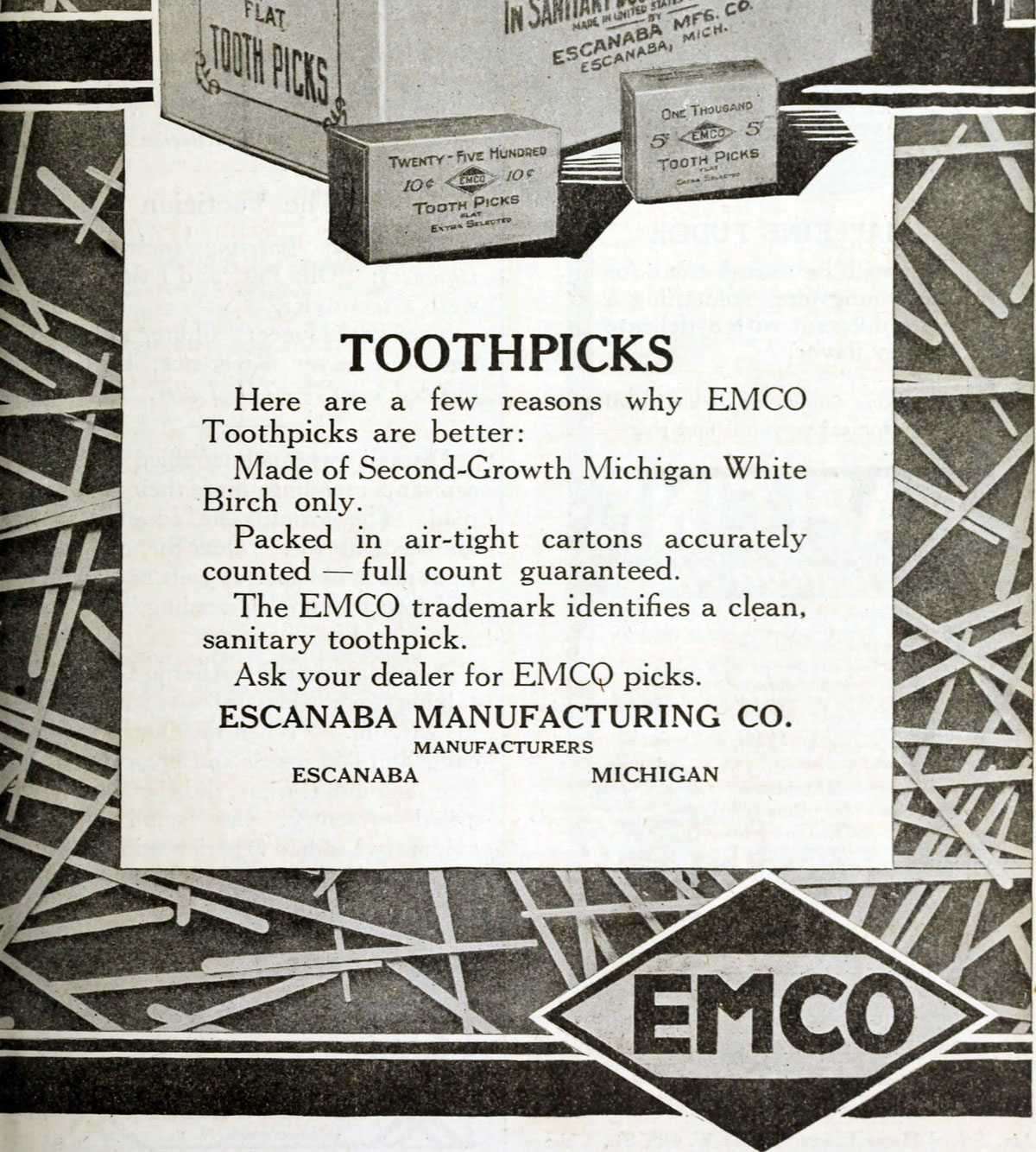

Toothpicks. Abubibolabu/ Pixabay.com / 2015 / CC0 1.0

A toothpick is a small tool originally designed to clean teeth with.

