Béaltaine. © Merimariko / pixabay.com / 2012 / CC0 1.0

Béaltaine is the evening of the 30th of April.

Béaltaine (aka Beltane, Beltaine) was a Celtic festival to mark the start of summer. It was celebrated throughout what is now the UK and Ireland. After long winters of staying close to your home and isolated farms, it provided communities with a chance to start coming together again outside in the nicer weather, and to express hopes for a good summer for the crops and animals. It was rich with many associated traditions which have now been lost.

Bel was the Celtic sun god. Celts measure their holidays, like the Jews, from sunset to sunset. So, Béaltaine actually began on May Eve — that is, the evening of the 30th of April.

Bonfires were lit either on the May Eve (evening of 30th April), or on the 1st of May or anytime up to the third of May. In Wales, the bonfires would contain wood from nine different kinds of trees. Sometimes the fire was made in a hole cut in the ground; sometimes in a trench cut in the shape of a square, leaving the grass in the middle of the square; sometimes two fires would be built close together. In the early times, the fires would be set by druids with incantations. The fires were kept burning throughout the night.

Jumping over or passing between two fires was thought to either purify you, bring good luck in finding a mate, or assure an easy childbirth if you were pregnant.

Couples could choose to “tie the knot” that day, becoming handfast to each other with a ribbon joining their hands. Such unions gave couples a year and a day to see how they liked married life with each other. If by the next Beltane, they chose not to stay together, they would be considered divorced and free to try a union with someone else (this practice stopped, of course, when the Church arrived.)

The livestock were also either driven around the fire sunwise (clockwise), or made to pass between two fires (this custom lasted longest in Ireland.) In the days following this, the livestock would then be led up to their summer pastures. Some surmise that this purification ritual may actually have had the practical effect of the heat driving lice off the animals which had been kept in close quarters with each other all winter indoors.

Cattle waiting to pass between the fires. © Merimariko / pixabay.com / 2012 / CC0 1.0

Straw on a pitchfork would be set alight, then people would run around holding it up in the air to scare off the witches (sometimes a burning torch was used instead.) Ashes from the fires were spread about to protect the fields from any witchcraft that might affect the crops. Some say it was to bless the fields, but it was really more to cause the absence of curses.

Some communities followed a “beating the bounds” tradition of marching around the boundaries of the village with flaming torches. This also allowed the men to note which of the village fences would be needing repair that summer.

Before leaving for the communal bonfires, fires were put out at home, and unheated food served. While your fire was out, you’d clean your hearth and chimney.

You’d bring some fire home with a torch from the Béaltaine fire to relight your hearth at home the next morning.

Even though Béaltaine marked the start of summer, when food from the land would become plentiful, it was a time when food wasn’t actually abundant. The new food from this year wouldn’t have started yet, and the last stores from the previous year would be dwindling. People still made a feast of what they had, though, and everyone was expected to bring some food to the feast. Many would make porridge to serve. A woman considered it a matter of pride to be able show that she could serve a porridge — it was a sign that she was a good household manager to still have enough grain left to make it. No doubt many women would have skimped however little they had to be able to show others that she still had grain.

A Béaltaine caudle was made from eggs, butter, oats, and milk, and some of it poured on the ground as a libation. Special Béaltaine bannock was also made, along with a sheep’s-milk cheese.

At home, on your own doorstep, you would leave offerings of a bannock and something to drink for the Faeries. Your best chance of spotting a faery was at twilight on 1st May, and again at midnight.

In some places, a bannock was broken up and the pieces put into a hat. One of the pieces would be blackened with charcoal from the fire, and whoever drew it would become the “cailleach”, the scapegoat. People made a pretend show of trying to push him into the fire, and at the end of it, he would have to leap over the fire three times.

Beltane was the only Quarter Day (the 4 days of the year marking the change of the four seasons) which didn’t get co-opted by the Church into another holiday.

Beltane was celebrated in parts of Scotland up to the end of the 1700s before it died out.

In modern Britain, there has been a revival of Beltain festivals. Since 1987, a Beltane Fire Festival has been held in Edinburgh. There is a procession with a May Queen, the Winter King and the Green Man. Fire festivals are also held in Thornborough Henge near Ripon in North Yorkshire and at Butser Ancient Farm south of Petersfield in Hampshire.

#Béaltaine

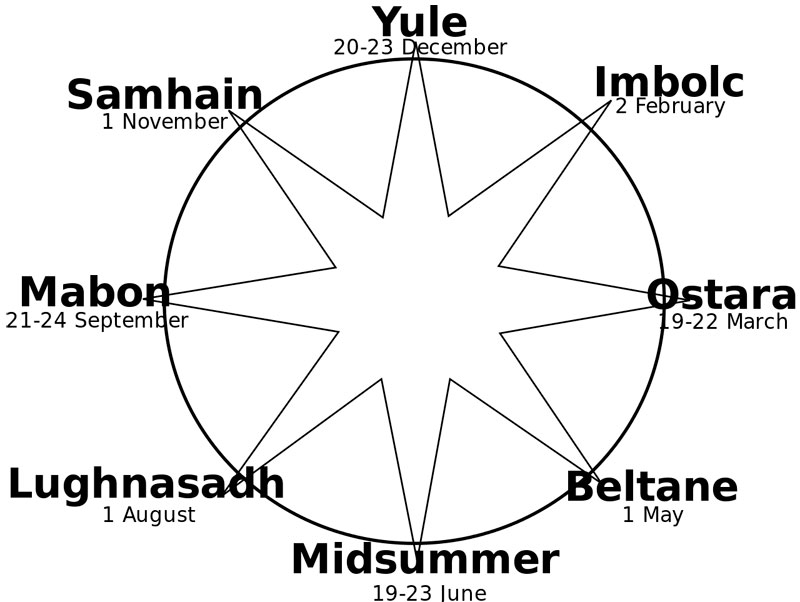

Celtic wheel of the year showing where Béaltaine fits into the yearly cycle. © The Wednesday Island / wikimedia.org / 2008.

Language Notes

Béal was the sun god Bel; “taine” refers to “tinne”, the Celtic word for fire. The day was called “Shenn do Boaldyn” on the Isle of Man, and “Galan Mae” in Wales.

The Scots Gaelic word for a bonfire was a “coelcerth”.

Sources

Lambert, Victoria. Beltane: Britain’s ancient festival is making a comeback. London: Daily Telegraph. 27 April 2012.