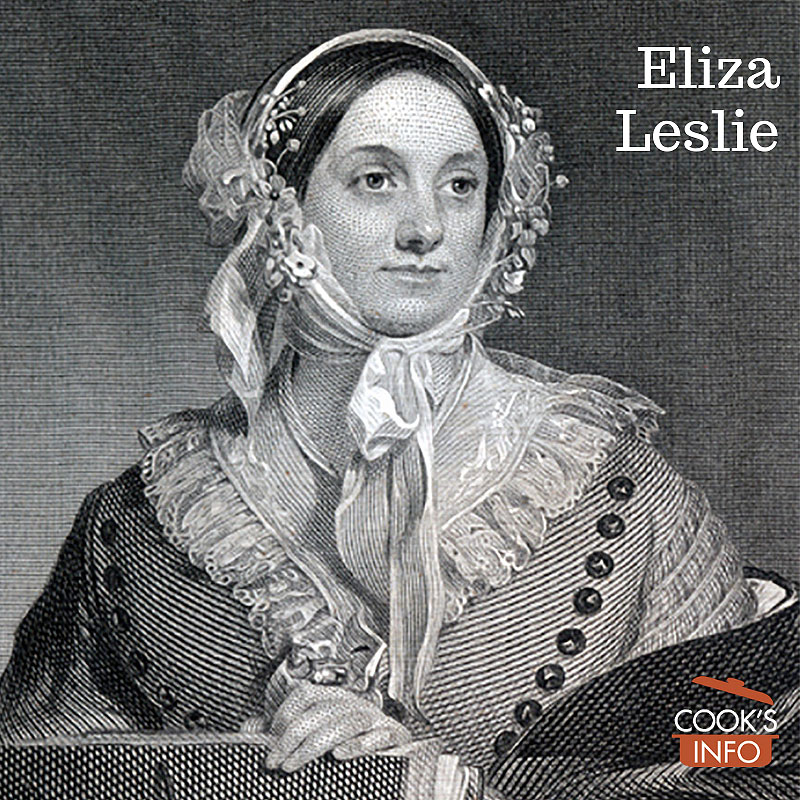

Eliza Leslie in: Godey’s Lady’s Book, Vol. 32/33, January to December, 1846, by Mrs. Sarah J. Hale; Edgar Allen Poe. Ekaterina Suvorova / wikimedia / 2016 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Eliza Leslie lived from 16 November 1787 – 1 January 1858 in Philadelphia.

She was a popular author of cookbooks, etiquette books and short stories. Her cookbooks, written in a strong, opinionated, witty style, found a ready audience in a burgeoning American middle class wanting to acquire both some food sophistication, and some manners to go along with it. She may also have published the first chocolate cake recipe in the United States.

Signature of Eliza Leslie. Src: Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography, 1900, v. 3, p. 696. Wikimedia / Public Domain

Early years

Leslie was born in Philadelphia on 16 November 1787. She was the first of five children born to Robert Leslie, a well-connected Philadelphia watchmaker, and Lydia Baker.

Leslie writes in a short autobiography:

“Soon after their marriage, my parents removed from Elkton to Philadelphia, where my father commenced business as a watchmaker. He had great success. Philadelphia was then the seat of the Federal Government; and he soon obtained the custom of the principal people in the place, including that of Washington, Franklin, and Jefferson, the two last becoming his warm personal friends. There is a free-masonry in men of genius which makes them find out each other immediately. It was by Mr. Jefferson’s recommendation that my father was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society. To Dr. Franklin he suggested an improvement in lightning rods,—gilding the points to prevent their rusting,—that was immediately, and afterwards universally adopted. Among my father’s familiar visitors were Robert Patterson, long Professor of Mathematics at the University of Pennsylvania, and afterwards President of the Mint; Charles Wilson Peale, who painted the men of the revolution, and founded the noble museum called by his name; John Vaughan, and Matthew Carey.” [1]Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. 1851. In: The Female Prose Writers of America: With Portraits, Biographical Notices, and Specimens of their Writings. Accessed August 2019.

Biographer Ophia Smith underlines the social position that Robert Leslie had obtained:

“In early nineteenth-century Philadelphia, the family of Robert Leslie was considered one of genius. Robert himself was a remarkable man — a self-taught scientist, musician and draughtsman, and a ready writer on scientific subjects. He was in the clock-and-watch business in the then seat of federal government, numbering among his patrons some of the most distinguished men of his time. It was through one of these patrons, Thomas Jefferson, that he was elected a member of the American Philisophical Society.” [2]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 512.

