Dish with heads medallion. Possibly Ptolemaic Egytpian or Punic. About 2nd century BC. Collected in Egypt. ROM, Toronto. cooksinfo / 2018.

Athenaeus was a classical Greek gourmand who was a citizen of the incredible interconnected, cosmopolitan Romano-Graeco world of the Mediterranean in classical times. He recorded culinary information about the world he lived in.

His world

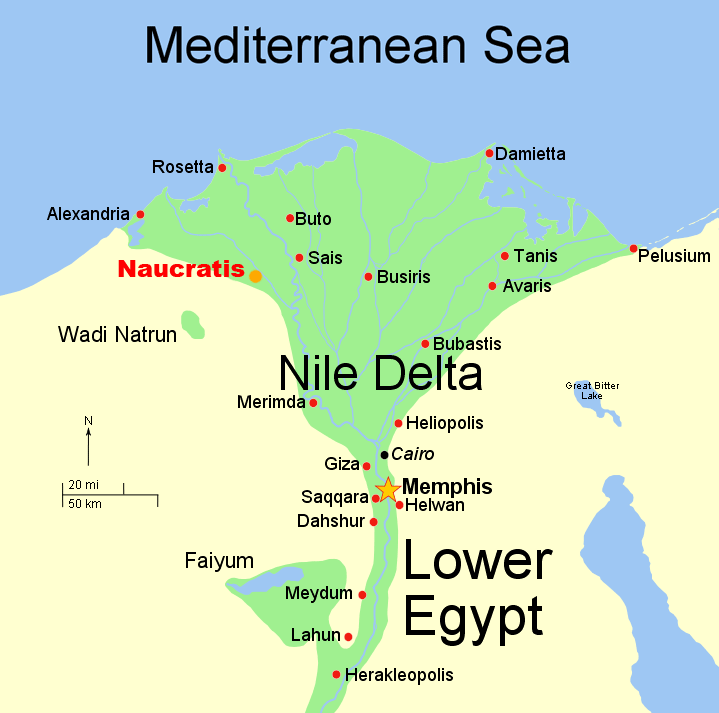

He lived in Naucratis, Egypt around 200 AD. [1]Some sources speculate that possible birth and death dates for him might be c.170–c.230 AD. Thus, he’s also referred to as “Athenaeus of Naucratis.”

Naucratis was between Memphis and Alexandria at the mouth of the western branch of the Nile River. Initially settled by Ionian Greeks in the 7th century BC, it had remained a prosperous Greek trading settlement, given special rights to be there by the Pharaoh. People from different parts of Greece even had their own neighbourhoods within the city. The city had temples to both Egyptian and Greek gods: Pharaoh Ahmose II even contributed toward the building of a Greek temple to maintain good relations with the Greek traders. Naucratis would have been a provincial backwater at the time of Athenaeus, far from any political power struggles, though the town had never been a political one. Its decline had begun after 300 BC and the founding of Alexandria, which eclipsed it as the premiere Greek city in Egypt. Nature also dealt it another blow, as the Nile shifted. Its ruins today are found near Nebireh, El Nibeira, 75 km south-east of Alexandria.

His writings

Though we don’t know much about his life, Athenaeus did leave behind books he had written. We know at least one book was lost, a history book called “On the Kings of Syria.”

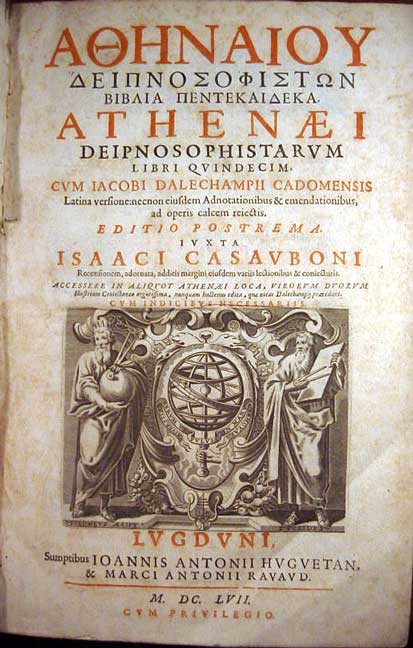

Athenaeus however, is best known in the food world for his book the “Deipnosophistae” (or “Δειπνοσοφισταί,” in Greek), and was probably written after 228 AD. In English it is often subtited “The Banquet of the Learned.”

There were 15 chapters altogether; 10 have come down to us intact, 5 we just have summaries of.

The book is a collection of anecdotes written in dialogue form that relates the table-chatter from at least three separate banquets given by a man named Laurentius at his home in Rome. The guests around the table (in the Greek fashion) were all men — though women were present in the room. All of the guests were of the leisured, learned Roman class — and the talk spanned a wide variety of subjects, including food, recipes, diet, health, famous fat people, sex, condiments, gravies, and pilafs. From chapter 8 (referred to now as Book VIII), we even learn the prices in Spain at the time of barley, wheat, wine, kid goats, hares, lambs, pigs, sheep, calves and figs.

We also hear about two other food books that were known at the time — one on breadmaking by Chrysippus of Tyana, and one on salted fish by Euthydemus of Athens. Sadly both books are lost to history. In fact, there are many Greek writers whose work was lost altogether, and it’s only thanks to Athenaeus’s chatty characters quoting them that we even have fragments of what they said. He also quotes a complete recipe from the Greek cook Mithaecus, the rest of whose cookbook has also been lost.

The book was first published in print in 1514 in Venice, with further printings in 1535 and in 1597.

You can download from Google Books a PDF version of the book. (Link valid as of August 2019)

Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, in five books, edited by Isaac Casaubon. 1657. Singinglemon / wikimedia / 2009 / Public Domain

Language Notes

“Athenaeus” (“Αθηναίος”) in Greek is pronounced “Athen-eye-us.”

Etymology of the word “deipnosophistae”

In Classical Greek, “depnon” (“το Δειπνον”) means “the meal” (in Athens, it meant more precisely the main meal of the day, e.g. dinner.) “Sofistay” (“σοφισταί”) meant “wise or learned ones”, from whence our word “sophisticates”. Thus, “deipno – sofistay”, or “dinner sophisticates.” More idiomatic English translations have included “The Gastronomers” and “Banquet of the Learned”. The closest of all translations might be the “Clever or Wise Dinner Guests” or “Dinner Table Philosophers.”

As an aside, also building on the word “dinner” (“depnon”), in Classical Greek “depno-loxos” (“Δειπνο-λοχοσ”) meant “to fish for an invitation for dinner.” Some things really are timeless.

Further reading

Naukratis: Greeks in Egypt. A British Museum project. Project findings at https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/research_projects/all_current_projects/naukratis_the_greeks_in_egypt.aspx (link valid as of August 2019)

References

| ↑1 | Some sources speculate that possible birth and death dates for him might be c.170–c.230 AD. |

|---|