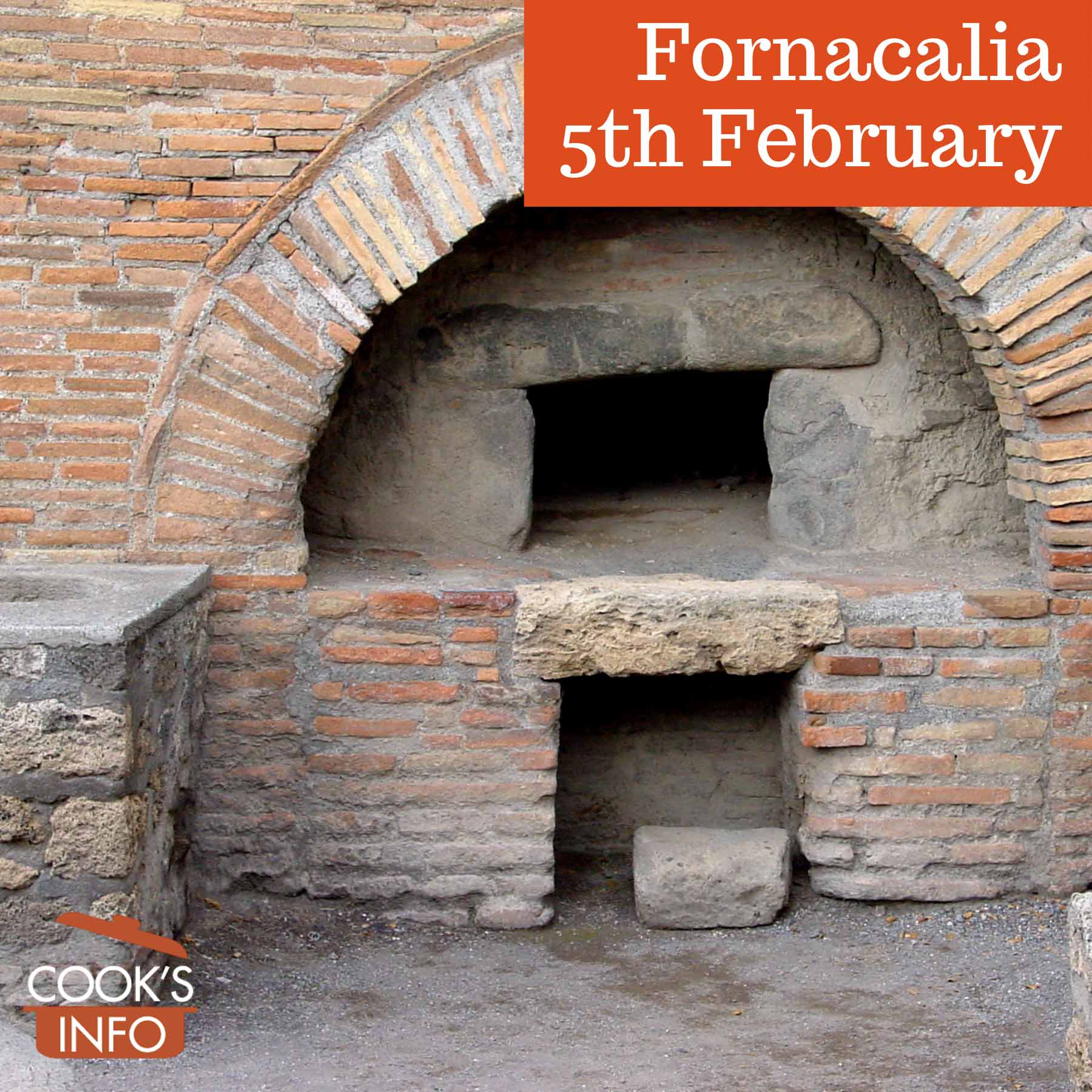

Roman oven. Camster2 / wikimedia / 2007 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The Fornacalia was a Roman festival which started on or around the 5th of February (see “Dates” below).