In 1788, a year after Eliza was born, his watchmaking business was at Second and Market Street in Philadelphia. [3]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. In: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. University of Pennsylvania Press. Vol. 74, No. 4 (Oct., 1950), pp. 512-527. Around this time, he took on a partner, and with a partner in place to help mind the shop in Philadelphia, he began developing plans to import products from England to Philadelphia.

When Eliza was five, in 1793, he moved the family to England to begin setting his plans in motion. “When I was about five years old, my father went to England with the intention of engaging in the exportation of clocks and watches to Philadelphia, having recently taken into partnership Isaac Price, of this city. We arrived in London in June, 1793, after an old-fashioned voyage of six weeks.” [4]Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography.

Eliza’s two brothers were born while they were in England, and possibly her two sisters as well. The children were largely educated at home, though there was a governess, and instructors who came in to give the children French and music lessons. She writes that as a child, she wrote many verses, but she destroyed them all when she entered her later teens, and set aside any thoughts of becoming a writer.

The Leslie family returned to live in Philadelphia in 1800. “We lived in England about six years and a half, when the death of my father’s partner in Philadelphia, obliged us to return home.” [5]Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography.

Biographer Smith gives more background info. It was not just a return, but a return to somewhat stressful circumstances: “In time, Leslie’s business became so large that he took a partner, Isaac Price, in order that he himself might live in London and export clocks and watches back to his concern in Philadelphia… When Isaac Price died, the Leslies returned to Philadelphia. The business had been woefully mismanaged, and the long and complicated court settlement left them much reduced in circumstances.” [6]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 512.

Three years after the return to Philadelphia, her father died. Eliza was 16. “After we came home [from London], my father’s health, which had long been precarious, declined rapidly; but he lived till 1803.” [7]Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography.

The family had to take in boarders; she, being the eldest child, helped her mother prepare the meals and run the establishment: “…Eliza, at the age of sixteen, and her mother were forced to open a boardinghouse in order to support the family.” [8]Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. New York: Oxford University Press. 2004. Page 255.

In the early 1820s, when she was in her early 30s, Eliza graduated from “Mrs. Elizabeth Goodfellow’s Cooking School” in Philadelphia. It was noted how studious she was because unlike the other students, she took copious notes.

Family

Any interaction between Eliza and her siblings must have been vibrant with interesting conversation. One of her brothers, Charles Robert Leslie (19 October 1794 – 5 May 1859) became a painter and a writer in England, where he married and stayed. He died a year after Eliza, in May 1859. Her sister, Anna Leslie, was also an artist. Her other brother, Thomas Jefferson Leslie (2 November 1796 – 25 November 1874) graduated from West Point and became a major in the Engineers of which he was also a paymaster. Her other sister, Martha (“Patty”), married Henry Charles Carey, a book publisher. [9]Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. [10]Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography. Eliza Leslie. Accessed August 2019.

Leslie herself never married: “Leslie never married, supporting herself by her writing.” [11]Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Page 255.

The world of writing

Despite being resigned in her teens to never being a writer, in the mid 1820s, she changed her mind and did try her hand at writing again. But not poetry. Instead, a cookbook. Published in 1827, “Seventy-Five Receipts”, her first cookbook as well as being her first book period, was a collection of the recipes that she’d picked up at the Goodfellow cooking school — thanks to her copious notes in class.

“It was not till 1827 that I first ventured “to put out a book,” and a most unparnassian one it was—“Seventy-five receipts for pastry, cakes, and sweetmeats.” Truth was, I had a tolerable collection of receipts, taken by myself while a pupil of Mrs. Goodfellow’s cooking school, in Philadelphia. I had so many applications from my friends for copies of these directions, that my brother suggested my getting rid of the inconvenience by giving them to the public in print. An offer was immediately made to me by Munroe & Francis, of Boston, to publish them on fair terms. The little volume had much success, and has gone through many editions. Mr. Francis being urgent that I should try my hand at a work of imagination, I wrote a series of juvenile stories, which I called the Mirror. It was well received, and was followed by several other story-books for youth…” [12]Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography.

She listed the ingredients separately, placing them before the directions.

“All the ingredients, with their proper quantities, are enumerated in a list at the head of each receipt, a plan which will greatly facilitate the business of procuring and preparing the requisite articles.” [13]Leslie, Eliza. Seventy five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats. Boston: Munroe and Francis, 1828.

