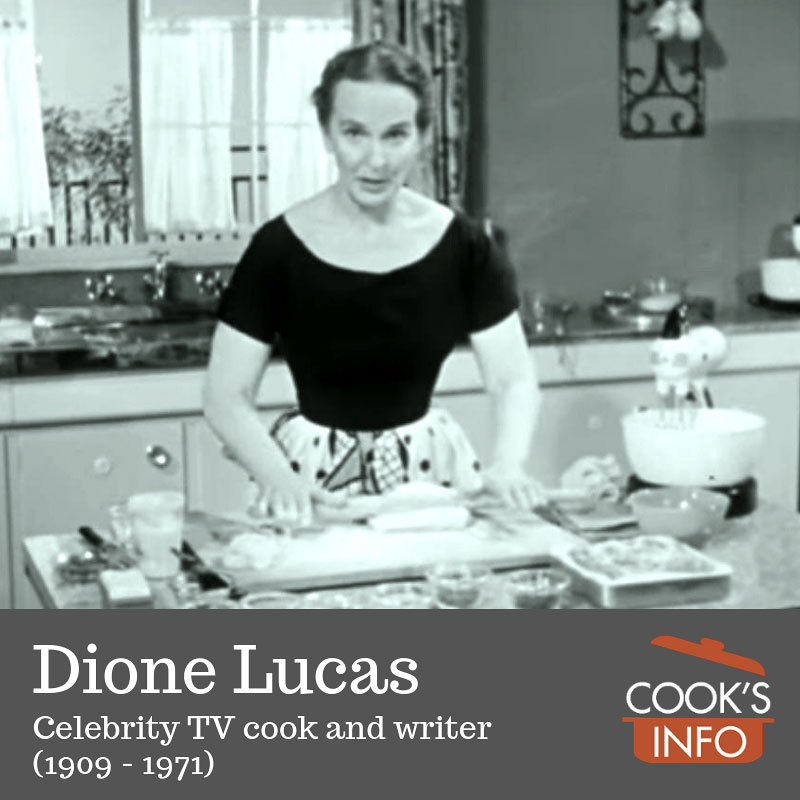

Dione Lucas was a food writer, teacher and starred in one of the first television cooking programs in the world.

Early life and family

Dione Lucas (née Dione Narone Margaris Wilson, 10 October 1909 – 18 December 1971) was born in Kensington, London, England to Henry and Margaret Wilson, and raised in France. [1]”Many accounts, including a frequently quoted 1949 profile of Dione published in the New Yorker, say Dione Narone Margaris Wilson was born in Venice in 1909. While the year is correct, the place isn’t. “There’s been some publicity romancing about this one,” Mark Lucas says, “but it was Kent, England, where the Wilsons had their home and Henry Wilson, Dione’s father, had his studios.” Actually, though, as Mark discovered when he located the argument settler — his mother’s birth certificate — she was born in Kensington.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. University of California Press: Gastronomica , Vol. 11, No. 4 (Winter 2011). Page 36. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/gfc.2012.11.4.34.

Her father Henry Wilson (1864–1934) was a sculptor, architect and painter in the Arts and Crafts tradition. He also made jewellery. He made the bronze doors for the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, as well as those for what used to be the Salada Tea Company’s Boston headquarters. Studies have been written of Henry in his own right for his own work and legacy.

Henry chose classical names for all the children. Dione was the youngest. A brother got named Guthlac, and two sisters were named Fiammetta and Pernel (who called herself Orrea).

Lucas was first trained as a jewellery maker by her father and then as a cellist at the Conservatoire in Paris. She then switched to cooking, studying at the age of 16 (according to some sources) at Cordon Bleu, where Henry-Paul Pellaprat was among her teachers. One of her classmates was Rosemary Hume. [2]”Catherine Baschet, with the publicity department at Le Cordon Bleu confirmed to Jeanne Schinto “that the often repeated idea that Dione was the school’s first female graduate is incorrect ‘for sure.'” But she did “confirm that a second young British woman, Rosemary Hume (1907–1984), studied at Cordon Bleu with Dione…” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 37.

“One of the first lessons at the Parisian school, Mrs. Lucas explained, was how to chop onions tearlessly. Outraged by having a young English woman in their classes, the French chefs ordered her to prepare onions. “I cried for 48 straight hours,” she said, “and then I cried no more. My initiation was over.” [3]Scribner, David. Cordon Bleu Chef Dione Lucas Opens ‘Brasserie’ Restaurant. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 8 November 1968. Page 14.

She became the first woman ever to graduate from Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, earning the “Grand Diplome.” After her diploma, she apprenticed at the Drouant Restaurant in Paris.

Marriage

In 9 April 1930, at the age of 21, she married Colin Lucas (1906 – 1984), an up and coming British architect.

The couple would have two children, first Mark who was born in England and then Peter who was born in Ottawa, Canada. Peter was born with cerebral palsy, but Marian Gorman said that “his mind was never affected”, and added that Peter “was a fully integrated member of the community of Bennington, Vermont.” [4]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 34. Peter died in 2008.

In 1933, Colin became associated with the architectural partnership of Connell Ward & Lucas.

Le Cordon Bleu, London

In the same year, 1933, Dione, in partnership with Rosemary Hume, set up a Le Cordon Bleu branch school in a one-room facility in Chelsea, London. They both claimed they took additional Cordon Bleu courses to be allowed grant diplomas, but writer Jeanne Schinto questions that that actually happened. [5]“I do not believe Rosemary Hume returned to Paris for further training in 1933 … [and] it seems unlikely that Dione had the time or inclination for a return visit of her own that year.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 38. Regardless, they were officially granted permission to bestow diplomas.

By 1935, they had moved the school to larger premises at 29 Sloane Street London, where they set up an adjoining small restaurant staffed by students from the school. Rosemary ran the restaurant, Dione did the teaching. Colin designed the restaurant for them in modernist style.

“Rosemary Hume and Dione Lucas were given the right to take the Le Cordon Bleu tradition to London, where they founded L’Ecole du Petit Cordon Bleu. After Hume secured a loan of £2,000 from family and friends, the pair were able to base the school in two ground-floor rooms which they rented in Jubilee Place, Chelsea. The large room was the kitchen, the smaller the office, and in a corridor to the street, they set up a few tables and chairs for passers-by to enjoy the efforts of the students. The loan was given on the premise of being paid back within 15 years, but in only two years the loan was repaid in full. In 1935 a tea shop at 11 Sloane Street became vacant, so Hume and Lucas took the opportunity to move the busy school to this site, from which they opened a restaurant called Au Petit Cordon Bleu – this was also the title the partners used for a popular book of recipes published in 1936. [6]History of our school | Le Cordon Bleu London. Accessed August 2019 at https://www.cordonbleu.edu/london/our-story/en

The restaurant was successful, but in 1937 Hume and Lucas dissolved their partnership. Strain of work and motherhood was cited.

The twilight before World War II

In 1937, Lucas began plans for another restaurant called “Au Petit Potager” at 142 Wigmore Street, also designed by Colin. But, it never opened. [7]”In 1937–1938, Colin designed another restaurant for her, Au Petit Potager, on Wigmore Street. It never opened.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 49.

Dione claimed that sometime during the late 1930s, she cooked at a hotel in Hamburg, Germany (possibly the Hotel Atlantik.) She said in her book, “The Gourmet Cooking School Cookbook” that she learnt there that Hitler was not a vegetarian:

“I learned this recipe when I worked as a chef before World War II, in one of the large hotels in Hamburg, Germany. I do not mean to spoil your appetite for stuffed squab, but you might be interested to know that it was a great favorite of Mr. Hitler, who dined at the hotel often. Let us not hold that against a fine recipe, though.”

