Boxing Day. © Jason Gillman / Morguefile / 2016

Boxing Day, the 26th of December, is the day after Christmas. It is an official statutory holiday in some jurisdictions. In many places, the food eaten will be leftovers from the Christmas meal. In other places, a whole new meal will be cooked.

In Ireland and in Catalonia, it is celebrated as Saint Stephen’s Day.

It is the day when the after-Christmas sales start. Traditionally, the stores and main shopping thoroughfares would be heaving with weary shoppers looking for bargains. Boxing Day sales have lessened in importance now owing to the import of American Black Friday at the end of November, and online shopping.

#BoxingDay

Boxing Day as an official holiday

Boxing Day is an official holiday in Australia, Canada [1]In Canada, Boxing Day is a statutory holiday (as of 2005) only in the provinces of Ontario and Saskatchewan (though in Saskatchewan it’s decreed at the municipal levels.) People in other provinces will get it as a paid-day off work only if they are a federal government employee, or if they take it off as one of their allotted paid holiday days per year., New Zealand, and the UK [2]In Scotland only since 1974.. If it falls on a weekend, people will get the Monday off as well.

The day is mostly unknown in the United States. Most Americans have never heard of the day, or if they have, speculate that it’s the day to get rid of the empty boxes leftover from Christmas presents.

Servants got the day off, and got to go home to their families to have Christmas with them. [3]BBC. Why is it called Boxing Day? 28 December 2018. Accessed November 2020 at https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/46454700

