Elizabeth Raffald (1733-1781). From the 1782 edition of The Experienced English Housekeeper published by Baldwin. Begoon / wikimedia / 2019 / Public Domain

Elizabeth Raffald was the author of the 1769 book, “The Experienced English Housekeeper.” She provides 800 recipes written with such clear directions and quantities, that you can still cook from them today.

Elizabeth definitely saw herself as a “modern” woman. She lived in Manchester, a burgeoning industrial centre of the British Empire.

Early years

Elizabeth Raffald was born Elizabeth Whittaker in Doncaster in 1733. Her father was John Whittaker of Doncaster, a school teacher who drummed some education into her.

In 1748, at the age of 15, Elizabeth began working as a housekeeper for several different families in Yorkshire before settling as a housekeeper for Sir Peter and Lady Elizabeth Warburton of Arley Hall, in Arley, Great Budworth, near Northwich, Cheshire. She worked for Lady Elizabeth for the next fifteen years.

Arley Hall. Arley, Cheshire, England. Jeff Buck / geograph.org / 2015 / CC BY-SA 2.0

On 3 March 1763, in Great Budworth, she married John Raffald, originally from Stockport, near Manchester, who also worked for Lady Elizabeth Warburton, as head gardener. They moved to Manchester. The couple would have a number of daughters (some sources say fifteen; some say sixteen; some say nine, with only three surviving.) [1]”In eighteen years she had sixteen daughters.” (The Annals of Manchester. Edited by William E. A. Axon. 1886.) Alan Davidson (The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002, p. 777) says: “Many accounts, copying the same erroneous source, state that she had sixteen children, all daughters; the church registers reveal six.” He agrees that three daughters survived her.

Raffald goes into the food business

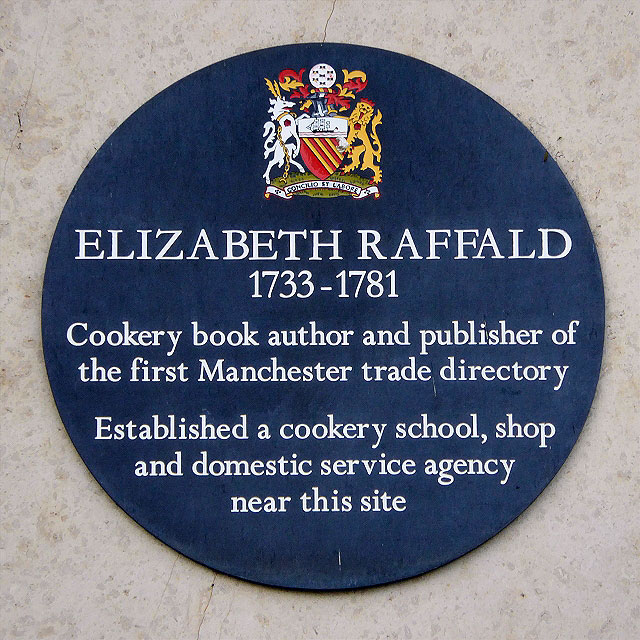

In 1764, Elizabeth opened a confectionary store on Fennel Street in Manchester. Out of the store, she also ran a cooking school for young women. The store is described as a “confectionary”, but it was more like what we would call now a deli, selling not only sweets, but also cooked meats, and soup (which is why some food writers also refer to her as a “caterer.”) She also sold ready-made centrepieces for tables. At some point at this address, she also ran an employment agency for servants. Meanwhile, her husband helped run a vegetable stall at the market with other members of his nearby Stockport family.

In 1766, Elizabeth moved her store to the Market Place.

Elizabeth Raffald Commemorative Plaque, Exchange Square, Manchester.

In 1768, she ran an ad for her store in the Manchester Mercury listing, amongst other things for sale, “Plumb cakes for weddings.”

