Bombay Sapphire

© Denzil Green

Gin is basically flavoured vodka. Its base, a neutral grain alcohol is made from rye, or corn, and malted barley.

For Gins in the category of London Dry, a ratio of 3 corn to 1 barley is considered good. The mash is distilled to around 90% alcohol, then reduced to 60% alcohol, then distilled again, with flavourings added this time.

The flavourings are called “botanicals” (as they are with many other alcohols.) Depending on the brand of Gin, they can include almonds, aniseed, angelica root, cassia bark, coriander, citrus peels, cubeb berries, grains of paradise, juniper berry, liquorice and orris.

In general, Gins are not aged (though there are exceptions.) Gins with higher alcohol content have far more flavour, because of alcohol’s ability to extract and carry flavour (as it does with extracts such as vanilla.) One of the strongest Gins is Plymouth Gin Navy Strength, at 57% alcohol.

Gordons

Fans think that Gordons is Gin as it is meant to be. Slightly aromatic, clean, but not refined to the point that it’s basically vodka. They think other more expensive, refined Gins are for wusses.

The taste comes through far better in mixed drinks, and makes a martini that says it has Gin in it. Gordons fans feel that more refined versions get away from the flavour of juniper, which is what Gin is all about.

There’s an urban myth that the first product placement in movies was Gordon’s Gin in The African Queen in 1951. In the movie, Humphrey Bogart’s character, Charlie Allnut, throws Gordons Gin down by the glassful almost as fast as Katharine Hepburn’s character Rose Thayer can throw it overboard by the caseful.

It wasn’t the first product placement, though. That may have been the Ford Model T in the silent, black and white Keystone Kops movie series, or Owl Cigars in the 1932 film “Scarface.”

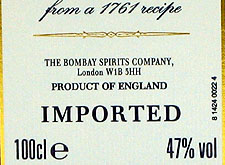

Bombay Gin

Export Strength Bombay

– © Denzil Green

Bombay is a slightly more expensive brand of gin, clean-tasting, with just a hint of the flavourings.

By its own description, it offers a “less ginny taste.” It uses only 10 flavouring ingredients.

It is made in two alcohol strengths: regular, being 40%, and export, being 47%.

Compound Gin

Also called “Gin with added gin concentrate”, or “Bathtub Gin.” Instead of being distilled with the botanical flavourings in it, flavouring extracts are added to a neutral alcohol. These are the cheaper gins.

London Dry Gin

Gin was brought to England from the Netherlands by English soldiers. Originally, it was much more heavily Juniper flavoured, and sweeter. In England, distillers worked out a drier, unsweetened version with a milder Juniper flavour which became known as London Dry style, which is a completely clear Gin. The Gin doesn’t have to be made in London to qualify as a London Dry Gin. Most gins that we know fall in this category, despite their brand names or place of origin: even Dublin Dry Gin and Cork Dry Gin are London Dry Gins. In fact, Beefeater is the only gin still actually made within London.

Golden Gin

A London Dry Gin that is aged briefly, about 3 months in charred oak barrels. It has a pale straw colour.

Old Tom Gin

Old Tom Gin is slightly sweetened, which makes it a very old style gin. Gins were originally sweetened to extend their shelf life. Someone who had the privilege of cracking open a bottle of Tanqueray that had been made in the early 1900s would be surprised at how sweet it had been made. The Old Tom type of Gin may not be being made any more.

Cooking Tips

Many swear by gin as a good marinade for game birds.

History Notes

Some hold that gin was invented by Dutch monks as far back as the 1100s. A more credible attribution, giving that had just barely been invented in the Middle East in the 1100s, is to a Dutch doctor called Franciscus de la Boe (1614 – 1672), who was a professor of medicine at Leiden University. He was also known for his study of Tuberculosis.

Juniper berries are a diuretic. Their oil was used medicinally, but it was very expensive. De la Boe was trying to create a cheaper alternative for patients by distilling the berries in alcohol. He came up with one medicine that patients couldn’t get enough of. By the end of the 1600s, gin had became popular as a cheap drink in the Netherlands.

Gin was introduced into England in the 1740s by soldiers returning from liberating the Netherlands and Belgium from French occupation. They had come to like it in the Netherlands; they called it “Dutch Courage”. By the second half of the 1700s, gin in England was so cheap that it was seen as a very low-class drink. That didn’t mean that the betters in English society didn’t drink it — they would just euphemistically ask for some “white wine”.

Gin was illegal in France until 1789, because Louis XIV (1638-1715) had given a monopoly on making strong alcoholic drinks to the makers of brandies. Until then, gin had to be smuggled into France. And it was.

Gin was originally sweetened to give it longer shelf life. Later, better distilling processes negated the need for the added sugar.

Americans preferred Dutch gin to English gin up until the end of the 1800s. [1]

Joan Crawford preferred Beefeater Gin.

Literature & Lore

“Now is the woodcock near the gin.” — William Shakespeare (26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616. Twelfth Night. Act II, Scene 5.)

“In winter, [the Queen Mother] often asked her equerry to pop in a tiny flask of gin. ‘I don’t approve of heated cars. They are very bad for your health. Many elderly people have caught pneumonia getting out of a heated car on to a freezing street. If one is cold when travelling, a nip of gin is a much more sensible idea.’ ” — Wyatt, Petronella. What’s in your bag, Ma’am? Apart from the chocolate, the plasters and the gin: Secrets of the Queen Mother’s handbag. London: The Daily Mail 2 September 2012.

“From the mid-eighteenth century, there had been a shift from gin, the historic drink of the people, to beer. Bad harvests and the 1751 Gin Act had made the spirit much more expensive, while the licensing laws for beer were being gradually loosened… [Despite that…] Gin palaces flourished with the arrival of gas lighting and plate-glass windows, making them a thing of wonder, places of light and warmth for those whose lives held little of either: undoubtedly, as Dickens observed, the poorer the neighbourhood, ‘the more splendid do these places become’. In 1835, amid the filth and despair of St Giles, he recognized that the gin palaces were ‘All… light and brilliancy … the gay building with the fantastically ornamented parapet, the illuminated clock, the plate-glass windows surrounded by stucco rosettes, and its profusion of gas-lights in richly-gilt burners, is perfectly dazzling when contrasted with the darkness and dirt we have just left. Soon the enormous gaslights outside became the distinctive marker of a gin palace. One such place in the Ratcliffe Highway, in the East End, had ‘a revolving light with many burners playing most beautifully’ over one door; over a second, ‘about fifty or sixty jets, in one lantern, were throwing out… brilliant gleams, as if from the branches of a shrub’; while a third had ‘no less than THREE enormous lamps, with corresponding lights.'” — Flanders, Judith. The Victorian City. London: Atlantic Books. 2012. Page 351 – 353.

Language Notes

The old name for gin was “genever”. This came from the Dutch word for “Juniper”, which in turn came from the French word, “genièvre”. In English, it was soon shortened to “gin”.

Sources

[1] “Next he [David Wondrich] adds the gin – it’s Dutch gin, usually called genever: Thanks to Wondrich’s research of New York City shipping records from the 19th century, we know that English gin did not become popular in the United States until the close of that century. We may presume, therefore, that the great Jeremiah P. Thomas, a.k.a. “Professor” Jerry Thomas, would have meant genever when he put gin in a recipe.” — McDowell, Andy. Old and Improved: Happily, the future of cocktail culture is also its distant past. Toronto, Canada: The National Post. 31 July 2009.