Catherine de’ Medici was Queen of France from 1547 until 1559 and Queen Mother from 1559 to 1589. While she had a great influence over French politics for over 40 years, she is also said to have had an influence over the revolution of French cooking during that time as well.

Catherine de Medici’s foodie legacy

Catherine de Medici is credited with introducing many food innovations to France. She’s said to have taught the French how to eat with a fork, and introduced foods and dishes such as artichokes, aspics, baby peas, broccoli, cakes, candied vegetables, cream puffs, custards, ices, lettuce, milk-fed veal, melon seeds, parsley, pasta, puff pastry, quenelles, scallopine, sherbet, spinach, sweetbreads, truffles and zabaglione. She is reputed to have arrived in France with her own personal cooks, pastry cooks, chefs, confectioners and distillers. On a good day, she’s even said to have invented women’s knickers.

As always, the truth is less easy, and less exciting. Catherine came to France relatively poor, and for her first ten years there, her husband’s mistress had all the influence and she had none. It’s only in the mid-1800s in France that she started being credited with first a few items, and then more and more. Prior to that, though, there is actually no earlier documentation for any of it. The kindest response one can really give to such myths is that perhaps she helped such food and food-related items to gain more acceptance.

Catherine and the fork

The fork, for instance, was used back her in native Italy at a time when the rest of Europe still looked on it as being a bit pretentious; her using it may have encouraged more around her to try it as well.

A fork from the 1500s, made of iron and bone. Musée de Laon. Bassil / Wikimedia / 2008 / Public Domain

Catherine’s origins

Catherine was born Florence, Italy on 13 April 1519. Her full name was Caterina Maria Romola di Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Her father was Lorenzo de’ Medici II; her mother was a French princess, Madeleine de la Tour d’Auvergne. Her uncles were powerful Popes in Rome.

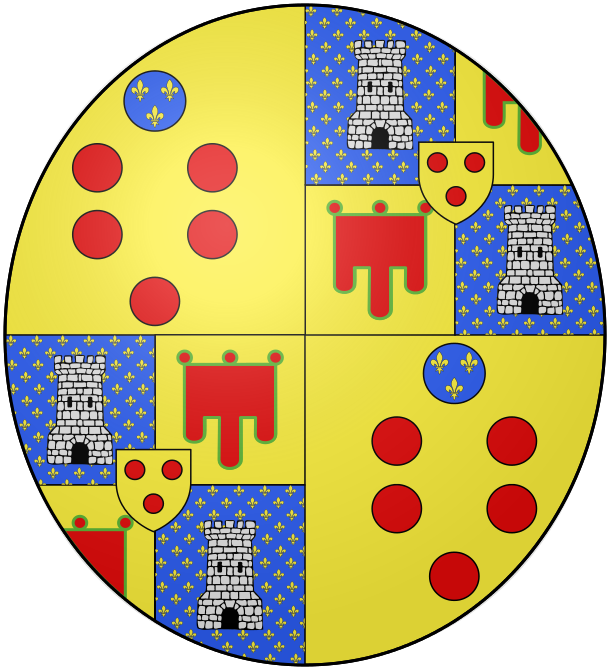

Catherine de Medici coat of arms, incorporating the famous Medici balls. Odejea / Wikimedia / 2009 / CC BY-SA 2.5

Catherine arrives in France

In October 1533 in Marseilles, she married the French Prince Henry, who was second in line to the throne in France at the time. His father the king was Francis I. Catherine was only 13 ½ years old at the time.

Catharine’s wedding to Henry (painted 12 years after the event). Vasari / Wikimedia / 1550 / Public Domain / PD-1923

The marriage was designed to garner for Henry’s father, Francis I, the favour of Pope Clement VII, who was also both a Medici and Catherine’s uncle. Clement VII, however, died before a whole year was out, passing away on 25 September 1534.

As Catherine didn’t arrive in France with enough money to make her interesting on her own without her illustrious uncle, she just faded into the background for a while, and her husband even acquired a mistress, Diane de Poitiers.

