Blue Wensleydale cheese is a double-cream blue cheese.

It has blue veins like Stilton, though it is much milder and less salty, and more creamy rather than crumbly. In its heyday, it compared head-to-head with Stilton for recognition and popularity.

As of the 2020s, a large producer of it is “Wensleydale Creamery” of Hawes, Yorkshire.

Production

The cheese is made from pasteurized cow’s milk. It is pressed, wrapped in muslin cloth and set in a maturing room to age. After a few weeks, the cheese is pierced to allow air in so that the mould can develop.

Factory-made cheese is aged about 2 months. In the past, farmhouse versions would be aged up to 6 months.

Equivalents

1 cup Blue Wensleydale cheese, crumbled ≈ 100 g ≈ ¼ pound

Substitutes

Another mild blue cheese

History Notes

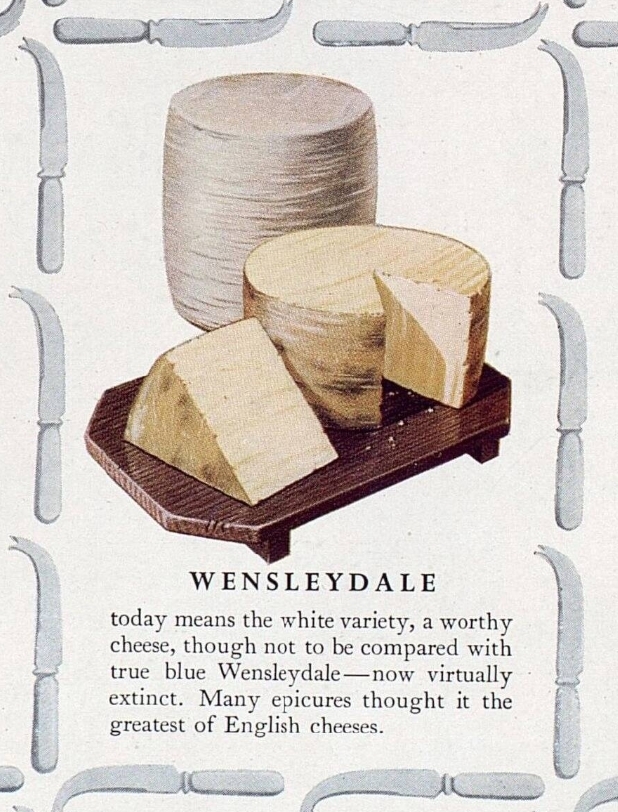

Wensleydale was originally a blue cheese. Now, white is better known and the Blue is considered the novelty cheese.

Up until the 1920s, just saying “Wensleydale” typically meant Blue Wensleydale, though both white and blue were made. The cheeses were made in two shapes: the white was made in low, flat wheels not intended for aging, while the cheese intended to be aged for blue was made in tall cylinders.

“Take the case of Wensleydale, which is of two classes, the flat and the Stilton-shaped the former being meant to sell quite new, whilst the latter meant to be kept to ripen and become blue.” [1]Rowntree, A. Varieties of Cheese. Christchurch, New Zealand: The Lyttelton Times. Friday, 27 December 1912. Page 10, col. 3.

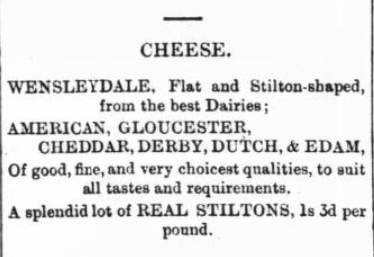

For Christmas 1882, the Middlesborough, Durham merchant Amos Hinton advertised that he was selling both the white (flat) and blue (Stilton-shape) Wensleydales.

The blue was made from summer milk, as it was considered the best milk. White Wensleydale would be made from spring, autumn and winter milk (if any winter milk were available). [2]Behr, Edward. Wensleydale. The Art of Eating. Accessed October 2022 at https://artofeating.com/wensleydale/