The Experienced English Housekeeper

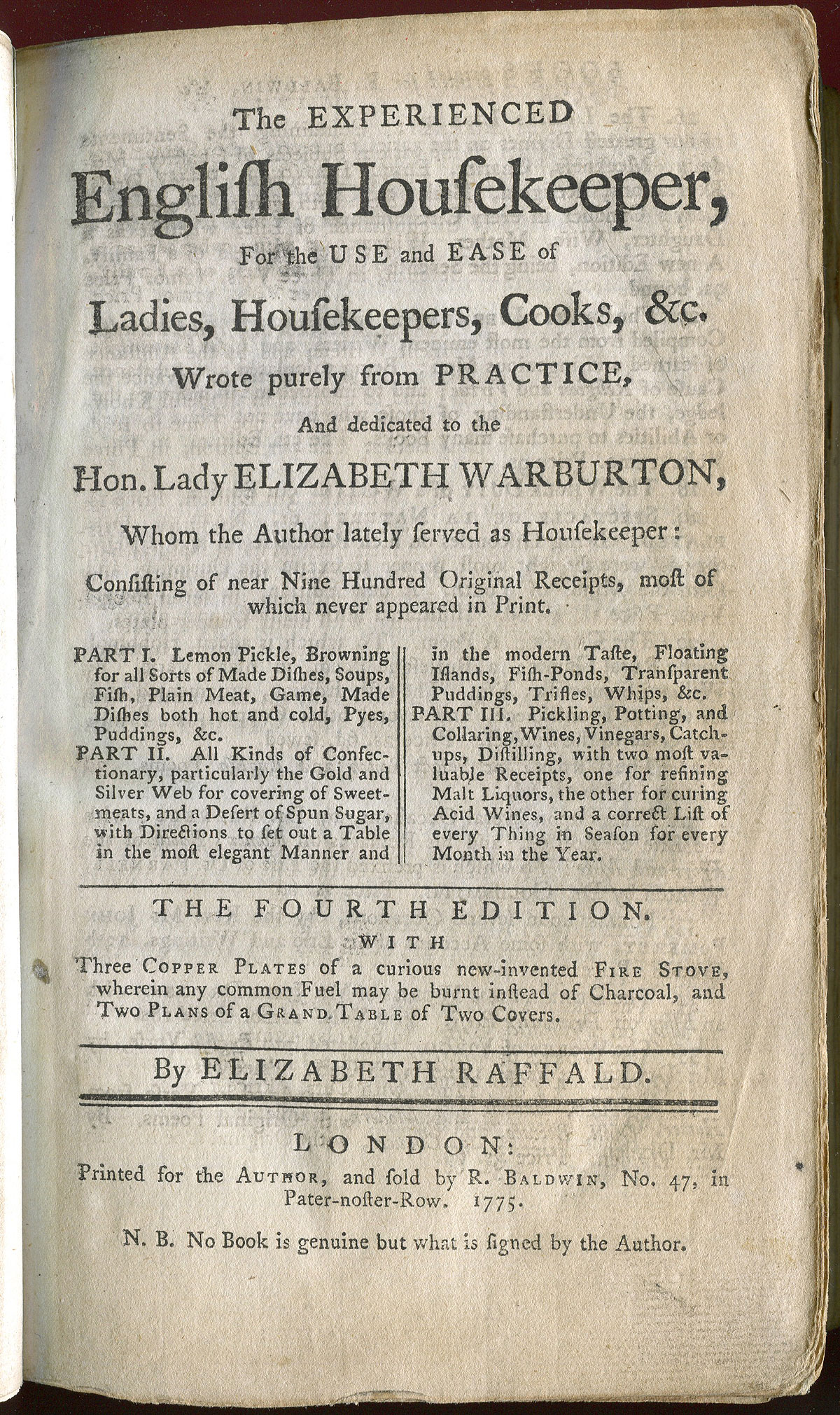

In 1769, Elizabeth published her book, “The Experienced English Housekeeper”, and dedicated it to Lady Elizabeth Warburton. She had 800 copies printed, and sold them all at five shillings each. All the recipes were original; not copied from other sources.

Title page of Elizabeth Raffald’s ‘The Experienced English Housekeeper’. Chiswick Chap / wikimedia / 2014 / Public Domain

Showing that the use of “modern” is a relative term in every age, she writes: “[I] have made it my Study to set out the Dinner in as elegant a Manner as lies in my Power, and in the Modern Taste.” She aimed the book at people working for wealthy families, and in Manchester, there were more newly-wealthy families every year. The book also was evidently a favourite of Queen Victoria, who copied small portions of it into her diaries.

Elizabeth gives recipes on how to make jellied dishes, and salad dressings from oil and an acid such as vinegar or lemon. She advises how to set a table for a formal occasion (complete with illustrations), and how to cure bacon, advocating lots of salt so that it will “shine like diamonds on your bacon.” And she wasn’t stingy with ingredients: when making omelettes, she calls for 4 oz (125 g) of butter per 6 eggs.

The book was first printed by in Manchester by “J. Harrop, for the author, and sold by Messrs. Fletcher and Anderson, London.” The print run was eight hundred. [2]”I have a signed copy of the second edition printed in 1771, by R. Baldwin, No 47 in Patter-Noster Row. Not many of the second edition survived as there were only 400 copies printed. The first edition (1769) had a print number of 800. Elizabeth Raffald signed all her cookbooks, at least the first and second editions. I have not seen many of the following editions, but I know at least until the fifth edition this is the case. She did this so you would be able to spot a copy, since there were many of those made from her cookbook.” — Correspondence on 2 February 2009 with Laurens Vellekoop, USA, who owned a signed copy of the 1771 printing.

The second printing, of four hundred more copies, in 1771, was done by R. Baldwin of 47 Paternoster Row, London [3]. To meet demand, the book was printed again in 1775 and 1778. The 1775 printing added 100 additional recipes. In 1801, the book was adapted for the American market.

By 1784, there were thirteen legal print editions in all, and twenty-one pirated versions.

The book is divided into three parts:

- “Part First”: Lemon Pickle, Browning for all Sorts of Made Dishes, Soups, Fish, plain Meat, Game, Made Dishes both hot and cold, Pyes, Puddings, &c,

- “Part Second”: All Kind of Confectionary, particularly the Gold and Silver Web for covering of Sweetmeats, and a Desert of Spun Sugar, with Directions to set out a Table in the most elegant Manner and in the modern Taste, Floating Islands, Fish Ponds, Transparent Puddings, Trifles, Whips, &c.

