Archestratus was a Greek writer who lived around 350 BC, on the island of Sicily just off the boot of the Italian peninsula. Though probably not a cook himself, he was a gourmand and a lover of good food and eating.

His world

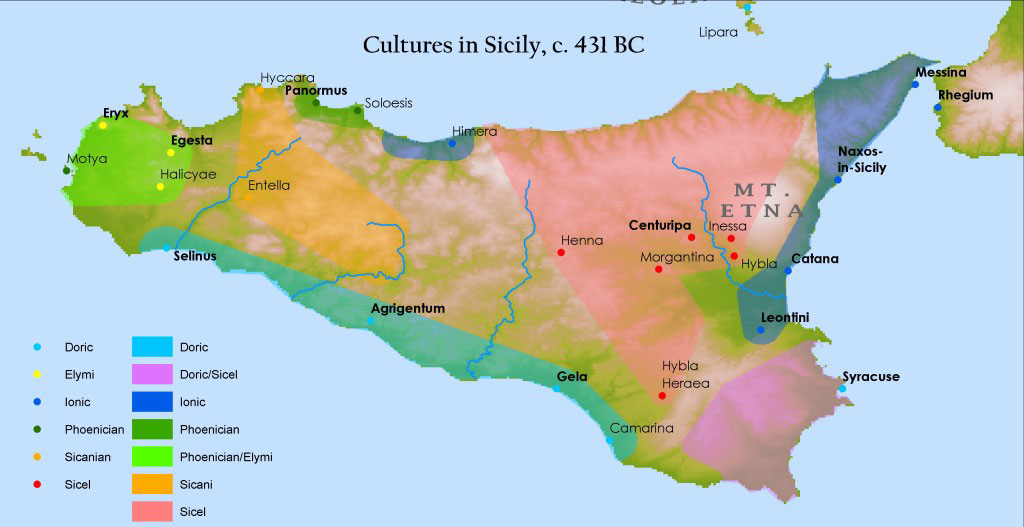

Significant parts of Sicily were Greek colonies from about 750 BC to 250 BC. (To be clear, other cultures such as the Phoenicians and the Carthaginians, as well as the indigenous Sicilian people, lived there too.)

Archestratus lived in either the Sicilian cities of Gela or Syracuse (both of which are still extant.) He did some of his writing in Gela.

Ancient Greek and other colonies in Southern Italy (Magna Graecia) circa 430 BC. Abu America / wikimedia / 2007 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The Greek homeland was considered poor compared to the rich agricultural lands of Sicily and its wealthy cities. Sicily had come to be identified with good eating and sophisticated food by the 400s BC. Plato, in fact, thought that the Greek Sicilians were obsessed with food to the point of being gluttonous.

His writings

Archestratus wrote a poem called ‘Hedypatheia‘ (meaning “Pleasant Living” or “Life of Luxury”), in a verse style that parodied the style of older, esteemed Greek poets.

The poem has long since been lost, but we have access to 62 fragments of it, about 300 lines in total. In 228 AD, the writer Athenaeus still had access to the poem, and had his dinner table guests quote it in his “Philosophers at Dinner” book. These are the 62 fragments that we now have.

Not a cook but a gourmand

Archestratus was probably not a full-time cook himself, because cooks wouldn’t have been educated enough generally to write, let alone write poetry. He must, though, have been a lover of good food, and must have interacted with his cooks and servants a good deal because of the knowledge that comes through in his poem.

In the poem, Archestratus shows just how cosmopolitan classical Greek food had become, drawing on food from throughout the known Mediterranean world at the time. He gives advice on how to pick out the best food, and where to travel to get it. Most of the poem seems to have been focussed on fish.

He advises that fish should be cooked and flavoured simply, with the use of stronger flavours reserved only for lesser quality fish. He disliked the habit people in Syracuse had of adding cheese to fish dishes (a dislike which Italians in general now share with him.)

A sample of his advice

“But I say to hell with saperde, a Pontic dish,

And those who praise it. For few people

Know which food is wretched and which is excellent.

But get a mackerel on the third day, before it goes into salt water

Within a transport jar as a piece of recently cured, half-salted fish.

And if you come to the holy city of famous Byzantion,

I urge you again to eat a steak of peak-season tuna; for it is very good and soft.” — Archestratus, fragment 39. Olson and Sens translation.

“Do not allow anyone come near you when you bake sea wolf neither Syracusan nor Italiote, for they do not know how to prepare them decently. But they ruin them and make a mess out of them with cheeses and sprinklings of the liquid vinegar and the silphion brine.

“First I shall recall the gifts to humankind and fair-haired Demeter, friend Moschus: take them to your heart. The best one can get, the finest of all, cleanly hulled from good ripe ears, is the barley from the sea-washed breast of famous Eresus in Lesbos – whiter than airborne snow. If the gods eat barley, this is where Hermes goes shopping for it.

“But if you go to the prosperous land of Ambracia and happen to see the boar-fish, buy it! Even if it costs its weight in gold, don’t leave without it, lest the dread vengeance of the deathless ones breathe down on you; for this fish is the flower of nectar…

It [Ed. Rhodian dogfish] could mean your death, but if they won’t sell it to you, take it by force… afterwards you can submit patiently to your fate.

“There you have the advantage over all the rest of us mortals, citizen of Messina, as you put such fare to your lips. The eels of the Strymon river, on the other hand, and those of lake Copais have a formidable reputation for excellence thanks to their large size and wondrous girth. All in all I think the eel rules over everything else at the feast and commands the field of pleasure, despite being the only fish with no backbone.

“The bonito [Ed. tuna], in autumn when the Pleiades set, you can prepare in any way you please. . . . But here is the very best way for you to deal with this fish. You need fig leaves and oregano (not very much), no cheese, no nonsense. Just wrap it up nicely in fig leaves fastened with string, then hide it under hot ashes and keep a watch on the time: don’t overcook it. Get it from Byzantium, if you want it to be good. . . .” — Archestratus, fragments 59 to 62. Olson and Sens translation.

Literature & Lore

“Archestratus has written his book and is held in esteem by some, as if he has said something useful. But he is ignorant of most things and tells us nothing.” — Dionysius The Law Maker, fragment 2.15 to 26KA, written sometime in the 4th century BC, preserved in Thenaeus 405a-b.

Further reading

Shaw Carl. “ΣΚΟΡΠΙΟΣ OR ΣΚΩΡ ΠΕΟΣ? A sexual joke in Archestratus’ Hedypatheia.” The Classical Quarterly, vol. 59, no. 2, 2009, pp. 634–639., doi:10.1017/S0009838809990255.

Wilkins, John and Shaun Hill. Archestratus: Fragments from the Life of Luxury. London: England. Prospect Books. 2011.

Depiction of food preparation in the Ancient Greek world. coursousa / Pixabay.com / 2007 / CC0 1.0