The historical origins of Boxing Day

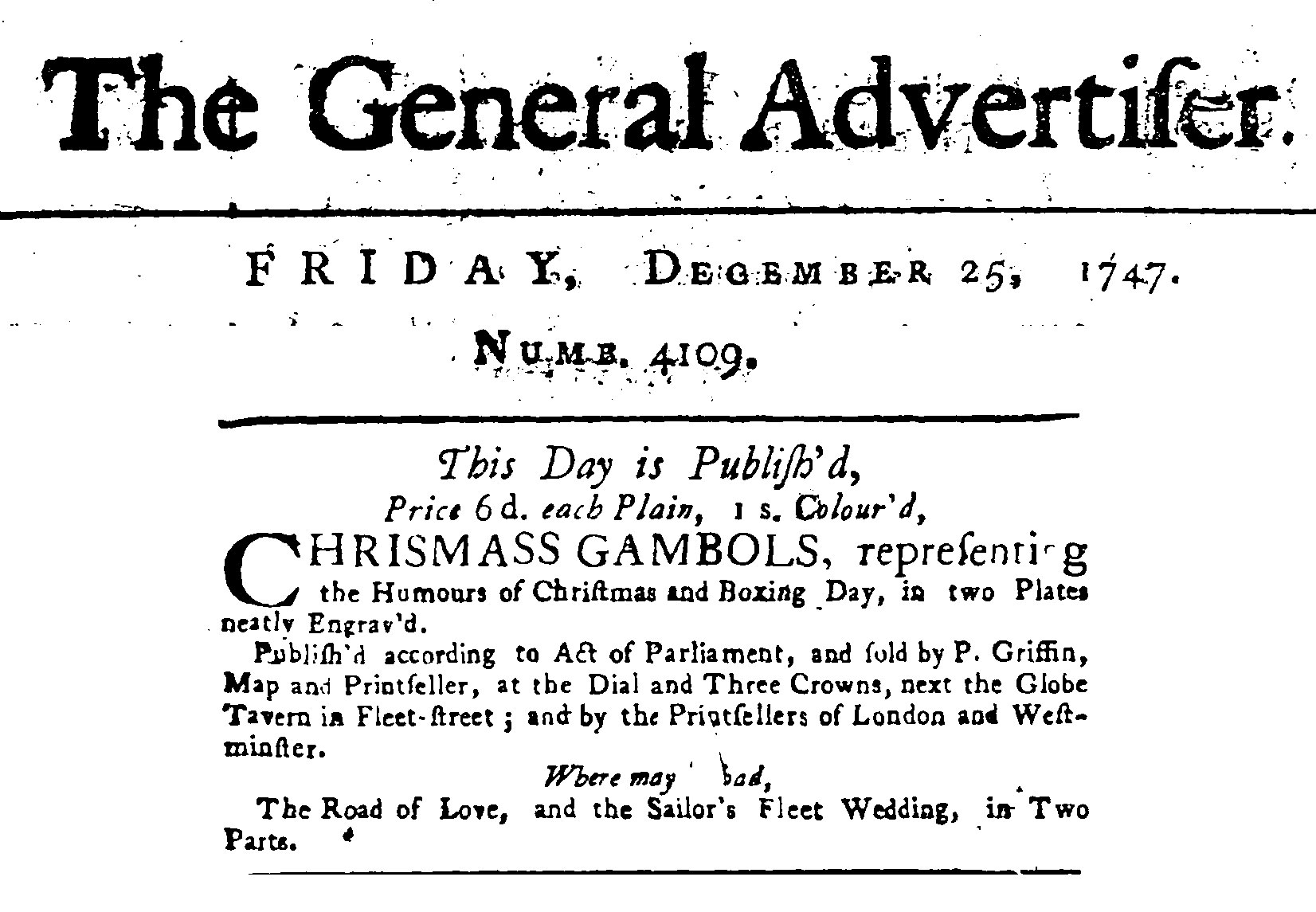

We find a mention of “Boxing Day” in an advertisement from 1747:

In: General Advertiser. London, Middlesex, England. 25 December 1747. Page 3, col. 1.

By the start of the 1800s, some writers of the period seem to have felt the day was past its prime — as will be seen by the newspaper excerpts below.

A few traditions seem to have come together to give Boxing Day its name, all to do with boxes, and even actual boxing (sic).

One was that on this day, it seems some poor people would carry boxes about asking for money donations into the boxes, so that these people might have the benefit of a post-Christmas mass held in their name. This tradition had disappeared by the start of the 1800s (if not earlier.) The Morning Post explained in 1825:

“Boxing Day: the Priests collected money formerly for masses, said to obtain forgiveness for the debaucheries of this merry season. The poor went about with boxes begging money, that they might have the benefit of the Priests’ masses also — hence Christmas boxes.” — Morning Post. London, England. Monday 26 December 1825. Page 3, col. 3

Another was that boxes were given out to poorer people, which seem to have sometimes at least contained cash:

“Then comes the great, the eventful day to the poorer classes, called Boxing Day, which is now divested of much of that real kindness and neighbourly feeling, which used to attend the gifts called Christmas-boxes; they are now too often given merely to get rid of a troublesome beggar, for seldom are they given with any other feeling; and, on the other hand, it but too frequently happens that the money is spent by those who receive it in low extravagance and debauchery. During the period of Christmas the New Year arrives, and with it another time for gifts; but these are fallen into a greater of disuetude than even the Christmas-boxes.” — A few thoughts on Christmas. Sheffield Independent. Saturday, 28th December 1822. Page 4. Col 3.

In another tradition, presents (in boxes, presumably) were given out on this day as yearly tips to people in service to you:

“The custom of Christmas gifts is of ancient origin, and now made on the day after, called Christmas Boxing day, from large families and establishments making presents to the apprentices and other persons, who come about soliciting a Christmas-box. The superstitious used to bleed and sweat horses on this day.” — Taunton Courier, and Western Advertiser. Somerset, England. Wednesday 04 December 1833. Page 8, col 2.

A writer for the Bucks Herald in 1834 said that recipients often took the cash and hit the pubs — hard — with it that evening:

“On the 26th of December last, the day commonly called ‘Boxing Day’, because on that day watchmen, lamp lighters, bill-stickers, cads, etc., etc., collect their Christmas-boxes in the morning, and then contrive to get pretty considerably fuddled towards sunset….” — Bucks Herald. Buckinghamshire, England. Saturday 11 January 1834. Page 2, col. 3.

