Klicking Karl / wikimedia / 2007 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The Goose Fair is held in Nottingham, England, every year in October.

It’s opened by the mayor of Nottingham who gets to ring silver bells to mark the opening, and lasts for 3 days.

The fair has been running for hundreds of years. Depending how you define the fair, some date it back to the 1200s.

The fair starts on random dates chosen yearly by a committee, typically towards the end of September or the beginning of October.

The fair is a very big deal; a major event in England on the carnival circuit.

Traditionally, over the centuries, it has had two aspects to it: a business side, where livestock and agricultural commodity trade is conducted, and the carnival side.

Goose fair sign. Stephen McKay / geograph.org.uk / 2007 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Over the centuries, despite its name, the fair has been particularly popular for items other than geese, commodities ranging from cheese to horses. Years when geese actually were in good supply at the fair always seemed to merit a notice from a reporter:

“Nottingham Goose Fair — The supply of geese was abundant, of good quality, and such as to keep up the propriety of the name bestowed upon our October fair.” — Nottingham Review and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties. Friday, 6 October 1837. Page 3, col 3.

Apparently roast goose for fair goers to eat was also a feature:

“The Lincoln Times of Tuesday, speaking of our annual festival, says: “Nottingham Goose Fair. This celebrated fair, as celebrated for the smell of roast geese, as for live geese visiting it, commenced yesterday.”” — Nottingham Review and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties. Friday, 6 October 1848. Page 3, col. 3.

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/NottinghamGooseFair/

Goose fair, aerial view. David Lally / geograph.org.uk / 2011 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Early History

The first written mention of the fair being referred to as “Goose Fair” appears to date from 1542, in a purchase note recorded by a John Trussell. [1]”about the purchase of a pair of trousers at the ‘Goose Fair Nottingham’, by John Trussell, a steward of the Willoughby family from Wollaton.” — Breese, Chris. Cheese riots and dragoons: The complete history of Nottingham Goose Fair. Notts TV. 3 October 2016. Accessed October 2021 at https://nottstv.com/cheese-riots-and-dragoons-the-complete-history-of-nottingham-goose-fair-2016/

The fair was not held in 1646 owing to the bubonic plague. [2]Breese, Chris. Cheese riots and dragoons: The complete history of Nottingham Goose Fair. Notts TV. 3 October 2016. Accessed October 2021 at https://nottstv.com/cheese-riots-and-dragoons-the-complete-history-of-nottingham-goose-fair-2016/

In 1811, the Goose Fair ran for 9 days:

“Fairs — September 30, Hope, Wragby — October 2, Nottingham Goose Fair (proclaimed for 9 days), Retford, Stafford, Burgh, Swineshead, Daventry — 3, Chapel-en-le-Frith, Saltfleet — 4, Heckington (Linc.) Wirksworth.” — Nottingham Journal. Saturday, 28 September 1811. Page 3, col. 2.

Goose Fair and Petty Crime

There was a great deal of thieving associated yearly with the fair. Newspaper reports on sites and sounds at the fair frequently included a running tally of the crimes committed there to date that year.

In 1825, 95 people were arrested in one night alone for pick-pocketing at the fair:

“Nottingham Goose Fair: The pickpockets were on the alert, and so were the police. In consequence of the vigilance of the latter, there were, on Tuesday morning, no less than ninety-five prisoners in the town house of correction — a number greater than was ever confined at one time in the same prison before.” — York Herald. Saturday, 8 October 1825. Page 4, col. 4.

In 1826, a writer for the Nottingham Mercury went into great detail about several petty crimes committed at the fair:

— Mr. North, cheesemonger, Middle-hill, had his pocket picked of a pocket-book, in the cheese fair, on Monday. A short time before it was abstracted, Mr. North had taken out a considerable sum of money (nearly 300 pounds), and paid it away in the fair, so that the thieves found the book empty, and lost the booty.

— Mr. Barrowcliff, the Blidworth carrier, had his pocket picked, in the fair, of a canvas purse and 14 shillings in silver.

— The overlooker of the cotton mill, at Radford, had his pocket picked, near the shows, between four and five o’clock in the afternoon, of a pocket-book and seven one pound notes of Wright’s Nottingham bank.

— About six o’clock in the evening, at the bottom of Sheep Lane, a gentleman had his pocket picked of a purse, containing two one pound notes and a shilling. A person, who saw the transaction, immediately collared the rascal, but received so severe a blow on the face, that he was compelled to quit his hold, and the fellow escaped with his prize.

— Upon information received by the police, a party of officers repaired to a spot behind the wild beast show, where they discovered a cart, attended by three men, whom they immediately apprehended. On examining the cart, it was found to be a receptacle for stolen goods of every description. It contained several tea kettles, cheeses, and pistols; two powder flasks, filled with powder; a quantity of housebreaking implements; a number of new waistcoats, and a great variety of other articles. There can be no doubt that this depository belonged to a regularly organized band. Several articles have been owned, and the parties have been remanded. One of the persons is a traveller with a swing boat, from Leicester.” — Nottingham Mercury. — In: Leicester Chronicle. Saturday, 7 October 1826. Page 3, col. 5.

