Opening of the Roman Market in Braga, Portugal. Joseolgon / wikimedia / 2010 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The Romans were far more generous with holidays than we are. Many of the Roman holidays involved food or agriculture.

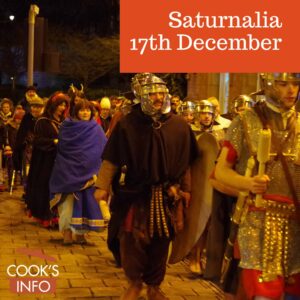

Roman holidays typically were daytime affairs, though there were exceptions such as Saturnalia which went into the night. [1]Saturnalia. In: Michels, Agnes K. “Roman Festivals: October—December.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 68, no. 1, American Classical League, 1990, pp. 10–11, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43919166. And some, such as Saturnalia, came to have seasonal markets associated with them selling goods appropriate for the holiday.

This listing of Roman holidays involving food or agriculture is not meant to be comprehensive.

See also: Roman Food, Food Holidays: Where Are They All Coming From?

- 1 Birthday of Rome

- 2 Cerealia

- 3 Consualia

- 4 Floralia

- 5 Fontinalia

- 6 Fornacalia

- 7 Idus Februarias

- 8 Ieiunium Cereris

- 9 Juternalia

- 10 Meditrinalia

- 11 Saturnalia

- 12 Terminalia

- 13 Vinalia rustica

- 14 Vinalia urbana

- 15 Roman holidays were plentiful

- 16 Fixed versus floating holidays

- 17 The holidays often blended religion with trade and business

- 18 Roman holidays typically involved feasting rather than fasting

- 19 Who exactly in the Roman world got holidays as work-free days?

- 20 Did Roman slaves get holidays?

- 21 Traces of Roman holidays survive today

- 22 Sources of information about Roman holidays

- 23 Ovid’s Fasti

- 24 Resources

Birthday of Rome

Fontinalia

Fornacalia

Idus Februarias

Ieiunium Cereris

Juternalia

Meditrinalia

Saturnalia

Terminalia

Vinalia rustica

Vinalia urbana

Roman holidays were plentiful

Some people note that Romans seem to have had a heck of a lot more official holidays than we did: some estimates put all the days, major and minor, as high as 170. But it’s important to note that some of these overlapped, [2]K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses, 54:1, 112, DOI: 10.1080/00397677908590731 , and there was no concept of two weeks annual vacation, or of even a weekend, let alone a weekend off work for that matter, then. (We moderns get approximately 104 weekend days in a year.) So, what time off Romans did get was provided by the holidays scattered intermittently but regularly throughout the year. “Because the ancient Romans did not observe a “weekend” as moderns do, these festivals would have constituted the days of rest for the populace.” [3]Roman festivals. Accessed December 2021 at https://www.unrv.com/culture/roman-festivals.php

Fixed versus floating holidays

Many of the holidays had fixed dates (called “feriae stativae“), but some (called “feriae conceptivae“) had their dates proclaimed each year by public priests, [4]”The dates of some festivals, called feriae conceptivae, are not fixed, but are proclaimed each year at the proper season, as Thanksgiving used to be.” — Michels, Agnes K. “Roman Festivals: January—March.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 68, no. 2, American Classical League, Winter 1990-1991, Page 44, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43936713. and the dates of those could change. Some holidays were rural only; some were urban only.

The holidays often blended religion with trade and business

The holidays blended both sacred and secular together, with perhaps the secular aspect to a holiday becoming more dominant over time and the religious aspect just more of a nod, as it does in many holidays in other cultures.

Many of the holidays remind us of the pastoral, agricultural origins of Rome, and involve minor gods or goddesses involved with one or two aspects of food production, or processing, or storage (such as Consualia), or even just boundaries between neighbouring farms (such as Terminalia). Several celebrated the availability of public water, and several unsurprisingly celebrated wine production. Some celebrated the trades of those involved in food production, such as the Fornacalia for bakers.

Roman holidays typically involved feasting rather than fasting

Roman holidays typically involved feasting instead of fasting, and if not outright feasting, then at least some foods to be sought out and consumed as symbolically marking the holiday. Only very few Roman holidays — Hilaria and Ieiunium Cereris being examples — involved fasting or abstention from certain foods. [5]”Fasting is the temporary abstinence from all food (ἀποχὴ τροφῆς) for ritual, ascetic, and medicinal purposes. Alien to Roman religion except for the ieiunium Cereris (Livy 36. 37. 4), which was considered a Greek import, it was infrequent in Greek cult, where feasting was more central than fasting.” — Henrichs, A. “fasting.” Oxford Classical Dictionary. 07. Oxford University Press. Date of access 1 Dec. 2021, <https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-2641>

Who exactly in the Roman world got holidays as work-free days?

