Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge / wikimedia / Public Domain

Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge was a German chemist (8 February 1795 – 25 March 1867).

He discovered caffeine, as well as quinine, carbolic acid and coal tar dyes.

Early days

Runge was born in Billwerder, Germany, which today is in the Bergedoft district of Hamburg. He was the third child of seven or eight children. His father, Johann Gerhard Runge, was a Lutheran pastor; his mother was Catharina Elisabeth Heins. [1]There is a lot of conflicting genealogical information; it’s unclear whether there were 7 or 8 siblings, and varying dates are given for his parents’ deaths.

From 1810 to 1816, Runge was an apothecary apprentice at his uncle’s pharmacy in Lübeck [2]Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge. Brief bio at https://www.matthes-seitz-berlin.de/autor/friedlieb-ferdinand-runge.html. Accessed July 2019.. While working as an apprentice, he extracted atropine from henbane. He accidentally splashed some in his eye and discovered that it caused the pupil to widen — as women had done for centuries using the juice of berries from belladonna. He used atropine to induce temporarily the appearance of blindness in a friend, thus helping that friend avoid being drafted into the army.

One of his tutors, Johan Döbereiner, introduced him to Goethe in 1819. Runge demonstrated to him the effect of atropine on a cat’s eye. The poet Goethe, who was interested in botany, gave him in turn some coffee beans to use in his experiments.

“(After Goethe had expressed to me his greatest satisfaction regarding the account of the man [whom I’d] rescued [from serving in Napoleon’s army] by apparent “black star” [i.e., amaurosis, blindness] as well as the other, he handed me a carton of coffee beans, which a Greek had sent him as a delicacy. “You can also use these in your investigations,” said Goethe. He was right; for soon thereafter I discovered therein caffeine, which became so famous on account of its high nitrogen content.) [3] “Nachdem Goethe mir seine größte Zufriedenheit sowol über die Erzählung des durch scheinbaren schwarzen Staar Geretteten, wie auch über das andere ausgesprochen, übergab er mir noch eine Schachtel mit Kaffeebohnen, die ein Grieche ihm als etwas Vorzügliches gesandt. “Auch diese können sie zu Ihren Untersuchungen brauchen,” sagte Goethe. Er hatte recht; denn bald darauf entdeckte ich darin das, wegen seines großen Stickstoffgehaltes so berühmt gewordene Coffein.” — Runge, Friedlieb Ferdinand (1820). Neueste phytochemische Entdeckungen zur Begründung einer wissenschaftlichen Phytochemie [Latest phytochemical discoveries for the founding of a scientific phytochemistry]. Berlin: G. Reimer. pp. 144–159.

He initially called caffeine “Kaffebase” (“coffee base”). [4]Runge, Friedlieb Ferdinand (1820). pp. 144–159

In 1821, other chemists would isolate caffeine as well: Pierre Jean Robiquet, Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou.

Career and work

In 1819, Runge graduated in medicine from the University of Jena and in 1822 got a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Berlin [5]Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.britannica.com/biography/Friedlieb-Ferdinand-Runge.