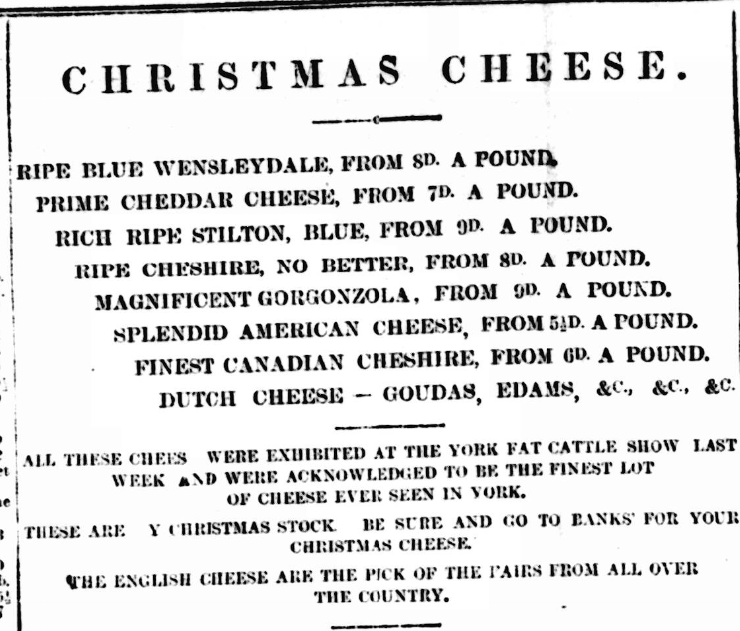

In 1889, the Blue Wensleydale commanded a price just slightly less than Stilton, of 8 pence a pound compared to 9 pence a pound for the Stilton.

1889 ad showing price of Blue Wensleydale. The Yorkshire Chronicle. Saturday, 21 December 1889. Christmas Supplement, page 1.

One cheese expert considered that making Blue Wensleydale was more profitable than making Stilton:

“WENSLEYDALES AND STILTONS. Of the hard varieties of cheese, probably the ones that pay best are the blue-veined Wensleydales and Stiltons when well made, but considerable skill and experience is needed to produce really fine cheese, and they have to be kept so long to ripen and become blue that if many are made a proper room for storing them in is necessary, which is perhaps a drawback to the farmer; also he has to wait so long before they can be turned into money. For the small farmer with only a little milk Wensleydales would be more suitable than Stiltons, as they are often made in small sizes of from 4 lb to 7 lb, and real Stiltons are rarely made smaller than from 10 lb to 12 lb. In the case of the former variety, too, the yield per gallon is probably rather greater than in the case of Stiltons…” [3]Rowntree, A. Varieties of Cheese. Christchurch, New Zealand: The Lyttelton Times. Friday, 27 December 1912. Page 10, col. 3.

A 1930 editorial comment notes that factory-made Wensleydale was starting to displace farm-house, and that a preference for the ‘new’ Wensleydale (the white) was starting to overtake that for the aged (the blue):

“Choice Cheeses of England: Under the above title an article appeared on this page on Tuesday, but “Yorkshire folk,” writes N.R.Y., “cannot allow it to pass unchallenged, as no allusion is made to their own products. A prime ‘blue’ Wensleydale runs a Stilton very close and requires quite as much skill to produce. As in the Stilton-making districts, so in Wensleydale, cheese-making is looked upon as an art, and certain farms and families bear a long-standing reputation for turning out good blue cheeses. Although the tendency to-day is for the milk from a wide area to be collected by, or taken to, a factory where it is made into cheese, there are still farmers that cling to the old way of making it at home. Many of the larger farms are provided with well-equipped dairies and cheese-ripening rooms to accommodate a season’s make, and it used to be the custom for the cheese to be kept until autumn — or the back-end,’ to give it the local term — and then grocers and provision dealers from the towns would come up and buy for their Christmas trade. Nowadays, the wholesaler goes round to collect the cheeses new, and takes them into the towns, where they find a ready sale, the popular taste being for new cheese rather than the mature.” — This World of Ours: Choice Cheeses of England. Leeds, Yorkshire: The Yorkshire Post. Saturday, September 13, 1930. Page 8, col. 2.

At the start of World War Two, there were still 170 people making it as a farmhouse cheese. But wartime cheese regulations demanded standardization of cheeses, and the blue dropped out of production. [4]Behr, Edward. Wensleydale. The Art of Eating. Accessed October 2022 at https://artofeating.com/wensleydale/

During World War Two, the commercial production of the blue type of Wensleydale was halted for the duration of war:

“The blue-veined cheeses — Stilton, Dorset Blue and Blue Wensleydale — are also in part mould-flavoured, but their manufacture is also prohibited during the war.” [5]How Butter and Cheese are Made. London, England: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. Friday, 1 September 1944. Page 133, col. 1.

Despite this, it appears some private-consumption farmhouse production of Blue Wensleydale continued:

“”At one of the farms where I stayed they made one cheese (four or five pounds) daily during the summer. One gallon of milk made one pound of cheese. Certain cheeses, spotted intuitively by the farmer, are kept on the stone shelf for six months or more and are turned every day. When opened at Christmas they prove to be ripe blue Wensleydales.” — Rhapsody In Blue. Yorkshire Gossip. Bradford, Yorkshire: Bradford Observer. Wednesday, 12 March 1941. Page 4, col. 7.”

