Milk in bottles. J Garget / Pixabay.com / 2020 / CC0 1.0

The 8th of April, 1879, reputedly marks the date that milk was first delivered to customers at home in glass bottles.

Why not celebrate today by buying some milk in glass bottles? Though plastic makers point to the overhead of cleaning glass bottles, there’s a strong argument to be made that at the end of the day, glass bottles are still the better choice for the environment.

A couple of points about the historical basis of this day’s claim.

Home milk deliveries were happening before this reputed occurrence; just not in glass bottles.

And, having dug deep into this claim, CooksInfo found results that might cast its complete accuracy into doubt. But, it is certain that delivery of bottled milk to homes started happening around this date — perhaps a little before, but not by too much — so it could still be picked as a reasonable marker to note this little piece of progress in the food world!

The next big advance for milk would be pasteurization, but that’s another story.

#MilkInBottles

See also: Milk, Pasteurization, Anniversary of First Pasteurisation Test

Early home milk delivery

In the final quarter of the 1800s in the United States, home milk delivery became an important service. An increasing number of people wanting milk were living in cities, but city people couldn’t very well keep their own cows. A milk delivery service to them worked because of the density of cities: there were enough people on a route in a short space to make the service financially feasible for a business to offer. Plus, customers needed daily delivery as there was no refrigeration to allow milk to keep for long.

Before the arrival of milk delivered in bottles, milkmen would drive along with barrels of milk and customers would bring out their own containers or vessels and the milkmen would fill them from the barrel. This mode of delivery came to be seen as unhygienic, however.

Note as well that dairies had already begun offering milk for sale in glass bottles or jars — but this was on site at the dairies.

The concept of selling milk in bottles, let alone then transporting them great distances for delivery, had its detractors at first. Some thought the bottled milk was clinical looking, like drugstore medication. Others thought the bottles would be too fragile for the transportation first via rail then by carts on the rough city streets and roads at the time.

But customers came round to the idea, because it offered both convenience and hygiene. The glass would have allowed them to see the quality of the milk they were being delivered. They could visibly inspect to ensure that it was not curdled, that it contained no visible impurities such as dirt or straw, and, that it had a satisfactory quantity of cream on the top.

Early milk bottles

Before bottle-shaped bottles became standard, some dairies sold milk on site in Mason jars.

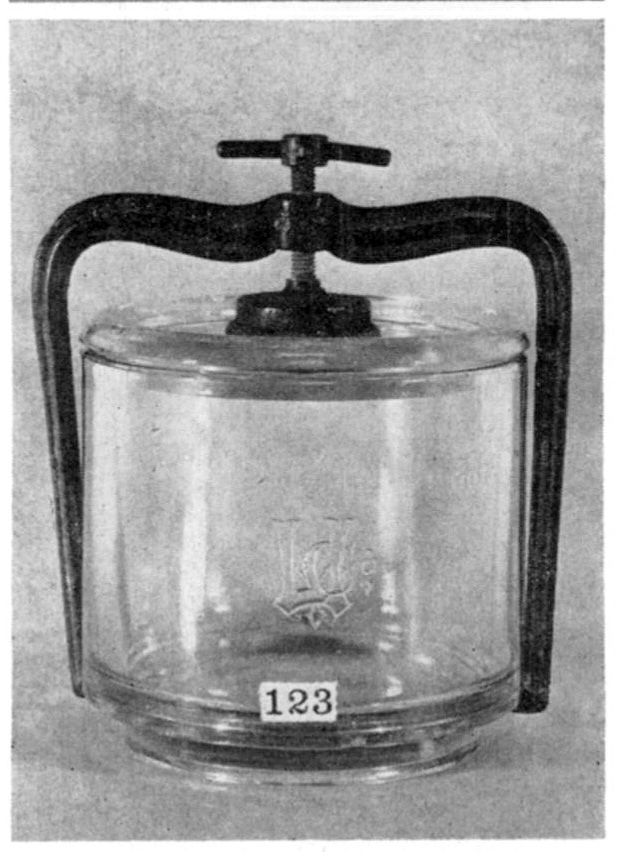

Two early designs of jars / bottles specifically for milk were the Lester Milk Jar (“The Lester Milk Jar was patented January 29, 1878. A screw clamp held the lid in place, but the entire container was awkward.”) [1]Lockhart, Bill. Dating Milk Bottles. Society for Historical Archaeology. 2014. Page 20. Accessed March 2021 at https://sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/ElPasoDairies/Chapter3-DatingBottles.pdf. and the Warren Milk Jar, made from 1879 until at least 1904. [2] Ibid.