This may, though, have been just an anecdote invented later by Lucas to hook her audiences:

“Lucas’ son Mark gave a revealing interview about his mother in which he ultimately deemed her “an extraordinarily complex person, but essentially unsophisticated in the best sense of the term.” He goes even further in deconstructing her: He thinks her books were largely ghostwritten save for her recipes, and he believes that some of the most-repeated anecdotes about her—even her own story about cooking for Hitler—were probably just tall tales.” [8]Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child. 14 December 2016. Chicago, Illinois: A.V. Club. Accessed July 2019 at https://tv.avclub.com/the-mother-of-all-celebrity-chefs-wasn-t-julia-child-1798255508

Her son Mark even doubts that she actually worked at a restaurant in Germany. He recalled that “his mother did go to Germany during that period”, but “for a holiday, not for employment.” [9]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 39.

In September 1939, World War II began.

Rosemary Hume closed the Cordon Blue school in London, of which she was now the sole proprietor, for the duration of the war. It would not re-open until 1945, with Constance Spry buying in and becoming one of the co-owners with Rosemary at that point.

Colin was working at the British Research Station at Princes Risborough on ways to reinforce concrete for defences, particularly air-raid shelters. Their son Mark was seven, and Dione was pregnant with their next son, Peter.

Dione Lucas in Canada

Dione left for Canada with Mark and her copper pots in tow — as well as three boys belonging to an Ursula Walford. She arrived in Ottawa to stay with Colin’s aunt and uncle there, Sir Gerald and Margaret Campbell. Gerald Campbell was Britain’s High Commissioner to Canada from 1938 to January 1941. Colin stayed behind in England to help with the war effort. The British Government transferred the Campbells down to Washington in January of 1941.

Dione Lucas’s arrival in New York

In 1941 or 1942 Dione Lucas moved down to Manhattan. The sources available as of yet all conflict with each other:

“Her arrival in this country from England via Canada in 1941 was concurrent with the war.” [10]Dugas, Gaile. Blue Ribbon Cook Says Good Food Takes Time and Effort. Lima, Ohio: The Lima News. 28 March 1950. Page 13.

A 1943 newspaper columnist says she arrived in New York in October 1942. “Mrs. Lucas is a pleasant British woman who has been in New York City since last October, when she came over with her nine-year-old son. Her second son was born shortly after her arrival. Her husband, Colin Lucas, remains in England, engaged in important war work.” [11]Lake, Talbot. Serve Vegetables, Soups To Conserve Says Expert. Huntingdon, Pennsylvania: Daily News. 9 March 1943. Page 8.

In any event, she was in Manhattan by early 1942. Her first job there was at the Longchamps Restaurant on Madison Avenue, fluting mushrooms in a window eight hours a day.

In March 1942, she gave cooking classes sponsored by the New York Junior League.

In the summer of 1942, she went to cook at a 1,000 acre dude ranch near Cody, Wyoming owned by wealthy Broadway actress Hope Williams (1897–1990).

In the fall of 1942, she opened the Le Petit Cordon Bleu cooking school and restaurant in New York, with herself as the Director, at 117 East 60th St., New York. It was the ground floor of a three-storey brownstone. Jeanne Schinto says that Cody Williams and a friend of Williams financed the restaurant. It specialized in omelets. [12]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 39.

From the opening of the school until the end of the war, owing to the occupation of Paris she was the only person in the world granting Cordon Bleu certification during that time period.

“The Cordon Bleu Cooking School, at 117 E. 60th Street. Mrs. Dione Lucas, who runs the school, has received a diploma, first class, of the Ecole du Cordon Bleu of Paris. Her methods of instruction are admirably reasonable and lead with sturdy logic from one fundamental principle of cookery to another. The school has morning and afternoon classes, during which the pupils cook but do not eat what they prepare, and an evening class ending up with a dinner at which the dishes cooked are served, eaten and discussed. Lessons are five dollars apiece, and there is a course of forty-eight lessons for $192. If you stay to eat your dinner, that’s $2.50 more.” [13]Sheila Hibben, Markets and Menus. The New Yorker, 3 February 1945, p. 63.

(Later, a Jesie Wilson would help her with the school, and in the late 1950s, she moved the restaurant and school to 3 East 52nd Street.)

Family separation

At the end of the war, Colin came to Manhattan to meet up with his family. He did some architectural consulting work for the British Council there. Dione’s career in America was taking off, but Colin didn’t see many possibilities for him.

In 1944, Mark, eleven at the time, went to England to live with Colin.

At the end of the 1940s, Dione and Colin separated. Colin became a successful architect in England working for London County Council in rebuilding London.

Start of Dione’s television career

At the end of 1947, Dione started a television show called “To The Queen’s Taste” (see Television section below.)

In addition to the television show, her restaurant and school continued to be a success. At her Cordon Bleu restaurant in New York, in 1950 she would make up to 200 omelets at noon hour. You could choose from sixteen different ones on the menu.

Her second TV show started in 1953 (see Television section below).

The 1950s was a time when home economics teachers and USDA Extension Agents across the country were teaching cooking as a science. Lucas, however, mocked that school of thought, and approached it as an art form:

“Where there was a strong lobby for the professionalization of cooking and propagation of the idea that cooking was a science in the 1950s, Lucas was firmly in the art camp. Her demeanor and attitude towards cooking went a long way toward removing cooking from the category of obligatory work altogether. While she ignored the art versus science debate on the surface, she mocked notions of precision instructing, for example, to add “52 ½ grains of salt” or “7 ¼ grains of cayenne pepper.” [14]Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own: The Paradox of Dione Lucas. City University of New York (CUNY) John Jay College. 2012. Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 27, no. 2 80 (2012): 1-23.

A television columnist quoted her as saying to an audience of Home Service Program participants, “If cooking becomes like housekeeping, like making beds, nothing good will come out, just something unpleasant.” [15]Crosby, John. Cooking in Front of a TV Camera. Portsmouth, Ohio: Portsmouth Times. 1 August 1949. page 20.

Early 1950s work in Bennington, Vermont

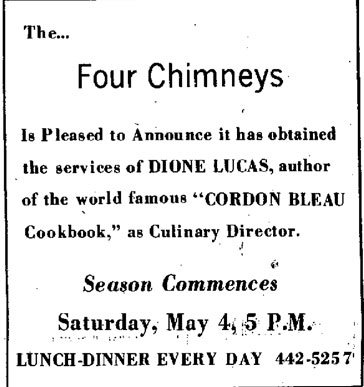

Sometime after 1953, she worked for Jimmy Rallis at the Four Chimneys Restaurant in Bennington, Vermont. [16]Rallis, Nancy, Stephen Rallis and Diane Conover. A tribute to Jimmy Rallis. Letter to the Editor. Bennington Banner. 11 May 2005.

In 1955, she gave a cooking demonstration on June 19th at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont.

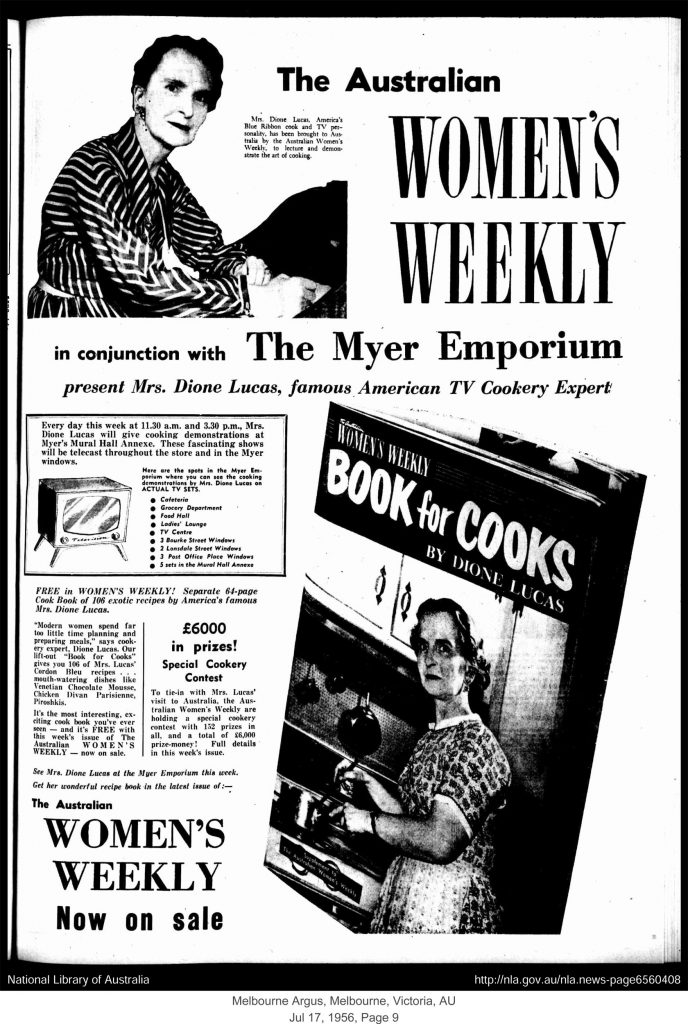

Dione Lucas’ Australian connections

In the mid-1950s, Lucas went to Australia during the summers and appeared on television programmes there.

