgin Olive Oil as Frying Oil. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 16: 632-646. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12268

There is also the matter of subjectivity. It is up to the analyst testing for smoke points to decide at which point they feel an oil has started to emit smoke. Ideally, smoke points for any oil should be listed as a range.

That being said, here are some suggested smoke points for various olive oils:

- Extra-Virgin: 208 C (406 F) [37]”The smoke point for extra virgin olive oil is around 406°F.” Rodibaugh, Rosemary, and Katie Holland. Olive oil. University of Arksansas, Division of Agriculture. ;

- Virgin: 215 C (420 F);

- (Ordinary) olive oil: 225 C (438 F).

- Refined olive oil: 199-243°C (390-470 F) [38]Olive Oil Smoke Point.

As a general rule, 180 C (356 F) is considered a typical temperature for frying food in a pan, so the smoke point of all the above listed grades of olive oil are well above that.

Frying with olive oil

Popular wisdom has it not to fry with extra-virgin or virgin olive oils, as their smoke point is too low. For the same reason, people say, don’t use them in marinades. In fact, a minor hysteria swept the Internet for a few years about it being downright “toxic” to fry with olive oil.

The International Olive Council (IOC), perhaps unsurprisingly, feels that in fact olive oil is the ideal oil to fry food with:

“Olive oil is ideal for frying. In proper temperature conditions, without over-heating, it undergoes no substantial structural change and keeps its nutritional value better than other oils, not only because of the antioxidants but also due to its high levels of oleic acid. Its high smoking point (210ºC) is substantially higher than the ideal temperature for frying food (180ºC). Those fats with lower critical points, such as corn and butter, break down at this temperature and form toxic products.

Another advantage of using olive oil for frying is that it forms a crust on the surface of the food that impedes the penetration of oil and improves its flavour. Food fried in olive oil has a lower fat content than food fried in other oils, making olive oil more suitable for weight control. Olive oil, therefore, is the most suitable, the lightest and the tastiest medium for frying.

It goes further than other oils, and not only can it be re-used more often than others, it also increases in volume when reheated, so less is required for cooking and frying.

The digestibility of heated olive oil does not change even when re-used for frying several times.

Olive oil should not be mixed with other fats or vegetable oils and should not generally be used more than four or five times.” [39]International Olive Council. Frying with Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/#frying

Some independent research exists which backs the position of the IOC.

“When processed under normal cooking conditions, with temperatures up to 180 to 190 °C, as is common in frying, olive oil performance is comparable or better than other vegetable oils. Frying in olive oil provides the potential for improving the quality of fat intake, given that its incorporation into the fried food leads to a more favorable fatty acid profile that is high in MUFAs, and low in SFAs. Such a profile is beneficial for preventing cardiovascular diseases as indicated by the lowering of atherogenic and thrombogenic indices in fish and vegetables pan-fried in VOO. In addition, when VOO is used for frying, several health promoting microconstituents like phenolics, tocopherols, phytosterols, squalene, and terpenic acids, enrich the fried food and become part of our diet.

Compared with seed oils, VOO is preferable for frying, especially in home cooking (IOC). Under proper temperature conditions, without overheating, it undergoes no substantial changes and its performance is usually equal or superior to refined vegetable oils, due to its balanced composition regarding both major and minor components (Santos and others 2013). Olive oil contains 55% to 83% of monounsaturated oleic acid, which is 50 times less prone to oxidation than linoleic acid (Warner 2009), the polyunsaturated fatty acid that predominates in the majority of vegetable oils. Olive oil stands up well to high frying temperatures, as its high smoking point (210 °C) is well above the suggested temperature for frying food (180 °C; Bastida and Sanchez-Muniz 2015). Smoking point of VOO has been reported to be lower (160 to 170 °C; Bastida and Sanchez-Muniz 2015), although early studies (Detwiler and others 1940) had indicated a higher smoke point, that is 199 °C.” [40]Chiou, A. and Kalogeropoulos, N. (2017), Virgin Olive Oil as Frying Oil. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 16: 632-646. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12268

