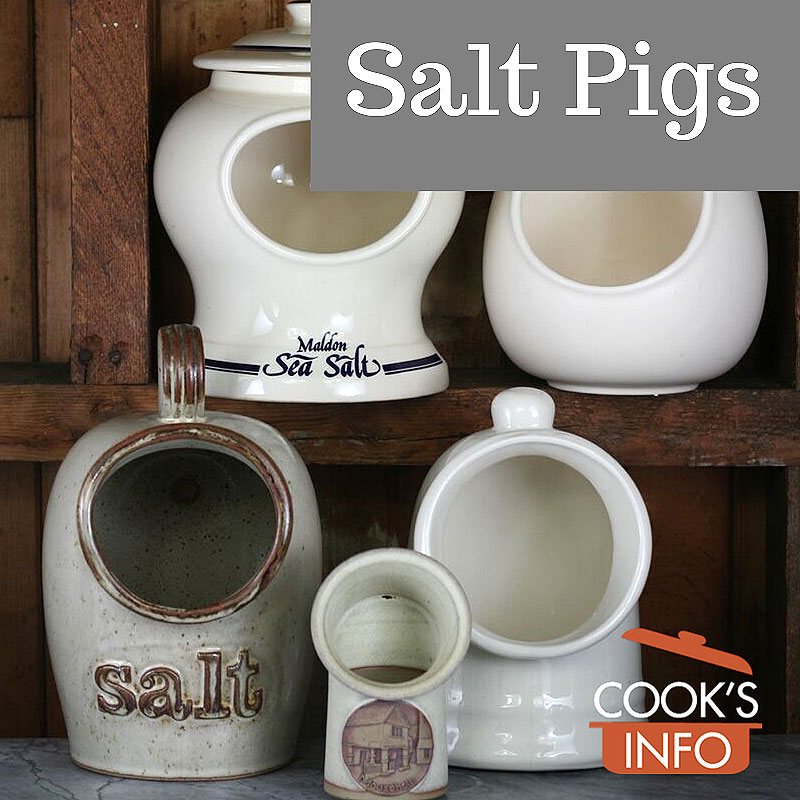

Salt pigs. © CooksInfo / 2018

Salt pigs are vessels for storing salt in. They are similar to a salt cellar. Their function, though, differs somewhat: they are meant for daily storage of salt in the kitchen, rather than fancy serving of it at the table. And in size, they are usually substantially larger.

Salt pig design

They are roughly cylindrical or ovoid, looking somewhat like an old fashioned diver’s helmet with a rounded top, a flat base, a knob at the top, and a wide (usually lipped) circular opening at one side.

The opening on the side provides quick access to the salt. The top and lipped opening keep dust and debris from settling in.

If you turn a classically designed salt pig on its side, to stand it on its opening, you’ll see that it resembles the back half of a pig. More modern designs, such as those by Nigella, resemble a pig less or not at all, and are likely not to have the knob at the top.

Salt Pig sideways, on its opening, showing pig shape. © Denzil Green / 2010.

Somehow the classic design keeps the salt dry even in humid weather and steamy kitchens. Some people assert that this is owing to unglazed insides of the salt pigs. Many salt pigs, however, have glazed interiors, and the salt stays just as dry. In fact, a John Hudson, an English potter and food historian and lecturer, warns: “Beware all unglazed salt-kits [Ed: salt pigs] especially in terra-cotta as the salt invades the body and causes spalling (flaking off) and eventually disintegration.” [1]Hudson, John. In White, Eileen. Ed. Feeding A City: York. Totnes, Devon: Prospect Books. 2000. Chapter 7.

Note, though, that fine-grained salt that doesn’t have anti-caking agents added may clump slightly on the surface in extremely humid weather if not used for a while, but a few pokes with a finger or spoon are sufficient to break that up when it occurs, which is extremely rare.

Salt pigs come in different sizes, made of different material. Some are porcelain, some are made of pottery. Most come with carved wooden spoons that hold exactly ¼ teaspoon of salt, which is handy for quick measurements.