In 1828, a young man was sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, first and last fortnight solitary, for stealing geese from the fair:

“James Brown, aged 21, was charged with stealing six geese and a turkey, the property of Richard Dowall, of Gotham, during the night of Turesday in the Nottingham Goose Fair week. William Towle met the prisoner about half past two in the morning, carrying a bag and a pair of wallets; he asked what he had got, and prisoner said, two or three hares; witness felt of the bag and perceived wings, and said, why you have got pheasants, too. On searching the bag, he found the poultry.” — Nottinghamshire Michaelmas Quarter Sessions. Nottingham Review and General Advertiser for the Midland Counties. Friday, 17 October 1828. Page 4, col. 2.

Business side of fair

The press frequently covered in detail the business trade being conducted at the fair, reporting on both commodity and livestock prices.

In 1778, a reporter noted the average price of cheeses being sold at the air:

“At Nottingham Goose-Fair last Week, Cheese sold in general from 28s. to 30s. per Hundred.” — Drewry’s Derby Mercury. Friday, 2 October to Friday 9 October 1778. Page 4, col. 2.

In 1826, a writer for the Nottingham Mercury wasn’t impressed by the commodities on offer at the fair:

“Nottingham Goose Fair commenced on Monday, and, both in appearance and reality, was under any fair that can be remembered by the oldest inhabitant of the town. The cheese was very good in quality, but no very liberal supply, and even this did not meet with a ready sale. During the first part of the morning, prime dairies fetched 72 shillings; but towards the afternoon prices fell to 68 shillings. Prime old cheese Sold as high as 74 shillings to 76 shillings. By the return of the toll-collector, the quantity sold is less than ever has been recollected. The cattle market was but thinly supplied, there being not more than 20 fat beast among the whole. The prices demanded in the first instance were most exorbitant, but the sale was tolerably brisk, and the sellers came down considerably in price. One person purchased two bullocks, at 12 pounds each below the sum demanded. There were a great many buyers for the London markets. Among good horses the sale was very heavy and scarcely any bidders; the inferior kind tolerably brisk; but, on the whole, business was extremely slack, when compared with former years. Tuesday’s cheese market continued very languid, notwithstanding the very great reduction in price. The largest quantity was of the Gloucestershire kind: good dairies fetched 64 shillings, and good blend milk cheese sold for 46 shillings, 48 shillings and 50 shillings. Onions, of the best quality, were two shillings sixpence, and the inferior sort varied at about two shillings.” — Nottingham Mercury. — In: Leicester Chronicle. Saturday, 7 October 1826. Page 3, col. 5

In 1829, a reporter noted the impact of rain on the prices being obtained:

“The above annual fair, which is the largest in the year, for fat stock, horses, cheese, &c., commenced on Friday, the 2nd inst., and a great falling-off in prices has been the result. The quantity of cheese pitched in the market was not so large as we have witnessed, but the quality, both plain and coloured, by no means inferior to former years. Early in the morning, the farmers discovered that buyers of large dairies were not numerous, nor disposed to purchase any thing like the price of the preceding year. Prime old cheese was sold at 54s. to 58s., and the best new did not average more than 44s., and inferior was disposed of at 36s. to 40 s. Even at this reduction the market was extremely dull throughout the whole of Friday, and on Saturday the holders were glad to sell by the single cheese, at the wholesale prices, many of them declaring, if times did not improve, and that shortly, they should be totally ruined, as sales of this description would never enable them to pay the rents of their farms. Fat stock went off heavily, at 6s. per stone; in short, there seemed to be a scarcity of money in all parts of the fair. Good horses appeared in request, and those that were sold fetched tolerable prices, particularly of the draught kind, but the inferior sort were unsaleable. The rain was almost incessant on the first day, and Saturday proved nearly as bad.” — Country Fairs: Nottingham Goose Fair. Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. Sunday, 11 October 1829. Page 4, col. 3.

Nottingham Goose Fair was one of many large fairs that happened in England annually. For the entertainers that made up the carnival side of it, it was just one stop among many during the season, and when Goose Fair wrapped up, they were immediately on the road to try their luck at the next fair in the autumn schedule:

“The mirth and festivities of Goose Fair have this year experienced a woful [sic] change, owing, in some measure, to the weather, but more particularly to a lack of the needful, without which a gloomy aspect is sure to preside. The great attraction, however, was Wombwell’s menagerie, for the upper classes, and the lower contented themselves with a peep at the Red-barn Tragedy, the Pig-face Lady, or the Learned Pig; Burke and Hare were likewise in more booths than one; and while each party bellowed incessantly to draw the browns, now and then the straggling pence dropped into their coffers. The absence of the rhine, however, prevented the exhibitors from saying that Goose Fair had not this year proved a flat concern in more ways than one. On Wednesday, the principal shows had quitted the town, some of them steering their course for Leicester Fair, which will commence to-morrow, October 12th, but with a worse prospect by far than Nottingham presented.” — Country Fairs: Nottingham Goose Fair – The Pleasure Fair. Bell’s Life in London and Sporting Chronicle. Sunday, 11 October 1829. Page 4, col. 3.

