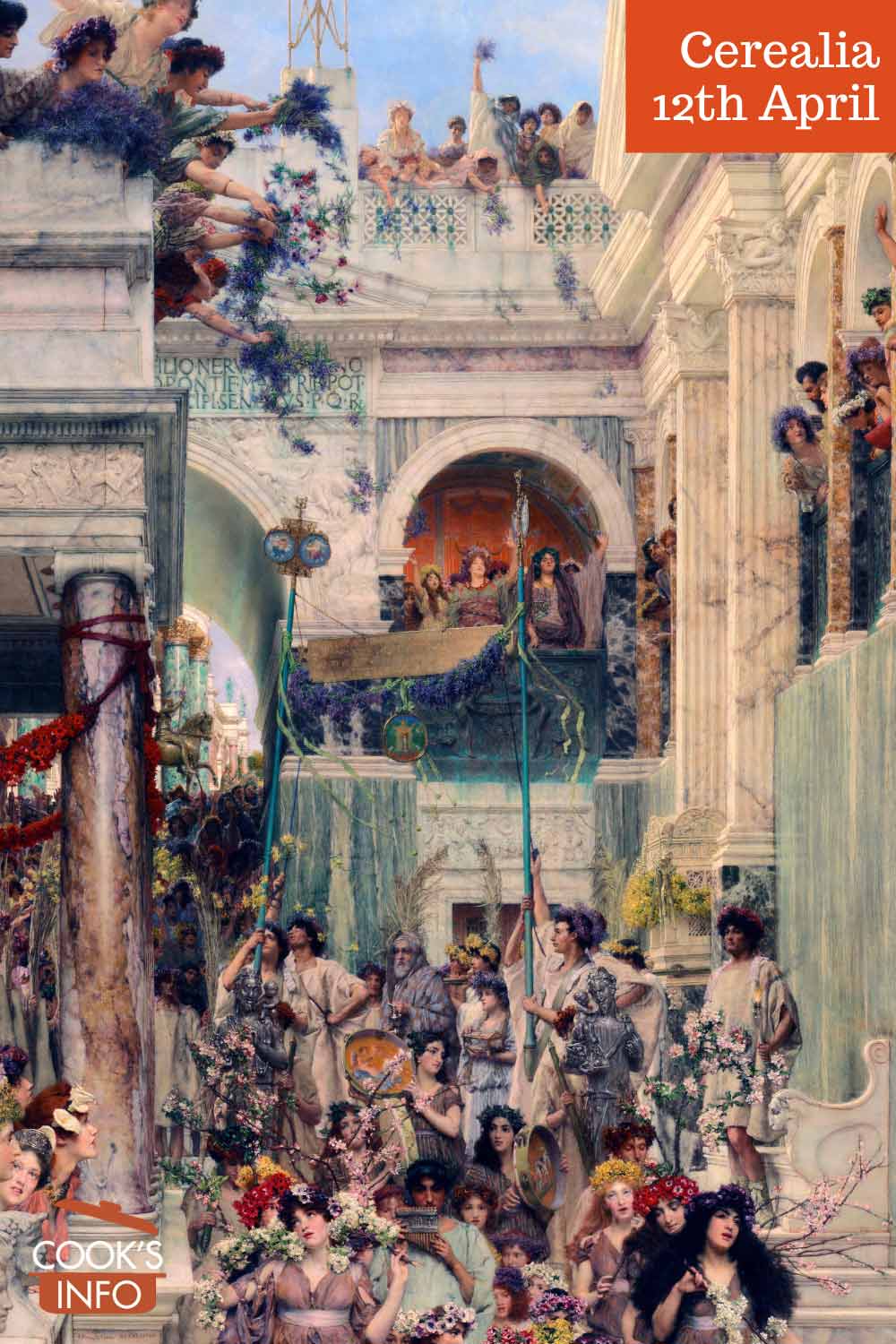

Cerealia festivities. Lawrence Alma Tadema / wikimedia / 1894 / Public Domain

The 12th of April is the start of Cerealia.

It was a Roman festival celebrated for many centuries to honour Ceres, the goddess of agriculture, grain and the harvest.

Ceres was also associated with bread, and fertility.

A temple was dedicated to her on the Aventine Hill in Rome circa 490 BC.

#CerealiaFestival #Cerealia

See also: Cereals, Ieiunium Cereris, Roman Food, Roman Holidays

Statue of Ceres in the Vatican Museums. Ty683g542 / wikimedia / 2005 / Public Domain

The festival

The festival would start on the 12th of April, and go on for several days:

“In ancient Rome, the festival of Cerealia was held on eight days in mid-late April, possibly the 12th-18th, with the actual festival day on the 19th.” [1]Roman festival of Cerealia at the Circus Maximus. The Colchester Archaeologist. 12 April 2016. Accessed April 2021 at https://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=26227

To honour her, there would be a procession of women dressed in white carrying pine torches. The torches symbolized Ceres looking for her daughter Proserpina, captured by Pluto. [2]”Lighting pine torches with both hands at Etna’s fires, she wanders, unquiet, through the bitter darkness, and when the kindly light has dimmed the stars, she still seeks her child, from the rising of the sun till the setting of the sun.” — Metamorphoses Book V (A. S. Kline’s Version) Bk V:425-486 [3] “There the goddess kindled two pine-trees to serve her as a light; hence to this day a torch is given out at the rites of Ceres.”– Ovid, Fasti, Book 4. PR. ID. 12th [455]. Frazer, James G., translator. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931.