This was the style in which the Goodfellow School gave its recipes to students. In later cookbooks, however, Leslie reverted to the old manner of burying the ingredients in the directions.

She wrote to a friend, Margaret Bailey in Cincinnati:

“I send you a new book of receipts which may probably be useful in your family. It is in very general use in Philadelphia, in which city the art of making cakes and pastry has greatly improved within a few years. The book is in such demand that Henry Carey has to send every few weeks to Boston (where it is printed) for a fresh supply. If these receipts are exactly followed, I can assure you, by experience, that all the things made from them will turn out well; very superior to any that can be bought in the shops, while the expense will not exceed one half.” [14]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 519.

In the book, she did not give any credit to the school or to Elizabeth Goodfellow (c. 1767-1851) who ran it. “When Seventy-five Receipts appeared, there was no mention of Mrs. Goodfellow, no attribution of any kind. Miss Leslie simply states that the recipes are ‘original’…In his introduction to a recent reprint of Seventy-five Receipts (Journal of Gastronomy, San Franciso, 1986), culinary historian W.W. Weaver carefully traces the recipes therein to Mrs. Goodfellow and indicates that the success of the book was probably based on a combination of two remarkable talents, ‘Miss Leslie’s as a writer and Mrs. Goodfellow’s as a cook.'” [15]Longone, Jan. From the Kitchen. In: The American Magazine and Historical Chronicle. Vol. 4, No. 2. Autumn-Winter 1988-89. Page 48, 49. [16]Reber, Patricia Bixler. Mrs. Goodfellow – raves from Miss Leslie and others. Researching Food History blog. 6 July 2015. Accessed August 2019.

Seventy-five Receipts was to have a long life as a popular cookbook:

“From its first printing in 1828, Seventy-five Receipts went on to become one of America’s most popular cookbooks. It went through at least twenty editions on its own by 1847, with additional printings of the ’20th edition’ being recorded as late as 1875.” It was also published as addenda to various other cookbooks; for example, it appeared with Mrs. Lee’s ‘The Cook’s Own Book’ more than a dozen times between 1833 and 1890.” [17]Longone, Jan. From the Kitchen. Page 48.

In 1832, she published “Domestic French Cookery.” She was not the author, but rather the translator. The title page lists these pages as being translated from someone named Sulpice Barué. But that is misleading, as he was not the author, either. A brilliant bit of footwork by researcher Jan Longone has discovered that the author of the recipes was in fact Louis-Eustache Audot, and Barué was his editor. [18]Ibid., Page 49.

In doing the translation, Leslie also simplified some items. For instance, to deglaze a pan the original recipe called for using white veal stock, and bouillon, which of course the cook would have had to make up first. Leslie changes that and directs the cook to simply use “water.” “Mettez dans la casserole un peu de blond de veau, du bouillon…” becomes “put into the stew pan a little warm water.” [19]Ibid., page 49.

Her next book in 1837, “Directions for Cookery: Being a System of the Art, in Its Various Branches” would prove to be the most popular American cookbook in the 1800s, and was reprinted over 60 times between 1837 and 1870: “In 1837, Miss Leslie brought out the ‘Domestic Cookery Book’, and in 1840 the ‘House-Book’, both meeting with immediate success. By 1840 forty thousand copies of the Cookery-Book had been sold, and by 1851 it was in its forty-first edition, no edition being less than a thousand copies.” [20]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 525.

In a short autobiography she wrote of herself in 1851, when describing her written work, the lion’s share of the ink goes to describing and listing her fiction short stories, and her venture into novels.

“Although Eliza Leslie’s cookbooks were reprinted dozens of times, Leslie maintained that her first love was fiction…” [21]Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink.

Yet, she admits, it was the cookbooks which were the bread and butter:

The works from which I have, as yet, derived the greatest pecuniary advantage, are my three books on domestic economy. The “Domestic Cookery Book,” [Ed: “Directions for Cookery”] published in 1837, is now in the forty-first edition, no edition having been less than a thousand copies; and the sale increases every year. “The House Book” came out in 1840, and the “Lady’s Receipt Book” in 1846. All have been successful, and profitable.” [22]Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography.

In 1846, Leslie released her first and only book that was published in England first before America. That was the book entitled “The Indian Meal Book” [Ed: Indian meal == “cornmeal.”]. It was published a year later, in 1847, in America.