The Great Goose Fair Cheese Riot of 1766

By the 1700s, cheese became a far more important commodity at the fair than geese, despite the fair’s name. In 1766, ten years before their American cousins would riot over tea, the Goose Fair attendees of Nottingham were rioting over cheese.

“Cheeses were picked up and hurled at stall holders. This started a riot in which stalls were overturned and cheeses bowled along the ground. The mayor himself was knocked over by a flying cheese, and finally the magistrates had to call out the Dragoons…” [3]Breese, Chris. Cheese riots and dragoons: The complete history of Nottingham Goose Fair. Notts TV. 3 October 2016. Accessed October 2021 at https://nottstv.com/cheese-riots-and-dragoons-the-complete-history-of-nottingham-goose-fair-2016/

The riot first broke out on 2 October 1776, and continued for several days. Reputedly, the cause was a group of merchants from Lincolnshire buying up a great deal of the cheese on offer, with the intention of taking it away from Nottingham for sale and consumption in Lincolnshire.

Historians now identify this cheese riot as part of the 1766 food riots which swept England, peaking in September and October, in response to food prices rising dramatically in response to poor harvests that year. In Nottingham, local patriots feared that, at a time of perceived impending food shortages, outsiders were striving to deprive them of basic food-stuffs:

“Nottingham, Oct. 2. Our great annual Cheese Fair began this day; when the Factors bought considerable quantities, and, not having opportunity or time to remove the cheese, had collected it together in a heap, to be watched all night, as is customary; when the mob, offended at their buying so briskly the first day, seized all the Factors cheese, notwithstanding the most strenuous endeavours of Magistrates and Constables, who surrounded the cheese, read the Proclamation against Riots, and did every thing in power to prevent it. When it was all stolen or distributed, they left the Farmers cheese undisturbed, and all was quiet before ten at night.” — Country News. Stamford Mercury. Thursday, 9 October 1766. Page 3, col. 1.

More details were reported on a few days later:

“Our Fair, generally called Goose Fair, began Yesterday, and it being a fine Day, the Town was full of Company, and a larger Quantity of Cheese set down than has been known for some years; the Price from 24s. to 27s. per Hund. Cheshire from 32s. to 36s. Every thing was well conducted till the Evening, when from the Behaviour of some rude Lads, a Riot was apprehended: Several Persons from Lincolnshire, who had brought about Sixty Hundred of Cheese, laid it in one Heap, and were threatened they should not stir a Cheese till the Town was first served; they applied for Protection, but it was not to be had. About Seven o’Clock the Mob began to be outrageous, fell upon the Heaps of Cheese, and amidst loud Shouts, in a short Time, took and destroyed the whole Parcel, which was chiefly carried off by Women and Boys. The Riot continued all Night. Part of the Mob went to the Trent Bridges, searched all the Warehouses there, but finding no Cheese returned to the Town: in the mean Time two or three of the Party were secured and carried before the Justices, then met at the Coffee-House in Peck-Lane; this redoubled their Fury, they broke the Windows belonging to the House, tore the Pavement and threatened destruction to all who opposed them: It was thought prudent to discharge the Lads in Custody, and then they retreated. About Eleven o’Clock a Messenger was dispatched to Derby, requesting that a Party of General Elliot’s light Dragoons quartered there, might be sent to the Assistance of the Civil Power here: At Six Yesterday Morning a Party came in mounted, and were in two Hours after followed by another on Foot, since which we were very peaceable, till Seven o’Clock last night, when a Riot more dangerous than the former broke out; for the Mob pressed so hard upon the Soldiers, who were upon Guard at the New Change, that they were obliged to fire upon them, and many Shot were exchanged, but the Rioters were soon dispersed in the Town; however a Party went along to the Trent-Bridge, where it is said, they seized a Boat laden with Cheese. Much Mischief has been done, but the Particulars could not be collected in Time for this Paper, before it went to the Press.” — Country News from the Nottingham Journal. Derby Mercury. Friday, 10 October 1766. Page 2, col. 2.

Further reading on the cheese riot

Charlesworth, Andrew, and Adrian J. Randall. “Morals, Markets and the English Crowd in 1766.” Past & Present, no. 114, [Oxford University Press, The Past and Present Society], 1987, pp. 200–13, http://www.jstor.org/stable/650966.

Shelton, Walter J. “The Role of Local Authorities in the Provincial Hunger Riots of 1766.” Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, vol. 5, no. 1, The North American Conference on British Studies, 1973, pp. 50–66, https://doi.org/10.2307/4048357.

Yarnspinner, Valentine. Nottingham Rising – The Great Cheese Riot of 1766 & the 1831 Reform Riots.

The Goose Fair During World War One (1914-1919)

The Goose Fair was held in full in 1914 despite World War One which had started on 28 July 1914:

“By a majority, of a vote, of 23 to 17, the Nottingham City Council, at a specially summoned meeting, yesterday, decided that the Goose Fair, which is famous throughout the country, shall be held as usual.