The Chiou and Kalogeropoulos study goes on to argue that frying with olive oil is actually healthier than with other oils. The argument is that during frying, the food absorbs food, so it’s better if the oil absorbed has the high nutritional profile that olive oil does. They point out that it could be through the act of frying in olive oil that the famed Mediterranean diet acquires its healthy oil intake:

“An interesting feature of fat intake in Spain and other Mediterranean countries was pointed out by Varela and Ruiz-Roso (1998) and by Ruiz-Roso and Varela (2001), who estimated that approximately 50% of total fat intake there is provided by cooking fats, namely fats used for the preparation of foods; a small fraction is consumed uncooked to dress foods and a significant amount is used for frying. The authors considered that the high intake of cooking fat in the Mediterranean countries offers a great potential for manipulating the quantity and quality of fat intake, which is not possible in other countries where the proportion of cooking fat is much lower. An example is from the Greek culinary economy: the pan-fried (in olive oil) fish and shellfish which provide significant amounts of energy due to the absorbed oil are traditionally served together with fresh salads or boiled greens, dishes of low fat content. Therefore, a typical meal containing fried fish is not expected to supply excess fat and energy.” [41]Chiou, A. and Kalogeropoulos, N. Virgin Olive Oil as Frying Oil. Page 634.

Some research showed that olive oil can lose its flavour around 60 C (140 F). Consequently, some people say not to waste very expensive extra-virgin olive oils in cooking, as the taste will not survive: reserve the finer ones for garnishing, table-use and salad dressings, and use lower grades for frying.

Nutrition

Olive oil is rich in healthy fats, and has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties.

“Olive oil is a vegetable fat containing a low concentration of saturated fat, which is palmitic acid, a high concentration of monounsaturated fat, that is oleic acid, the essential fat of olive oil, and some polyunsaturated fats, such as linoleic acids. In the oil there are about 200 minor components like squalene, carotenoids, phytosterols, tocopherols phenolics and some natural compounds like oleocanthal, oleruopein and hydroxytyrosol, influencing oil quality and properties such as flavor and taste… Many of the phenolic compounds contained in olive oil have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties which, together with the high content of monounsaturated fats, favorably impact on blood pressure and blood glucose control and reduce oxidation of the low-density lipoproteins, which made them more detrimental for atherosclerosis and the risk of having a heart attack. Finally, olive oil seems to have beneficial neuroprotective effects against chronic neurodegenerative disorders and, when included in the Mediterranean diet, it reduces by about 30% cardiovascular diseases and mortality.” — Defile, Corinna. Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin. Understanding Mediterranean and Okinawa Diets. Step 3.1: Seaweeds, mushrooms and tofu. Accessed February 2022 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/okinawa-diet/3/steps/1373391

Storage Hints

Store in a sealed container in a dark, cool place. Olive oil shouldn’t be refrigerated, but if it is, it will become cloudy and may develop white flakes. Restoring it to room temperature will make it clear again and the white flakes go away. It will not affect the flavour.

If you want to buy in bulk for the savings but it’s too much for you to use before it goes rancid, consider splitting with friends.

History Notes

Ancient olive press. Picky Junkie / Pixabay.com / 2016 / CC0 1.0

Olives were first cultivated in the Middle East. Cultivation probably didn’t reach Italy till in the 700s BC, brought by the Greeks to Southern Italy.

The Egyptians imported olive oil from the area that is now Syria and Palestine.

By 65 AD, production on the Italian peninsula was no longer enough to meet Roman demand. Importation started from Spain (particularly southern Spain) [42]Chavarria, Alexandra. Comparing food consumption in the Roman era and the Early Middle Ages. In: Enlightening the Dark Ages. University of Pavova. Online course. Step 2.5. Accessed November 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/enlightening-the-dark-ages-early-medieval-archaeology-in-italy/1/steps/1266915 — a situation which continues today.