Lester Jar. From: Gwinn, David Marshall. Four Hundred Years of Milk in America. New York History, vol. 31, no. 4, 1950, Page 454. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23149676. Accessed 26 Mar. 2021

A Maine Board of Agriculture report mentions these two types of jars / bottles being used to supply milk to New York City in 1881:

“There are some other methods of supplying New York with milk. There is the recent system introduced of putting milk in glass jars — the Lester Milk Co’s process or arrangement. This is a patent jar of glass which contains either one or two quarts and the milk having been cooled just in the manner I have spoken of, in tin coolers or cans, is drawn into these jars and an air-tight lid with an india-rubber band is pressed on with a screw, so that the milk shall be continually under pressure to avoid any shaking; then it is packed in boxes and if the box is kept right side up the cream rises in these jars; they are as large at the top as below and they can be opened and brought on to the breakfast table and the cream skimmed off by the lady at her own table, provided it has not been subjected to this process in the kitchen. The Warren Milk Company’s bottle is a large glass bottle with a large open mouth, and is more extensively employed than the Lester Milk Company’s jar, because the bottle is much cheaper than the jar.” [3]Maine Board of Agriculture. Twenty-fifth Annual Report for 1881. Sprague & Son, Printers: Augusta, Maine. 1882. Pp 106-107

Many different glass milk bottle / jar designs soon flooded onto the market, no doubt with each proponent hoping his or her design would be the one that really took off. Some were bail-type (aka “lightning”) closure systems with wire. Other closure systems included cardboard or foil stoppers.

Dairies would have their branding etched into the glass, for advertising. On the back, they would often also advertise their other products such as butter or cheese that the milk-purchaser might also be interested in.

Bottles being left at people’s homes also required an innovation in home design, as bottles were best left in a shady place so the milk would keep better. Along came milk boxes, either as built-in features of new homes, or as separate standalone insulated boxes on people’s porches for the milkmen to put the bottles into.

Milk box. Don Schwartz / Pixabay.com / 2010 / CC0 1.0

Within a few decades, glass bottling became a legal requirement in some areas for hygiene reasons.

Still, as with everything, worries about how true the promises actually were in practice crept in. People worried whether the glass bottles were being sanitized properly between uses. Stories were common of milkmen taking two used, as yet uncleaned, pint bottles that they had just picked up for return, and using them to split a quart of milk between the two bottles to meet a customer request.

Single-use milk containers

Single-use milk containers were felt by many to be more hygienic than re-usable glass bottles. They also, conveniently, spared dairies of the overhead and infrastructure required to collect, sterilize and re-use the bottles.

Waxed cardboard containers for milk started to appear as early as the 1890s. [4]Alfred, Randy. April 8, 1879: The Milkman Cometh… With Glass Bottles. Wired Magazine. 8 April 2010. Accessed March 2021 at https://www.wired.com/2010/04/0408first-glass-milk-bottles/

One problem with cardboard was that people couldn’t see the milk inside, to see how much cream they were getting:

“The use of paper bottles has not been too successful in this territory because of competitive conditions. The housewife is milk-conscious, and looks for the cream line.” [5]. Tolland, A.R. Report of Committee on Milk plant Practice. Health Department, Boston, Mass. Journal of Milk Technology. 1938. Vol. 1, issue 6. Page 38.

By the 1940s, waxed cardboard containers with peak roof tops became common. This design, though, had actually been around since 1915. [6]Alfred, Randy. April 8, 1879: The Milkman Cometh… With Glass Bottles. Wired Magazine. 8 April 2010. Accessed March 2021 at https://www.wired.com/2010/04/0408first-glass-milk-bottles/

Single-use plastic milk jugs started being introduced in the mid 1960s. In 1967, milk in plastic bags was introduced to the Canadian market.

The demise of delivery

Suburban sprawl made delivery routes longer and thinner and less financially feasible as a business model. Then supermarkets led to dwindling customers, making routes even more uneconomical.

Now, it is cheaper for dairies to load up a tractor trailer and deliver all the milk to one big grocery store.

Ironically, the vast spaces of suburbia might have enabled families to keep their own cow again, and avoid the whole question of milk purchase altogether, but that never occurred to them!

Clarifying the claim about first milk in bottles

Note that prior to 8 April 1879, milk was being bottled and sold at dairies themselves, and, milk was being delivered to people in cities. The claim for this day appears to be a combination of the two happening together: bottled milk being delivered.

