Victorian Kitchen. Helena / flickr / 2015 / CC BY 2.0

Eliza Acton was the author of two popular 19th century cookbooks. She was interested in nutrition, and was also a Victorian social reformer who corresponded with Charles Dickens. She was so popular and influential that many people plagiarized parts of her books. [1]”When the famous Mrs Isabella Beeton decided to publish her iconic Book Of Household Management she became a shameless plagiarist, and the writer she pillaged most blatantly was her predecessor Eliza Acton, a Victorian spinster whose Modern Cookery For Private Families, published in 1845, was the first to set out ingredients, quantities and timings in the methodical format we expect today. Except she gave method first, then ingredients – Mrs Beeton’s innovation was to turn this round.” The First Star Cooks. London, England: The Daily Mail. 18 May 2019.

A note to modern-day cooks from the UK: if you are cooking from her recipes with her measurements, one of her biographers, Sheila Hardy, cautions: “It is worth noting that in her day, a pint was the equivalent to 16 fluid ounces rather than 20 as now.” [2]Preface. Hardy, Sheila. The Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Stroud, England: The History Press. 2011.. (The Americans kept the 16 oz. pint; the English moved to a 20 oz. one.)

Early years

Eliza Acton was born 17th April 1799 in Battle, East Sussex, England; she died 13th February 1859 in Hampstead, London, England.

Her parents were John Alton and Elizabeth Mercer. [3]Ray, Elizabeth. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2004. John and Elizabeth would have six girls and three boys in all. [4]”Eliza was born at Battle on 17 April 1799, being baptised at St Mary’s on the next 5 June. Her father was John, born at Hastings in 1775, and her mother Elizabeth Mercer of East Farleigh in Kent; John’s father was Joseph, a major presence at Hastings and elsewhere nearby, who had married Elizabeth Slatter of Battle. The Slatters were well-known as tradesmen and minor property owners in the town. Joseph’s brother in law George was a grocer who also sold china and wines and spirits; George’s brother was a butcher.” — Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. Battleford District Historical Society (BDHS) August 2017. Accessed August 2019.

In 1800, when Eliza was one year old, John moved the family to Ipswich, Suffolk. All Eliza’s other sisters and brothers would be born there. In Ipswich, John worked as a managing clerk for Trotman, Halliday & Studd, a brewery business. [5]Glyde, John. The New Suffolk Garland. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co. 1866. Page 376.

“John is in the records as a brewer, though not at Battle; and his entry to that work was through general, and in particular financial, management. This developed after he and his family arrived at Ipswich in 1800 where he became manager of the local brewer Trotman, Halliday and Studd. The records suggest that this was not a puny local business but quite large for the day. In 1803 an inventory showed that it had 63 vats containing 95,940 gallons of beer, with more elsewhere.” — Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. Battle and District Historical Society (BDHS) August 2017.

The family lived in a house next to the brewery. [6]Hardy, Sheila. The Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. 2011. Pp 19, 21.

In 1811, Robert Trotman died. John was given the opportunity to come in as a junior partner along with Simon Halliday and Mary Studd . [7]”A report in Ipswich Journal** dated 25 March 1811 announced that Studd, Halliday & Acton have purchased a brewery in St. Peter parish Ipswich (late belonging to Robert Trotman).” — Camra. Trotman, Robert brewery. Accessed August 2019 at https://suffolk.camra.org.uk/brewery/274&redirected [8]Langridge, Neil. Studd, Halliday and Acton brewery. Suffolk Real Ale Guide. Accessed August 2019 at https://suffolk.camra.org.uk/brewery/307

Several years of expansion followed for the business. In April 1813, they added a wine business, an inn in 1817, and then two inns in 1826 (by the end of 1827, they would own six inns in total.)

Entering the working world

On 30 March 1816, at the age of 18, she and a Miss Nicolson announced to the world in a newspaper ad that in a few days, they would be opening a boarding school for young girls:

“The following advertisement appeared in The Ipswich Journal: Miss Nicholson and Miss Acton respectfully inform their Friends and the Public that on 2nd April next, they intend opening a Boarding School for Young Ladies at the pleasant and healthy village of Claydon, near Ipswich… [Ed: north-west of Ipswich [9]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 2.