Had it not been for the representation of various prominent citizens, that the carnival should be suspended under the unparalleled circumstances, because they believed it would be an insult to the dead, a cruelty to the sorrowing, and an offence to the best thinking people in the city, the meeting would never have been called. Even as it was, the Town Clerk explained that the Goose Fair was a chartered fair, which had existed for many centuries, and in the charters there is nothing to enable the Corporation to suspend it for one year. In his opinion, the people to whom spaces had been allotted would be in the position to sue for damages for breach of contract.

The decision of the Council was further influenced by an address from the Rev. T. Horne, chaplain to the Showmen’s Guild, who reminded the members that there were 73,000 people directly concerned in maintaining the itinerant amusements of the fairs, and that the public did not want to be continually dwelling upon the horrors of war.” — Nottingham Goose Fair. Sheffield Daily Telegraph. Thursday, 10 September 1914. Page 10, col. 5.

In 1915, however, the carnival aspect of the fair was discontinued, but the business side of the fair, which was the trade in livestock, was allowed to go ahead:

“Breaking a continuity of custom extending over several centuries, Nottingham Council yesterday resolved not to allow the holding this year of the annual Goose Fair, except for purely business purposes relating to the sale of stock. The amusements side of the fair, to which the market-place has always hitherto been given over for three days, has been entirely stopped in consequence of the war.” — Nottingham Goose Fair. Birmingham Daily Post – Tuesday 20 July 1915. Page 9, col. 4

The main reason for the discontinuation of the carnival side was that as there could be no evening lighting, there could be no midway or rides, which had come to be the main feature of the fair:

“At their meeting, yesterday, the Nottingham City Council unanimously decided not to hold the historic Goose Fair this year, or, in fact, to permit any of the pleasure fairs usually held at Easter, Whitsuntide, and October during the duration of the war. There has always been an agitation from certain interested quarters against the Goose Fair in October, but the things that weighed in with the Markets and Fairs Committee in supporting the recommendation was that there could be no lighting in the evening, and therefore the Showmen’s Guild said it would be no use their coming.” — No Nottingham Goose Fair. Sheffield Daily Telegraph – Tuesday 20 July 1915. Page 5, col. 2.

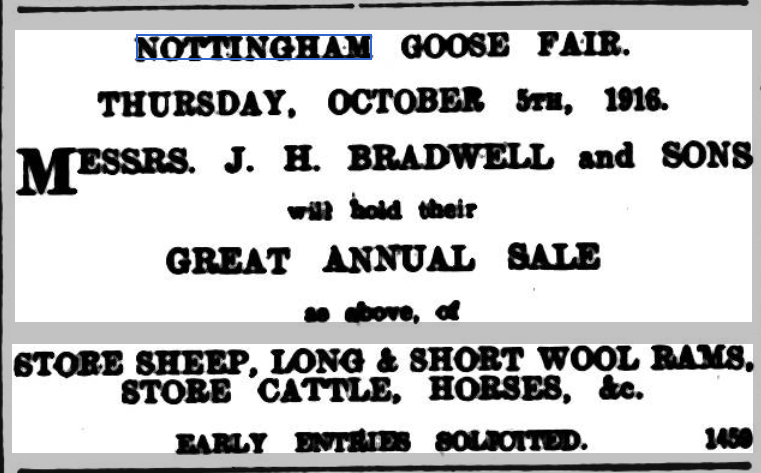

Here’s an advertisement for the sale of livestock at the fair in 1916:

Nottingham Journal – Saturday 23 September 1916. Page 6, col. 2.

The Goose Fair continued to be held yearly for livestock sale only, until 1919.

The Goose Fair recommenced full operations again including the carnival on the 2nd of October, 1919. The following piece implies that there may have been some pressure on morality grounds to keep the fair going only as a livestock trade show, by keeping the wartime Council resolution disallowing the carnival part. But, in the event, the carnival part was allowed to begin again:

“To the accompaniment of a clang of bells, a hooting of sirens, and the mingled music of many organs, Nottingham at midday yesterday gave itself up to the delights and diversions of its Victory Goose Fair.

A few minutes after the hour had chimed from the Exchange clock, the Mayor, the Sheriff, the Under-Sheriff, and the Town Clerk, in civic robes and chains of office, preceded by the Macebearer and attended by a number of members of the Corporaton, mounted a platform at the Marketplace end of Smith-row to bestow on the Fair the municipal benediction. A dense crowd surged round the platform, and in front of the Exchange and along the expanse of Long-row thousands of citizens had gathered to witness the revival of the old custom — which had passed unobserved for more than twenty years — of proclaiming the Fair.

Horses, gondolas, and motor-cars were abruptly pulled up, and organs and bells were stilled as the Town Clerk began to read the proclamation, which lays down that the Fair shall be held at Nottingham for ever. The reading finished, the Mayor briefly enjoined the populace to enjoy the fun of the fair to the full, to preserve good humor, and to refrain from disorder. As the civic party turned to leave the platform, organs broke again into melody, roundabouts resumed their journeys, bells clanged in every quarter of the Great Market-place, and Goose Fair had definitely begun.