It has been a mystery why it would have been published in England first, but biographer Jan Longone thinks she has puzzled it out:

“A most intriguing mystery revolved around the printing history of [The Indian Meal Book.] It has long been assumed that the first edition was published by Carey & Hart in Philadelphia in 1847. However, biographical ferreting has led me to two earlier editions, both published in London. Why, one might ask, would a book for using Indian (corn) meal, until then a much-despised article of food in Europe, be published in London? The date reveals it all. It was published to teach the Irish how to use cornmeal to survive the great potato famine… A phone call to culinary historian Alison Ryley, on the staff of the New York Public Library, unearthed their bedraggled copy of the first London edition, published in 1846. The Publisher’s Advertisement clearly states the purpose of the book: “The almost universal failure of the potato crop throughout England and Scotland as well as Ireland must inevitably produce distress among the poorer classes, that can only be alleviated by the introduction of some substitute for potatoes less costly than wheaten flour. Maize, or Indian corn, is generally admitted to be the best and most available, as it may be procured at little more than half the price of wheat, and is much more nutritious than the potato, while the vast continent of America is able to supply the British markets with almost any quantity required.” [23]Longone, Jan. From the Kitchen. Page 52.

What remains a mystery, as Longone points out a bit further on, is, why Leslie? How did the connection with her come to be made to write this book? Though Leslie does say in her preface to the English edition that she has lived in England and flatters herself that she has succeeded in making the directions clear to English cooks.

Also in 1846, in the States, Leslie published “The Lady’s Receipt-Book: A Useful Companion for Large or Small Families.” With this book, Leslie evolved from not just writing for a middle-class audience, but also helping to create one by giving them a guide for more refined living.

Biographer Anne-Marie Rachman at Michigan State writes, “Her intended readers, “[f]amilies who possess the means and the inclination to keep an excellent table, and to entertain their guests in a handsome and liberal manner . . .” would not be found squeezing the cheese curds through the cheesecloth, but selecting menus and caring for the many fine things in a middle class home. Half the book is dedicated to such care, ie., cleaning silver, laundering white satin ribbon, preserving white fur and oil-paintings, as well as tips for traveling by sea and writing a proper letter.” [24]Rachman, Anne-Marie. Leslie, Eliza, 1787-1858. Michigan State University Library Digital Repository. Accessed August 2019.

The measurements she gives in her cookbooks are not always precise. “She professed to believe in accurate measurements and provided tables of equivalencies, recommending an accurate scale and a set of tin cups in graduated sizes. Leslie sometimes violated her own precepts, however, calling for a “teacup of sugar” or “a small wineglass of brandy.” [25]Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Page 255.

Leslie wrote for Americans at a time when it was hard for them to get cookbooks that used ingredients, measurements and directions easily accessible to American readers, as most cookbooks were European:

“Historians have argued that Leslie was successful because she crafted recipes to appeal to the young country’s desire for upward mobility as well as a uniquely American identity. At the time she began writing, women primarily used British cookbooks; Leslie appealed to them with a distinctly American work. (She noted in the preface to Seventy-Five Receipts, “There is frequently much difficulty in following directions in English and French Cookery Books, not only from their want of explicitness, but from the difference in the fuel, fire-places, and cooking utensils. … The receipts in this little book are, in every sense of the word, American.”)” [26]Karp, Liz Susman. Eliza Leslie.

Of course now in modern times, the preponderance of cookbooks come out of the US, and it is European readers who must struggle to relate to the unique form of measurements that Americans use.

A curiosity perhaps is how, or if, Leslie tested her recipes. They were popular, so they must have worked, but writer Liz Susman Karp notes, “Leslie never managed her own kitchen, and often had others testing recipes for her” [27]Karp, Liz Susman. Eliza Leslie., and Leslie always maintained that her recipes were “tested.”

Final years

Eliza Leslie spent her final years as somewhat of a Philadelphia celebrity, living permanently at the United States Hotel on Chestnut Street. [28]The Unites States Hotel opened in 1826 on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. It was operated first by John Rea, and then by his son, Thomas C. Rea, who died in 1846. It was demolished in 1856, and a Bank of Pennsylvania erected in its place. Src: World Digital Library, accessed August 2019 at https://www.wdl.org/en/item/9417/

She was living in the hotel at least as early as 1848. An Ellen Bailey to wrote an Abbe Bailey James on 14 March 1848 of a visit she paid to Leslie at the hotel. “She [Eliza] has hanging in the parlor in the U. S. Hotel where she boards a portrait of B. Franklin taken by her sister…” [29]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 518.