Eliza ran this Claydon school with Miss Nicholson for about two years before leaving.

It is not known why Eliza stopped working with her associate Miss Nicholson. But by the fall of 1819, she had opened another nearby at Great Bealings with at least one sister, possibly more. [10].”In 1819 she and a sister were running a new school at Great Bealings near Woodbridge, which appears to have lasted at least five years.” — Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. “The Misses Acton … have taken a house at Great Bealings near Woodbridge where they intend opening an Establishment for a limited number of Young Ladies on 29th September [1819]. [11]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 2.

The Claydon school under Miss Nicholson would end up closing a few years after she left: “…in July 1820 it closed. On the 28th and 29th of that month an auction was held at the house in Claydon of ‘the Household furniture and other effects of Miss Nicholson, declining her Seminary’.” [12]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton . The History Press. Kindle Edition.

The Great Bealings school under the Acton sisters seemed to do well for a period. By 1822, it had moved to a prime spot in nearby Woodbridge, [13]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 2. but it is not assumed the school lasted past 1825.

Around 1823 Eliza went to France, possibly as a governess to a younger lady, or as a lady’s companion. [14]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 3.

She was still in France in 1826: “we now have definite evidence that Eliza was in Paris in December 1826.” [15]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 3.

At the end of 1827, her father’s business had collapsed.

“In 1827, by which time John had been a partner for fifteen years, disaster struck. A local paper reported that John Acton, then residing at Calais, was bankrupt and the business was for sale… The auction notice in June 1828 showed the scale of the business: six pubs and half-ownership of another, a house and garden with a frontage of 180 feet, a wharf 224 feet long, and a mill house and brewery and related buildings. It was opposite St Peter’s church. As it happened, the buyers did no better, being declared bankrupt a few years later.” — Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton.

George Kiloh notes, “Calais was a favourite bolthole for debtors in the days when a prison term loomed before them.” [16]Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton.

By 1828, John’s wife, Elizabeth Acton, had leased on her own a large house named “Bordyke House” in Tonbridge, Kent, where she could take in boarders who were visiting the area for the waters at the nearby Tunbridge Wells. It is presumed that Eliza returned from France somewhat after this and lived with her mother. She may even have assisted her mother with the housekeeping and running the boarding house business. There is no record of John Acton ever living here.

Bordyke House (now Red House). The house includes the part on the side and goes quite far back. Neil Chadwick / 2011 / geograph.org / CC BY-SA 2.0

Eliza set herself to writing poetry. She self-published some small volumes of her poetry in 1826 and 1827 under her own name, printing 2,000 copies in all.

An 1841 census shows her living alone in the house with a female servant, and possibly shows her mother and father living in Grundisburgh, Suffolk, with Eliza’s brother Edward. [17]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton.Chapter 4.

An 1843 document concerning the house mentions that the rent was £50 a year, which was a lot, so it’s possible that Eliza kept up the business of taking in boarders that her mother had started. “…with such a high rent, it may have been essential for Eliza to have guests to share her costs.” [18]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 5. The practice of cooking for the boarders may have assisted her with knowledge to eventually write cookbooks. In her first cookbook, she would write that each recipe had been “proved beneath our own roof and under our own personal inspection.”

When a publisher, by the name of Thomas Longman, suggested to her that he needed a really good cookbook to publish (though this may just be an oft-repeated anecdote), she turned her hand to cookbook writing. This oft-repeated story is reputed to have taken place around 1835, and Longman is reputed to have said it in response to a volume of poetry she had proposed to him. By that time, poetry was falling out of fashion, but cookbooks were still few and far between, so it is plausible that a publisher would direct a writer’s attention to something he could make money on.