A good deal of the response to the claim might depend on how one wants to distinguish bottles from jars — term usage as well as designs can blend, making distinction murky at times. Remember that in England, as well as in Australia and New Zealand, preserving food in jars is called “bottling.”

Questioning the claim

The standard claim is that home delivery of bottled milk occurred on the 8th of April, 1879.

A second claim is frequently added, which is that the company involved was Echo Farms Dairy of Litchfield, Connecticut, owned by a Frederick Ratchford Starr (1821-1889.

A researcher for the Connecticut Historical Board acknowledged the popular claim about Echo Farm being the first to distribute bottled milk, though without supporting it, or providing any date for that:

“The farm is believed to be the first in the country to distribute bottled milk commercially.” [7]Carley, Rachel. BARN RECORD Litchfield. 7 November 2008. Page 5. Accessed March 2021 at https://connecticutbarns.org/upload/state_reg/SR-barn_Litchfield_EastLitchfieldRd_43_No.11498.pdf

Sadly, CooksInfo has to question the claim on both grounds, company and date.

No one provides any backup for the 8th April 1879 date.

Here are advertisements, one next to the other, in the The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, that ran on 18 January 1879.

In the top advertisement, Echo Farm offers milk delivery in cans in January 1879.

In the advertisement directly underneath, the Lester Milk Company is offering delivery in glass jars in 1879.

Advertisements in: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. Saturday, 18 January 1879. Page 1, col. 7.