“Mrs Dione Lucas, America’s Blue Ribbon cook and TV personality, has been brought to Australia by the Australian Women’s Weekly, to lecture and demonstrate the art of cooking.” [17]Advertisement in: The Argus. Melbourne, Australia. 17 July 1956. Page 9.

(Click for larger.)

In the 1960s, she added writing for the Australian Women’s Weekly to her list of chores.

This Australian video discusses Lucas’ presence in Australia:

The Egg Basket

In 1956, Dione opened a restaurant called the “Egg Basket” for Bloomingdale’s in New York on East Fifty-Seventh Street.

“When she opened an omelet restaurant in New York City called The Egg Basket, I think I was one of the first customers. The restaurant had a counter, where you could watch while Dione Lucas prepared omelets for everyone. I had the first stool, and I had the time of my life. She was a magician with omelets.” [18]Heatter, Maida. Maida Heatter’s Cakes. Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews McMeel Publishing. 2011. Page 75.

She was fanatical about her omelets. If waitresses hadn’t collected them to serve to the customers fast enough, she’d throw the omelets out. In references to her life, over and over again you will hear the omelets mentioned. She preferred aluminum omelet pans that were thick and free of pitting, and brightly polished. [19]Correspondence with David M. Blum, October 2013. On file with cooksinfo.com. Blum worked with Dion at the Dione Lucas Gourmet Center from 1967 – 1971.

She also became known for the single dessert she served at the restaurant, a chocolate roll.

The [Egg Basket] restaurant served only one dessert, Dione Lucas’ famous Chocolate Roll.” [20]Heatter, Maida. Maida Heatter’s Cakes. Page 75.

The Egg Basket restaurant was still in operation as of 1961. On 15th of December 1961, James Beard hosted a celebratory dinner for Julia Child at the Egg Basket, to celebrate the publication of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.”

“Dione Lucas had once run the Cordon Bleu’s school in London, but she didn’t strike us as especially organized, or sober. A few days before the party, the menu hadn’t been finalized and arrangements for the wine delivery had yet to be made. Paul and I made an appointment to discuss these details with Ms. Lucas, but when we arrived the Egg Basket was closed and dark. Tacked to the locked door was a note, saying something like “Terribly sorry to have missed you, my son is ill, very ill….” Hm. When Judith Jones had lunched at the restaurant two weeks earlier, Lucas had been missing due to a ‘migraine.'” [21]Julia Child. My Life in France. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. Page 259. [Ed: Reputedly Dione’s favourite tipple was half Guinness, half ginger beer.]

The Gingerman Restaurant

In 1963, Patrick O’Neal was acting in a play in New York based on the book “The Gingerman” by J.P. Donleavy. He, his wife Cynthia, and his brother Michael decided to open a restaurant of the same name.

The restaurant was at 51 W. 64th Street.

In late 1963 / early 1964, Patrick and Michael were waiting for their liquor licence to be approved before they opened. During that time, Michael decided to take a cooking course at Dione Lucas’s cooking school.

Lucas expressed interest in becoming the chef for his new restaurant, and they agreed. At the restaurant, there was a window into the kitchen so that customers could watch her at work.

Standard Brands

By 1960, she was endorsing products for other companies such as Standard Brands.

“One interesting meeting [Ed: in Chicago] was that of Standard Brands when they presented a “Seminar in Advanced Cookery.” The classroom was the Four Georges Room at the Ambassador West Hotel and the instructor was Dione Lucas, famed authority who has a well-deserved reputation as one of the outstanding teachers of fine cookery today.

From a kitchen setting with white brick walls, copper appliances and accent touches of bright emerald green, Mrs. Lucas presented a number of delectable dishes utilizing Standard Brands products. With Chase and Sanborn Coffee, she prepared a famous coffee drink known as Vienese [Ed: sic] Coffee Franz Josef and an Austrian Veal Roast that owes its goodness to a coffee-flavored sauce.

Two new Royal gelatins — watermelon-flavor and peach-flavor were introduced in a spectacular Austrian Jelly Tart that combines a rich pastry shell with vanilla cream filling and fruited jelly topping. For the filling, Mrs. Lucas used Royal Vanilla Pudding.” [22]Lewellyn, Hattie. They’re Cooking With Coffee. San Antonio, Texas: San Antonio Express. 1 October 1960.

Return to Bennington, Vermont

In April of 1968, she moved back up to Bennington, Vermont, as seen in the following advertisement from the Bennington Banner.

Dione Lucas Four Chimneys advertisement. Bennington, Vermont. 2 May 1968. Page 6.

There she could be closer to her sister, and to her son, Peter, who was living in North Bennington (Mark was living in England.) Her sister, Orea Pernel was a violinist and taught at Bennington College for several years. She can be heard playing with Isaac Stern on the CD “Pablo CASALS 1er Festival de Prades 1950.” Lucas once remarked of Orea that she loved tomatoes “in every form or shape.” [23]Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 7.

In September 1968, Dione switched to another Bennington restaurant called the Potters Yard Brasserie, working for David and Gloria Gil.

“The menu at the Potters Yard Brasserie features the dishes for which Mrs. Lucas is well-known. There are 10 varieties of omelets offered for lunch, ranging from “plain” to “red caviar” concocted from sour cream, chopped onions, strained hard boiled egg yokes and whites, and parsley. All omelets are served with salad and coffee or tea, and are priced from $2 to $3.25.” [24]Scribner, David. Cordon Bleu Chef Dione Lucas Opens ‘Brasserie’ Restaurant. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 8 November 1968. Page 14.

A listing for skiers later in the same paper called the restaurant “Expensive but worth it.” [25]Bennington Banner. 21 December 1968. Page 51.

Again, there was a window so people could watch her:

“I particularly remember the day my wife and I went to lunch at the Brasserie and happened to have our daughter Abbye, age one and a half, along. Mrs Lucas saw us through the glass window that separated the dining room from the kitchen, nodded hello, prepared the two lunches as ordered, then herself brought Abby something special: a perfect minute omelette [sic] bonne femme, exactly the shape of a whale and no more than three inches long.” [26]Clay, George R. Tribute to Mrs Lucas. Letter to the Editor. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 24 December 1971. Page 4.

She stayed with the Brasserie for only 9 months [27]Bennington Banner. Dione Lucas To Open School In Manhattan. Bennington, Vermont. 23 September 1969. Page 3. “Dione Lucas, who has cooked at the Four Chimneys and then for nine months operated the Brasserie Restaurant in the Bennington Potters yard here…”, and then returned to New York:

“Dione Lucas has been lured back from Bennington, Vt., where she was operating a restaurant, to East 51st Street, where she has a new Dione Lucas Store and Cooking Center. She limits her cooking classes to six or eight students, and has a waiting list of celebrities. The great lady is now 60, but wields her heavy omelet pan as if it were a table tennis paddle…” [28]Heimer, Mel. My New Nork. Naugatuck, Connecticut: Naugatuck Daily News. 11 May 1970. Page 10.