It was held in honour of Fornax, the goddess of grain-drying kilns that were known as fornaces (“ovens”, plural of fornax).

Your household would bring an offering of emmer wheat (“far” in Latin) to be roasted in a local community oven.

In Rome, many of the clans corresponded roughly with geographic wards of the city, which would have their own gathering halls for the ward, so the roasting may have happened at those halls. [1]Donahue, John F. “Toward a Typology of Roman Public Feasting.” The American Journal of Philology, vol. 124, no. 3, 2003, pp. 423–441. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1562137. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021.

Emmer was specifically used because it was an ancient grain with heritage significance [2]”Was dieses im Bewusstsein der Römer vor anderen Feld früchten auszeichnete, war einerseits seine symbolische Bedeutung als Urge treide und andererseits seine rituelle Verwendung” — Baudy, Dorothea. “«Der Dumme Teil Des Volks» (Ov., Fast. 2,531): Zur Beziehung Zwischen Quirinalia, Fornacalia Und Stultorum Feriae.” Museum Helveticum, vol. 58, no. 1, 2001, pp. 32–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24822426. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021. , and it was therefore the grain that was used in making “salted flour” (mola salsa) which was used ceremonially in all animal sacrifices that took place later in the year to other gods.

Roasting emmer was not just a taste preference. Previous generations had discovered that roasting it made it easier to husk. Learning how an oven made emmer more usable was an agricultural achievement. [3]”Erst nachdem die Bauern Fornax zur Göttin gemacht und die Fornacalia institutionalisiert hatten, konnten sie sich über ihren Ertrag freuen. Es geht zum einen um eine menschheitsgeschichtlich bei deutsame kulturelle Errungenschaft, denn die Technik des Getreideröstens bil det die Voraussetzung für das erste «zivilisierte» Grundnahrungsmittel puls (dem später das feinere Brot folgen sollte)” — Baudy, Dorothea. “«Der Dumme Teil Des Volks» (Ov., Fast. 2,531): Zur Beziehung Zwischen Quirinalia, Fornacalia Und Stultorum Feriae.” Museum Helveticum, vol. 58, no. 1, 2001, pp. 32–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24822426. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021.

The goddess Fornax would be supplicated to help with a safe, successful roasting of emmer grain:

“Taught by experience they toasted the [emmer] on the fire, and many losses they incurred through their own fault. For at one time they would sweep up the black ashes instead of [emmer], and at another time the fire caught the huts themselves. So they made the oven into a goddess of that name (Fornax); delighted with her, the farmers prayed that she would temper the heat to the corn committed to her charge.” [4]Ovid. Fasti 2. [512] Translated by Frazer, James George. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931.

On the Fornacalia, the offerings of emmer would be roasted, then milled. Some would be made up into cakes for eating; some seems to have possibly been delivered to the Vestal virgins for salting to make into the salted flour to be used ceremonially in future sacrifices. The vestals would begin distributing that salted flour to people starting on the 15th of February, the Lupercalia, to use with sacrifices during that festival.

#Fornacalia

See also: Roman Food, Roman Holidays

Debating the date of Fornacalia

Some people say the Fornacalia could have been on the 7th of February, but it seems possible that the 5th of February is probably the more likely of the two for the festival period to start, at any rate.

It’s believed by some scholars that the Fornacalia probably started on what the Romans called the nones of February. The nones of February was the 5th. [5] (https://www.thoughtco.com/roman-calendar-terminology-111519

Some people feel that the Fornacalia should be thought of as a period, rather than a day, and that the festival period probably started first on the 5th, with a grain roasting ceremony being held at a large temple for the overall state of Rome, and then on different subsequent days with smaller emmer roasting ceremonies being held by the various clans (curiae) of Rome in their parts of the city. The period of time argument would appear to make make some sense. But still, the starting date for it is debated, and in fact it may have varied from year to year:

“At the present day the Prime Warden (Curio Maximus) proclaims in a set form of words the time for holding the Feast of Ovens (Fornacalia), and he celebrates the rites at no fixed date; and round about the Forum hang many tablets, on which every ward has its own particular mark.” [6]Ovid. Fasti 2. [512] Translated by Frazer, James George. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931.