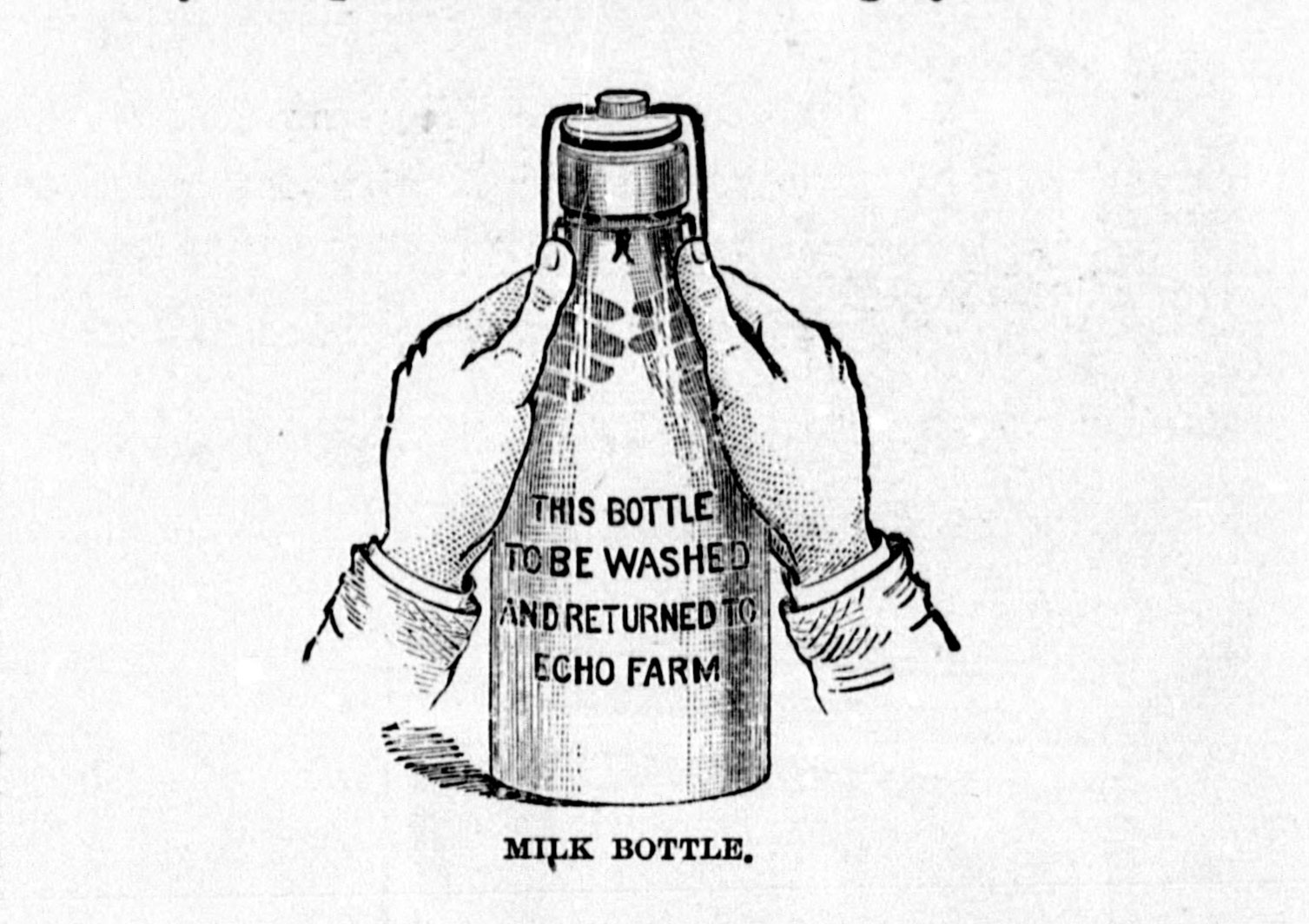

This advertisement is a reminder of what Lester’s glass jars looked like:

Lester Milk Jar Advertisement

Perhaps it is valid to say that Lester’s unique glass and metal clamp jars don’t technically (or even remotely) count as bottles. Disqualifying their contraption as a bottle would leave the field open for another contender to claim first milk bottle delivery — though we still don’t have any evidence that Echo Farm would have necessarily been the next one to pip past the post.

Echo Farms was certainly delivering milk in glass bottles by May 1879, and it’s reported as news:

“F.R. Starr of Echo Farm, Litchfield, is sending milk to New York, where he has established his own peddlers and milk route. He is milking about 80 cows. He puts the milk in glass bottles holding about a quart, with a patent stopper, which is nicely sealed. Each quart is marked with a nicely printed label on it, of the day it was sent, and in many cases with the name of the cow from which it was drawn.” [8]Local news column. In: Canaan Connecticut Western News. Canaan, Connecticut. 21 May 1879. Page 1, co1. 3.

Local news column. In: Canaan Connecticut Western News. Canaan, Connecticut. 21 May 1879. Page 1, co1. 3.

So sometime between January and May of 1879, Echo Farms did do a switch from cans to glass bottles.

In 1881, he writes that more than three years previous [so, 1877, 1878], he had been delivering milk in tin cans, and then sometime after that, switched to glass bottles. He didn’t note any claim to have been the first, or that he thought delivering the glass bottles was a big innovation on his part — though in his memoir, he’s not shy about stepping forward to point out other innovations he has made.

“I resolved more than three years ago to supply that want [of delivered milk]. Milk was sent from my dairy to those cities in one quart tin cans, and cream in pint and half-pint tin cans, all the cans being sealed here, and not opened until the seals wore broken at the residences of the consumers. Glass bottles were substituted for the tin cans…” [9]Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 95-96.

We’re not certain what design of milk bottles Echo Farms used in May 1879 but in 1881, a Maine Board of Agriculture report says that Starr was using the Warren design:

“Mr Starr of the Echo farm in Litchfield county is doing a very extensive business in shipping milk in these glass bottles of the Warren Milk Company.” [10]Maine Board of Agriculture. Twenty-fifth Annual Report for 1881. Sprague & Son, Printers: Augusta, Maine. 1882. Pp 106-107

This is what a Warren bottle looked like in an ad for the bottle:

Warren Milk Bottle ad (Crockery & Glass Journal 1879:16). In: Schulz, Pete, et al. The Dating Game. William Walton, the Whiteman Brothers, and the Warren Glass Works. Bottles and Extras. July – August 2010. Page 50. Access March 2021 at https://sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/Waltonwhitemanwarren.pdf

This is an illustration of the jar that Starr portrayed his glass bottle with, in his 1881 book. It matches the Warren bottle.

Illustration of Echo Farm milk jar / bottle. In: Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Page 100.

The Maine Board of Agriculture report mentions Echo Farm delivery to New York City in glass bottles in 1881, but also notes several companies are doing the same:

“There are several companies now engaged in delivering milk in these bottles [the Lester and the Warren designs]; it is put up at the farm in these bottles or it is put up in the city of New York, being transported there in tin cans and then put in the bottles, and delivered. Mr Starr of the Echo farm in Litchfield county is doing a very extensive business in shipping milk in these glass bottles of the Warren Milk Company.” [11]Maine Board of Agriculture. Twenty-fifth Annual Report for 1881. Sprague & Son, Printers: Augusta, Maine. 1882. Pp 106-107

A Connecticut reporter in September 1879 noted the transportation process for the Echo Farm milk:

“Mr F.R. Starr of Echo Farm sends 500 quarts of milk to New York daily, for which he receives ten cents a quart. The milk is put up in sealed glass jars. It is transported in a refrigerator wagon to the Naugatuck railway, where it is transferred to a refrigerator car.” — News of the State. Hartford, Connecticut: The Hartford Daily Courant. Thursday, 25 September 1879. Page 4, col. 1.

