Measuring cups. © Denzil Green / 2018

A measuring cup is a demarcated vessel used to measure ingredients.

The US and Canada customarily use measuring cups to measure both liquid and dry ingredients, while the rest of the world primarily uses measuring cups solely for liquid ingredients.

In North America, there are separate cups for dry measure and cups for liquid measure. The single difference between wet and dry cups are the rims. Liquid ones have a pour spout on them, dry ones don’t.

These measuring cups are designed solely for measuring; they are never used at the table or otherwise for drinking liquids out of.

The challenges of using cups as a measurement

One of the difficulties in measuring with cups is that “a cup” is not a legally defined term nor is it a term of commerce. Items that are measured in American kitchens by volume using cups, such as sugar, butter and flour, are actually sold by weight. A pound of flour is always a pound of flour, whether sifted or not, but this is not so for a cup of flour. If you take a cup of flour and sift it and put it back in the cup, you will now have more than a cup of flour because the added air in the flour will have increased the volume of it. Another example is a cup of walnuts: whole, halved, chopped, and ground will all yield a different weight of walnuts.

In an attempt to control this possible disparity, recipe writers will often attempt to describe precisely how they want you to put the ingredient in the cup by using adjectives such as generous, loosely-packed, tightly-packed, scant, rounded, heaping, sifted, level, etc.

Coffee machine makers seem now to refer to a cup as something that must be a 100 or 125 ml (3 or 4 oz) cup. Their cup measurement doesn’t match up with any kitchen measuring cup, let alone any coffee cups or mugs that anybody actually uses to drink out of. But they can do that, as cup is not a legally defined term.

Dry measuring cups

Dry measuring cups are meant to be filled right up to their rim. They generally look like large measuring spoon sets. They have straight sides, flat narrow rims and flat bottoms. The idea is that you take a knife and whoosh it across the top to level it off. Good ones have the measurement both on the handle, and on the back, so that if you hang them up, you can easily see the measurement on the back for quick access.

Dry measuring cups are easy to use as scoops straight in the flour bin, etc. Some put very long handles on them for just this purpose, so that your knuckles don’t end up dusted in flour. But if the handles are too heavy, they won’t sit level on a counter — the heavy handles just tip the flat bottoms over. Be careful, though, using metal ones to scoop up stuff like hard butter, etc: the handles tend to bend easily.

Dry measuring cups are actually technically liquid measures — they measure in volume. 1 cup of water from them will be 8 oz, just as in a liquid cup. There is no official “dry cup” — there couldn’t be, as dry varies so much depending on what you are weighing: rice, macaroni and flour don’t fit into the cup in the same way, so it’s only the volume that is measured, not the actual quantity in weight.

In practice, most people just use what they have as a dry measuring cup, which tends to be a liquid one. You put in the flour, shake it then eyeball it — as generations of Americans and Canadians have now done.

Dry measuring cups come in sets of 1/4/, 1/3/, ½ and 1 cup; odd-size dry measuring cups are ⅔ cup, ¾ cup and 1 ½ cups. They are made in plastic and metal.

Most cooking instructors direct you to buy both. In truth, measuring cups are hardly ever labelled as such in the stores, perhaps because few outside of Home Economics instructor circles really know the difference. If you did manage to find some with packaging clearly labelled as one or the other, unless you knew the difference to look for you, some people may not be able to remember which was which after they got the packaging off.

Dry weight measuring cups

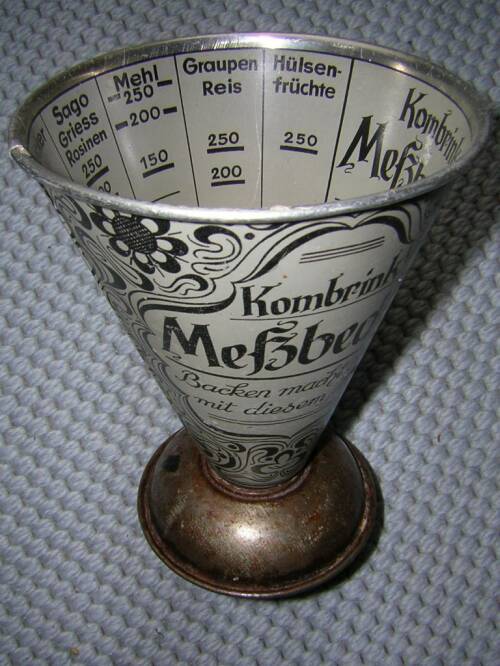

In countries where dry ingredients are typically measured precisely using kitchen scales, cheat measuring cups do exist.

