A Garnish is an element added to food when it is served.

In modern times, the main purpose of a Garnish is visual, but a Garnish may sometimes also serve to complement or contrast with the taste of the main dish. The Garnish can be placed on top of food or around it.

Parsley may be the most often used — and discarded — garnish in our times. It’s little known that it does, in fact, have a purpose (in theory at least), that of sweetening the breath after eating.

Simple garnishes used in everyday cooking are chopped chives, parsley or other herbs, grated cheese, a drizzle of olive oil, or a wedge or thin slice of lemon, especially with fish. Sometimes what is deemed a garnish is a bit arbitrary: a sprinkle of paprika would be considered a garnish, while the same of ground black pepper is considered seasoning.

Cocktail drinks may be garnished with pieces of fruit.

Not all garnishes are edible. Sushi is often garnished with the plastic grass called “baran”, and cocktails may come with cocktail umbrellas in them.

Garnishes were once seen as fancy, but by the end of the 1900s, had started to take on a “tacky” air. The same garnishes had been done to death for decades by mid-range restaurants and caterers: tomato roses, carrot flowers, gelatin cutouts, shaped butter pats, piped cream cheese. Most of these are just pushed aside on the plate or on the buffet serving platters.

Still, some dishes aren’t really themselves without their garnish: people definitely expect cherries on banana split sundaes.

On buffet platters, Garnishes are usually arranged around the main item, and are usually items that are easy for people to handle when serving themselves: for instance, broccoli or asparagus spears, versus peas.

Professional and keen home garnishers acquire a battery of specialized tools from butter curlers to melon ballers to piping bags.

Garnishes in Classical French Cooking

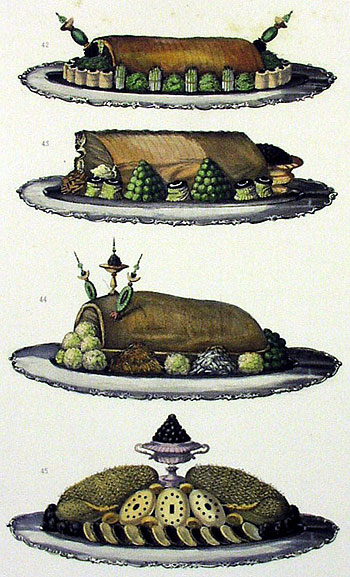

In classical French cooking, garnishes were more than just visual or complementary flavour items: they were far more substantial. They were accompaniments to the main food item; what one used to call “the trimmings”, or side dishes. They were definitely part of the meal, and not something you’d push out of the way to get at the food. In fact, Larousse Gastronomique (1977 edition), recommended allowing 100g (3 ½ oz) of Garnishes for each diner.

Many of these Garnishes were complex and elaborate side dishes in their own right. But then, these were not meant for home kitchens. These types of Garnishes were meant for professional kitchens, with underlings to prepare them.

These classical French garnishes have defined names, usually being named after a person, place, thing, event or occasion. By 1914, the book “Répertoire de la Cuisine” by Louis Saulnier listed 209 defined, named Garnishes. Each Garnish also had defined ingredients, preparation and assembly methods. They weren’t just whizzed up on the fly from spare bits floating about in the restaurant kitchen.

The names of these Garnishes have had some influence in modern kitchens, though their application has been vastly simplified. Many people would know that a dish with Florentine in the name means that spinach is involved somehow, though fewer would know that Clamart indicates peas, and Parmentier indicates potatoes. Printanière was classically a definite collection of spring vegetables prepared in a definite way. Now, the term is used more generally to indicate a side accompaniment of fresh vegetables, particularly those first to appear in a growing season, with the choice of vegetable and preparation method left up to the cook. In fact, the terms bouquetière, jardinière, and printanière, indicating very different vegetable sides, are used relatively interchangeably these days to indicate a vegetable accompaniment of pretty much any sort.

The classical French kitchen distinguishes between two broad categories of Garnishes, simple and composite.

Simple Garnishes are something such as a single vegetable, a grain such as rice, or something made from flour (a small savoury tart, or a crouton, as in a large piece of fried bread.) For vegetables, the typical cooking methods include stewing or braising; typical added ingredients are butter, cream, breadcrumbs.

Compose Garnishes have a number of ingredients in them. All those ingredients need to complement each other, and then as a whole compliment the main dish. Some elaborate Garnishes might be held together or affixed to a joint of meat using a now pretty much defunct kitchen tool called an “Attlet”: a small, decorative metal skewer.

Though some of the classical French garnishes were complex, the rules around how to serve them were pretty common sense. If a joint of meat were being served on a platter for carving at the table, and the Garnishes were solid, they could be arranged around the joint. If the Garnishes were runny, like a purée of something, then they would be served in separate dishes so as not to run all over the platter.

Pastas and grains were served separately, rather than on a platter, so that they wouldn’t become marred by absorbing the meat juices. As for sauces for garnishing meat or fish, just a little of it would be drizzled on the meat or fish on the platter, and the rest served in a sauce boat, so as not to drown the food item from view.

If a cut piece of meat were being served Russian style (already plated), and risked being hidden by Garnishes, you’d raise the piece of meat up on a crouton, or a bed of something so that it could be seen.

Poached fish in the French tradition is usually served garnished with boiled or steamed potatoes, and parsley. Grilled fish has slices of lemon as well

Cooking Tips

Apply Garnishes to food just before serving. That being said, many Garnishes can be prepared ahead: some will require refrigeration (wrapped, so that they don’t dry out.) Others, meant to be dry and crispy, are let stand at room temperature. Some carved vegetables are best held in ice water to keep them crisp and holding their shapes.

The colour of some vegetables for Garnishes is enhanced if they are blanched first for one minute, then plunged into an ice bath.

Language Notes

“Garnir” in French is “to garnish.” “Garni” means “garnished.” A “garniture” is a garnish.

Sources

Gisslen, Wayne. Essentials of Professional Cooking. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. 2004. Volume 1, pp 487 – 489.