In the Exchange Hall the chief magistrate and the others doffed their robes and then proceeded to make a tour of the fair. As time was pressing, only one show was actually visited, and that was the fine menagerie of Messrs. Bostock and Wombwell, near the Queen Victoria statue. From here the party passed along Beastmarket-hill and South-parade (inspecting the various roundabouts and shows on their way), and so returned to the Exchange for the luncheon, given by the chairman of the Markets and Fairs Committee Mr. J. H. Freckingham) and the vice chairman (Mr. A. Cullen).

Here, in the course of the meal, was partaken of the only goose that was seen or heard of in connection with the opening of the fair. It was a happy choice of a joint, and the brandysnap which made its appearance with the cheese served still further to accentuate the special purpose of the lunch, which was to celebrate the revival of the fair after its wartime lapse.

The mayor (Alderman J. E. Pendleton) proposed the health of the chairman and vice-chairman of the Markets and Fairs Committee, and Mr. Freckingham, in reply, said in all probability the receipts from Goose Fair this year would be the best on record. They would probably reach 2,000 pounds, compared with 1,700 pounds in 1914, and 953 pounds in 1890.

The speaker went on to foreshadow the possibility of the committee’s having to secure another square near at hand for market purposes. It would be disastrous to businessman in the centre of the city to take the square far away, and the committee had an admirable site in view which he thought would meet all requirements. At the same time, he felt the time was not yet right for the change. The committee’s receipts this year would reach 13,000 pounds — (applause) — and they would have 6,000 pounds to hand over to the Finance Committee.Referring to the Cattle Market, Mr. Freckingham said they were going to make it the leading fat and general stock market in the Midland counties. He was of opinion that they would soon need materially to enlarge it. They had allotted stands to the Leicestershire Farmers’ Society, and it was believed that the Nottinghamshire Society would follow suit.

Mr. P. Collins, the well-known showman, who is a town counsellor of Walsall, this year‘s president of the Showmen‘s Guild, and who, with Mr. W. Savage (secretary of the Guild) was the guest of the committee, gave the toast of the Mayor and Corporation of Nottingham.

“We showmen,“ he said, “consider that Nottingham Goose Fair is the best fair in England today, and we were never more delighted than when the Council rescinded the resolution vetoing the carnival.“ He went on to say that he represented 70,000 showmen and showpeople (with at least 6,000,000 pounds invested in the industry) “and“, he added, “if you had not held a fair this year, your decision would have been emulated throughout the land.“

Mr. Collin‘s further declared that there was nothing immoral about the fair. In this regard the showmen‘s livelihood was at stake, and they could be trusted to see that no doubtful or indecent side-shows made their appearance. (Applause.)

The health of the Sheriff (Mr. J Morris) was proposed by Alderman E. Huntsman in the happiest of speeches, and after the Sheriff had replied, Mr. J. Bowles made a short speech thanking Mr. Freckingham and Mr. Cullen for the hospitality.

During the afternoon and evening dense crowds thronged the Marketplace, although, by reason of the strike, the number of people coming in from the surrounding districts was considerably less than in pre-war times.

At the same time, there was no diminution in the fervour for merry-making, and all ages and classes did their best to make this, the first day of the Peace Goose Fair, a day of jubilation and rejoicing after the stress and sorrow of four years of war.” — The Best Fair in England: Animated Scenes Attend the Revival of the City’s Famous Carnival. Nottingham Journal. Friday, 3 October 1919. Page 3, col. 2.

Another newspaper put opening day attendance in 1919 at 60,000 people:

“At the opening of Nottingham Goose Fair to-day, the ancient proclamation was read before the Mayor and the Corporation in the presence of 60,000 spectators.” — Globe. Thursday, 2 October 1919. Page 6, col. 5.

The Goose Fair moves to new enlarged grounds (1928)

For the first 700 years of its history, the fair was held in the Old Market Square.

On the 4th of October 1928, it was moved from there to its current location which is the Forest Recreation Ground because it outgrew the market square:

“Nottingham Goose Fair, a three day’s carnival begins to-day… Goose Fair was held in Saxon and Norman times and a charter of King Edward I in 1284 enjoins that the burgesses of the ancient town of Nottingham ‘shall have a Fair on the even of the day and the morrow of the Feast of St. Edmund, King and martyr, and for twelve days following thereon.’ With all the ancient ceremonial the Fair was declared open by the Lord Mayor in the presence of a large crowd. Moved for the first time from the Market Place, the shows and stalls have been erected at Nottingham Forest, an open space with no such limitations as exist in the centre of the big city, and it seems likely that Hull will lost its distinction of staging the biggest English fair.” — Goose Fair But No Geese. Leicester Evening Mail – Thursday 04 October 1928. Page 10, col. 5.”