They are typically conical-shaped, with demarcations inside that approximate what the weight of something would be when measured as a volume. They will allow “quick and dirty” weight measurement of common dry goods such as barley, coconut, flour, lentils oats, raisins, split peas, sugar, tapioca, uncooked rice, etc. Popular models are made by Tala and Dr Oetker.

Conical measuring cup for dry ingredients. Kasselklaus / wikimedia / 2004 / Public Domain

Liquid measuring cups

Liquid measuring cups have a pour spout on them, which dry ones don’t. Many will have enclosed handles so that the cup can be hung from hooks. Pyrex ones always used to have such a handle, but around 2000 they started putting out more cramped handles that are open at one end, and so they can’t hang on a cup hook. The idea reputedly is that they can be stacked instead.

They are generally made of glass or plastic, with glass being more usual. Either will have the measurements marked off at the sides. Most glass ones are made of a heat-resistant glass such as Pyrex. Transparent plastic ones can cloud over with time, making it harder to see clearly how close the liquid you are measuring is matching up to the marks.

To accurately measure liquids, you have to raise a measuring cup to eye level or crouch down to its level on the counter. The top measurement line is always a bit down from the rim, so that when you need to measure the full amount, it won’t spill over the edges.

Very large liquid measuring cups (such as the 2 US quart / litre) can double as mixing bowls, and are sometimes referred to as “batter bowls.” These often come with plastic lids so they can also be used for microwave cooking as well.

Alternative Models

Adjustable measuring cup. © Denzil Green / 2018

Some measuring cups are designed as “sliding bars.” You move the handle, which in turn moves a dividing compartment in the cup portion, to decrease or increase the volume of the area available to hold ingredients.

Another novel design is that of a plastic cylinder fitting snugly around a sliding tube. Called a “Measure-All® Cup”, a “Push Up Cup” or a “Wonder Cup” (yes, it is starting to sound like something else, isn’t it?), you push the tube up or down inside the cylinder to the right measurement line you want, then fill. As you add ingredients, you raise the tube to line the measuring lines up with what you have already put in, and then measure the next ingredient in. In this way, it works a bit along the same principle of taring an adjustable electronic weigh scale. This design is used for solids, or semi-liquids like honey or mustard, but not liquids. They are particularly handy for ingredients like jam, peanut butter or butter that can otherwise be hard to get out of measuring cups: you just push the tube up, forcing the ingredient out of the top.

Accessibility

A few measuring cups, such as those designed by OXO, are now designed in such a way that looking on them from overhead will give an accurate measure. This means you don’t have to crouch down to counter height.

These cups are actually divided in two by a slanting piece of plastic, with the half behind the plastic shut off, out of use, and on the slanted divider inside are the measurements, though measurements also on the outside. Some people feel, though, that the angles created inside the cup make it hard to scrape ingredients out.

Most measuring cups are designed for right-handed people.

Some measuring cups for those who are blind or have impaired vision have raised measuring lines on the insides of the cups, so you can feel where what you are measuring is at.

Displacement method

This is a method for measuring solid, “water proof” ingredients such as shortening, lard or butter that is taught in home economics classes. It is considered more accurate than trying to pack it in, then scrape it out, but it is more work.

Using this method, if the measurement needed were ½ cup shortening and you have a 1 cup capacity measuring cup, you would fill the cup ½ full of cold water and add shortening. When the water reaches the 1 cup mark, you have added ½ cup of shortening. You pour off the water and the ½ cup shortening remains.