Leslie became close friends with Alice B. Haven (aka Alice B. Neal), a well-known writer and editor of the times. Haven describes their first meeting:

“I was summoned from my room to receive some morning callers; and, among the rest, a kindly-looking person, past middle age, and filling amply a large easy-chair, put our her hand, and drew me to her with a friendliness among strangers. It was not my ideal of Miss Leslie, whom I had imagined younger, and with less embonpoint; but it was a pleasant reality, such a welcome from one I had so long looked up to. From that day, we were “a pair of friends, though I was young”… and eventually I became a frequent evening visitor in the parlor of the United States Hotel, then in its prime, where Miss Leslie was for years a special attraction to guests from all parts of the union.” [30]Haven, Alice B. “Personal Reminiscences of Miss Eliza Leslie.” Godey’s Lady’s Book 56. 1858. Page 346.

Leslie held strong opinions on many matters, it seems:

“She had the reputation of a brilliant woman with a sarcastic wit and heady opinions who frequently offended strangers but was warmly affectionate to relatives and friends and generous to the needy.” [31]Rachman, Anne-Marie. Leslie, Eliza, 1787-1858.

In fact, Etta M. Madden who edited a collection of writings by Leslie noted that “Leslie was believed by some to be a European, due to her acerbic comments about Americans.” [32]Madden, Etta M. Selections from Eliza Leslie. footnotes, page, 286. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. 2011.

In particular, she didn’t like people asking her how much money she made:

“Miss Leslie’s store of anecdotes and amusing criticism were unfailing. It has been said, by those who judged solely from the style of her social sketches, that Miss Leslie was sarcastic in conversation, a person to be afraid of. This was by no means so. With her decided character, she was naturally strongly prejudiced either for or against persons or things. This was all; and those who knew her many amiable and excellent qualities readily passed over trifling errors in judgement. Situated in this eddy of the stream of general travel, she had a most admirable study of human nature ever before her; and nothing strongly marked or ludicrous escaped her. She would constantly tell me of these things, and add: “Now, I shall use that some day; so don’t steal my thunder.”

In personal criticism, she was only unsparing towards anything that approached to ill-breeding, and, I recollect, particularly inveighed against the impertinent queries that almost entire strangers frequently subjected her to: as, ‘Now, Miss Leslie, do tell us how much Mr. Godey pays for one of your stories!’ ‘How many can you write in a week?’; or, ‘Isn’t your cookery-book bringing you in a fortune?’and, still more decided, ‘How much can you make in a year by writing?’

I should as soon think of asking them how much their husbands’ business amounted to, or how much of it they were allowed to spend,’ she would add.” [33]Haven, Alice B. Personal Reminiscences of Miss Eliza Leslie. Page 346.

Biographer Ophia Smith notes the dual opinionated but warm sides of Leslie:

“Some people feared Eliza Leslie, because of her penetrating sarcasm, but her admirers loved her for her candor and almost quixotic benevolence. That she had eccentricities that were hard to live with is evident in the family correspondence. She was loved by her family, but they could not cope with her peculiarities in her last years. She held very strong prejudices, but she always stood for right principles and aimed to be useful to society.” [34]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 526.

Despite her celebrity, and her strong opinions, Leslie still had a sense of humour and was very capable of using it at her own expense. In an 1847 letter to one of her nieces, she commented on a miniature painting made of her: “It is by no means as handsome as Sully’s portrait of me, and therefore a more correct likeness. . . .” [35]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 526.

In her last decade, Leslie reportedly suffered from being overweight, and could not walk easily.

She was working on a biography of John Fitch, a steamboat pioneer, at the time of her death. “As early as 1842, Eliza began to collect materials for a life of John Fitch, and although she devoted much of the last years of her life to it, it was never completed.” [36]Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 525.

“The Life of John Fitch”…lies half finished as she laid it aside about that time, compelled, by the inroads of a silent but fatal desire, to suspend any active exertion of mind or body. Still, she was able to employ herself in general affairs, and the revision of new editions of her books already in print, until a short time before her death… the evening of her life was calmed and strengthened by simple and trusting reliance in the faith of her childhood and marked by its public acknowledgement in the ratification of the baptismal vows then made. She was laid to her final rest beneath ‘the shadow of the cross’, in St. Peter’s churchyard, in the city of her birth, in what was, at the time of her baptism, a part of the venerable Bishop’s parish, after an active, useful, honored and almost blameless life.” [37]Haven, Alice B. Personal Reminiscences of Miss Eliza Leslie. Page 349.