“Dione Lucas, for years the ultimate authority among cooking instructors, classic French style, has returned to the city and will be in charge of the Dione Lucas Cooking School on 51st Street as of Dec. 1. She will have special classes for “men only, career girls and for children. … “Mrs. Lucas will hold two-hour classes Monday through Friday for six-week periods, and there will be five different menu agendas for prospective students to choose from.” [29]Claiborne, Craig. New York Times. 23 September 1969.

“DIONE LUCAS, whose fame internationally as a cook began many years ago with her Cordon Bleu cooking school, has opened the Dione Lucas Store and Cook Center at 221 East 51st St. New York city, according to a New York Time’s article Thursday by Craig Claiborne.” [30]Rockwood, Agnes. Just Pokin’ Around. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 6 March 1970. Page 3.

The combined cooking school / store seems to have been the latest incarnation of a non Cordon Bleu Cooking School run by her. According to David Blum who worked in the store from 1967 to 1971, she got the cooking school space free of rent in exchange for lending her name to the store and above, which became a franchise owned by Hobi and then Bevis industries, with whom she’d also have a collaboration on knives (see below.) [31]Correspondence with David M. Blum, October 2013. On file with cooksinfo.com. Blum worked with Dion at the Dione Lucas Gourmet Center from 1967 – 1971.

After that at some point, classes were held at East 59th Street, and then under the name of the Gourmet Cooking School, at East 60th Street.

At one of those points, it seems, she held classes in the basement of a brownstone: “Some time later I considered myself extremely lucky to be able to attend cooking classes at Ms. Lucas’ cooking school in the basement of a brownstone in New York City. There were about seven people in each class, and everyone cooked — all at once. We were allowed to choose whatever we wanted to cook.” [32]Heatter, Maida. Maida Heatter’s Cakes. Page 75.

Death of Dione Lucas

Lucas’s last residence in New York was at 200 East 51st Street. Her sister Orea had moved to Ticino, Switzerland by then. [33]Obituary. Dione Lucas, culinary artisan, dies in London of pneumonia. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 20 December 1971. Page 22.

In 1970 and 1971, she had surgery for cancers.

In September 1971, she went back to London to live there for a while and to see her son, Mark. Sometime after arriving in England, she received cobalt radiotherapy for cancer.

She wrote to Gorman that she was not giving up and was determined to get back at work as soon as she could:

“I feel very lost at the moment; but as soon as I can get really going with the [provincial French cooking] book I feel all this will sort itself out.” [34]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 44.

She died in London of pneumonia shortly before Christmas 1971, aged 61, on Saturday, 18 December 1971. [35]”Dione Lucas, 62, internationally known gourmet cook… died Saturday of pneumonia in London… She had resided at 200 East 51st Street, New York City.” — Bennington Banner. Dione Lucas, culinary artisan, dies in London of pneumonia. Monday, 20 December 1971. Page 21.

Other Activity

Lucas founded the Dione Lucas line of knives, which some people are still using and still swear by.

They were made in conjunction with Bevis industries:

“Lucas invented the Gourmet Knives when the knife she was using proved an unsatisfactory de-fatting tool for her Supreme de Volaille. In frustration she created these knives with their excellent balance, molybdenum-alloy blades, and strong rosewood handles curved to fit the fingers. In 1974 four knives sold for $19.94, with a lifetime free-replacement guarantee.” [36]Stanley, Autumn. Mothers and daughters of invention. Rutgers University Press. 1995. Page 56.

Dione Lucas knives on ebay

The design of the knives seems to have been Japanese in inspiration:

“Lucas’ name was also made immortal in her collection of Japanese knives, which are made of molybdenum steel and have strangely squared off tips. You can still find some pieces on eBay.” [37]Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child.

At some point, she worked for the Heritage Village Restaurant in Southbury, Connecticut.

Legacy

Many popular cooking educators manage to both lead and connect with their audiences. Writer Kathleen Collins suggests that Lucas (as well as James Beard) did not manage that connection with their audience, and their times, in the way that Julia Child did, and that is why they are largely forgotten now, while Child is still revered in memory:

Unlike most of the home economics and women’s service programs on during the time period, Lucas prepared urbane dishes more likely to be served at dinner parties than at the weeknight family dinner table. In making mostly European food, she would often begin a suggested instruction with, “In France they….” Her European background and accent compounded the foreignness, an aspect that was at odds with the strong sense of American patriotism surging through the postwar, Cold War U.S. during the time she was on the air. French cuisine was still quite unusual to most people in the U.S., and while Lucas presented it frequently, it was not until Julia Child did so – at the same time that the Kennedys employed a French chef in the White House – that French cuisine began to present itself as a noticeable trend in the U.S. All of these factors made Lucas unusual in relation to her TV peers and in the media context… Both James Beard and Lucas were out of sync with their peers…

The many contradictions and contraventions personified by Lucas were not a hindrance to her popularity at the time of the program’s broadcast. They were, however, an obstacle to her place in the collective memory. Lucas is largely forgotten by time and, despite her television longevity, written out of the more cursory cooking show histories. Beard and Lucas did not fit with the times and therefore are not a functional part of a tidy story of U.S. cultural history, whereas Child was fully emblematic of her period and is recalled as a matter of course.” [38]Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 6, 16.

Another writer, Tamara Palmer, attributes her faded legacy to her personality:

“So with so much talent, success, and business savvy, why has Lucas’ name more or less faded from history? Again, a lot of it may come down to her chief difference from Julia Child. Lucas may have inspired a cult following with her technical skills, but her severe, humorless personality didn’t win her many mainstream fans—on or off screen. In 2011, some 40 years after Lucas died from pneumonia, Gastronomica ran a story called “Remembering Dione Lucas” that speaks of the “temper and moods” and “erratic behavior” that contributed to her being “actively dislikable.” It’s a persona that may have inspired respect but not much warmth (an unfair problem for a female cooking personality, especially half a century ago). Renowned cookbook author Paula Wolfert, who studied under Lucas and was for a time her assistant, has said, “Dione was a bitter woman, not warm and cuddly, like a mentor should be.” Food writer David Kamp, writing in his book United States Of Arugula, described Lucas as “small, stocky, and dour, with her hair pulled back tightly like a suffragette’s.” [39]Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child.

Jeanne Schinto writes that “her personality was at odds with the whole idea of mass appeal.” [40]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 35.

Schinto says that it’s unfortunate that writers such as Kathleen Collins have given “space to unquestioned criticisms of Dione’s ‘actively dislikeable‘ off-screen personality.” [41]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 34.

There have been allegations of alcoholism and drug addiction, as well as money problems. There were also intimations that her son Peter was mentally impaired. Allegations and insinuations have appeared in books such as Appetite for Life: The Biography of Julia Child by Noel Riley, My Life in France by Julia Child with Alex Prud’homme, and Fitch, Love and Kisses, and a Halo of Truffles: Letters to Helen Evans Brown by James Beard. Some were even repeated publicly by Julia Child at a meeting of Les Dames d’Escoffier sometime around 1993.

This prompted food publicist Marian Gorman to write to Child to refute the insinuations. Gorman said that Dione suffered from migraines, which may have led to her leaning heavily on prescription drugs to manage them, and that Peter was in full charge of his mental faculties. Child was mortified and apologized profusely.

Lucas’ son Mark remembers that in order to keep all the various balls in the air needed to keep the various businesses going and support Peter, Lucas often simply went several days without sleep. [42]“…often kept working through several days and nights.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 40.

At this point, it’s not unreasonable to wonder if so much attention would be paid to whether a man in a similar position would be so analysed for being “likeble” or not. But then, in the world of cooking, the temperament of a cook or a chef whether male or female seems to always be analyzed in the way it is in almost no other endeavour, ever since the days when Francois Vatel committed suicide over a supposed missing fish delivery.

A scholarship fund, the “Dione Lucas Scholarship Fund” was set up in her memory at the Culinary Institute of America in New Haven, Connecticut. It is not known if the fund is still extant.