Alternatively, shortening may be placed on the kitchen table until it softens enough to pack it accurately in the cup, or, you can pack harder shortening or butter into the cup tablespoon by tablespoon to avoid leaving large air gaps.

UK cups

America calls its measuring system “English”, but the truth is, contemporary Brits tend to measure dry or solid ingredients by weight, not volume.

Brits do, though, use measuring cups for liquids. But they tend to call them “measuring jugs”, and they tend to be delineated in pints, not cups. Brits relate to “pints” (British pints of course, being 20 oz. as opposed to 16 oz. in the USA), and where North Americans might say “1 cup” (8 oz.), Brits will say “½ pint” (10 oz.), with the rest of the recipe being scaled accordingly, naturally. But, outside of home canning, many North Americans are losing an everyday understanding of what a pint is.

Brits will refer to ½ pints in places where Americans might refer to a cup. Note though that an American pint is approximately 500 ml, so half an American point is 250 ml / 1 cup. A British pint is approximately 600 ml, and therefore a British half pint is 300 ml. If you’re a North American working with a British recipe and you see ½ pint, measure 10 oz (300 ml.) If you’re a Brit working with a North American recipe and you see half a pint or 1 cup, measure 8 oz. (250 ml) in volume.

For everyday kitchen use purposes, you can figure on a standard 1 cup measuring cup as being 250 ml in the United States, Canada, New Zealand and Australia.

All that being said, with all the recipes that are now flooding across the pond from North America, as well as from Australia and New Zealand, Brits are exposed now to a great many recipes calling for volume measurements of solid ingredients.

In response to the need created by these recipes, you can now buy sets of measuring cups in stores such as Tesco’s that are approaching the North American measurements for a cup. On them you see marked ¼ cup (60 ml – Ed.: close enough), ⅓ cup (80 ml), ½ cup (125 ml), 1 cup (250 ml.) Nigella Lawson sells measuring cups in the exact same dimensions, shaped like tea cups, with the level line marked inside beneath the rim. Some, though, have noted that their lack of spout makes them hard to pour liquids out of, and having the level line beneath the rim makes them hard to level off dry ingredients with.

In the UK, many bread machines are shipped with cups for measuring flour, but it can be very hard otherwise to find such measuring cups there for levelling off at the top, even though bread maker machine instructions there will tell you to do so.

Brits who want to cook a lot of North American recipes are probably best to grab somehow a set of North American measuring cups, both liquid and dry.

Cups in older UK recipes

Informally, some older British home cooks did refer to cups for volume measurements of solids. But these cups were not a standard measuring cup created specifically for cooking: these were cups were designed expressly for drinking, and pressed informally into service for measuring purposes.

Elizabeth David, writing in the early 1960s, says:

“English teacups, breakfast cups and coffee cups used as measuring units make sense to us; there could hardly not be a teacup in the house, and, give or take a spoonful, its capacity is always about five ounces; a breakfast cup is seven ounces to eight ounces; a coffee cup is an after-dinner coffee cup, or two and a half ounces; but not to Americans, who are baffled by these terms in English cookery books. To them a cup is a measuring cup of eight fluid ounces capacity and there the matter ends. They don’t know what a teacup holds, nor what a breakfast cup looks like, and a coffee cup is a morning coffee cup, which might be a teacup or a breakfast cup, whereas an after-dinner coffee cup is a demi-tasse.” [1]David, Elizabeth. Measurements and Temperatures. In: Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen. London: Grub Street. 2000. E-edition.

Going by David’s guidance we therefore have

- After-dinner coffee cup: 2 ½ oz. (roughly a quarter of a US standard cup);

- Breakfast cup: 7 to 8 oz. (roughly ⅞ths of a US standard cup);

- Teacup: 5 oz. (roughly ⅔ of a US standard cup).