- “Part Third”: Pickling, Potting, and Collaring, Wines, Vinegars, Catchups, Distilling, with two most valuable Receipts, one for refining Malt Liquors, the other for curing Acid Wines, and a correct List of every Thing in Season in every Month of the year.

Innkeeping

After publication of the book, she temporarily ran the Bull’s Head Inn in the market place, Manchester for a few months in 1769.

In 1770, Elizabeth switched to running the King’s Head Inn in Chapel Street, Salford, across the river. The stage to London ran from there. She established a post office in the King’s Head, and rented out carriages. Ultimately, though, this business would not do well.

Other publishing efforts

In 1771, Elizabeth helped establish Salford’s first newspaper, called “Prescott’s Journal.” She also became part owner of Harrop’s Mercury.

In 1772, Elizabeth wrote and published a street directory for Manchester and Salford (republished 1773, 1781.) Sometime after 1772, she and her husband gave up the Salford business, and in debt from it, Elizabeth then catered for the Kersal Moor race course, and by 1781, for the Coffee Exchange House in Manchester, of which her husband had become “Master.”

In 1773, Elizabeth sold the rights to “The Experienced English Housekeeper” for £1,400 to its publisher, R. Baldwin, 47 Paternoster Row, London.

Reprinting of the book began with a second edition in 1775. CooksInfo.com knows of a fourth edition that was done in the same year [3]Correspondence on 7 February 2008 with Stuart McLucas, UK, who owned a fourth edition dated 1775, signed by the author.

Final years

On Thursday, 19 April 1781, Elizabeth came down with spasms, and died within the hour. She was buried at Stockport Parish Church.

One week later, her creditors came after her husband. He didn’t, apparently, have a very good sense for business, and he was a spendthrift to boot; Elizabeth had been the business brains in the family.

Two “line engravings” by a P. McMorland are listed as “published” in 1782. Given that she is also listed as the sitter, they must have actually been done prior to her death. The engravings are now owned by the National Portrait Gallery in London.

Books by Elizabeth Raffald

- 1769. The Experienced English Housekeeper. Manchester: Printed by J. Harrop.

- 1772. The Manchester Directory. Printed for & Sold by the Author & J. Harrop, opposite the Exchange

- 17xx. Elizabeth wrote another book on midwifery, with advice from Charles White (1728 — 1813), but didn’t have time to finish it and left it in manuscript form. It may be that after her death, her husband sold it to a publisher, but it is not known whether it was actually published.

Literature & Lore

Elizabeth gave a recipe in “The Experienced English Housekeeper” for “Bride Cake”. It’s often cited as one of the first recipes in print in English for Wedding Cake.

“To make a Bride Cake. Take four Pounds of fine Flour well dried, four Pounds of fresh Butter, two Pounds of loaf Sugar, pound and sift fine a quarter of an Ounce of Mace, the same of Nutmegs, to every Pound of Flour put eight Eggs, wash four Pounds of Currants, pick them well and dry them before the Fire, blanch a Pound of sweet Almonds (and cut them length-ways very thin), a Pound of Citron , one Pound of candied Orange, the same of candied Lemon, half a Pint of Brandy; first work the Butter with your Hand to a Cream, then beat in your Sugar a quarter of an Hour, beat the Whites of your Eggs to a very Strong Froth, mix them with your Sugar and Butter, beat your Yolks half an Hour at least, and mix them with your Cake, then put in your Flour, Mace and Nutmeg, keep beating it well ’till your Oven is ready, put in your Brandy, and beat your Currants and Almonds lightly in, tie three Sheets of Paper round the Bottom of your Hoop to keep it from running out, rub it well with Butter, put in your Cake, and lay your Sweet-meats in three Lays, with Cake betwixt every Lay, after it is risen and coloured, cover it with paper before your Oven is stopped up; it will take three hours baking.”

Videos

‘Eggs and Bacon in Flummery’ from Elizabeth Raffald’s 1769 Experienced English Housekeeper.

References

| ↑1 | ”In eighteen years she had sixteen daughters.” (The Annals of Manchester. Edited by William E. A. Axon. 1886.) Alan Davidson (The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002, p. 777) says: “Many accounts, copying the same erroneous source, state that she had sixteen children, all daughters; the church registers reveal six.” He agrees that three daughters survived her. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”I have a signed copy of the second edition printed in 1771, by R. Baldwin, No 47 in Patter-Noster Row. Not many of the second edition survived as there were only 400 copies printed. The first edition (1769) had a print number of 800. Elizabeth Raffald signed all her cookbooks, at least the first and second editions. I have not seen many of the following editions, but I know at least until the fifth edition this is the case. She did this so you would be able to spot a copy, since there were many of those made from her cookbook.” — Correspondence on 2 February 2009 with Laurens Vellekoop, USA, who owned a signed copy of the 1771 printing. |

| ↑3 | Correspondence on 7 February 2008 with Stuart McLucas, UK, who owned a fourth edition dated 1775, signed by the author. |