Modern attempt at garum. © CooksInfo / 2020

Garum was a fermented fish sauce in classical times. It was made first by the Greeks and then by the Romans.

The Greeks had made a fish sauce they called “garos”, which was also a Greek word for a type of fish. When Greek slaves became cooks for Romans, they made it for the Romans. The Romans loved the sauce, took it over and made it their own, the way pizza became an American dish, and they used it far more than the Greeks had.

Garum was a very basic product that everyone used, as we use ketchup or Worcestershire sauce today. It would add saltiness to a meal, and complement and bring out other flavours in a dish. Romans loved all food to have combined tastes of sour, sweet and salty, and the garum helped in this balance. The Romans even mixed wine in with it to drink it.

The Greeks today still make something they call “garos”, which is a relish made from mackerel livers.

Pliny the Elder has let us know that he hated garum.

Garum production

A recipe for it written down by Gargilius Martialis in De Medicina et de Virtute Herbarum is still extant, though the proportions aren’t given; it used fresh whole mackerel, sea salt, herbs. The mackerel were layered with the salt and herbs between them, and then let ferment in the sun for 20 days. Over the following 40 days, it was stirred every day. Then it was filtered through muslim to make a salty, oily sauce that was apparently odourless.

The salt drew water and juices out of the fish and started to make a sauce. The fish fermented, and broke down into a liquid. It was an enzyme in the fish intestines that caused the breakdown; it was not decay or putrefaction. There was too much salt for any bacteria to develop.

Some garum may have been made just using the blood and intestines from mackerel. It’s possible the sauce started as something that would use up the bits of fish — the entrails, etc — that were left after the fish were cleaned for eating. This might have been particularly true with the poorer Greeks. But in the hands of the wealthier Romans, it became more than just a way of using up fish leftovers. Other fish sauces could be made from other fish (muria was made from tuna) but for garum, mackerel was generally considered to make the best sauce, though at one point, mullet was in fashion.

The recipes of course varied in how much salt was used, when and which herbs were added, how long it was fermented, etc.

Garum smelled while you made it, but once made it had little smell and what aroma it did have people loved. Good garum didn’t have a fishy taste; it had a complex, layered, salty taste.

Still, people were prohibited from making it at home, though, because neighbours would complain about the smell while making it. If bottled garum smelled bad, then it had gone bad.

Production areas

Several regional variations of garum evolved.

Garum made in Portugal — then called Lusitania — was considered amongst the best. In Southern Spain and in Portugal, it was big business, and there were large purpose-constructed factories. The factories had tanks in the ground with a roof overhead. The bases of many of these pillars that supported the roofs are still extant. In Portugal, there are still the remains of a large factory at Troia, at the mouth of the Sado river, as well as the ruins of the baths which the Romans built for the workers. The garum factories would be located on shores along the coastlines, close to the source of fish — and away from neighbours who would complain about the smell.

Garum sociorum was considered at one point the best type of fish sauce (it means “garum for friends”.) It was apparently made in Spain from the livers of mullet fish.

Garum factory at Baelo Claudia, Baetica, Spain. Carole Raddato / flickr / 2016 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Garum and tapeworms

Dr Piers Mitchell (Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, University of Cambridge) notes that fish tapeworm became widely present in the Roman Empire era, even though it had not been before that in Bronze and Iron Age Europe. He postulates that garum was responsible for a rise in fish tapeworm transmission throughout the Roman empire.

“One possibility that could explain a change in fish tapeworm distribution in the Roman period is the Roman enthusiasm for fish sauce, known as garum, liquamen or muria (Cool, 2006, 58). It was not only used as a culinary ingredient, but also as a medicine (Curtis, 1984). Garum was a fermented sauce made from pieces of fish, herbs, salt and flavourings. This sauce was not cooked, but allowed to ferment in the sun (Curtis, 1983). Garum seems to have its origins in the Mediterranean region, but over time was made in northern Europe where fish tapeworm was much more common. Archaeological examples of garum in Roman pottery vessels have been recovered at many sites, and the bones of fish from these pots include both sea fish and fresh water fish (Van Neer et al. 2005; Locker, 2007). Garum was traded right across the empire, ensuring that people living in regions that were not endemic for fish tapeworm would still have been at risk of contracting the parasite (Curtis, 1988; Haley, 1990). It is quite possible that this fermented fish sauce may have acted as a vector for the spread of fish tapeworm and hence contributed to the rise in the archaeological evidence for fish tapeworm in the Roman Empire….After considering possible explanations, it seems plausible that the Roman enthusiasm for the fermented fish sauce known as garum may have acted as a method where fish tapeworm eggs could have been transported large distances across the empire and then be consumed without being subjected to cooking.” [1]Mitchell PD. Human parasites in the Roman World: health consequences of conquering an empire. Parasitology. 2017;144(1):48‐58. doi:10.1017/S0031182015001651

Substitutes

Some have tried using Vietnamese fish sauce, Nuoc Mam, or the Thai Sauce Nam Pla, but others feel that these two modern sauces taste more like a soy sauce than a fish sauce, and that it isn’t pungent enough, as it uses cleaned fish, and doesn’t use the innards.