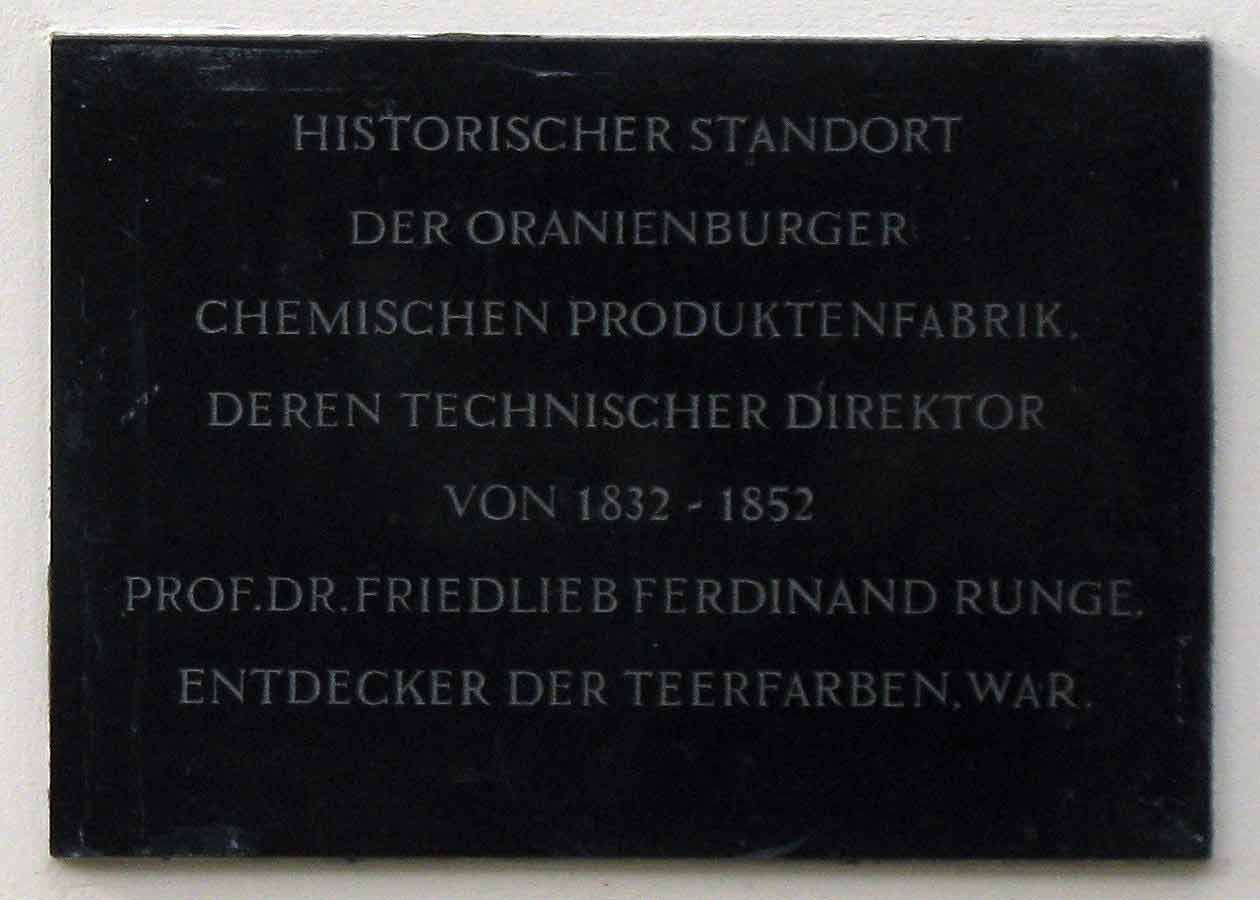

He taught at the University of Breslau and then in 1831 began work in a chemical factory (the “Chemische Produkten-Fabrik zu Oranienburg”) at Oranienburg, Brandenburg.

Historical location of the Oranienburger chemical products factory at 31 and 33 Rungestraße, Oranienburg. Judith Richmann / wikimedia / 2016 / CC BY-SA 4.0

At the chemical factory, he invented Rosölsaure (rose oil acid), the first synthetic dye. Then later blue, green and black synthetic dyes. He actually discovered many other things that the managers of the government-owned company were too short-sighted to see the value of: synthetic candles from processed tallow and artificial fertiliser made from abattoir waste were just some of them. The company told him to stop wasting time with his research, and eventually pensioned him off.

“Fifteen years before his death, Runge was fired after working at the company for more than 20 years. Despite his successes, Runge spent the last years of his life living in poverty and died at the age of 73 in 1867 Oranienburg, Germany. No cause of death for Runge is listed.” [6] Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge: The Man Who Gave Us Caffeine. New York, NY: Fortune Magazine. 8 February 2019. Accessed July 2019 at https://fortune.com/2019/02/08/friedlieb-ferdinand-runge-caffeine/

He never married.

Grave of Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge in Oranienburg. Jumbo1435 / wikimedia / 2011 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Other food interests

In his later years, Runge grew interested in food as he aged, and directed his chemical knowledge towards the science behind household problems, such as removing stains, making wines from fruits, canning meats and vegetables, and showing off his culinary skill at dinner parties. [7]Wong, Sam. Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge, the godfather of caffeine. London, England: New Scientist Magazine. 8 February 2019. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.newscientist.com/article/2193138-friedlieb-ferdinand-runge-the-godfather-of-caffeine/

He also discovered quinine, though others are usually given the credit. “In 1819, while still a student, Runge made another remarkable discovery for which he is seldom credited, isolating quinine from cinchona bark. The discovery of quinine, the first effective antimalarial compound, is usually attributed to Pierre Joseph Pelletier and Joseph Bienaimé Caventou, who reported their work a year later.” [8]Wong, Sam. Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge, the godfather of caffeine.