After the war, while production of the white variety slowly picked up and recovered, production of the blue did not:

“What is the quality of to-day’s Wensleydale cheese?… The white variety, while still delightfully mild and palatable… has lost some of its characteristics…. Blue Wensleydale, which many of us thought the finest of all English cheeses, is not being made at all, though Stilton, its only rival, is obtainable off ration and off points — at a price. The Wensleydale makers are faced with two difficulties — marketing and lack of skilled workers.” — Illingworth, John L. More Wensleydale cheese — but not for the towns. The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Mercury. Monday, 16 January 1950. Page 3, col. 4

In 1954, the West Riding Wine and Food Society was able source Blue Wensleydale from somewhere to feed to its members:

“In the best Northern tradition the meal began with Yorkshire pudding, eaten as a separate course with gravy. After that… there was roast beef, with roast potatoes and honest English vegetables, apple pie and cream, Blue Wensleydale cheers, and coffee.” — A reet good meal. Leeds, England: Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Wednesday, 6 October 1954. Page 4, col. 6.

In 1957, a society columnist mentioned that only one person was producing blue Wensleydale:

“Unfortunately we have lost some of our famous English cheeses during recent years — they have not reappeared after the wartime restrictions, and now there are few people who can make them. For instance, although white Wensleydale is now in good supply, there is only one man still making blue Wensleydale, and the whole of his output goes to the dining rooms of the Cunard’s Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth.” — Stanley, Ailsa. Wine and Cheese Parties Are Fun. Nottingham, England: The Guardian Journal. Friday, 14 June 1957. Page 2, col. 5.

Another writer mentioned that only one producer was in operation:

“One of the saddest losses is Blue Wensleydale. Production of this was stopped during the war, and the original conditions of those old blueing rooms have never been perfectly captured since. Only one man is obtaining anything near the original quality now.” — Taste these cheeses and enjoy delicious variety. Nottingham, England: Nottingham Guardian. Tuesday, 18 June 1957. Page 3, col. 3.

Perhaps the producer in question was T.C. Calvert (“Kit Calvert”) of Hawes, Yorkshire (see below, “1950s revival efforts”).

Production of the cheese continued to be limited during the following decades. One dairy that made it in limited quantities during the 1980s was Nuttall’s Dove Dairy in Hartington, Derbyshire, part of the Milk Marketing Board’s Dairy Crest conglomerate. [6]Watson, Bob. Window on Work. Derby, Derbyshire: Derby Daily Telegraph. Thursday, 18 March 1982. Page 13, col. 1. In 1995, they won a second prize in the Royal Bath and West Show’s Specialty Cheese Class for their blue Wensleydale. [7]Crest of Winning Wave. Ashbourne, Derbyshire: Ashbourne News Telegraph. Thursday, 8 June 1995. Page 2, col. 7.

By the second half of the 1990s, other dairies had entered into production of Blue Wensleydale, such as Millway Foods of Harby, Nottinghamshire, for which they won a silver medal in 1997 at the British Cheese Awards. [8]Cheesy grin for firm win. Nottingham, England: Nottingham Evening Post. Wednesday, 8 October 1997. Page 10, col. 7.

See entry on Wensleydale for more history.

1950s revival efforts

Efforts to revive the cheese commercially were made in the mid-1950s, but appear to have been hampered by a loss of the knowledge and skills after a production hiatus of over 15 years:

“There is news for gourmets and others from the little market town of Hawes. Efforts are being made to rediscover the secret of making blue Wensleydale cheese, remembered by the discriminating as a mild cheese of much virtue. The 200 gallons of milk a day received is only enough to carry out small-scale experiments, which are being directed to the recovery of formulae which will result in a return to traditional Wensleydale cheese after years of rationing discipline.

While the white cheeses of Wensleydale are not being overlooked, emphasis during the present experiments is on blue cheese which has not been made since 1939 and, even then, in small quantities. It is believed that the difficulty created by the absence of written recipes will be overcome. A large, cavern-like building, set into the hillside factory, is being used, and it is hoped to simulate conditions n the cellars in which Stiltons mature and the natural caverns in which Gorgonzola develops its blue veining. The man behind the experiments is Mr. T. C. [Ed: “Kit”] Calvert, manager and a director of the cheese factory. [Ed: Wensleydale Creameries Ltd formerly Wensleydale Dairy, later Wensleydale Creamery]

There are many factors to be considered, such as the temperature of the milk at the time the rennet is added, that at coagulation, the way curd is handled before it goes into the moulds, achievement of texture by grinding,’ and treatment in the presses. Then there is the mould atmosphere in which the cheeses must be stored.