On 31 March 1547, her husband became King Henri II, and Catherine became the Queen of France.

The monogram of Henri II and Catherine de Medici made with an H and two interlaced Cs. Fireplace in the Queen’s bedroom at Château de Blois. TwoWings / Wikimedia / 2006/ CC BY-SA 2.5

Henry and Catherine would have ten children, three of whom didn’t survive infancy, but four boys and three girls did.

Their eldest son Francis married Mary Stuart, Queen of the Scots, in 1548 when Mary was only six years old and he himself was only four. It was an arranged marriage to settle an alliance between Scotland and France. The marriage didn’t actually take place until 10 years later, on 24 April 1558.

Brazilian ball held for Henry II in Rouen October 1 1550. A Brazilian village was created, and 50 Brazilians imported to people it. Anonymous / Wikimedia / 1550 / Public Domain / PD-1923

Catherine thrives as a widow

Life really only began for Catherine when she was 40 years old when her husband Henri II died on 10 July 1559.

Henri had gifted his mistress, Diane de Poitiers, with an estate known as the Chateau de Chenonceau. One of Catherine’s first acts was to turf Diane out of there, and make it her own favourite residence, greatly expanding the gardens and adding a chapel and a library.

Chateau de Chenonceau. Ra-smit / Wikimedia / 2008 / CC BY-SA 3.0

At the Chateau de Chenonceau, there were extensive flower and vegetable gardens along with a variety of fruit trees. Stone buttresses protected the gardens from the river’s periodic flooding. Spsergio / Wikimedia / 2007 /CC BY-SA 3.0

Wine cellar at Chateau de Chenonceau. Dennis Jarvis / Flickr / 2014 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Their son Francis (born 19 January 1544) became King Francis II at the age of 15. Catherine held the first ever fireworks display at the Chateau de Chenonceau to celebrate.

Sadly, Francis II died only a year and a half later at the age of 16 from an ear infection on 5 December 1560. For the short time that Francis was on the throne, it was his wife Mary Stuart who really ran things. Catherine detested the daughter-in-law who didn’t know her place, so as soon as Francis shuffled off, Catherine gave Mary a one-way ticket back to Scotland.

Upon Francis’s death, her second son Charles (born 27 June 1550), 10 years old at the time, came to the throne as Charles IX. Owing to his age, and no interfering wife, Catherine was in effect in charge.

In 1574, Charles died on 30 May at the age of 24, whereupon her third son, Edouard-Alexandre (born 19 September 1551) came to the throne as Henry III of France at the age of 22.

Catherine died 14 years later on 5 January 1589 of natural causes.

Catherine’s successors

Catherine’s son Henri III died 1 August 1589 by stabbing, with no heirs. But Catherine hadn’t loosened her grip on the throne of France yet, not even in her grave.

Her eldest daughter, Marguerite de Valois (1553 – 1615), and the person in the family who outlived all the rest, had previously married the Protestant Henri de Navarre (14 December 1553 to 14 May 1610) in Paris in August 1572. It was during Margot and Henri’s marriage that Catherine ordered the St Bartholomew’s Day massacre of all the Protestants were gathered in Paris to celebrate it. A “forced” marriage to begin with, the Protestant slaughter created an even greater distance between Margot and Henri that the marriage never recovered from.

Still, upon Henry III’s demise in 1589, Henri became Henri IV of France, and Margot, Queen Margot of France.

Ten years later, Henri and Margot’s marriage was finally dissolved in 1599, though she was allowed to keep her title of Queen. Margot had been the daughter of a King, the sister of three more Kings, and married to yet another.

Catharine. François Clouet / Wikimedia / 1560/ Public Domain / PD-1923

Videos

Sources

Wintroub, Michael. Civilizing the Savage and Making a King: The Royal Entry Festival of Henri II (Rouen, 1550). The Sixteenth Century Journal. Vol. 29, No. 2 (Summer, 1998), pp. 465-494