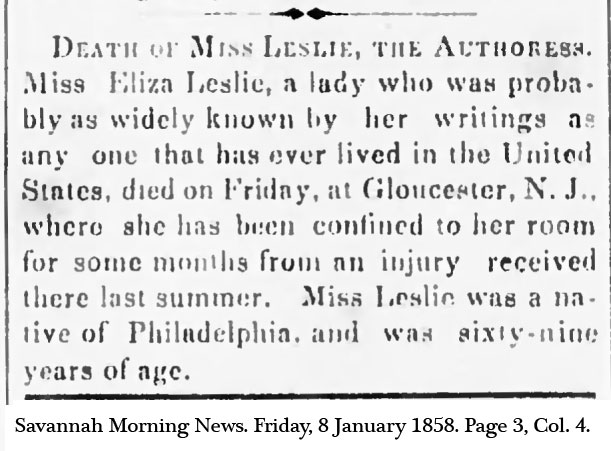

Leslie died in Gloucester, New Jersey, on New Year’s Day of 1858.

“The death of Eliza Leslie, the authoress, is announced as having taken place at Gloucester City, New Jersey, where she latterly had resided.” [38]Simpson, Henry. Eliza Leslie. In: The Lives of Eminent Philadelphians, Now Deceased. Philadelphia: William Brotherhead. 1859. Page 650.

The Unites States Hotel, where she had been living for a long time, was demolished two years before in 1856. This may have been the cause of her moving to Gloucester, or perhaps it was health that required the move before that even: “For many years, Miss Leslie lived in the United States Hotel on Chestnut Street across from the Second Bank of the US, but failing health caused her to move in with relatives in Gloucester, New Jersey, where she died…” [39]Hines, Mary Anne, et al. Eliza Leslie. In: The Larder Invaded. Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Philadelphia. 1987. Page 67.

An obituary in the Savannah Morning News says “Gloucester, New Jersery, where she has been confined to her room for some months from an injury received there last summer.” [40]Savannah Morning News. Friday, 8 January 1858. Page 3, Col. 4.

Eliza Leslie Obit.

She was buried in Saint Peter’s Episcopal Churchyard back in Philadelphia. [41]Eliza Leslie. Find A Grave. Accessed August 2019 at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/90396086/eliza-leslie.

Cookbooks by Eliza Leslie

Dates below are what we believe are the first publication dates. It can be hard to know as there have been so many editions and there is no one central place tracking editions of her work. E-books linked to may be editions published at subsequent dates.

- 1828. Seventy-Five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats, published by Munroe & Francis

- 1832. Domestic French Cookery (Leslie was the translator.)

- 1837. Directions for Cookery: Being a System of the Art, in Its Various Branches (directed at all classes of people)

- 1840. The house book, or, A manual of domestic economy. Philadelphia : Carey & Hart.

- 1843. Edited a magazine called “Miss Leslie’s Magazine. Home Book of Fashion, Literature and Domestic Economy.” Contained recipes, fashion, home care information, etc. Published from January of 1843 to July of 1846. After that, absorbed by ‘Godey’s Lady’s Book' [42] University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia Area Archival Research Portal (PAARP). Accessed August 2019 at http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/pacscl/index.html

- 1846. The Lady’s Receipt-Book: A Useful Companion for Large or Small Families (aimed at wealthier homes. Includes advice on cleaning silver and care of oil-paintings.)

- 1846. The Indian Meal Book (aka Corn Meal Cookery). London.

- 1850. Miss Leslie’s Lady’s New Receipt-Book

- 1851. Miss Leslie’s Complete Cookery Directions for cookery, in its various branches

- 1852. More receipts

- 1854. New Receipts for Cooking by Miss Leslie

- 1857. New Cookery Book

See also: Short stories by Eliza Leslie

Literature & Lore

“Pigs’ Feet, Fried: Pigs’ feet are frequently used for jelly, instead of calves’ feet. They are very good for this purpose, but a larger number is required (from eight to ten or twelve) to make the jelly sufficiently firm. After they have been boiled for jelly, extract the bones, and put the meat into a deep dish; cover it with some good cider-vinegar, seasoned with sugar and a little salt and cayenne. Then cover the dish, and set it away for the night. Next morning, take out the meat, and having drained it well from the vinegar, put it into a frying-pan in which some lard has just come to a boil and fry it for a breakfast dish.” — Eliza Leslie. New Receipts for Cooking by Miss Leslie. 1854.