One thing cannot be controlled. Before factory production of Wensleydale cheeses, the best were made on farms, where the milk was from cows grazed on herbage with particular qualities drawn from the soil in those parts. “But science has come to our aid now, and I believe we shall overcome that difficulty during our present experiments,” said Mr. Calvert. He is hoping this may be done by next summer.” — Hunt for secret of blue cheese in Wensleydale. Leeds, Yorkshire: Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer . Monday, 19 September 1955. Page 3, col. 8.

A woman, Maude Verity, believed that she had information that would prove useful:

MISS MAUDE VERITY, an Ilkley reader of The Yorkshire Post, has come to the help of the cheesemakers of Wensleydale. She read in our news columns last week that they were trying to rediscover the secret of making blue Wensleydale cheese — “remembered by the discriminating as a mild cheese of much virtue” — and that there were no written recipes to aid their researches. Miss Verity looked through some papers which she had kept from the days 36 years ago, when she took a course at Leeds University Training College for Dairy Work, at Manor Farm, Garforth, and she found what she believes to be the secret of making this cheese. The recipe and method are included in a record of how to make 16 types of cheese. Miss Verity drew it up neatly at the College in 1919, and it is a most comprehensive record. It includes the quantity of milk used, the temperature, the quantity of rennet, the stirring time and the time at which the whey was drawn.

All the cheeses in her list were made by her at Manor Farm. While working for the late Mr. Alfred Rowntree at his cheese dairy in Masham after leaving the College, she was one of three young women who made a first-prize winning Stilton for the Royal Show, when it was held at Darlington.

“If my recipe is strictly followed,” she says, “a blue Wensleydale cheese can be produced. Of course, it would have to stand at least four to five months before it acquired the blue mould. Most people prefer Wensleydale cheese fairly new, and when it is new, it is quite white.” She recalled that she and two other girls working for Mr. Rowntree used to rennet up to 1,000 gallons of milk a day. Some weeks before Christmas they worked a night shift, making Stilton cheeses for Christmas sale. At the beginning of the Second World War Miss Verity knocked seven years off her age to join the Army, and became a sergeant cook in Anti-Aircraft Command. She is hoping that her blue cheese recipe will be useful to Mr. T. C. Calvert, the well-known Wensleydale cheese manufacturer.” — The secret of blue Wensleydale Cheese. Leeds, Yorkshire: Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer . Wednesday, 28 September 1955. Page 4, col. 4.

Several other people who had previously been involved with the cheese came forward:

“The latest development in Mr. T. C. Calvert’s hunt for recipes making blue Wensleydale cheese is that Miss M. M. Sykes, of Thornhill, Dewsbury, who has long experience of cheese-making, is to travel to Hawes on Monday to spend a week as Mr. Calvert’s guest. She will compare her recipes with those of Mr. Calvert and of Miss M. Verity, of Ilkley, who has sent Mr. Calvert records she made in 1919.

Miss Sykes tells me she began work with Mr. Alfred Rowntree at Kirkby Overblow in 1906. When he introduced factory cheesemaking at Masham about 1909 she went him and remained there until 1921, when she moved to Wetherby to run her own dairy until 1926. Miss Verity worked under Miss Sykes at Masham.

Yet another of Mr. Rowntree’s cheesemakers has come Calvert’s aid. She is Mrs. Burton who now lives at Upgang Lane, Whitby. She learned her cheese-making at the Masham factory, and has sent Mr. Calvert much information. Mrs. Burton believes that Bishopdale milk was better than Coverdale’s for cheese.” — Blue cheese hunt. Leeds, Yorkshire: Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. Friday, 30 September 1955. Page 6, col. 5.

The Ministry of Food, which was still controlling milk distribution at the time, allowed some milk for experimentation:

“Mr. Calvert was allowed enough milk to continue experiments in one vat through which he hopes to develop the manufacture of blue Wensleydale cheese. He will soon be examining the detailed record of his own experiments, as well as a mass of information which he has received from all over the country, as the result of an article on his researches which recently appeared in The Yorkshire Post.

He hopes to arrive at a satisfactory formula during the winter months so that he will be able to start factory production of blue Wensleydale in May and June next year. Milk produced in these months is regarded as the best for the purpose.” — Cheeses return to Wensleydale from the bulb-fields. Leeds, Yorkshire: Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer . Thursday, 13 October 1955. Page 5, col. 5.