It is important to note that just because a day was a holiday, it didn’t mean people necessarily got it as a work-free day. Easter Monday may be a holiday in modern times, but very few people get it as a paid day off work.

Legally, for Romans, a holiday was a day in which official business could not be conducted. But that didn’t stop lower-level economic affairs or ordinary daily chores and activities from carrying on.

“Although legal and other official business could not be conducted on days marked feriae most of the free population, especially at the lower levels of society, probably went about its business much as usual.” [6]K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses, 54:1, 111-118, DOI: 10.1080/00397677908590731

So while priests and religious officials may have been busy in temples with the required sacrifices and rituals for that particular holiday, probably ordinary people as well as slaves went about their ordinary affairs on many of these days.

Did Roman slaves get holidays?

It can be surprising to learn that slaves in Roman society actually got some holidays as work-free days.

“From time to time throughout the year slaves in the Roman world were allowed holidays.” [7]K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses.

It’s hard to say exactly how many work-free holidays slaves (or ordinary free workers, for that matter) got per year in Rome exactly.

Slaves typically got time off for Matronalia on the 1st of March; Fors Fortuna (24th June), the Nemoralia in honour of the goddess Diana (13th August, a holiday for slaves alone); and during Saturnalia (17 – 23 Dec) and the Compitalia (3-5 Jan). Sometimes special contracts for slaves would stipulate more time off work. Some documents show up to 36 days per annum.

There’s a strong argument to be made that religious beliefs initially dictated a religious obligation to give slaves holidays from work, and that that’s why this custom was kept up in the Roman world century after century. It can also be argued that permitting holidays to slaves served practical purposes, such as rewarding slaves, easing any tensions, giving them time to rest at designated times, etc.

“It might be expected too that over the course of time slaves came to regard their holidays as a set of rights and not merely a form of privilege handed down to them by the master… Since holidays were provided for under the dictate of religious appeasement this must have meant that whatever their personal inclinations, masters were under a constraint to give their slaves holidays on occasion, and that these were not just acts of pure generosity. Although in origin slaves had no inherent right to holidays, by the imperial age at latest the privilege must have become a customary right which was difficult to deny in reality. From this viewpoint, it might be said that the constraint of religion sanctioned the practical usefulness of slave holidays as a release for social antagonisms.” [8]K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses.

It’s thought that slaves got the greatest amount of freedom, and time off regular duties, during Saturnalia.

Traces of Roman holidays survive today

Some people argue that some Roman festivals have survived by evolving or being absorbed into other ones, such as Saturnalia being absorbed into Christmas, and autumnal Romano-Celtic fire rituals such as Magnus Ustus becoming present-day Magosto.

Sources of information about Roman holidays

There is no one unified source of information about Roman holidays. This is not surprising, given the tremendous geographic scope and timespan — nearly 1,000 years — of the Roman Empire in the west alone.

Officially, the way the Roman bureaucrats thought of the compilation of holiday lists was not so much as to track days when you did special celebratory things or didn’t have to work, but rather, the mirror image, as tracking the days when business was allowed to be conducted. Just about every holiday was a “holyday” and tied to a major or minor deity, after all, so certain things were prohibited on many of the “holy days.” “Citizens were required to suspend business on such dates, but they were not required to attend religious ceremonies (many did so, however, as sacrificial meat was often given in such festivals).” [9]Roman festivals. Accessed December 2021 at https://www.unrv.com/culture/roman-festivals.php

The list of allowed business days was tracked in lists called “fasti“. “fastus (aka fas)” means “that which is permitted”, with “fasti” being the plural. Dies fasti (“permitted days”) were days on which conducting business was permitted, as they were not public holidays. Dies nefasti were days on which you could not conduct business. Over time, the word “fasti” organically acquired the additional expanded meaning of a list of things ordered timewise in order of occurrence.

Sometimes, the fasti lists that people compiled were proactive, setting out what would happen when. Sometimes, they were compiled after a given time period had passed, and so described what had happened in a past year, and sometimes with these types of lists special one-time events held by an Emperor such as a triumph, etc., will be worked in along with the normal recurring events.