The Goose Fair in 1935:

The Goose Fair During World War Two (1939-1945)

As in World War One, though the carnival side of the fair was cancelled, the livestock trading component was allowed to carry on. The only difference was that whereas in World War One the carnival aspect was allowed for the first year of the war, in World War Two the livestock-only aspect of the fair was implemented right at the very start.

“One of the popular attractions which thousands of people living far beyond the boundaries of the city and county will miss this year is the Nottingham Goose Fair. The war has compelled the Markets and Fairs Committee to cancel it. “All the spaces in the forest were allocated just before the outbreak of hostilities, but owing to the grave international situation at the time,“ stated Mr. C. G. A. Austin, clerk to the markets, “we did not send out letters to the various showmen. With the country at war it is impossible to hold Goose Fair this year.“ A suggestion had been made that, with the extension of Summer Time, it might have been possible for the fair to operate during the hours of daylight only. Even if the showmen were willing, however, to go to the city, many of them have had their powerful engines which draw the vans commandeered for military purposes and they are left with no methods of haulage. The closing down of the fair will mean a loss to the city rates of about 4,000 pounds.

It is of interest to note that the chairman of the Nottingham Markets and Fairs Committee, Alderman J. H. Freckingham, is a native of Abb Kettleby, near Melton, and he was apprenticed to an iron monger at Oakham. During its long history, the Goose Fair has been cancelled on very few occasions. That was of course, the period during the great war, 1915-1919. In 1646 it was not held because plague was rife, and in 1752 it was given a miss owing to a change in the calendar, 11 days being dropped out of it in September. The citizens had their fair as usual in the following year and the ancient observance still has such astonishing vitality that the cancellation of next month’s event must be regarded as another interruption, not the termination of the show that has had one of the world’s longest runs.” — Sidelights from Many Quarters: No Goose Fair. Grantham Journal. Saturday, 30 September 1939. Page 5, col. 3.

It made the news that geese, long absent from the Goose Fair, actually made an appearance in 1939.

Geese at the Nottingham Goose Fair, 1939. Nottingham Evening Post. Thursday, 5 October 1939, Page 1, col. 2.