At night during the festival, foxes with lit torches tied to their tails were released into the Circus Maximus. The speculation was that it was meant to represent foxes running through fields to cleanse the fields of vermin. Another legend held that it was to punish foxes for killing domestic chickens. [4]”He in a valley at the end of a willow copse caught a vixen fox which had carried off many farmyard fowls. The captive brute he wrapped in straw and hay, and set a light to her; she escaped the hands that would have burned her. Where she fled, she set fire to the crops that clothed the fields, and a breeze fanned the devouring flames. The incident is forgotten, but a memorial of it survives; for to this day a certain law of Carseoli forbids to name a fox; and to punish the species a fox is burned at the festival of Ceres, thus perishing itself in the way it destroyed the crops.” — Ovid, Fasti, Book 4. XIII. KAL. 19th [679]. Frazer, James G., translator. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931.

Games called the “Ludi Ceriales” featuring chariot races were held in Rome during this time at the Circus Maximus, near her temple on the Aventine Hill.

“Next come the games of Ceres. There is no need to declare the reason; the bounty and the services of the goddess are manifest. The bread of the first mortals consisted of the green herbs which the earth yielded without solicitation; and now they plucked the living grass from the turf, and now the tender leaves of tree-tops furnished a feast. Afterwards the acorn became known; it was well when they had found the acorn, and the sturdy oak offered a splendid affluence. Ceres was the first who invited man to better sustenance and exchanged acorns for more useful food. She forced bulls to yield their necks to the yoke; then for the first time did the upturned soil behold the sun. Copper was now held in esteem; iron ore still lay concealed; ah, would that it had been hidden for ever! Ceres delights in peace; and you, ye husbandmen, pray for perpetual peace and for a pacific prince. You may give the goddess spelt, and the compliment of spurting salt, and grains of incense on old hearths; and if there is no incense, kindle resinous torches. Good Ceres is content with little, if that little be but pure.” [5]Ovid, Fasti, Book 4. PR. ID. 12th [393]. Frazer, James G., translator. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931.

As the centuries went on, theatre performances (“Ludi Scaenici“) were added starting around 175 BC.

Ceres and her festivals were particularly popular with the Plebeian class:

“The Cerealia was an especially plebeian festival, and the plebs issued mutitationes, mutual invitations, to it. Moreover, the games of this festival, the ludi Ceriales, were celebrated by the aediles (magistrates) of the plebs…” [6]Spaeth, Barbette Stanley. The Roman Goddess Ceres. Austin, Texas: The University of Texas Press. 2010. Page 98.

It is uncertain when the festival finally died out; Christian suppression of age-old Roman religious traditions started in earnest in the mid 300s AD.

Modern-day Cerealia

In 2011, a modern cultural group started a revival of the Cerealia festival, holding it each year in a different Mediterranean country. They want to “revitalize ancient customs based on the respect for the earth and its bounty”:

“The event will be then, not only a moment of historical commemoration, but also of cultural exchange, thereby tackling issues such as nutrition, environment, economy, territory and social dimension, issues presented in the current context, which characterizes the varied world of grains. The social and economic importance of grains, essential components of the human food pyramid, is undisputed. Cerealia seeks to increase awareness on the value of land and of indigenous cultures, to renew ties between areas producing grains and consumers, and to revitalize ancient customs based on the respect for the earth and its bounty. The festival intends to promote the sharing of common challenges at the level of regional clusters among peoples overlooking the mare nostrum, stimulating the development of sustainable circular economy models and promoting the 17 SDGs of the UN 2030 Agenda, with a participatory bottom-up approach, which enhances the demands and skills of civil society, respecting and safeguarding of the Mediterranean ecosystem.” [7] Accessed May 2021 at http://www.cerealialudi.org/en/

Website: http://www.cerealialudi.org/en/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/CerealiaFest

Language notes

Ceres was known in Greek as ‘Demeter’.

References

| ↑1 | Roman festival of Cerealia at the Circus Maximus. The Colchester Archaeologist. 12 April 2016. Accessed April 2021 at https://www.thecolchesterarchaeologist.co.uk/?p=26227 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”Lighting pine torches with both hands at Etna’s fires, she wanders, unquiet, through the bitter darkness, and when the kindly light has dimmed the stars, she still seeks her child, from the rising of the sun till the setting of the sun.” — Metamorphoses Book V (A. S. Kline’s Version) Bk V:425-486 |

| ↑3 | “There the goddess kindled two pine-trees to serve her as a light; hence to this day a torch is given out at the rites of Ceres.”– Ovid, Fasti, Book 4. PR. ID. 12th [455]. Frazer, James G., translator. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. |

| ↑4 | ”He in a valley at the end of a willow copse caught a vixen fox which had carried off many farmyard fowls. The captive brute he wrapped in straw and hay, and set a light to her; she escaped the hands that would have burned her. Where she fled, she set fire to the crops that clothed the fields, and a breeze fanned the devouring flames. The incident is forgotten, but a memorial of it survives; for to this day a certain law of Carseoli forbids to name a fox; and to punish the species a fox is burned at the festival of Ceres, thus perishing itself in the way it destroyed the crops.” — Ovid, Fasti, Book 4. XIII. KAL. 19th [679]. Frazer, James G., translator. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. |

| ↑5 | Ovid, Fasti, Book 4. PR. ID. 12th [393]. Frazer, James G., translator. Loeb Classical Library Volume. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1931. |

| ↑6 | Spaeth, Barbette Stanley. The Roman Goddess Ceres. Austin, Texas: The University of Texas Press. 2010. Page 98. |

| ↑7 | Accessed May 2021 at http://www.cerealialudi.org/en/ |