Garum was definitely a sauce, as opposed to a paste: it was pourable.

History Notes

Garum was one of Pompeii’s main exports.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire kept on making the sauce.

Literature & Lore

Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, in The Physiology of Taste, Dec 1825, writes: “Garum was dearer (than muria), and we know much less of it. It is thought that it was extracted by pressure from the entrailles of the scombra or mackerel; but this supposition does not account for its high price. There is reason to believe it was a foreign sauce, and was nothing else but the Indian soy, which we know to be only fish fermented with mushrooms.” (Note that Brillat-Savarin also reveals that the French of his time didn’t really know what soy sauce was.)

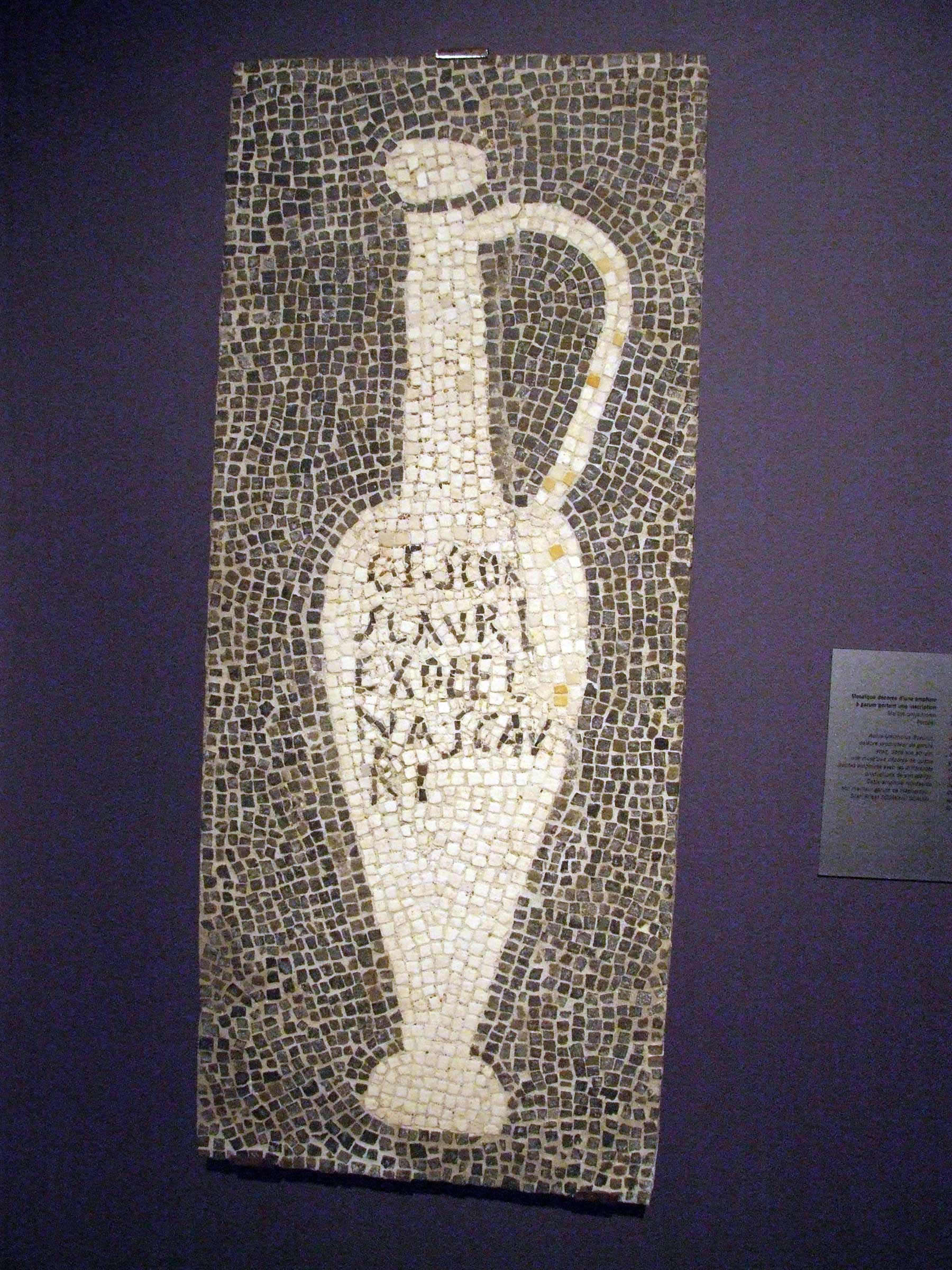

Garum jug mosaic found at Pompeii. The inscription reads: G(ari) F(los) SCOM(bri) SCAURI EX OFFI(ci)NA SCAURI. Claus Ableiter / wikimedia / 2007 / CC BY-SA 3.0

References

| ↑1 | Mitchell PD. Human parasites in the Roman World: health consequences of conquering an empire. Parasitology. 2017;144(1):48‐58. doi:10.1017/S0031182015001651 |

|---|