At her death, her papers and files came to her sons. Sometime in the 1970s, they in turn gave them to Marion Gorman, the food publicist who had known Lucas since the early 1960s. Gorman used the papers to finish Lucas’ last cookbook — she needed personal snippets to put in between the recipes.

In the 1990s, at the urging of Julia Child, Gorman donated the papers to the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University. [43]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 35.

Jeanne Schinto, who has been through the files, cautions future researchers that the files may contain no great insights into Lucas: “the files contain only a few pages written by Dione herself. Two are letters written to Gorman (and one seems retyped by the recipient); another is a single halfpage of a personal reminiscence by Dione about Broadway producer Billy Rose.”

Dione Lucas and James Beard

Lucas and Beard were rivals in a way, fighting for the attention of what was then a small (though growing) circle of foodies in New York City.

Jessamyn Neuhas feels that, at first in the 1940s when they each had shows on televison, Beard did not like Lucas at all.

“Beard actively disliked his best-known competitor on the air: Dione Lucas. … Beard … developed his own American-based cooking style, (while) Lucas adhered to the rules of the Ecole due Cordon Bleu in Paris….” [44]Neuhas, Jessamyn. Manly meals and mom’s home cooking: cookbooks and gender in modern America. JHU Press. 2003. Page 183.

In the 1950s, Beard was a dinner guest several times in Lucas’ apartment. He said she made people uneasy by not eating herself, but instead watching every bite people took. At a dinner party in June 1953, he said she fell asleep in the living room. In December of the same year, Lucas proposed a collaboration between the two running a restaurant and giving classes, which Beard pondered because of the potential frisson of horror and suspense that a collaboration between the two rivals might generate. It never happened, though.

Overtime, his thoughts about her softened further. After another dinner party at her place in February 1961, he wrote that he was fond of her and envious of how she worked with her hands, but that all her dishes used too much cream. [45]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 41.

In December 1961, presumably to help support her, Beard chose Lucas’s Egg Basket restaurant in which to host a dinner for Julia Child to celebrate the publication of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.”

Books

“The Cordon Bleu Cookbook in particular has numerous ambitious recipes that would be great for some sort of Old World-themed dinner party, including more than two dozen ways to prepare sole, copious Coquille St. Jacques remixes, and even salmon pudding. The chapter on eggs is where the most timeless knowledge is concentrated, and where aspiring masters can hone their skills. Lucas’ “oeufs en surprise” (poached eggs in cheese omelet), for example, borders on a party trick in its combination of two classic techniques in a way that was, culinarily speaking, well ahead of its time.” [46]Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child.

- 1936. Au Petit Cordon Bleu: an array of recipes from the ‘École du Petit cordon bleu,’ 29 Sloane Street, London. With Rosemary Hume.

- 1944. The Cordon Bleu Cook Book. Little, Brown and Company, Boston. Dedicated to Rosemary Hume.

- 1955. The Dione Lucas Meat and Poultry Cook Book Boston, MA: Little Brown (with Anne Roe Robbins.) 324 pages. Illustrated.

- 1960. Good Cooking. Sydney: Australian Consolidated Press. 64 pages. Illustrated.

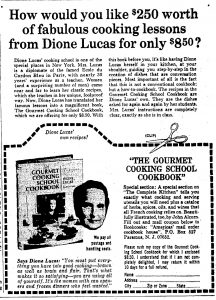

- 1964. The Gourmet Cooking School Cookbook. New York: Bernard Geis Associates.

- 1973. The Dione Lucas Book of French Cooking (published post-humously by co-author Marion Gorman.)

- 1977. The Dione Lucas Book of Natural French Cooking (written by Marion Gorman & her husband Felipe Alba.)

- 1982. Gourmet Cooking School Cookbook (written by Darlene Geis.)

Television

To The Queen’s Taste

The “To The Queen’s Taste” series was Dione’s first foray onto television.

It was directed by Frances Buss Buch (1917-2010), who was CBS’s first female director. [47]”[Buss] returned to CBS as an assistant director in 1944, and a year later made a television director. [She] now directs two shows which keep her busy all week — “Vanity Fair” the sight-and-sound women’s magazine edited by Dorothy Doan, and “Dione Lucas Cooking Program.” — Regarding a distaff director. New York Times. 3 April 1949. Page X9.

In 1940s America, “Queen’s Taste”, and “To a Queen’s Taste” were popular phrases used in advertising of household goods, anything from bed mattresses to frying pans.

Many sources give the series a 1948 start date. But Kathleen Collins, who wrote a short analysis of the show, gives it a 1947 start date: “…her show was first broadcast in 1947”. [48]Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 4. Jeanne Schinto says “her television debut one evening in the New York City area in December, 1947.” [49]Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 34.

At the start, the show was broadcast live from an actual kitchen. “The Dione Lucas Show was shot for at least part of its run in the basement of her restaurant across the street from her New York City apartment.” [50]Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 10.

By July 1948, it had been moved to a studio kitchen at CBS itself. “Mrs Dione Lucas will do her WCBS-TV cooking series from an ultra-modern kitchen in the CBS studios, starting tomorrow at 8:05 pm.” [51]Clark, Rocky. Listening Post column. Bridgeport, Connecticut: The Bridgeport Telegram. 11 July 1948. Page 29.

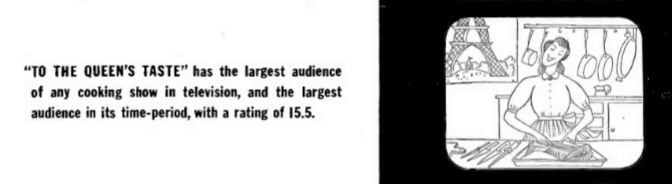

By the fall of 1948, the program was ranked highly by agencies which tracked TV ratings. “TO THE QUEEN’S TASTE” has the largest audience of any cooking show in television, and the largest audience in its time-period, with a rating of 15.5.” [52]Broadcasting Magazine. 27 September 1948. Washington, DC: Broadcasting Publications. Page 6.

Broadcasting Magazine. 27 September 1948.

When the series first started (in 1947 or 1948), it had a 15 minute timeslot starting at 8:05 pm: “CBS Television began regular network operations Monday, May 3, 1948 ….. at 8:05 [pm], the last network show of the day, a cooking show with Dione Lucas called “To The Queen’s Taste,” aired for fifteen minutes as a remote from Bloomingdales.” [53]Ellerbee, Bobby. The History of CBS New York Television Studios: 1937-1965. 2015. Accessed July 2019 from https://eyesofageneration.com/.

The show was broadcast live, and taped: “To the Queen’s Taste aired live in New York broadcast by WCBS-TV, a television station, and was recorded in kinescope.” [54]Swanson, Victor E. Television History and Trivia. Cheboygan, Michigan. 10 April 2017. Accessed July 2019 at http://www.hologlobepress.com/that156.htm

By the 1949 – 1950 season, it was weekly on Thursday at 7 pm EST. At some point, it was lengthened from 15 minutes to 30 minutes. This allowed Lucas to tackle two, sometimes three dishes in an episode. Radio and television reviewer John Crosby wrote:

“Mrs. Lucas usually prepares two dishes — a meat course, say, and a dessert — in one half-hour program, and many of these are enormously complicated dishes. She hates any form of cheating and insists on performing all possible steps right in front of the camera. If the recipe calls for a boned-chicken, she bones one, keeping up a steady stream of ad lib chatter as she does it…

Her worst experience came during the early days of the show. Mrs. Lucas was demonstrating the preparation of a hot chocolate souffle. After going through the mixing stages, she reached for a pre-cooked souffle to show how it looked when finished: Without her knowledge, a CBS technician had pulled the oven plug and the souffle was completely uncooked. When Mrs. Lucas pulled the paper off, chocolate spurted in all directions. Mrs. Lucas, paralyzed with horror, kept right on chatting about its glamorous appearance while the souffle dissolved, before her and everybody else’s eyes. The show drew to a close without further explanation…

Not all [her] information is practical. Once she explained that the best way to locate truffles in a forest, was to follow a pig: “Pigs love truffles. Pregnant pigs, especially,” she added dreamily. “Pregnant pigs adore truffles.” [55]Crosby, John. Cooking in Front of a TV Camera. Portsmouth, Ohio: Portsmouth Times. 1 August 1949. page 20.