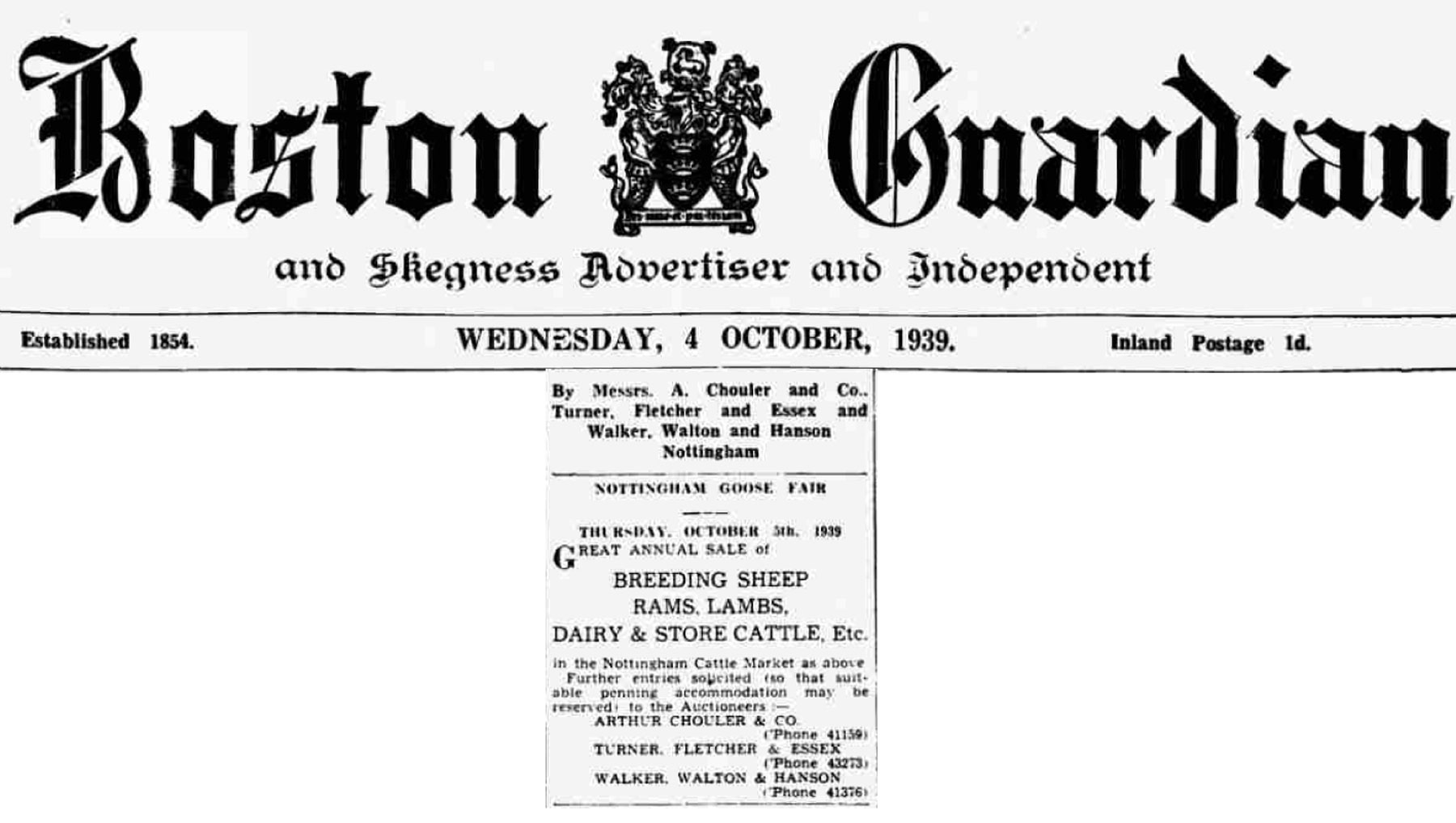

More substantial livestock trading took place as well in 1939.

Boston Guardian – Wednesday 4 October 1939. Page 1, col. 5.

In 1940, the business of the fair continued, but again with no attached carnival:

“Although Nottingham Goose Fair for the second year in succession had been shorn of its trappings as a carnival of fun, the centuries-old purpose for which it originated still flourished at the Cattle Market today.

True, the numbers of cattle and sheep for sale were down generally on last year, but the effect was not entirely due to the war. There were a variety of reasons.

These included the difficulty of transport, which to some extent affected the attendance of dealers at the market, and the unusually dry season and consequent difficulty of obtaining feeding stuffs.

Another factor was the concentration of war time arable farming.

No goose present

Last year half a dozen geese maintained the tradition, but this morning not a single goose was penned.

Two or three horses were on offer. Sheep and lambs totalled about 5,000, as compared with 6,000, last year. Irish cattle numbered about 80, as against 250, and store cattle and dairy cows, which were about the same, included 64 dairy cows from Mrs. J. R. Collington’s model farm at West Bridgford.

Prominent breeders, including Lord Glanely, Mr. Stuart Paul, of Ipswich, Lady Watson, the Earl of Ellesmere and Major V. S. Bland, of Aldbourne, Wilts., sent a total of 67 pedigree ram lambs.

This year a root show and sale in aid of the Red Cross was arranged by Messrs. Stewart and Brewill, and some exceptionally fine turnips, cauliflowers and kale were on view.” — Nottingham Goose Fair, Shorn of Carnival Trappings, Cattle Market Sales as Usual. Nottingham Evening Pos. Thursday, 3 October 1940. Page 5, col. 2.

Livestock trade only at the fair continued for the remaining years of World War Two.

World War Two ended on 2 September 1945. When the Goose Fair opened on the 4th of October 1945 for its first post WW2 occurrence, the carnival aspect of the fair was allowed to swing back into operation:

“Nottingham Goose Fair, the annual carnival which has been a notable feature of the city’s life during more than six centuries, was opened to-day on the Forest. It is the first to be held on a full scale since before the war.

As the hour of noon chimed from Little John, the Lord Mayor, with Alderman J. H. Freckingham, chairman of the Markets and Fairs Committee, the Sheriff, the Town Clerk and other Council officials, set the three-day fair in motion.

This was done in the time–honoured way by the Town Clerk reading the Charter and the Lord Mayor ringing the massive bronze bells, borrowed from one of the fair’s amusement sections.

“It’s a proper Goose Fair morning.“ How often this phrase is heard on the buses and in the streets when the first foggy mornings of the autumn appear! It was certainly real Goose Fair weather today.

The thousands of people contemplating a visit to the first great autumn carnival for seven years need have little fear of inclement weather, with the barometer standing as high as it is at present.

Although it slid back a few points during the night, it is still in the region of fine weather, and the Air Ministry’s forecast was for a warm sunny day.

It is expected to be chilly tonight, so it is as well for those who intend staying out late to be warned.Nottingham‘s ancient carnival is the Mecca to which thousands of people of all ages make a pilgrimage from a wide area.

Goose Fair seems to have something for people of all ages.

For the youngsters the roundabouts are the main attraction, for the young grown-ups there are the trials of strength and skill, whilst for those of a speculative turn of mind there are the glittering stalls, where fancy prizes become one’s property at a turn of a wheel.

On the laden buses homeward bound from the fair one sees people hugging gigantic toys and other articles, and there is usually much good-humoured banter.

On one occasion a standing passenger on a crowded city bus held up a biscuit barrel for general inspection.

“My, that will look nice on the sideboard,“ said the conductor.

“We haven’t got a sideboard,“ retorted the proud owner of the barrel.

“Oh, I’ll come and draw you one” replied the conductor, as quick as a flash, and joined in the shout of laughter which followed.

The railways are making preparations for a big influx, and on Saturday the L.M.S. are running specials from Derby, Mansfield, Lincoln, and Chesterfield. As Derby County are playing Nottingham Forest there will be a mass of their supporters, who will also visit the fair before returning.