History of Echo Farms

Echo Farms was owned by Frederick Ratchford Starr (1821-1889). He wrote about it extensively in his memoir called “Farm Echoes” (published 1881).

Starr had previously been an insurance executive in Philadelphia, but his dream was to apply emerging scientific principles to agriculture:

“Starr, a Philadelphia insurance executive, came to Litchfield in 1869 in search of a country home to improve his health and began assembling parcels of land and old farms. He soon became fascinated by dairy farming and proceeded to educate himself and to recount his experiences in the memoir, Farm Echoes, published in 1881… [Echo Farm] consisted of about 400 acres and numerous barns and outbuildings. The farm is believed to be the first in the country to distribute bottled milk commercially. Starr shipped butter and milk to New York by train from the Bantam Depot… Starr died in 1889; [his wife] Henrietta Starr (b. 1821) and her daughter Maria (b. 1844) were living at the property in 1890… F. Ratchford Starr’s Echo Farm… represents the era of gentleman farming in the late 19th and early 20th century, when wealthy people turned to country life, with some individuals taking farming seriously and investing in the most current scientific agricultural facilities and techniques for breeding and dairy management. Starr participated in a popular literary genre in writing a memoir of his farm life.” [12]Carley, Rachel. BARN RECORD Litchfield. 7 November 2008. Accessed March 2021 at https://connecticutbarns.org/upload/state_reg/SR-barn_Litchfield_EastLitchfieldRd_43_No.11498.pdf

The farm’s milk came from purebred Jersey cows. Starr wrote:

“My herd consists of over one hundred and ninety Jerseys, and two superior prize cows of the Ayrshire breed with which I am experimenting in order to test their value as compared with Jerseys.” [13]Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Page 74.

Starr writes that before using bottles, he was actually sending milk to customers in tin cans that had been sealed right at the dairy:

“Luxuriating here in the purest and richest of cream and milk, and realizing that many thousands of the residents of New York and Brooklyn were actually suffering for the want of these blessings, I resolved more than three years ago to supply that want. Milk was sent from my dairy to those cities in one quart tin cans, and cream in pint and half-pint tin cans, all the cans being sealed here, and not opened until the seals wore broken at the residences of the consumers. Glass bottles were substituted for the tin cans, and there has ever since been such a demand for the milk and cream thus put up, as has exceeded my ability to supply it, though my herd has been more than doubled, and will probably soon be twice as large as now. By special agreement made with some reliable farmers in this neighborhood, thoroughly pure and rich milk in a limited quantity is received from them. They are bound by a written contract, duly signed and witnessed, to observe all the regulations deemed necessary to secure the best and purest milk, and from Jersey cows (frequently called “Alderneys”), so soon as the change from “native cows” can be effected.” [14]Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 95-96.

He describes his bottle filling and re-use methods:

“All the milk sent from this farm (except such as is known as special, being always from the same cow, and wanted for invalids and infants) is put into a large tank, made at an expense of several hundred dollars, because constructed of the best and purest materials. After being sufficiently cooled in this tank, which is surrounded by iced water so as to extract the animal heat as quickly as possible, the milk is drawn, twenty bottles being filled at the same time, through as many nickel-plated faucets. It is only in this way that consumers can have milk of unvarying quality. Every precaution that can be thought of is taken. All the milk is strained and re-strained most carefully. Each of the glass bottles in which it is shipped is sealed with a label upon which is printed the date it leaves the dairy. Twenty bottles are packed in a strong wooden box, which is locked before it leaves the dairy. These boxes are placed in a railroad car, which is locked by my men, and unlocked by the agents at New York. It will be seen by the picture of the bottles used, that the families who take the milk are required to wash them. This should be done as soon as they are emptied. Two, and sometimes three persons are kept busy at the agency washing them, as they are taken there by the men who distribute the milk, and five persons are kept actively employed in the dairy washing them as they are returned here. No bottle is used until it has thus been thoroughly cleansed. [15]Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 98-100.