Some historical researchers feel that it would be a mistake to look back at antiquity and assume that the olive oil was necessarily better then. Nancy Harmon Jenkins, a James Beard award winner and author of “Virgin Territory: Exploring the World of Olive Oil”, writes:

“Italy produced quantities of oil, not all of it premium by any means. Horace, the great Roman satirist of the late first century BCE, described the oil produced by his neighbor Ofellus: “You’d detest the smell of his olive oil,” he wrote, “yet even on birthdays or weddings or other occasions, in a clean toga, he drips it on the salad from a two-pint horn with his own hands.” [Horace, Book II, Satire II: 53-69.] Indisputably, most of the oil in antiquity was much worse than even the most ordinary oil that is available today. Milling procedures were primitive, and, despite what almost all the Latin agronomists recommended, little effort was made to produce oil cleanly and rapidly from sound olives at an early stage of maturity, so that it is no wonder the result was rancid, fusty, musty — all the characteristics that are overwhelmingly rejected by the best modern oil producers.” Jenkins, Nancy Harmon. Virgin Territory: Exploring the World of Olive Oil. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcout. 2015. Page 28.

Olive oil fraud was common in Antiquity, both in Classical Greece and Classical Rome:

“Olive-oil fraud was already common in antiquity. Galen tells of unscrupulous oil merchants who mixed high-quality olive oil with cheaper substances like lard, and Apicius provides a recipe for turning cheap Spanish oil into prized oil from Istria using minced herbs and roots.

Amphorae [Ed: recovered olive oil storage jars] show evidence of extensive anti-fraud measures: each was painted with the exact weight of oil it contained, along with the name of the farm where the olives were pressed, the merchant who shipped the oil, and the official who verified this information before shipment. Reverse checks were presumably performed… when the amphorae were emptied, to confirm that the weight and quality had not changed during shipment. “The biggest danger was that merchants would substitute an inferior product en route, and the explicit labelling of goods was clearly designed to counter this,” Mattingly said. In other words, the ancient Romans anticipated fraud… and took more effective steps to prevent it than Italians do today.” [43]Mueller, Tom. Slippery Business: The trade in adulterated olive oil. New York: The New Yorker. 6 August 2007.

While olive oil is highly valued now, in antiquity it had an importance far beyond that of today as it was pretty much the only oil — and was used for non-food purposes as well, such as lighting. Rome spread the market demand throughout the known world. The demand eased when Rome collapsed, and northern areas went back to using animal fat and other lesser oils.

Until about the 1960s, you could really only find olive oil in the UK at chemist shops (pharmacies).

In 2012, annual per capita consumption of olive oil was: Greece, 24 litres; Spain, 15 litres; Italy, 13 litres; Canada, 1.5 litres; USA, 1 litre. Overall, though, America was the third-largest olive oil purchasing country in the world: Italy consumed 21% of the world’s production, Spain 19%, and America, 9%. These overall figures would of course have reflected the size of the country’s population at the time. [44]June 2012. Retrieved from http://pmq.com/news/news.php?id=15997

U.S. olive oil grading changes in 2010

In 2010, the United States upgraded its olive oil grading to come closer to that of the International Olive Oil Council (IOOC).

In a 2008, after 4 years of comments and drafting, the proposed upgrade was released by the USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) wrote:

“AMS received a petition from the California Olive Oil Council (COOC), an association of olive oil producers, requesting the revision of the United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil to reflect current industry standards commonly accepted in the United States and abroad. The petitioners requested that the U.S. grade standards be revised to make them consistent with the International Olive Council (IOC) standards for olive and olive-pomace oil… ” [45] Day, Lloyd C. Proposed United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil.

One of the main ways they harmonized grading was in the percentage of acidity allowed in each grade. Previously, they had allowed the acidity level of extra-virgin to range up to 1.4 % (versus the international standards of .8%).