Modern Cookery

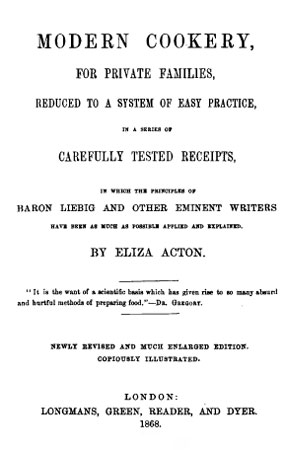

So, Eliza wrote a cookbook, which was first published in January 1845: Modern Cookery for Private Families. She was 46 years old. But the book had been underway for sometime.

“According to Eliza, her Modern Cookery was ten years in the making. The first advertisement for it appeared in The Morning Chronicle on 18 January 1845, so we know she must have started the work around 1834. It was from 1842 onwards that entries concerning ‘Acton’s Cookery’ first appear in Longmans Ledgers. In March 1844 there was an entry for a payment for thirty drawings of cooking utensils to illustrate the book, and that was followed in May by a payment to a Miss Williams for engravings and woodcuts…” [19]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 5.

Modern Cookery for Private Families, 1868 edition

Hers was the first cookbook in England to list ingredients separately and in precise quantities (though she put the ingredients after the instructions.) She had tested each recipe herself. She also introduced gentle humour and wit from time to time. And it turned out that she just plain had a gift for giving good, clear, intelligible directions in cooking.

People liked the format and the book was a huge success. Many decades of reprints would follow.

Her book was aimed at ordinary cooks, not for a chef with kitchen staff. Granted, as she was writing for middle-class women at the time, they might well have had a maid and a cook, but her audience was women with not enough staff that they could avoid involvement in the kitchen altogether.

The 1855 edition of Modern Cookery for Private Families added sections on “foreign food”, and Jewish ( Ashkenazi) cooking, and included many recipes for curry dishes. The book had what most believe is the first recorded recipe for Mulligatawny Soup. The book continued to be reprinted until 1914, when it fell completely out of fashion.

Acton later updated the section in the book on cooking meat to reflect the influential theories of chemist Justus von Liebig, who published his beliefs that searing the surface of meat sealed in the juices (he was wrong.) Her embrace of his ideas about meat influenced several succeeding generations of food writers who in turn embraced these mistaken beliefs.

The English Bread Book

As store-bought bread started to become more common in England, she tried to draw attention to the degradation of the product being sold to people:

“The adulteration of bread with alum and other deleterious substances, has lately excited the serious attention of the public and of the government, and caused searching investigation to be made as to the extent of this fraudulent practice. The result has not been satisfactory, but has thrown great discredit, without doubt, on one or two branches of English trade, which, above all others, ought to be secure from such abuse.” — Acton, Eliza. The English Bread Book. London: Longman. 1857. Page 20.

This inspired her to dedicate her second cookbook to bread. Entitled “The English Bread Book”, it was published in 1857.

“A country which possesses the agricultural and commercial advantages that England does, ought to be celebrated at least for the purity and excellence of its bread, instead of being noted as it is, both at home and abroad, for its want of genuineness, and the faulty mode of its preparation.” — Acton, Eliza. The English Bread Book. London: Longman. 1857. Page 1.

She baked her bread in crocks; she was uncertain of the newfangled “bread tins.”

Frontispiece from English bread-book for domestic use, adapted to families of every grade. 1857. Shrocat / wikimedia / 2018 / Public Domain

Eliza had social reform sympathies, as did many English writers of her time.

She had contact with Charles Dickens, also a social reformer, though they probably never met. In Modern Cookery for Private Families, she created a recipe she called “Ruth Pinch’s Beefsteak Puddings, à la Dickens” in honour of the character “Ruth” in Dickens’ “Martin Chuzzelwit.” Acton sent Dickens a copy of Modern Cookery for Private Families when it was first published, and received in return this note from him:

11 July 1845

Dear Madam,

I beg to thank you cordially for your very satisfying and welcome note of the tenth of January last; and for the book that accompanied it. Believe me, I am far too sensible of the value of a communication so spontaneous and unaffected, to regard it with the least approach to indifference or neglect -– I should have been proud to acknowledge it long since, but I have been abroad in Italy.