James Beard (who was on NBC) didn’t like her in the 1940s:

“Beard actively disliked his best-known competitor on the air: Dione Lucas. Lucas ran a cooking school and restaurant in New York, and her CBS program began shortly after Beard began his regular NBC appearances. In contrast to Beard, who developed his own American-based cooking style, Lucas adhered to the rules of the Ecole due Cordon Bleu in Paris….” [56]Neuhas, Jessamyn. Manly meals and mom’s home cooking: cookbooks and gender in modern America. JHU Press. 2003. Page 183.

Luca’s first show even has modern day detractors:

“It’s unclear as to whether or not the show was a start-to-finish study in preparing specific recipes; there don’t seem to be any surviving archival copies of her programs. Those who do recall her personally and on screen noted that she was generally of a dour demeanour, with apparently no more charisma on screen than [James] Beard. [David] Kamp notes that “she was small, stocky, and dour, with her hair pulled back tightly like a suffragette’s…” [57]Eanes, Ryan Scott. From Stovetop to Screen: A Cultural History of Food Television. Thesis for the Master of Arts in Media Studies. The New School. 2008. Page 12.

Interview with Frances Buss Buch on Lucas’ “The Queen’s Taste”

In 2009, televisionacademy.com conducted a wide-ranging interview with Lucas’ director, Frances Buss Buch, when Buch was 91.

Here are transcripts of the two portions of that interview that address “To The Queen’s Taste”. Some standard, repetitive patterns of speech were tidied up for brevity.

Excerpt One

Source: Frances Buss Buch Interview, Part 2 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com. Interview conducted by Karen Herman. Youtube. Posted 30 September 2009. Time 23:54 to 31:00

Q: Do you think that being a woman director influenced what shows you were placed on?

Oh I’m sure. The Dione Lucas show which was called — I think Tony Meyer was a little bit of a snob — they never thought to call it the The Dione Lucas Show, they called it ‘To the Queen’s Taste’. Well Dione was an English woman with a Greek name, and I guess she was so glad to get the show that she didn’t protest about what they called it. But she was a marvellous chef and interesting to listen to, very formal in her approach, no waving around of pans like Julia Child, she didn’t have much humour but she was a grand chef. She previously had been doing demonstrations in front of women on behalf of the gas company for example, or maybe the electricity, no I’m sure it was the gas company because she cooked only with gas. I learned that from her and have never had an electric range in my life. Although I’d love to have an electric oven now and a gas range. But she did fascinating things and that really was marvellous fun. And then of course if she was doing elegant desserts, we all got to eat it afterwards.

Q: Where was the show done?

Originally it was done in the kitchen of her restaurant, well the kitchen of her brownstone, I think it was in 60th and 61st street, between Park and Lexington. She had an omelet restaurant, a luncheon restaurant only and it only served omelets, many different kinds of omelets, and she made them all herself. She had one helper, her name was Margaret, she was an Irish girl, and I often felt sorry for her because Dione really beat on her. She had a kitchen downstairs in that building and that is where the original programmes were done because the programme began during that hiatus when we were not in the studio. How they ever got the cameras down there, I don’t remember. That wasn’t my problem. But it was pretty tight. I think she gave classes, very small classes down there in her kitchen.

Q: Who were her clientele for those classes?

Well I think that people like Dorothy Rogers, Richard Rogers’ wife, studied with her and maybe Mrs [Bennett Serv?] as well, these were elegant women with successful husbands and they passed the word around and friends of theirs went to Dione’s classes. Dione had all the techniques that she learned at the Cordon Bleu. You’d keep worrying she was going to chop her fingers off she went so fast. I never learned that but I learned how to make omelets and still do, I make one for myself every Sunday for lunch. But now of course we have no stick pans, which was not the case back then, and Dione was very particular that you never washed your omelet pan, you just wiped it out with a clean towel, or a paper towel, because you would spoil it, it would stick after that. I still have my original omelet pan that I bought back when I was working with Dione, however you can’t make omelets in it anymore.

Q: What were some of the other specialties that she showcased on the show?

Her most dramatic specialty was the strudel. She loved to make the strudel. She would throw the dough down. This is kind of like Julia Child, making the dough was part of the fun of it. Then with the strudel you have to pull it out, you start with a ball of dough, and then you pull it out until it’s so big that it completely covers the table, which is 30 inches by 60 inches or something like that, and she would pull it out until, as she said, you can read the New York Herald Tribune through it. And it was the Tribune. She was a Republican. She didn’t ever mention the New York Times. And this I think related to the people who were her clients, they were Republicans, which is not surprising.

Excerpt Two

Source: Frances Buss Buch Interview, Part 3 of 5 – TelevisionAcademy.com. Interview conducted by Karen Herman. Youtube. Posted 30 September 2009. Time 2:47 to 12:10.

Q: How did Lucas come across on camera?

Very well I think. She was quite formal in her speaking and I taught her how to hold things and where to hold them for me, so that I could get a close-up of what she was talking about… I wanted to show what it was she was talking about…. She had been accustomed to doing demonstrations for a roomful of women, an audience of women, for the demonstrations for the gas company, but nobody got down really into her hands and how she was manoeuvring things under those circumstances, and TV, that was what TV was for, to see what she was doing…

Q: What did you teach her specifically, what kind of movements?

I taught her how to hold things. She was accustomed to sort of waving things around and she couldn’t do that on television, at least I told her she shouldn’t. She learned what the area was that I could cover with cameras and she learned to point things, position them, so that the camera could see them and this was new for her, and she had to learn that. I think it stood her in good stead for the rest of her life, as long as she was doing television. After the program on CBS, she went over to ABC and did a Dione Lucas program on ABC, and I think she learned a lot of her technique on our program.

Q: Did she actually cook any food live?

Oh yes, all the time. She baked cakes. Of course, she had to fake it. She would prepare it, and bring out something that had been baked ahead. What they do on cooking programs now is marvellous. Of course they have a staff in the back somewhere who prepares all this in advance for the performer. All Dione had was Margaret, Margaret Sullivan was her name, no relation to the actress by that name. She did the shopping, and if Margaret had brought Dione for example a grapefruit that had seeds in it, she would really be eaten out afterwards. One of the things Dione did was to section a grapefruit. Not the way we do it today, today they peel a grapefruit that way, slicing down, Dione would do it with a chef’s knife, working toward her thumb, and you were always a little nervous about that, and I learned to do that, and did grapefruits that way myself, for years. But now since I’ve watched chefs on the air now do it a different way, I’ve changed the way I do it. I never cut myself, but I picked up many of her mannerisms.

Q: Were there ever any accidents on the show?

I don’t remember — you know, the famous soufflé falling and that kind of thing, well Julia Child went through that. Dione did make soufflés, and she made beautiful constructions with brioche and [croquembuche]. She made lovely desserts. Not pies as I recall, but. Of course the strudel then was filled with apple, which had been sautéed in butter. She used a lot of butter. I have her cookbook [in which she wrote a nice note of dedication to me].

Q: Had you been interested in cooking before?

Not really. [Buch discusses her food while growing up]

Q: Talking about the set, when you first started the show, it was at her brownstone, but then did it move to the studio, once the studio was finished?

Yes, and they built a studio kitchen for her in that new studio. It was an attractive kitchen with a table with a marble top for her to work behind. I don’t remember much about it other than that. It was very nice and she was pleased.

Q: Who sponsored the show?

She never got a sponsor.

Q: Did people ever write in for recipes?