It is unclear in the archival newspaper record what Calvert’s ultimate results were, though perhaps he became the source of the limited supply mentioned above in the History section.

“Wensleydale today means the white variety, a worthy cheese, though not to be compared with true blue Wensleydale — now virtually extinct. Many epicures thought it the greatest of English cheeses.” — Guinness Guide to English Cheese. London, England: The Tatler. Wednesday, 16 December 1953. Page 2.

Literature & Lore

“Middleham, Thursday. NOWADAYS few farmers in the Yorkshire dales make cheese, the industry being largely in the hands of one or two factories, but at East Witton, near Middleham, Mr. Edward Preston, of Hammer Farm, still employs a dairymaid and turns out several cheeses a day.

Rabbits scuttled out of my path as I climbed up the hillside to the holding of this Wensleydale farmer, situated under the lee of a wood abounding in young pheasants. Arrived at the farm, I passed through a spotlessly clean, spacious kitchen, and by the side of a cheery fire Mr. Preston initiated me into some of the mysteries of cheese-making.

I asked him how long it took good Wensleydale cheeses to mature, and was told that they were saleable in from two to three weeks of making, but that the longer they are kept the better the flavour. A good cheese can easily be kept for six months.

“They all the better for the keeping,” said Mr. Preston. “They get to have a bit more smack about them and are not quite so tame.”

I discovered that it takes about a gallon of milk to make 1 ¼ lb. of cheese, but you won’t get a pound in June,” said Mr. Preston. “Another point,” he continued, “is that the richest land does not always produce the best cheese, but as to why this should be I cannot explain.”

One strange fact that emerged from our chat was that neither as much nor as good cheese is obtainable on a thundery day as when there is no thunder about.

I was then taken into the dairy where cheeses lay in rows upon shelves and under press, emitting a delicious aroma. Cheeses are, I find, made in tins to-day, the old-fashioned “tubs” having long been discarded.

“You make a blue Wensleydale, don’t you?” I asked. “How do you get the colour — if I’m not prying into a trade secret?”

“Well, we don’t really bother much about them nowadays,” replied Mr. Preston,” but the blue tint is obtained by maturing them in a rather warmer place than the others.”

“And you find cheese-making pays?”

“Oh, yes,” came the ready response. “Why, I feed my pigs on the whey left over from cheese-making, and the saving effected enables me to pay my dairymaid’s wages.” — Prime Wensleydale: Secrets of Cheese-making. Bradford, Yorkshire: The Yorkshire Observer. Friday, 9 October 1936. Page 10, col. 4.

The mid 20th century English food writer Ambrose Heath thought Wensleydale to be one of England’s greatest cheeses, and that blue Wensleydale was superior to white.

“…white Wensleydale is a very forlorn relation of the true cheese. Mr. Heath, however, rates blue Wensleydale above Stilton, and can find no words to describe it adequately.” — The pleasures of Northern cheeses. (Review of English Cheeses of the North by Ambrose Heath.). Halifax, Yorkshire: Halifax Daily Courier and Guardian. Friday, 8 March 1957. Page 11, col. 3.

Sources

Wensleydale Creamery. The secret to Wensleydale Blue. 6 May 2020. Accessed October 2022 at https://www.wensleydale.co.uk/blog/the-secret-to-wensleydale-blue/

References

| ↑1 | Rowntree, A. Varieties of Cheese. Christchurch, New Zealand: The Lyttelton Times. Friday, 27 December 1912. Page 10, col. 3. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Behr, Edward. Wensleydale. The Art of Eating. Accessed October 2022 at https://artofeating.com/wensleydale/ |

| ↑3 | Rowntree, A. Varieties of Cheese. Christchurch, New Zealand: The Lyttelton Times. Friday, 27 December 1912. Page 10, col. 3. |

| ↑4 | Behr, Edward. Wensleydale. The Art of Eating. Accessed October 2022 at https://artofeating.com/wensleydale/ |

| ↑5 | How Butter and Cheese are Made. London, England: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. Friday, 1 September 1944. Page 133, col. 1. |

| ↑6 | Watson, Bob. Window on Work. Derby, Derbyshire: Derby Daily Telegraph. Thursday, 18 March 1982. Page 13, col. 1. |

| ↑7 | Crest of Winning Wave. Ashbourne, Derbyshire: Ashbourne News Telegraph. Thursday, 8 June 1995. Page 2, col. 7. |

| ↑8 | Cheesy grin for firm win. Nottingham, England: Nottingham Evening Post. Wednesday, 8 October 1997. Page 10, col. 7. |