Starr describes the cleaning facilities that are part of his milk bottling facility:

“The Dairy Building, also recently enlarged, now measures thirty-six feet by sixty-two feet, and is two and a half stories high. It contains on the first floor, a reception-room for visitors, who are admitted to the Butter Department on Wednesdays, Fridays, and Saturdays, from eleven o’clock A. M. until four o’clock P. M., churn-room, engine-room, room for washing tins, etc., three milk-rooms, one of which is a tank-room, and two rooms for milk and butter boxes. A large, well-aired cellar, with cemented walls and floor, is used for bottling milk. The second story contains a large room for milk boxes. These boxes are taken to this room as they are returned from New York and Brooklyn. Thence the bottles are carried to the wash-room adjoining. The boxes are then cleaned and got ready for use again. When needed they are lowered to cellar by elevator, from there they are sent by four two-horse teams to the railroad depot for transmission to New York and Brooklyn. The boiler-room connects with the dairy on the north, and hot-water pipes extend thence to every part of the dairy building, for heating and for washing purposes.” [16]Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 91-93.

One of his cow barns is still extant (as of 2021) at 43 East Litchfield Road and is listed with the Connecticut State Historic Preservation Office.

Further reading

Gwinn, David Marshall. Four Hundred Years of Milk in America. New York History, vol. 31, no. 4, 1950, pp. 448–462. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/23149676. Accessed 26 Mar. 2021. [Note: his 1868 date on the Lester jar delivery appears to be inaccurate.]

Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes (link valid as of March 2021).

Language notes

Milkmen look after milk, while milkmaids look after cows.

Sources

Carley, Rachel. BARN RECORD Litchfield. 7 November 2008. Accessed March 2021 at https://connecticutbarns.org/find/details/id-11498

Mussen, Dale. First Glass Milk Bottles. WYRK 106.5 FM. 8 August 2014. Accessed March 2021 at https://wyrk.com/first-glass-milk-bottles/

Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881

References

| ↑1 | Lockhart, Bill. Dating Milk Bottles. Society for Historical Archaeology. 2014. Page 20. Accessed March 2021 at https://sha.org/bottle/pdffiles/ElPasoDairies/Chapter3-DatingBottles.pdf. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Ibid. |

| ↑3 | Maine Board of Agriculture. Twenty-fifth Annual Report for 1881. Sprague & Son, Printers: Augusta, Maine. 1882. Pp 106-107 |

| ↑4 | Alfred, Randy. April 8, 1879: The Milkman Cometh… With Glass Bottles. Wired Magazine. 8 April 2010. Accessed March 2021 at https://www.wired.com/2010/04/0408first-glass-milk-bottles/ |

| ↑5 | . Tolland, A.R. Report of Committee on Milk plant Practice. Health Department, Boston, Mass. Journal of Milk Technology. 1938. Vol. 1, issue 6. Page 38. |

| ↑6 | Alfred, Randy. April 8, 1879: The Milkman Cometh… With Glass Bottles. Wired Magazine. 8 April 2010. Accessed March 2021 at https://www.wired.com/2010/04/0408first-glass-milk-bottles/ |

| ↑7 | Carley, Rachel. BARN RECORD Litchfield. 7 November 2008. Page 5. Accessed March 2021 at https://connecticutbarns.org/upload/state_reg/SR-barn_Litchfield_EastLitchfieldRd_43_No.11498.pdf |

| ↑8 | Local news column. In: Canaan Connecticut Western News. Canaan, Connecticut. 21 May 1879. Page 1, co1. 3. |

| ↑9 | Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 95-96. |

| ↑10 | Maine Board of Agriculture. Twenty-fifth Annual Report for 1881. Sprague & Son, Printers: Augusta, Maine. 1882. Pp 106-107 |

| ↑11 | Maine Board of Agriculture. Twenty-fifth Annual Report for 1881. Sprague & Son, Printers: Augusta, Maine. 1882. Pp 106-107 |

| ↑12 | Carley, Rachel. BARN RECORD Litchfield. 7 November 2008. Accessed March 2021 at https://connecticutbarns.org/upload/state_reg/SR-barn_Litchfield_EastLitchfieldRd_43_No.11498.pdf |

| ↑13 | Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Page 74. |

| ↑14 | Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 95-96. |

| ↑15 | Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 98-100. |

| ↑16 | Starr, F. Ratchford. Farm echoes. New York: Orange Judd Company. 1881. Pp 91-93. |