Dear Madam/ Faithfully Yours

Final years

“By 1841 the Acton family was together again, at Grundisburgh, a rather isolated village north-east of Ipswich; John died at Hastings in 1847. The 1851 census had Elizabeth (ex-Slatter) living at 3 Denmark Terrace in Hastings with her daughters Eliza and Catherine.” [20]Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton.

In the 1850s, she was living in a large house named Snowden House on John Street in Hampstead, London, which she was renting from a Robert Muter.

She would have been comfortable from the sales of her cookbooks.

“She had, of course, surrendered the rights of Modern Cookery to Longmans four years before her death. The £300 Longman paid for them hardly translates in today’s terms into a fortune, but to her it bought security, in the form of an annuity, allowing her to live a comfortable but hardly luxurious life.” [21]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 12. Biographer Sheila Hardy declines to convert that amount into today’s money, but George Kiloh ventures a guess: “Comparing historic and current values is never easy, but in terms of income that would represent about £320,000 today [2017].” [22]Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton.

Towards the end, she complained that many people were blatantly plagiarizing her books. Sheila Hardy writes:

“When Eliza complained bitterly in 1855 that others were plagiarising her work, she could not have known that within a year or so Mrs Beeton would have not only plundered her receipts – a third of Eliza’s soups and a quarter of her fish dishes, for example – but would also have taken Eliza’s innovation of listing the exact amount required of each ingredient. Clever plagiarist that she was, she put the list first rather than at the end and thus for generations she received the credit for this most important part of every recipe.” [23]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 12.

In the last half of her 50s, it is speculated that she was developing either cancer, or dementia.

“Eliza was probably never very well, and she began to ail towards the end of the 1850s. She died at Snowden House, John Street, Hampstead on 13 February 1859. She is buried in the local churchyard there. A blue plaque has been placed in her memory at the house in Tonbridge. She never married” [24]Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton.

Though she never married, some sources feel she may have had a child, by way of a French officer with whom it’s believed she had a romance while in France. Some believe she was even engaged, though for undisclosed reasons the marriage never took place, and Acton returned to England.

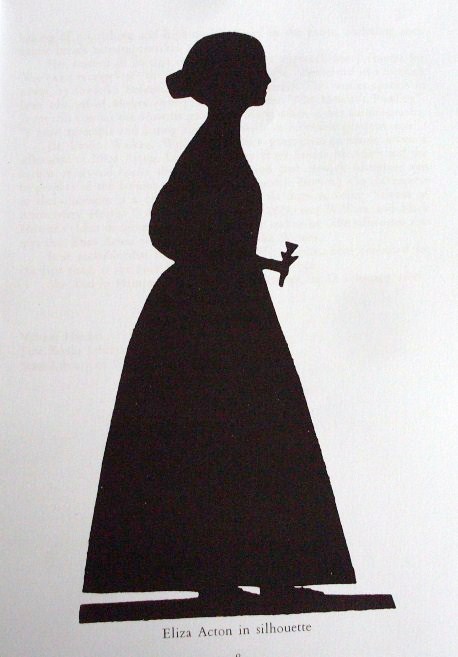

Images of Eliza Acton

No images of her have survived. There is, however, a silhouette.

Eliza Acton / Public Domain

A biography Sheila Hardy writes:

“Eliza Acton died as she had apparently lived, out of the glare of the limelight. She has been described as a shadowy figure so it is not surprising that the only known image of her is a silhouette very similar in style to the more familiar one of Jane Austen. The word ‘neat’ springs to mind to describe the figure in the reproduction in First Catch Your Kangaroo [Ed: an Australian book about food by William Howitt 1792 – 1879]. She appears to be of medium height and slim build; her hair is tied back into the tidy little bun in fashion at the time. Gaze long enough on the profile and one can imagine a little smile playing around her lips. Eliza’s silhouette was one of a trio of ladies, all of whom are described on the back as being friends of Anna Howitt, the eldest daughter of Mary and William. Maybe it is a good thing we have no formal portrait of her, it might prove disappointing. Instead, we can make her live in our imagination. In the same way she left no pictures of herself, neither did she leave any other useful documentation.” [25]Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton . The History Press. Kindle Edition.