“The best curry powder imported from India is of a dark green color, and not yellow or red. It has among its ingredients, tamarinds, not preserved, as we always get them — but raw in the shell. These tamarinds impart a pleasant acid to the mixture. For want of them, use lemon.” — Eliza Leslie. New Receipts for Cooking. 1854.

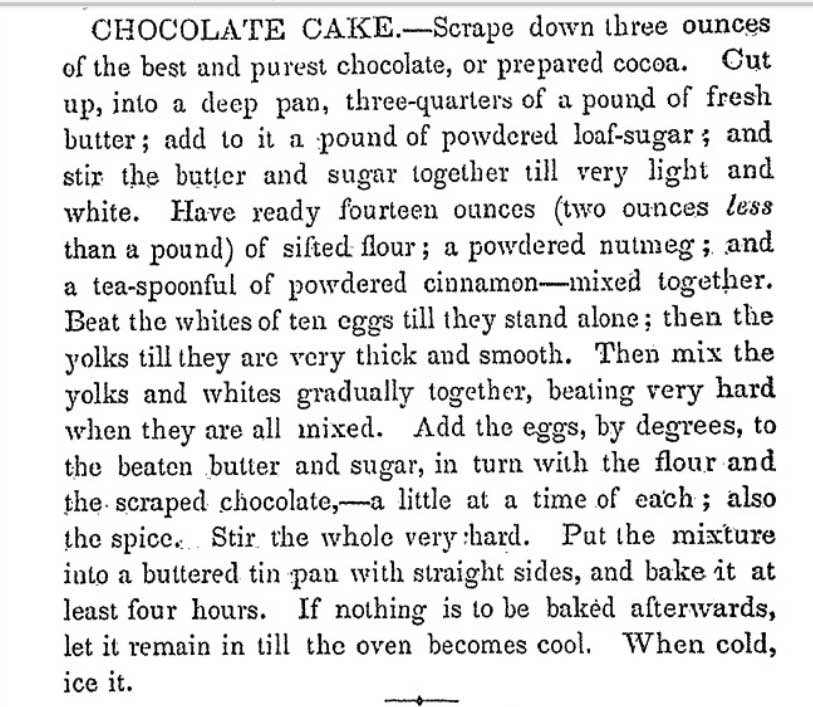

Eliza Leslie’s Chocolate Cake

Leslie’s 1846 Lady’s Receipt Book (of which there were many subsequent editions) contains what might well be the first American chocolate cake recipe.

“While chocolate had been used in baking in Europe as far back as the 1600s, Leslie’s recipe was probably obtained from a professional chef or pastry cook in Philadelphia. The recipe, which featured grated chocolate and a whole grated nutmeg, is quite different from most of today’s chocolate cakes, with its strong overtones of spice and earthy, rather than sweet, flavors.” (See Literature section at end for recipe.) [43]Karp, Liz Susman. Eliza Leslie: The Most Influential Cookbook Writer of the 19th Century. Mental Floss. 22 March 2019. Accessed August 2019.

Chocolate Cake. In: Leslie, Eliza. The Lady’s Receipt Book. Philadelphia, PA: Carey and Hart. 1847 edition. Page 201.

“CHOCOLATE CAKE.—Scrape down three ounces of the best and purest chocolate, or prepared cocoa. Cut up, into a deep pan, three-quarters of a pound of fresh butter; add to it a pound of powdered loaf-sugar; and stir the butter and sugar together till very light and white. Have ready 14 ounces (two ounces less than a pound) of sifted flour; a powdered nutmeg; and a tea-spoonful of powdered cinnamon—mixed together. Beat the whites of ten eggs till they stand alone; then the yolks till they are very thick and smooth. Then mix the yolks and whites gradually together, beating very hard when they are all mixed. Add the eggs, by degrees, to the beaten butter and sugar, in turn with the flour and the scraped chocolate,—a little at a time of each; also the spice. Stir the whole very hard. Put the mixture into a buttered tin pan with straight sides, and bake it at least four hours. If nothing is to be baked afterwards, let it remain in till the oven becomes cool. When cold, ice it.” — Leslie, Eliza. The Lady’s Receipt Book. Philadelphia, PA: Carey and Hart. 1847. Page 201.