Plaque for Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge in Oranienburg. Doris Anthony / wikimedia / 2009 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Other legacies

Friedlieb-Ferdinand-Runge street in Leverkusen, Germany was named after him in 1937. (It had previously been named Paul Ehrlich Street. It was renamed because Ehrlich was Jewish.) [9]Friedlieb-Ferdinand-Runge-Str. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.leverkusen.com/strasse/index.php?view=Runge

The Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge Prize for unconventional art education was established in 1994 by the Stiftung Preussische Seehandlung. It is awarded every two years. [10]Art museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne. Press release. November 2017. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.kolumba.de/?language=eng&cat_select=1&category=51&artikle=712

The rungia family of plants has been named after him.

Sources

Beisswanger, Gabriele. Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge: Ein vielseitiger Erfinder ohne Fortüne. Stuttgart, Germany. Deutsche Apotheker Zeitung. 5 January 2012. DAZ 2012, No. 1, p. 88. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de/daz-az/2012/daz-1-2012/friedlieb-ferdinand-runge

Bennett Alan Weinberg, Bonnie K. Bealer, PH D Bennett Alan Weinberg, PH.D., Weinberg Bennet Psychology Press, 2001

Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.britannica.com/biography/Friedlieb-Ferdinand-Runge

Sella, Andrea. Runge’s pictures. In: Chemistry World. London, England: Royal Society of Chemistry. 1 August 2013. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.chemistryworld.com/opinion/runges-pictures/6445.article

The World of Caffeine: The Science and Culture of the World’s Most Popular Drug

Statue of Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge in Oranienburg. Doris Anthony / wikimedia / 2008 / CC BY-SA 3.0

References

| ↑1 | There is a lot of conflicting genealogical information; it’s unclear whether there were 7 or 8 siblings, and varying dates are given for his parents’ deaths. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge. Brief bio at https://www.matthes-seitz-berlin.de/autor/friedlieb-ferdinand-runge.html. Accessed July 2019. |

| ↑3 | “Nachdem Goethe mir seine größte Zufriedenheit sowol über die Erzählung des durch scheinbaren schwarzen Staar Geretteten, wie auch über das andere ausgesprochen, übergab er mir noch eine Schachtel mit Kaffeebohnen, die ein Grieche ihm als etwas Vorzügliches gesandt. “Auch diese können sie zu Ihren Untersuchungen brauchen,” sagte Goethe. Er hatte recht; denn bald darauf entdeckte ich darin das, wegen seines großen Stickstoffgehaltes so berühmt gewordene Coffein.” — Runge, Friedlieb Ferdinand (1820). Neueste phytochemische Entdeckungen zur Begründung einer wissenschaftlichen Phytochemie [Latest phytochemical discoveries for the founding of a scientific phytochemistry]. Berlin: G. Reimer. pp. 144–159. |

| ↑4 | Runge, Friedlieb Ferdinand (1820). pp. 144–159 |

| ↑5 | Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.britannica.com/biography/Friedlieb-Ferdinand-Runge |

| ↑6 | Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge: The Man Who Gave Us Caffeine. New York, NY: Fortune Magazine. 8 February 2019. Accessed July 2019 at https://fortune.com/2019/02/08/friedlieb-ferdinand-runge-caffeine/ |

| ↑7 | Wong, Sam. Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge, the godfather of caffeine. London, England: New Scientist Magazine. 8 February 2019. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.newscientist.com/article/2193138-friedlieb-ferdinand-runge-the-godfather-of-caffeine/ |

| ↑8 | Wong, Sam. Friedlieb Ferdinand Runge, the godfather of caffeine. |

| ↑9 | Friedlieb-Ferdinand-Runge-Str. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.leverkusen.com/strasse/index.php?view=Runge |

| ↑10 | Art museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne. Press release. November 2017. Accessed July 2019 at https://www.kolumba.de/?language=eng&cat_select=1&category=51&artikle=712 |