I don’t think so. She was a demonstrator. It was not an interactive show. You could write it down as you went. She gave you all the information if you choose to write it, but I don’t remember that there was an audience by mail. I may be mistaken about that. [Editor: Her memory does seem to have been incorrect. A 1949 radio & television columnist writes, “Mrs Lucas’s program, for example, draws from 2,000 to 4,000 letters a week, a figure that compares favorably with any radio program on the air to say nothing to television cooking expert both by seniority and also by sheer ability… Just keep your eyes on the screen, girls, and write CBS after the show. They’ll send you the recipes… Housewives within reach of Mrs Lucas’ program have proved to be an intrepid lot. They tackle even the toughest of her recipes and then write in to ask what they did wrong when things don’t turn out right.” [58]Crosby, John. Cooking in Front of a TV Camera. Portsmouth, Ohio: Portsmouth Times. 1 August 1949. page 20.

Cooking with Dione Lucas

Her second television series, “Cooking with Dione Lucas”, started in 1953. Produced through Manhattan channel WPIX, it was a ½ hour long programme called “The Dione Lucas Cooking Show.” It was syndicated out to close to 60 other cities. Many channels ran it as a morning or afternoon show.

One of the sponsors was Caloric Ranges. She endorsed them in ads, and they even released a model named after her, which she used on her TV show. Sponsors varied by channel & state — on WFBM, Indiana, it was the Indiana Gas and Water company.

The series ran until about 1956.

Additional television work

In the early 1950s, Lucas did live programs for WJZ-TV, which were broadcast on Mondays in 1951, and on Monday, Wednesday and Friday in 1952. [59]Swanson, Victor E. Television History and Trivia

In the mid 1950s, she did some television shows promoting gas cooking. Some of these were paid for by Robershaw-Fulton Controls Co.. These particular shows were distributed free to gas companies throughout the US, which could in turn buy time from their local TV stations to put the programmes on the air.

Another set of programmes was produced by Arthur H. Modell Television Co.

In 1958 / 1959, Dione Lucas’s Gourmet Club aired weekly on Tuesdays on WPIX-TV (New York). The Brooklyn Gas Company was involved in sponsoring the series. [60]Swanson, Victor E. Television History and Trivia. Cheboygan, Michigan. 10 April 2017. Accessed July 2019 at http://www.hologlobepress.com/that156.htm

Dione Lucas’ screen persona

Lucas’ screen persona is now critiqued as being dour, rigid, formal.

For starters, it’s useful to remember that in the 1950s, television educators were trying to establish themselves as serious educators worthy of note. Joviality, wit and horseplay may not have been either expected or welcomed by their audiences.

Additionally, Kathleen Collins, who has made a study of Lucas’ television shows, notes that most of her television shows were sponsored by gas companies, and that this sponsorship may have influenced the personality she allowed herself to project on screen.

“…who confined and defined her persona? Was it Dione Lucas herself or another entity? While she was seen as a television cooking teacher, she had an equally, if not more important role as a promotional conduit and saleswoman. Despite her show’s eponymous title, it was not a vehicle to promote Dione Lucas but one to promote the appliances and utilities that she used. Text accompanying the show’s introduction read: “To encourage the American housewife to enhance one of her most creative talents, by bringing glamour to the dinner table through artistry in the kitchen with the aid of GAS—the Modern Cooking Fuel.” Lucas began every program not by introducing herself (not only did she never eat, but she never uttered her own name on screen) but with “How do you do? Welcome to my beautiful Caloric gas kitchen.” Lucas was at the service of the appliance, not the reverse (as, one might argue, is true in real home kitchens).

Acting as a promoter/spokesperson, then, is added to the list of required tele-skills of a cooking show host. While this was true of her peers and to a much lesser degree her successors, Lucas took the role to a masterful level: in one episode, she holds a print ad for a Caloric gas range under a piece of an expertly stretched, transparently thin section of strudel dough and reads it aloud. In other cooking shows, the specter of pleasing or appeasing one’s family was ever-present; in The Dione Lucas Show, the overseers were the gas companies and Caloric. The show was hers in name only….

She never says “stove” but is always careful to say “gas range” and “gas refrigerator.” … Indeed, the gas range was omnipresent to the point of becoming a major character in the show. The camera zoomed in and paused on close-ups of the burner controls and range top regularly. It served alternately as Lucas’ boss, sidekick, and icon, and Lucas consistently interacted with and praised her co-performer. “I don’t know what you think, Mr. Caloric Gas range, but I think it’s a pretty beautiful apple pie, and I think you’ll agree with me.” [61]Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 12.

Literature & Lore

“Undisputed monarch of gourmet cooking in America…” — Cannon, Poppy. Lucas Omelet Souffle. Alton Evening Telegraph. 14 January 1965. Page 22.

“Dione Lucas has long been the high priestess of haute cuisine in New York…” — Claiborne, Craig. Take Pride in Cuisine. New York Times News Service. Appearing in: San Antonio Express and News. san Antonio, Texas. 21 January 1965. Page 58.

“It’s best to cook a strudel when you feel mean. The beast stands or falls on how hard you beat it. If you beat the dough 99 times, you will have a fair strudel. If you beat it 100 times, you will have a good strudel. But if you beat it 101 times, you will have a superb strudel.” — Dione Lucas.

Language Notes

Dione pronounced her name “dee-OH-nee” (like “baloney” except “dee-ohney”.)

Further research sources

Papers of Dione Lucas, ca.1930-1995. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

Sources

Angelica, Gibbs. With Palette Knife and Skillet. The New Yorker. 28 May 1949. Page 34.

Bennington’s Social Activities column. Kitchen Display To Be Featured By French Cook. Bennington, Vermont: The Bennington Evening Banner. 4 June 1955. Page 6.

Burros, Marian. In Boston, Pilgrims’ Food (With a Touch of Paris). New York: New York Times. 27 January 1988.

Crosby, John. Cooking in Front of a TV Camera. Portsmouth, Ohio: Portsmouth Times. 1 August 1949. page 20.

Dugas, Gaile. Blue Ribbon Cook Says Good Food Takes Time and Effort. Lima, Ohio: The Lima News. 28 March 1950. Page 13.

Fussell, Betty and Mary Frances Kenndy Fisher. Masters of American Cookery. University of Nebraska Press, 2005. Page 57.

Grodinsky, Peggy. Food for thought: New book illuminates lives of those who influenced the way we eat. Houston, Texas: The Houston Chronicle. 21 March 2006.

Lowry, Cynthia. Cooking Of Gourmet Dishes For Video Requires Expert. Fresno, California: The Fresno Bee Republican. 26 December 1948. Page 8.

Paddleford, Clementine. “Cook Makes an Art of an Omelet.” New York Herald Tribune. 11 Feb 1950.

Rose, Ellen Cronan. The Brasserie: Gay, Casual And, Oh, Those Quenelles! Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 11 July 1970.

Sharp, Dennis and Sally Rendel. Connell Ward & Lucas: Modern movement architects in England 1929-1939.

Time Magazine. Cooking for the Camera. 30 May 1955.

Time Magazine. Everyone’s in the kitchen. 25 November 1966.

Vassar, Mark. Lucas, Dione, 1909-1971. Papers of Dione Lucas, ca.1930-1995: A Finding Aid. Retrieved October 2013 from https://hollisarchives.lib.harvard.edu/repositories/8/resources/6004

Wendler, Adelaide. International Culinary Expert at Home in Improvised Kitchen. High Point, North Carolina: The High Point Enterprise. 10 November 1960. Page 13.