When you want salt for a dish you are cooking, you reach into the large opening on the salt pig, and grab out pinches of salt for cooking. Larger salt pigs, obviously, will have larger openings and so be easier to reach into. With smaller ones, you’ll have to use the spoon, or tilt them to get the salt closer to the opening for your fingers.

Many people find that it is actually easier to control the quantity of salt being used when doing a pinch, rather than shaking from a shaker, and so use less salt, because they can see and feel exactly how much salt they are using.

Most people keep them on top of the stove, or on a counter nearby, for quick access, rather than storing them in a cupboard.

Many people also have several salt pigs, for different types of salt.

Safety

Is there a risk that the salt in a salt pig could be contaminated by hands not entirely clean?

Two food scientists, Dr Don Schaffner and Dr Ben Chapman, discussed this in a March 2020 podcast and feel that there is no risk of this happening. [2]Schaffner, Don and Ben Chapman. Salt Pigs. Risky or Not Podcast. 6 March 2020. 01:00 to 06:10. Accessed October 2020 at https://riskyornot.libsyn.com/salt-pigs

The reason, they say, is that salt is a poor disease vector. It is dry, and has sodium chloride, both of which work to inhibit bacteria.

Even if there were pathogens on someone’s hand and they put their hand into the salt, the salt would dry the pathogens out, just as salt is used to cure raw meat. “I’ll go so far as to say even if someone had been touching raw meat and not washed their hands, the salt would still be safe.”

They noted that though a lab strain of E-Coli ATCC 8739™ has adapted to 11% salt concentration, the environment in a salt pig is 100% concentration, and therefore completely hostile to any pathogen surviving in it.

Insecets — even houseflies — typically avoid the salt in salt pigs completely.

Salt pig with salt. © Denzil Green / 2003

History Notes

Historical food researcher John Hudson asserts that the original name is “salt kit”:

“The large hooded, flat-backed salt containers now called by most people salt-pigs (a term which came from one of the Sunday supplements or colour-comics as one of my friends calls them) a term which irritates me immensely…” [3]Hudson, John. Feeding A City: York

Nineteenth century models often had a loop handle as well as a knob at the top. [4]Pottery & Porcelain Glossary in: L. G. G. Ramsey, F.S.A., ed. The Complete Color Encyclopedia of Antiques. Preface by Bevis Hillier, Editor of The Connoisseur. Compiled by The Connoisseur, London. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc. 1962. Revised and Expanded Edition [5]Salt Kits. Description in Stoke Museums catalogue, accession number 1952 P7. Retrieved January 2010 from http://www.stokemuseums.org.uk/collections/browse_collections/ceramics/slipware_collection/salt_kits/000433.html

In this hearth, there was a niche in the wall off to the side of the fire. The salt pig would have been kept in that niche so that the salt in it was both handy and dry. Paul Merriam. Argyll’s Lodging, Stirling Castle, Scotland. 2014.

References

| ↑1 | Hudson, John. In White, Eileen. Ed. Feeding A City: York. Totnes, Devon: Prospect Books. 2000. Chapter 7. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Schaffner, Don and Ben Chapman. Salt Pigs. Risky or Not Podcast. 6 March 2020. 01:00 to 06:10. Accessed October 2020 at https://riskyornot.libsyn.com/salt-pigs |

| ↑3 | Hudson, John. Feeding A City: York |

| ↑4 | Pottery & Porcelain Glossary in: L. G. G. Ramsey, F.S.A., ed. The Complete Color Encyclopedia of Antiques. Preface by Bevis Hillier, Editor of The Connoisseur. Compiled by The Connoisseur, London. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc. 1962. Revised and Expanded Edition |

| ↑5 | Salt Kits. Description in Stoke Museums catalogue, accession number 1952 P7. Retrieved January 2010 from http://www.stokemuseums.org.uk/collections/browse_collections/ceramics/slipware_collection/salt_kits/000433.html |