Court reports in newspapers from that period show many people ended up spending a night in “watchmen’s cells” after being apprehended for disorderly conduct on Boxing Day night; the reports also recount their sessions with the magistrates the next morning on the 27th.

Perhaps because of the double meaning of “box”, both a noun and a sporting verb, the day also came to be associated with sporting events, including actual boxing itself. And not surprisingly, it seems that because many subsistence workers had suddenly came into a bit of cash, the sporting events were accompanied by gambling to relieve them of some if not all of that windfall.

The Sporting Varieties page for the Weekly Dispatch of London in 1822 appears to advertise an upcoming Boxing Day bull vs dogs fight (likely dogs genetically bred for the purpose, such as Staffordshire terriers, the first pit bulls):

“On the boxing day, next Thursday, Pritchard’s rumtitum [ed: bull. What is being described here is bull baiting, later to be outlawed in 1835] exhibit within four miles of London, for the amusement of the canine fancy. This is confessedly the finest game animal in the world. When he enters the ring, joy seems to sparkle in his countenance at the expected conflict. He waits with proud defiance for the approach of his assailants, each of whom he successively whirls into the air; and such is his skill in combat, that he scarcely ever allows one of these fierce and cunning foes to pin him. A pugilistic encounter between two nine stone men will wind up the sports of the day. It will be for a subscription purse.” — Weekly Dispatch (London). Sunday 22 December 1822. Page 8, “Sporting Varieties.”

In 1825, there is notice of an actual boxing event scheduled for Boxing Day:

“Boxing Day, of course, will be a rare day with all true boxers; at Jack Martin’s there will be an out-and-out to-do — the Prime of Life Club will muster in great force, as the chair is to be taken by the primest chaunter of the Fancy; and he will be faced by one of the very best of the batch.” — Weekly Dispatch (London). Sunday 25 December 1825. Sporting Varieties Page. Page 8, col. 2.

The disappearance and revival of Boxing Day

By 1834, Boxing Day had disappeared as a holiday. Perhaps it had fallen into some disrepute, owing to the wagering and gambling that had come to be associated with it owing to the sporting elements involved, but in fact, many holidays disappeared with the advent of the Industrial Revolutions. There were 47 bank holidays in 1761; by 1834, only 4 remained.

Boxing Day was restored in 1871 by the Bank Holidays Act, proposed by Sir John Lubbock. The act also restored Easter Monday, Whit Monday, and the first Monday of August. [4]Stewart, Graham. Past notes: Industrial Revolution brought an end to Boxing Day. London: The Times. 26 December 2009.

How Boxing Day is spent

People spend the day in different ways:

- Some use it as a day to give to the parts of your family that you didn’t spend Christmas Day with;

- Some prefer it as a day to do nothing;

- In many parts of Canada, many stores are open with post-Christmas sales. A lot of people race to the stores for bargains, and to return or exchange dud gifts that they got for Christmas (the standard joke goes that it’s called Boxing Day because shoppers may feel at the end of the day as though they had been in a boxing match.)

- Some people treat it as a day to use Christmas leftovers, particularly turkey. Many people make an effort to make up some kind of recipe from the leftover turkey, rather than just serving cold turkey sandwiches.

For many it’s a quiet day, to flick through the chocolates left in the trays that nobody wanted. Without the Christmas Day obligation of being sociable with uninteresting relatives, children get to settle in and enjoy their new toys. It has also come to be the day on which you try to wrestle children away from these toys and out to plays or special activities, if only to get them out of the house and out of mother’s hair for a while after the madness of Christmas Day.

In the UK, events held today include horse races, cricket matches, soccer games, annual icy dips in the sea or Channel, fox hunts and regattas. Banks and stores will be closed in the UK.