At the close of the period, on the 17th of February, according to Ovid, a general offering was made that covered those who didn’t belong to a clan or didn’t know what clan they belonged to. The one on the 17 of February was called the “stultorum feriae” (fools’ festival) according to Ovid because those too stupid to know their curiae [clans] celebrated then, instead of on the proper day [for their clan].” [7]Phillips, C. Robert. Fornacalia. Oxford Classical Dictionary. Accessed February 2021 at https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.2705 [8]”The foolish part of the people know not which is their own ward, but hold the feast on the last day to which it can be postponed.” — Ovid. Fasti 2. [512] Translated by Frazer, James George. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931.

The Fornacalia happened during the broader festival period known as the Parentalia, which concluded on the 21st of February. [9]Dušanić, Slobodan, and Žarko Petković. “The flamen quirinalis at the consualia and the horseman of the lacus curtius.” Aevum, vol. 76, no. 1, 2002, pp. 63–75. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20861291. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021. Page 129

Language notes

A fornax was a furnace, oven or kiln.

Some people suggest a good translation for Fornacalia is “the feast of ovens.”

Sources

Fasciano, Domenico, and Kesner Castor. “La Trifonction Indo-Européenne à Rome.” Rivista Di Cultura Classica e Medioevale, vol. 38, no. 1, 1996, pp. 7–43. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23948736. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021.

References

| ↑1 | Donahue, John F. “Toward a Typology of Roman Public Feasting.” The American Journal of Philology, vol. 124, no. 3, 2003, pp. 423–441. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1562137. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”Was dieses im Bewusstsein der Römer vor anderen Feld früchten auszeichnete, war einerseits seine symbolische Bedeutung als Urge treide und andererseits seine rituelle Verwendung” — Baudy, Dorothea. “«Der Dumme Teil Des Volks» (Ov., Fast. 2,531): Zur Beziehung Zwischen Quirinalia, Fornacalia Und Stultorum Feriae.” Museum Helveticum, vol. 58, no. 1, 2001, pp. 32–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24822426. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021. |

| ↑3 | ”Erst nachdem die Bauern Fornax zur Göttin gemacht und die Fornacalia institutionalisiert hatten, konnten sie sich über ihren Ertrag freuen. Es geht zum einen um eine menschheitsgeschichtlich bei deutsame kulturelle Errungenschaft, denn die Technik des Getreideröstens bil det die Voraussetzung für das erste «zivilisierte» Grundnahrungsmittel puls (dem später das feinere Brot folgen sollte)” — Baudy, Dorothea. “«Der Dumme Teil Des Volks» (Ov., Fast. 2,531): Zur Beziehung Zwischen Quirinalia, Fornacalia Und Stultorum Feriae.” Museum Helveticum, vol. 58, no. 1, 2001, pp. 32–39. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24822426. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021. |

| ↑4 | Ovid. Fasti 2. [512] Translated by Frazer, James George. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. |

| ↑5 | (https://www.thoughtco.com/roman-calendar-terminology-111519 |

| ↑6 | Ovid. Fasti 2. [512] Translated by Frazer, James George. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. |

| ↑7 | Phillips, C. Robert. Fornacalia. Oxford Classical Dictionary. Accessed February 2021 at https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.2705 |

| ↑8 | ”The foolish part of the people know not which is their own ward, but hold the feast on the last day to which it can be postponed.” — Ovid. Fasti 2. [512] Translated by Frazer, James George. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. |

| ↑9 | Dušanić, Slobodan, and Žarko Petković. “The flamen quirinalis at the consualia and the horseman of the lacus curtius.” Aevum, vol. 76, no. 1, 2002, pp. 63–75. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20861291. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021. Page 129 |