Although the L.N.E.R. are not running any special excursions, all local trains will be strengthened to the limit to cope with the expected rush.

“We anticipate being very busy indeed,” said a railway official to the “Post” today.

Alderman Freckingham, speaking at the opening ceremony, said it was a great joy to have their old-fashioned Goose Fair once again. “I first opened the fair in 1914, in the Old Market Square, and it was a wonderful, rollicking good fair. I want this to be the same,“ he added.

The Lord Mayor said that a fair similar to Goose Fair had been in existence in the city for 1,000 years, although it was not until 1581 that the term Goose Fair was used, and which was believed to have arisen from the sale of geese. There might be some question whether it was actually the biggest fair in the country, but there was a little doubt that it was one of the most famous.

Counselor Carney recalled that the only times Goose Fair had been interrupted were during the two European wars, during the calendar revision of 1752, and during the plague, in the 17th century.

One of those attending the opening was Mr. G. C. A. Austin, former clerk of the markets, who has been responsible for the layout of many fairs, and has attended over 40 opening ceremonies. The only times he has missed were during the two world wars, and once when he was ill.

There were over 5,000 people at the opening. Every avenue was packed, people were standing at the top of the helter-skelter and some of the workmen stood on the top of their roundabouts.

A “Post“ representative accompanied the Lord and Lady Mayoress, and the Sheriff and Mrs. Blandy on their official tour of the fair. Immediately after the opening ceremony the Lord Mayor went to the St. John Ambulance Brigade headquarters to disrobe, after which he entered with zest into the spirit of the occasion.

The Monte Carlo Rally ride was the first thing to catch his eye, and to the strains of “Come into the kitchen with Dinah“, and before a cheering crowd, he set the ball rolling by careering round the circuit with Alderman Freckingham as his car passenger. Several times he came into collision with the roadster driven by the Sheriff, who was accompanied by the Lady Mayoress.

The next stop was at John Proctor’s mammoth zoo, and here the Lord Mayor was shown a 10-week-old lion cub, a daughter of the untamable Jubilee. The club did not seem to appreciate the importance of her visitors, and did her best to elude the caresses showered on her.

No more pleased was Minnie, an eight-year-old bear, which was taken on to the rostrum at the entrance to the booth to greet her visitors. Neither an apple nor the traditional bottle of milk could persuade her to face the whirring newsreel camera.

She made a wild lurch for the booth entrance, dragging her keeper with her, much to the delight of the crowd. She soon reappeared, however, and this time she relented a little after the Lord Mayor had helped the keeper to stop her plunging into the large audience.

A visit to the living Pixie afforded the Lord and Lady Mayoress an opportunity of a talk to the world’s smallest man, but they were unable to take advantage of his hospitality to the extent of sitting down or even entering his home, as chairs and house were hardly bigger than those in a doll’s house.

Trying his hand at rifle shooting, the Lord Mayor anxiously inquired about the glassware underneath the diminutive targets. He was assured that, being such a welcome visitor, he did not worry about the consequences. It was just as well, for after taking careful aim he missed the target and managed to chip a piece out of a jug!

A corner of the showground set out specially for the children delighted Mr. and Mrs. Carney. The former remarked: “It is a pity I have got too old to go on some of these things.“ Afterwards, however, he mounted a miniature roundabout with 4 ½ year old Patricia Pleasant as his guest, while Alderman Freckingham had with him June Commander, aged 4.

Hoop-la and cocoa-nut shies were the next things to occupy the Lord Mayor’s attention. These were followed by a ride on the Jumping horses, and then a tour lasting over an hour was finished.

The Lord Mayor told the “Post“: “I visited many pre-war Goose Fairs, but I don’t think any of them were up to the standard of the present one.“ — First Post-War Goose Fair Opens. Nottingham Evening Post. Thursday, 4 October 1945. Page 1, col. 3.

First Post-War II Goose Fair Opens. Nottingham Evening Post. Thursday, 4 October 1945. Page 1, col. 3.

Video of various Goose Fair years, from early 1900s to approximately 1960s:

References

| ↑1 | ”about the purchase of a pair of trousers at the ‘Goose Fair Nottingham’, by John Trussell, a steward of the Willoughby family from Wollaton.” — Breese, Chris. Cheese riots and dragoons: The complete history of Nottingham Goose Fair. Notts TV. 3 October 2016. Accessed October 2021 at https://nottstv.com/cheese-riots-and-dragoons-the-complete-history-of-nottingham-goose-fair-2016/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Breese, Chris. Cheese riots and dragoons: The complete history of Nottingham Goose Fair. Notts TV. 3 October 2016. Accessed October 2021 at https://nottstv.com/cheese-riots-and-dragoons-the-complete-history-of-nottingham-goose-fair-2016/ |

| ↑3 | Breese, Chris. Cheese riots and dragoons: The complete history of Nottingham Goose Fair. Notts TV. 3 October 2016. Accessed October 2021 at https://nottstv.com/cheese-riots-and-dragoons-the-complete-history-of-nottingham-goose-fair-2016/ |