In Australia, there’s the Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, starting in Sydney Harbour, the Australian Boxing Day Cricket Test in Melbourne, horse-races, and sales. Some Australians use the day to start packing up the stuff from the Christmas holidays, and start to pack for their summer holidays.

Sydney to Hobart Yacht Race, Boxing Day. Sydney. 26 December 2005. © (Sarah Baker / flickr / 2005 / CC BY 2.0)

Literature & Lore

The Christmas Carol, Good King Wencelas, is set on Boxing Day (aka, St Stephen’s Day or “the Feast of Stephen”)

Stephen was possibly the first Christian martyr, mentioned in the Acts of the Apostles 6:1 to 8: 2. The carol was written by John Mason Neale (1818-1866) , an Anglican priest,. It appeared in his carol collection called “Carols for Christmas-Tide”, published 1853. The melody is actually from a 13th century medieval song whose words and melody were first published in 1352 in the Swedish/Finnish book “Piae Cantiones”. The song was called “Tempus adest floridum”, meaning “Now is the time of flowers”, referring to springtime. Wencelas wasn’t actually a King; he was a Duke, of Bohemia, in what is now the Czech Republic. If you pay attention to the carol, though Wencelas gets all the credit, it’s actually the servant doing all the work.

Boxing Day, or Christmas come again

This 1829 Boxing Day poem appeared in: Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. Sunday, 27 December 1829. Page 2. Col. 5.

It seems to refer to some of the old Boxing Day habits starting to fade.

Let good old customs ne’er decay,

Which we have priz’d of yore,

And let no man presume to say,

That boxing is no more.

For if with us the busy Beaks

Should dare to interfere —

We’ll give them for their meddling freaks,

A box upon the ear.

Then boxers pass the merry bowl,

And cast your cares away;

Then come with me, and take a stroll,

For this is Boxing-day.

Where are the Charleys, who at night,

In gentle slumbers doz’d?

The grisly groupes have vanish’d quite,

Their boxes all are clos’d

to boxing must they say adieu,

Mute is their tuneful tongue;

The lanthorn and the rattle took

Upon the willows hung.

Then boxes etc.

Swell scavengers and dustmen trim

Now run a boxing race,

And even the chimney-sweepers grim

Have washed their smutty face;

And in this time of general want,

When cash is very low,

With her large trunk, the elephant,

A boxing round may go.

Then boxers etc.

That boxing now is quite the rage,

We all may plainly see —

In Courts of Law, and on the stage,

With high and low degree.

Bold Wetherell, some mischief meant

Forgetting lawful labours;

And he and Sug were fully bent

On boxing like their neighbours.

Then boxers etc.

Now Quakers all, I pray beware,

Of leading naughty lives —

For well you know it isn’t fair,

To covet neighbours’ wives!

O, Gurney wherefore go astray?

Good principle it shocks;

But yet two thousand pounds, they say,

Is no bad Christmas box.

Then boxers etc.

Come brave Ned Neal, let’s have a dram,

Ere business we discuss —

And as you couldn’t box with Sam,

Why, come and box with us.

Time may, ere long, strange things reveal

As to the Petworth move;

And those who slander you, Ned Neal,

In the wrong box may prove.

Then boxers etc.

References

| ↑1 | In Canada, Boxing Day is a statutory holiday (as of 2005) only in the provinces of Ontario and Saskatchewan (though in Saskatchewan it’s decreed at the municipal levels.) People in other provinces will get it as a paid-day off work only if they are a federal government employee, or if they take it off as one of their allotted paid holiday days per year. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In Scotland only since 1974. |

| ↑3 | BBC. Why is it called Boxing Day? 28 December 2018. Accessed November 2020 at https://www.bbc.co.uk/newsround/46454700 |

| ↑4 | Stewart, Graham. Past notes: Industrial Revolution brought an end to Boxing Day. London: The Times. 26 December 2009. |