Examples have been preserved chiselled into stone or marble, and were often mounted in places for public viewing. These are found in various degrees of repair. Some are fragments, some are quite whole. Often it depends if they were found by various materials scavengers and if so how they were reused in the following centuries.

One such particular source of fasti inscribed into stone is now known as the “Fasti Ostienses“, covering the period from 49 BC to 175 AD. This came from the sea port of Ostia on the central west coast of Italy, an incredibly important business centre.

All these various fasti lists provide bare facts: name of event, and when.

Specific events get mentioned from time to time by other writers, such as Marcus Terentius Varro, and Sextus Pompeius Festus. For instance, Varro talks about Fontinalia, the Meditrinalia, the Vinalia rustica and the Vinalia urbana. When this occurs, the writer will — if we are lucky — flesh out our knowledge about the holiday by going into some detail on it, though at other times a writer will just mention it in passing and assume that the reader knows all there is to know about it.

Ovid’s Fasti

Ovid’s Fasti is a set of six “books” written by the Roman poet Publius Ovidius Naso (43 BC — c. 17 or 18 AD), aka “Ovid” in English.

His books of “fasti” cover Roman festivals from January to June. Far more than just a bare list, Ovid’s listings provide descriptions, backgrounds and histories to the events.

It’s believed that he left off writing the series at the mid-calendar point when he was exiled from Rome to Tomis (now Constanța, Romania), and that he never returned to the subject. Some people think or like to hope that Ovid did write the final six months, and that they were lost (and therefore might surface one day.) But others dispute that, and think the evidence is that they were never written because, among other things, in exile Ovid would not have had access to the library resources he would have needed to continue the compilation. [10]Trappes-Lomax, John. “Ovid Tristia 2. 549: How Many Books of Fasti Did Ovid Write?” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 2, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 631–33, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4493455.

Resources

A list of all Roman festivals, with suggestions on how to observe them: http://www.novaroma.org/calendar/index.html

Agnes K. Michels, Roman Festivals. Four installments in The Classical Outlook, American Classical League, 1990 (Jstor. Free access via your local public library)

Fowler, W. Warde. The Roman Festivals of the Period of the Republic. New York, NY: MacMillan. 1899.

Leon, Vicky. Roman Holidays. Los Angeles, CA: Los Angeles Times. 3 September 2007.

Schilling, Robert. Roman Festivals and Their Significance. Acta Classica, vol. 7, Classical Association of South Africa, 1964, pp. 44–56, http://www.jstor.org/stable/24591223 (Free access via your local public library)

The Roman Calendar (Encylopaedia Britannica)

References

| ↑1 | Saturnalia. In: Michels, Agnes K. “Roman Festivals: October—December.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 68, no. 1, American Classical League, 1990, pp. 10–11, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43919166. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses, 54:1, 112, DOI: 10.1080/00397677908590731 |

| ↑3 | Roman festivals. Accessed December 2021 at https://www.unrv.com/culture/roman-festivals.php |

| ↑4 | ”The dates of some festivals, called feriae conceptivae, are not fixed, but are proclaimed each year at the proper season, as Thanksgiving used to be.” — Michels, Agnes K. “Roman Festivals: January—March.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 68, no. 2, American Classical League, Winter 1990-1991, Page 44, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43936713. |

| ↑5 | ”Fasting is the temporary abstinence from all food (ἀποχὴ τροφῆς) for ritual, ascetic, and medicinal purposes. Alien to Roman religion except for the ieiunium Cereris (Livy 36. 37. 4), which was considered a Greek import, it was infrequent in Greek cult, where feasting was more central than fasting.” — Henrichs, A. “fasting.” Oxford Classical Dictionary. 07. Oxford University Press. Date of access 1 Dec. 2021, <https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-2641> |

| ↑6 | K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses, 54:1, 111-118, DOI: 10.1080/00397677908590731 |

| ↑7 | K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses. |

| ↑8 | K. R. Bradley (1979) Holidays for slaves, Symbolae Osloenses. |

| ↑9 | Roman festivals. Accessed December 2021 at https://www.unrv.com/culture/roman-festivals.php |

| ↑10 | Trappes-Lomax, John. “Ovid Tristia 2. 549: How Many Books of Fasti Did Ovid Write?” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 56, no. 2, Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 631–33, http://www.jstor.org/stable/4493455. |