“One commenter… wanted the extra virgin olive oil free fatty acid level, expressed as oleic acid, to remain at a maximum of 1.4 percent, as in the current U.S. grade standards for “U.S. Grade A.” [46] Day, Lloyd C. Proposed United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil.

Literature & Lore

“An American going inland from the Atlantic coast is often surprised to find that olive oil, instead, of being served on every table, is exceedingly disliked.” — Rose, Mary Swartz. Everyday Foods in War Time. New York: Columbia University. 1918. From Kindle edition, 2012-05-16. Page 21.

Language Notes

“Virgin olive oil” is “Aceite virgen” in Spanish.

Sources

Bramen, Lisa. Where Does Your Olive Oil Come From? Washington, DC: Smithsonian Magazine. 10 March 2010.

Levy, Clifford J. “The olive oil Seems Fine. Whether It’s Italian Is the Issue”. New York Times, 7 May 2004.

References

| ↑1 | Understanding Food Labels. University of Reading / European Institute of Innovation and Technology. Module 1.12. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-labels/1/steps/795272 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Olive Oil Source. Refined Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoilsource.com/definition/refined-olive-oil |

| ↑3 | North American Olive Oil Association. How long does olive oil last? February 2018. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.aboutoliveoil.org/how-long-does-olive-oil-last |

| ↑4 | North American Olive Oil Association. How long does olive oil last? |

| ↑5 | Serio, Maria Gabriella Di et al. “Shelf life of extra‐virgin olive oils: First efforts toward a prediction model.” Journal of Food Processing and Preservation . Vol. 42. 2018. DOI: 10.1111/jfpp.13663 |

| ↑6 | North American Olive Oil Association. How long does olive oil last? |

| ↑7 | Bertoli. Olive Oil Shelf Life: How Long Does Olive Oil Last? Accessed September 2020 at https://essentials.bertolli.com/olive-oil-shelf-life/ |

| ↑8 | European Commission. Olive oil in the EU. |

| ↑9 | International Olive Council. Designations and definitions of olive oils. |

| ↑10 | USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. Grades of Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.ams.usda.gov/grades-standards/olive-oil-and-olive-pomace-oil-grades-and-standards |

| ↑11 | International Olive Council. Designations and definitions of olive oils. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/ |

| ↑12 | Olive Oil Source. Refined Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoilsource.com/definition/refined-olive-oil |

| ↑13 | International Olive Council. Designations and definitons of olive oils. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/ |

| ↑14 | Olive Oil Source. Refined Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoilsource.com/definition/refined-olive-oil |

| ↑15 | European Commission. Olive oil in the EU. Accessed September 2020 at https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/plants-and-plant-products/plant-products/olive-oil_en . |

| ↑16 | Olive Oil Smoke Point. Vancouver, BC: Selo Oils Inc. Accessed September 2020 at https://seloolive.com/blogs/olive-oil/olive-oil-smoke-point |

| ↑17 | European Commission. Olive oil in the EU. |

| ↑18 | International Olive Council. Designations and definitions of olive oils. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/ |

| ↑19 | ”Tasters found it as undetectable as vegetable oil in yellow cake.” America’s Test Kitchen. Light Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.cooksillustrated.com/how_tos/5711-light-olive-oil |

| ↑20 | Olive Oil Smoke Point. Vancouver, BC: Selo Oils Inc. Accessed September 2020 at https://seloolive.com/blogs/olive-oil/olive-oil-smoke-point |

| ↑21 | Bilow, Rochelle. The Best Oils for Cooking, and Which to Avoid. Bon Appetit. 21 July 2017. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.bonappetit.com/test-kitchen/ingredients/article/types-of-cooking-oil |

| ↑22 | America’s Test Kitchen. Light Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.cooksillustrated.com/how_tos/5711-light-olive-oil |

| ↑23 | Wu, Olivia. Fat is back. San Francisco, California: San Francisco Chronicle. 12 March 2003. |