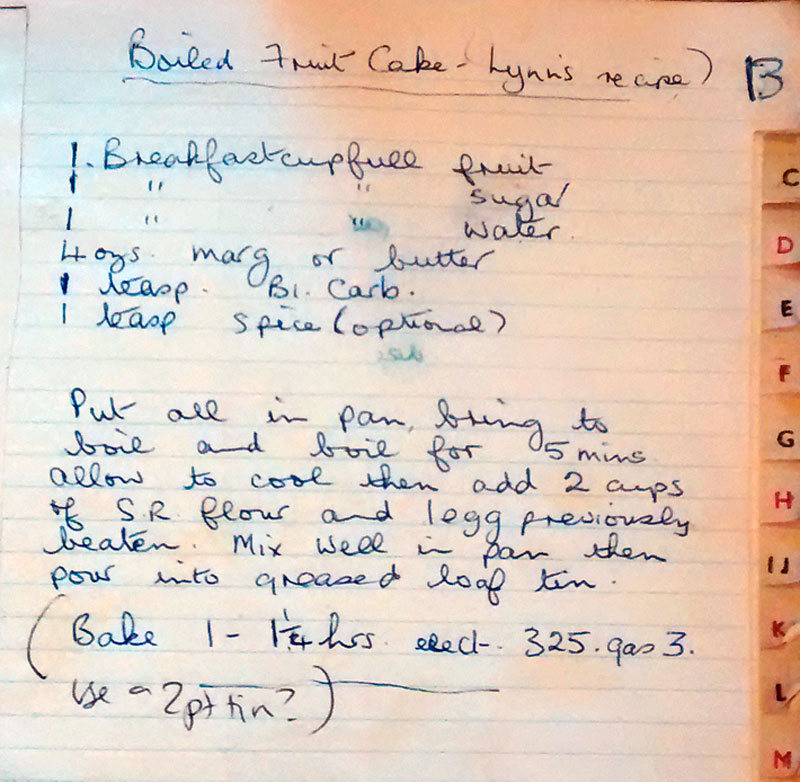

Here is a British recipe from approximately the mid-1900s calling for ingredients measured by breakfast cups:

Mid-1900s British recipe using measurement in cups. Note though that the butter is still weighed. © Calum Rogers

Nigel Slater, in response to a reader’s question, defines a breakfast cup as 200 ml (just under 7 fluid oz.):

“Q: When an old but very efficient recipe says to use a breakfast cup, what are the correct dry and liquid measurements to use in this modern age?

A: A breakfast cup was the sort you might use for a large milky coffee. The measurements are very much equal to an American measuring cup. So for any recipe specifying a breakfast cup you should allow 200 ml for a full one. Obviously with dry measures it will depend what you fill it with.” [2]Slater, Nigel. Ask Nigel. Manchester: The Guardian. 24 May 2009. Accessed August 2015 at http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/may/24/ask-nigel-slater-cooking-tips

Fanny Craddock conversions

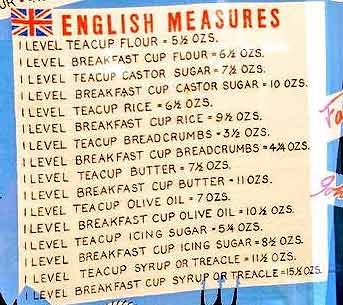

Fanny Craddock gave readers the following table for converting English cups to weights:

Fanny Craddock. Bon Viveur / Daily Telegraph.

Teacups

- 1 level teacup flour = 5 ½ oz.

- 1 level teacup castor sugar = 7 ½ oz.

- 1 level teacup rice = 6 ½ oz.

- 1 level teacup breadcrumbs = 3 ½ oz.

- 1 level teacup butter = 7 ½ oz.

- 1 level teacup olive oil = 7 oz.

- 1 level teacup icing sugar = 5 ¼ oz.

- 1 level teacup syrup or treacle = 11 ½ oz.

Breakfast cups

- 1 level breakfast cup flour = 6 ½ oz.

- 1 level breakfast cup castor sugar = 10 oz.

- 1 level breakfast cup rice = 9 ½ oz.

- 1 level breakfast cup breadcrumbs = 4 ¼ oz.

- 1 level breakfast cup butter = 11 oz.

- 1 level breakfast cup olive oil = 10 ½ oz.

- 1 level breakfast cup icing sugar = 8 ½ oz.