Videos

Further reading

Haven, Alice B. Personal Reminiscences of Miss Eliza Leslie. Godey’s Lady’s Book 56. 1858. Page 344.

References

| ↑1 | Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. 1851. In: The Female Prose Writers of America: With Portraits, Biographical Notices, and Specimens of their Writings. Accessed August 2019. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 512. |

| ↑3 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. In: The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. University of Pennsylvania Press. Vol. 74, No. 4 (Oct., 1950), pp. 512-527. |

| ↑4 | Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. |

| ↑5 | Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. |

| ↑6 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 512. |

| ↑7 | Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. |

| ↑8 | Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. New York: Oxford University Press. 2004. Page 255. |

| ↑9 | Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. |

| ↑10 | Appletons’ Cyclopædia of American Biography. Eliza Leslie. Accessed August 2019. |

| ↑11 | Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Page 255. |

| ↑12 | Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. |

| ↑13 | Leslie, Eliza. Seventy five Receipts for Pastry, Cakes, and Sweetmeats. Boston: Munroe and Francis, 1828. |

| ↑14 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 519. |

| ↑15 | Longone, Jan. From the Kitchen. In: The American Magazine and Historical Chronicle. Vol. 4, No. 2. Autumn-Winter 1988-89. Page 48, 49. |

| ↑16 | Reber, Patricia Bixler. Mrs. Goodfellow – raves from Miss Leslie and others. Researching Food History blog. 6 July 2015. Accessed August 2019. |

| ↑17 | Longone, Jan. From the Kitchen. Page 48. |

| ↑18 | Ibid., Page 49. |

| ↑19 | Ibid., page 49. |

| ↑20 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 525. |

| ↑21 | Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. |

| ↑22 | Leslie, Eliza. Autobiography. |

| ↑23 | Longone, Jan. From the Kitchen. Page 52. |

| ↑24 | Rachman, Anne-Marie. Leslie, Eliza, 1787-1858. Michigan State University Library Digital Repository. Accessed August 2019. |

| ↑25 | Smith, Andrew F.. Oxford Companion to American Food and Drink. Page 255. |

| ↑26 | Karp, Liz Susman. Eliza Leslie. |

| ↑27 | Karp, Liz Susman. Eliza Leslie. |

| ↑28 | The Unites States Hotel opened in 1826 on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia. It was operated first by John Rea, and then by his son, Thomas C. Rea, who died in 1846. It was demolished in 1856, and a Bank of Pennsylvania erected in its place. Src: World Digital Library, accessed August 2019 at https://www.wdl.org/en/item/9417/ |

| ↑29 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 518. |

| ↑30 | Haven, Alice B. “Personal Reminiscences of Miss Eliza Leslie.” Godey’s Lady’s Book 56. 1858. Page 346. |

| ↑31 | Rachman, Anne-Marie. Leslie, Eliza, 1787-1858. |

| ↑32 | Madden, Etta M. Selections from Eliza Leslie. footnotes, page, 286. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. 2011. |

| ↑33 | Haven, Alice B. Personal Reminiscences of Miss Eliza Leslie. Page 346. |

| ↑34 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 526. |

| ↑35 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 526. |

| ↑36 | Smith, Ophia. D. Charles and Eliza Leslie. Page 525. |

| ↑37 | Haven, Alice B. Personal Reminiscences of Miss Eliza Leslie. Page 349. |

| ↑38 | Simpson, Henry. Eliza Leslie. In: The Lives of Eminent Philadelphians, Now Deceased. Philadelphia: William Brotherhead. 1859. Page 650. |

| ↑39 | Hines, Mary Anne, et al. Eliza Leslie. In: The Larder Invaded. Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Philadelphia. 1987. Page 67. |

| ↑40 | Savannah Morning News. Friday, 8 January 1858. Page 3, Col. 4. |

| ↑41 | Eliza Leslie. Find A Grave. Accessed August 2019 at https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/90396086/eliza-leslie. |

| ↑42 | University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia Area Archival Research Portal (PAARP). Accessed August 2019 at http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/pacscl/index.html |

| ↑43 | Karp, Liz Susman. Eliza Leslie: The Most Influential Cookbook Writer of the 19th Century. Mental Floss. 22 March 2019. Accessed August 2019. |