It can be round or flat. It is usually made of wood, but it can be made of plastic, metal, bamboo or even bone.

At least one end will be sharp and pointy to fit between teeth and remove any lodged food.

Uses of toothpicks

The kitchen uses for toothpicks may now be more important than their original purpose. They can be used:

- to serve hors d’oeuvres with;

- as a food fastener, particularly in sandwiches such as Club Sandwiches;

- for cocktails to hold things such as olives;

- to test if cakes are done.

You can get coloured ones, but their colour can leech into food.

Some toothpicks have a splash of coloured cellophane strands attached at the end, making them a particularly festive adornment for hors d’oeuvres.

Flavoured toothpicks

You can get flavoured toothpicks for chewing on, with flavours such as cinnamon, mint, bacon, etc. Be sure to use plain, unflavoured toothpicks when using toothpicks for testing baked goods or fastening food together.

How toothpicks are made

To make wooden toothpicks, logs are debarked, then put through a roller which cuts thin long strips off them. The machine then cuts these strips widthwise into toothpicks. The toothpicks are then put into a dryer to harden them, then put into a polisher to make them smooth. A machine sifter weeds out damaged ones, then a roller passes them to be automatically boxed.

The world’s largest exporter of toothpicks is Brazil.

Nutrition

Toothpicks are very dangerous if swallowed. When using as a food fastener, always do so in a very obvious way.

History Notes

Toothpicks been around forever, though they now supplanted by dental floss and toothbrushes. Because even a stiff stalk of grass could be used as a toothpick, it was the most accessible (if not the only) means for dental hygiene.

In antiquity, metal ones were made for the better off. Wealthy Romans had theirs made of silver.

Starting in the 1500s, nuns at the Mosteiro de Lorvão in the Coimbra region of Portugal made Toothpicks from orangewood. Called “palitos de Coimbra“, they were 15 to 25 cm long (6 to 10 inches), and were considered high quality personal items that you used over and over. People in neighbouring villages started making them as well. The knack for making toothpicks followed the Portuguese to Brazil.

Disposable, commercially-made toothpicks came to the world through a Charles Forster, born 1826 in Charlestown, Massachusetts. He went to Brazil to work for his uncle who had a trading business there. In Brazil, Charles saw that people there had handmade toothpicks. From watching them, he got the idea to make cheap, mass-produced ones.

He bought out a patent from a Benjamin Franklin Sturtevant for a machine that could make strips of wood veneer. Forster felt that the machine could be adopted for toothpicks. By 1870, he was set up to produce them. He used white birch, to get clean looking wood. He had his factory in Maine, close to the timber supply.

He had a hard time marketing them in Boston at first. The tradition in New England had been to just whittle a toothpick whenever you wanted one. Charles hired people to go into stores and restaurants asking for them, and then later he’d pay a sales call to the stores and restaurants asking if they wanted him to supply them. Soon it even became fashionable for both men and women to chew a toothpick in public, especially outside fancy restaurants, to imply that they had just eaten in a good quality establishment.

Literature & Lore

In most Western countries, it is now considered rude to use a toothpick for cleaning teeth in public.

“Cleanse not your teeth with the Table Cloth Napkin Fork or Knife but if Others do it let it be done with a Pick Tooth.” — Washington, George. Rules of Civility & Decent Behaviour in Company and Conversation: a Book of Etiquette. Williamsburg, VA: Beaver Press, 1971.

Sources

Petroski, Henry. The marketing genius who brought us the Toothpick. Slate Magazine. 31 October 2007. Retrieved November 2009 from http://www.slate.com/id/2177109/

Petroski, Henry. Looking for a good Toothpick — for 2 million years. Los Angeles Times. 30 October 2007.

Toothpick ad in: American cookery, 1914, page 386. / Public Domain