One image circulating on the internet purportedly of her is believed instead to be of a “Julia Eliza Northey Hopkins/Shum” [26]Discussion at wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eliza_Acton_1799-1859.png ; another is actually of Mrs Beeton. An engraving also circulating is of a Mrs Francis Elizabeth Acton.

Cookbooks

- Modern Cookery for Private Families (1845. Link valid as of August 2019)

- The English Bread Book (1857. Link valid as of August 2019)

Literature & Lore

“It may be safely averred that good cookery is the best and truest economy, turning to full account every wholesome article of food, and converting into palatable meals what the ignorant either render uneatable or throw away in disdain.” — Eliza Acton. Modern Cookery for Private Families. 1845.

“As culinary historian Nicola Humble says, ‘Acton was the Elizabeth David of her day’, while the reliable and reassuring Beeton was more of a Delia Smith.” — The First Star Cooks. London, England: The Daily Mail. 18 May 2019.

From Modern Cookery for Private Families by Eliza Acton (London: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer, 1871. p.48.). 1871. Scribblingwoman / wikimedia / 2007 / Public Domain

References

| ↑1 | ”When the famous Mrs Isabella Beeton decided to publish her iconic Book Of Household Management she became a shameless plagiarist, and the writer she pillaged most blatantly was her predecessor Eliza Acton, a Victorian spinster whose Modern Cookery For Private Families, published in 1845, was the first to set out ingredients, quantities and timings in the methodical format we expect today. Except she gave method first, then ingredients – Mrs Beeton’s innovation was to turn this round.” The First Star Cooks. London, England: The Daily Mail. 18 May 2019. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Preface. Hardy, Sheila. The Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Stroud, England: The History Press. 2011. |

| ↑3 | Ray, Elizabeth. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. 2004. |

| ↑4 | ”Eliza was born at Battle on 17 April 1799, being baptised at St Mary’s on the next 5 June. Her father was John, born at Hastings in 1775, and her mother Elizabeth Mercer of East Farleigh in Kent; John’s father was Joseph, a major presence at Hastings and elsewhere nearby, who had married Elizabeth Slatter of Battle. The Slatters were well-known as tradesmen and minor property owners in the town. Joseph’s brother in law George was a grocer who also sold china and wines and spirits; George’s brother was a butcher.” — Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. Battleford District Historical Society (BDHS) August 2017. Accessed August 2019. |

| ↑5 | Glyde, John. The New Suffolk Garland. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co. 1866. Page 376. |

| ↑6 | Hardy, Sheila. The Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press. 2011. Pp 19, 21. |

| ↑7 | ”A report in Ipswich Journal** dated 25 March 1811 announced that Studd, Halliday & Acton have purchased a brewery in St. Peter parish Ipswich (late belonging to Robert Trotman).” — Camra. Trotman, Robert brewery. Accessed August 2019 at https://suffolk.camra.org.uk/brewery/274&redirected |

| ↑8 | Langridge, Neil. Studd, Halliday and Acton brewery. Suffolk Real Ale Guide. Accessed August 2019 at https://suffolk.camra.org.uk/brewery/307 |

| ↑9 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 2. |

| ↑10 | .”In 1819 she and a sister were running a new school at Great Bealings near Woodbridge, which appears to have lasted at least five years.” — Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. |

| ↑11 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 2. |

| ↑12 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton . The History Press. Kindle Edition. |

| ↑13 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 2. |

| ↑14 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 3. |

| ↑15 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 3. |

| ↑16 | Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. |

| ↑17 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton.Chapter 4. |

| ↑18 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 5. |

| ↑19 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 5. |

| ↑20 | Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. |

| ↑21 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 12. |

| ↑22 | Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. |

| ↑23 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton. Chapter 12. |

| ↑24 | Kiloh, George. Eliza Acton. |

| ↑25 | Hardy, Sheila. Real Mrs Beeton: The Story of Eliza Acton . The History Press. Kindle Edition. |

| ↑26 | Discussion at wikimedia https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Eliza_Acton_1799-1859.png |