References

| ↑1 | ”Many accounts, including a frequently quoted 1949 profile of Dione published in the New Yorker, say Dione Narone Margaris Wilson was born in Venice in 1909. While the year is correct, the place isn’t. “There’s been some publicity romancing about this one,” Mark Lucas says, “but it was Kent, England, where the Wilsons had their home and Henry Wilson, Dione’s father, had his studios.” Actually, though, as Mark discovered when he located the argument settler — his mother’s birth certificate — she was born in Kensington.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. University of California Press: Gastronomica , Vol. 11, No. 4 (Winter 2011). Page 36. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/gfc.2012.11.4.34. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”Catherine Baschet, with the publicity department at Le Cordon Bleu confirmed to Jeanne Schinto “that the often repeated idea that Dione was the school’s first female graduate is incorrect ‘for sure.'” But she did “confirm that a second young British woman, Rosemary Hume (1907–1984), studied at Cordon Bleu with Dione…” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 37. |

| ↑3 | Scribner, David. Cordon Bleu Chef Dione Lucas Opens ‘Brasserie’ Restaurant. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 8 November 1968. Page 14. |

| ↑4 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 34. |

| ↑5 | “I do not believe Rosemary Hume returned to Paris for further training in 1933 … [and] it seems unlikely that Dione had the time or inclination for a return visit of her own that year.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 38. |

| ↑6 | History of our school | Le Cordon Bleu London. Accessed August 2019 at https://www.cordonbleu.edu/london/our-story/en |

| ↑7 | ”In 1937–1938, Colin designed another restaurant for her, Au Petit Potager, on Wigmore Street. It never opened.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 49. |

| ↑8 | Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child. 14 December 2016. Chicago, Illinois: A.V. Club. Accessed July 2019 at https://tv.avclub.com/the-mother-of-all-celebrity-chefs-wasn-t-julia-child-1798255508 |

| ↑9 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 39. |

| ↑10 | Dugas, Gaile. Blue Ribbon Cook Says Good Food Takes Time and Effort. Lima, Ohio: The Lima News. 28 March 1950. Page 13. |

| ↑11 | Lake, Talbot. Serve Vegetables, Soups To Conserve Says Expert. Huntingdon, Pennsylvania: Daily News. 9 March 1943. Page 8. |

| ↑12 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 39. |

| ↑13 | Sheila Hibben, Markets and Menus. The New Yorker, 3 February 1945, p. 63. |

| ↑14 | Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own: The Paradox of Dione Lucas. City University of New York (CUNY) John Jay College. 2012. Camera Obscura: Feminism, Culture, and Media Studies 27, no. 2 80 (2012): 1-23. |

| ↑15 | Crosby, John. Cooking in Front of a TV Camera. Portsmouth, Ohio: Portsmouth Times. 1 August 1949. page 20. |

| ↑16 | Rallis, Nancy, Stephen Rallis and Diane Conover. A tribute to Jimmy Rallis. Letter to the Editor. Bennington Banner. 11 May 2005. |

| ↑17 | Advertisement in: The Argus. Melbourne, Australia. 17 July 1956. Page 9. |

| ↑18 | Heatter, Maida. Maida Heatter’s Cakes. Kansas City, Missouri: Andrews McMeel Publishing. 2011. Page 75. |

| ↑19 | Correspondence with David M. Blum, October 2013. On file with cooksinfo.com. Blum worked with Dion at the Dione Lucas Gourmet Center from 1967 – 1971. |

| ↑20 | Heatter, Maida. Maida Heatter’s Cakes. Page 75. |

| ↑21 | Julia Child. My Life in France. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. Page 259. [Ed: Reputedly Dione’s favourite tipple was half Guinness, half ginger beer.] |

| ↑22 | Lewellyn, Hattie. They’re Cooking With Coffee. San Antonio, Texas: San Antonio Express. 1 October 1960. |

| ↑23 | Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 7. |

| ↑24 | Scribner, David. Cordon Bleu Chef Dione Lucas Opens ‘Brasserie’ Restaurant. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 8 November 1968. Page 14. |

| ↑25 | Bennington Banner. 21 December 1968. Page 51. |

| ↑26 | Clay, George R. Tribute to Mrs Lucas. Letter to the Editor. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 24 December 1971. Page 4. |

| ↑27 | Bennington Banner. Dione Lucas To Open School In Manhattan. Bennington, Vermont. 23 September 1969. Page 3. “Dione Lucas, who has cooked at the Four Chimneys and then for nine months operated the Brasserie Restaurant in the Bennington Potters yard here…” |

| ↑28 | Heimer, Mel. My New Nork. Naugatuck, Connecticut: Naugatuck Daily News. 11 May 1970. Page 10. |

| ↑29 | Claiborne, Craig. New York Times. 23 September 1969. |

| ↑30 | Rockwood, Agnes. Just Pokin’ Around. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 6 March 1970. Page 3. |

| ↑31 | Correspondence with David M. Blum, October 2013. On file with cooksinfo.com. Blum worked with Dion at the Dione Lucas Gourmet Center from 1967 – 1971. |

| ↑32 | Heatter, Maida. Maida Heatter’s Cakes. Page 75. |

| ↑33 | Obituary. Dione Lucas, culinary artisan, dies in London of pneumonia. Bennington, Vermont: Bennington Banner. 20 December 1971. Page 22. |

| ↑34 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 44. |

| ↑35 | ”Dione Lucas, 62, internationally known gourmet cook… died Saturday of pneumonia in London… She had resided at 200 East 51st Street, New York City.” — Bennington Banner. Dione Lucas, culinary artisan, dies in London of pneumonia. Monday, 20 December 1971. Page 21. |

| ↑36 | Stanley, Autumn. Mothers and daughters of invention. Rutgers University Press. 1995. Page 56. |

| ↑37 | Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child. |

| ↑38 | Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 6, 16. |

| ↑39 | Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child. |

| ↑40 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 35. |

| ↑41 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 34. |

| ↑42 | “…often kept working through several days and nights.” — Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 40. |

| ↑43 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 35. |

| ↑44 | Neuhas, Jessamyn. Manly meals and mom’s home cooking: cookbooks and gender in modern America. JHU Press. 2003. Page 183. |

| ↑45 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 41. |

| ↑46 | Palmer, Tamara. The mother of all celebrity chefs wasn’t Julia Child. |

| ↑47 | ”[Buss] returned to CBS as an assistant director in 1944, and a year later made a television director. [She] now directs two shows which keep her busy all week — “Vanity Fair” the sight-and-sound women’s magazine edited by Dorothy Doan, and “Dione Lucas Cooking Program.” — Regarding a distaff director. New York Times. 3 April 1949. Page X9. |

| ↑48 | Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 4. |

| ↑49 | Schinto, Jeanne. Remembering Dione Lucas. Page 34. |

| ↑50 | Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 10. |

| ↑51 | Clark, Rocky. Listening Post column. Bridgeport, Connecticut: The Bridgeport Telegram. 11 July 1948. Page 29. |

| ↑52 | Broadcasting Magazine. 27 September 1948. Washington, DC: Broadcasting Publications. Page 6. |

| ↑53 | Ellerbee, Bobby. The History of CBS New York Television Studios: 1937-1965. 2015. Accessed July 2019 from https://eyesofageneration.com/. |

| ↑54 | Swanson, Victor E. Television History and Trivia. Cheboygan, Michigan. 10 April 2017. Accessed July 2019 at http://www.hologlobepress.com/that156.htm |

| ↑55 | Crosby, John. Cooking in Front of a TV Camera. Portsmouth, Ohio: Portsmouth Times. 1 August 1949. page 20. |

| ↑56 | Neuhas, Jessamyn. Manly meals and mom’s home cooking: cookbooks and gender in modern America. JHU Press. 2003. Page 183. |

| ↑57 | Eanes, Ryan Scott. From Stovetop to Screen: A Cultural History of Food Television. Thesis for the Master of Arts in Media Studies. The New School. 2008. Page 12. |

| ↑58 | Crosby, John. Cooking in Front of a TV Camera. Portsmouth, Ohio: Portsmouth Times. 1 August 1949. page 20. |

| ↑59 | Swanson, Victor E. Television History and Trivia |

| ↑60 | Swanson, Victor E. Television History and Trivia. Cheboygan, Michigan. 10 April 2017. Accessed July 2019 at http://www.hologlobepress.com/that156.htm |

| ↑61 | Collins, Kathleen. A Kitchen of One’s Own. Page 12. |