- 1 level breakfast cup syrup or treacle = 15 ½ oz.

French measuring cups

Elizabeth David felt that informal French cup measurements were very clear once you understood French tableware:

“Some of the best of old French recipes are the kind which specify ‘un bol de creme fraiche’ or ‘un verre de farine.’ Maddening until one twigs that the French have a different word for every kind of bowl they use, and that a ‘bol’ is not a salad bowl or a mixing bowl of unspecified capacity, but the bowl from which you drink your morning café au lait, in fact a cup; so to use it as a measuring unit is perfectly reasonable since every French household possesses — or did possess — such bowls, and their capacities, half-pint, near enough, vary little. (As with so many Cookery book measurements, this one probably came into being through national shopping habits. In remote and even not so remote country districts in France you still take your bowl or jug to the dairy to have it filled up.) Those glasses of flour, it can usually be taken, are tumblers of six-ounce capacity, because if French cooks mean a wine glass they say ‘un verre à Bordeaux’ and if they mean a small wine glass they say ‘un verre à porto’— a sherry glass to us. ” [3]David, Elizabeth. Measure for Measure. London: The Spectator. 15 March 1963. Page 29.

Measuring cups in other countries

In the UK, measuring cups are delineated in imperial pints and ounces, and in metric.

In Canada, the US, Australia and New Zealand, they are delineated in cups and ounces, and in metric. Larger ones will have US pints and US quarts on them as well. The cups for these countries are the same size: 8 oz / 250 ml.

In the rest of the world, generally, they are delineated in metric.

In Japan, a modern cup for kitchen measurements is 200 ml. There is also a traditional Japanese cup, called a “go”, which is about 180 ml. A “go” was used for purposes such as measuring rice, and sake. Sake bottles are 720 ml, which is four “go” ‘s of sake (4 x 180 ml.)

Some Mexican recipes still are given in cups (called “taza”), as in “¼ de taza de leche” (¼ cup of milk.) Dry ingredients may even be given by Mexican recipes in cups, which is likely the American influence.

Metric measuring cups

Some metric purists (usually scientists in English-speaking countries) bristle at the mention of “metric cups” or “metric teaspoons” saying that they don’t exist. And in their labs, that is correct: you’ll never see such a measure in labs that use metric.

The plain fact, however, is that home cooks do have metric measuring cups.

Even in metric countries, cooks at home often use cups for dry measure. Some measuring cups in Italy, for instance, have ml for liquid on one side, and g (grams) on the other for measuring the weight of flour based on its volume. Elsewhere in Europe, measuring cups often give ml measurements on one side, and various g equivalent marks for flour, rice, sugar, etc on the other side.

And two quotes from Australian government officials show that they certainly believe that a metric measuring cup exists:

- “A ‘cup’ is a standard metric cup (250 mL.)” [4]Lester, Ian H. Australia’s Food & Nutrition. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Government Publishing Service.

Appendix D, Page 312. 1994. - “The vast majority of data in this File comes from the original US Codebook files adjusted to metric measures, for example, US cup to metric cup. ” [5]Introduction to AUSTRALIAN FOOD AND NUTRIENT DATABASE ( AUSNUT 1999 )

Cooking Tips

If you have a scale, you can check to see how accurate your measuring cup is. On the scale, weigh out ½ pound of water. Pour into your measuring cup. The measuring cup should show exactly 1 cup / 8 oz.

References

| ↑1 | David, Elizabeth. Measurements and Temperatures. In: Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen. London: Grub Street. 2000. E-edition. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Slater, Nigel. Ask Nigel. Manchester: The Guardian. 24 May 2009. Accessed August 2015 at http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2009/may/24/ask-nigel-slater-cooking-tips |

| ↑3 | David, Elizabeth. Measure for Measure. London: The Spectator. 15 March 1963. Page 29. |

| ↑4 | Lester, Ian H. Australia’s Food & Nutrition. Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australian Government Publishing Service. Appendix D, Page 312. 1994. |

| ↑5 | Introduction to AUSTRALIAN FOOD AND NUTRIENT DATABASE ( AUSNUT 1999 ) |