| ↑24 | Berandi, Gigi. FoodWISE: A Whole Systems Guide to Sustainable and Delicious Food Choices. North Atlantic Books. 14 January 2020. Food Choices: Experiences, Quality and Beliefs section. |

| ↑25 | Azure Vendor Marketing. Why You Should Try Napa Valley Organic Olive Oil. 16 September 2016. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.azurestandard.com/healthy-living/organic-olive-oil-from-napa-valley/ |

| ↑26 | Redazione OK Salute. L’olio extravergine nuovo è più nutriente? 5 March 2020. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.ok-salute.it/alimentazione/lolio-extravergine-nuovo-e-piu-nutriente/ |

| ↑27 | Olio Nuovo? Olive Oil Times. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.oliveoiltimes.com/faq/olio-nuovo |

| ↑28 | Frantoio Bartolomei. È la festa dell’Olio Nuovo. Accessed September 2020 at https://oleificiobartolomei.it/i-giorni-dellolio-nuovo/ |

| ↑29 | Mueller, Tom. Slippery Business: The trade in adulterated olive oil. New York: The New Yorker. 6 August 2007. |

| ↑30 | University of Reading. Understanding Food Labels. Case study: tomatoes and olive oil – where do they come from? Module 1.12. September 2020. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-labels/1/steps/795272 |

| ↑31 | Moore, Malcolm. Italian police crack down on olive oil fraud. London: Daily Telegraph. 5 March 2008. |

| ↑32 | University of Reading. Understanding Food Labels. Case study: tomatoes and olive oil – where do they come from? Module 1.12. September 2020. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/understanding-food-labels/1/steps/795272 |

| ↑33 | Day, Lloyd C. Proposed United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil. USDA Agricultural Marketing Service. 27 May 2008. FR Doc. E8-12226. Printed in: Federal Register / Vol. 73, No. 106 / Monday, June 2, 2008. Accessed September 2008 at https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2008/06/02/E8-12226/proposed-united-states-standards-for-grades-of-olive-oil-and-olive-pomace-oil |

| ↑34 | Child, Julia, et al. Mastering the Art of French Cooking. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 1961. Vol. 1, page 19. |

| ↑35 | Allen, Charles B, Jr. Thermal Degration and Biodiesel Production Using Camellia Oleifera Seed Oil. Univesity of Georgia. August 2015. Page 24 to 25. |

| ↑36 | Chiou, A. and Kalogeropoulos, N. (2017), Virgin Olive Oil as Frying Oil. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 16: 632-646. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12268 |

| ↑37 | ”The smoke point for extra virgin olive oil is around 406°F.” Rodibaugh, Rosemary, and Katie Holland. Olive oil. University of Arksansas, Division of Agriculture. |

| ↑38 | Olive Oil Smoke Point. |

| ↑39 | International Olive Council. Frying with Olive Oil. Accessed September 2020 at https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/olive-world/olive-oil/#frying |

| ↑40 | Chiou, A. and Kalogeropoulos, N. (2017), Virgin Olive Oil as Frying Oil. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety, 16: 632-646. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12268 |

| ↑41 | Chiou, A. and Kalogeropoulos, N. Virgin Olive Oil as Frying Oil. Page 634. |

| ↑42 | Chavarria, Alexandra. Comparing food consumption in the Roman era and the Early Middle Ages. In: Enlightening the Dark Ages. University of Pavova. Online course. Step 2.5. Accessed November 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/enlightening-the-dark-ages-early-medieval-archaeology-in-italy/1/steps/1266915 |

| ↑43 | Mueller, Tom. Slippery Business: The trade in adulterated olive oil. New York: The New Yorker. 6 August 2007. |

| ↑44 | June 2012. Retrieved from http://pmq.com/news/news.php?id=15997 |

| ↑45 | Day, Lloyd C. Proposed United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil. |

| ↑46 | Day, Lloyd C. Proposed United States Standards for Grades of Olive Oil and Olive-Pomace Oil. |