Life and Times

Rufus Estes worked for the Pullman company, as a chef looking after the unimaginably luxurious private Pullman railway cars that travelled across America in the second half of the 1800s. He had worked his way up from a porter. He later became a cookbook author.

His early childhood years were caught up in the American Civil War (1861-1865.) He was born in Murray County, Tennessee, in 1857. He was given the last name of Estes, because that was the last name of the man (D.J. Estes) who owned his family. He had two younger sisters, and six older brothers (two of which died during the American civil war) making for nine children in total.

In 1867, his family moved to Nashville, Tennessee to be with his grandmother where he was able to attend one term of school, while being expect to do many chores around the household. In 1873, at the age of 16, he started working in a restaurant in Nashville, and stayed there until he was 21. In 1881, he went to Chicago, where he worked for 2 years (it’s presumed he worked in a restaurant.)

In 1883, he began work for Pullman. He travelled between 1894 and 1897, going up to Vancouver and sailing as far as Tokyo. From 1897 to 1907 managed a private car for the United States Steel Corporation.

Over the course of his career, the people he managed a Pullman car for included American Presidents Benjamin Harrison (1889 – 1903) and Grover Cleveland (1884-1888, 1892-1896), Spanish Princess Eulalie (in 1893), Sir Henry Morton Stanley, the British explorer (of “Dr Livingston, I presume” fame), and Ignace Jan Paderewski (1860–1941), the Polish pianist and statesman.

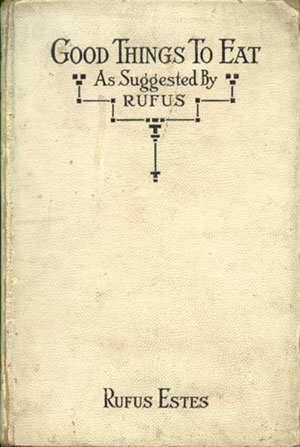

In 1911, he published his recipe book, “Good Things to Eat, as Suggested by Rufus: A Collection Of Practical Recipes For Preparing Meats, Game, Fowl, Fish, Puddings, Pastries, Etc.”, containing over 600 recipes.

The book shows the two halves of his personality, varying between his southern rural roots, and the elegant, private, ultra-rich world that he became a part of. He gives recipes to use up unripened tomatoes, grapes and melons that in the late fall would otherwise perish and go to waste when the frosts came. He gives fancy recipes that draw on truffles, clearly aimed at the carriage-trade. And, he gives some simple recipes that would be enjoyed by anyone: corncakes, fritters, steamed breads, crumpets, muffins, fried corn, and fried cauliflower,

He starts the book off with a “Hints to Kitchen Maids” section, in which you can tell he’s used to having staff to direct from his Pullman years — staff who knew the exact order in which Rufus expected things to be done:

“Breakfast–If a percolator is used it should first be put into operation. If the breakfast consists of grapefruit, cereals, etc., your cereal should be the next article prepared. If there is no diningroom maid, you can then put your diningroom in order. If hot bread is to be served (including cakes) that is the next thing to be prepared. Your gas range is of course lighted, and your oven heated. Perhaps you have for breakfast poached eggs on toast, Deerfoot sausage or boiled ham. One of the above, with your other dishes, is enough for a person employed indoors. When your breakfast gong is sounded put your biscuits, eggs, bread, etc., in the oven so that they may be ready to serve when the family have eaten their grapefruit and cereal.”

The disclaimer that he adds — “the above are merely suggestions that have been of material assistance to me” — makes it no less probable that his principles were more than “merely suggestions” for his staff.

He also gives at the start a page on weights and measures. He defines ¼ cup as being 4 tablespoons, as is now our standard. But while we define a standard tablespoon as being 3 teaspoons, as defined for us by Fannie Merrit Farmer in 1896, he divided a tablespoon into 4 teaspoons — thus, his teaspoon measurements were smaller than those defined by Fannie. Though by 1911 (15 years after the Boston Cooking School Cookbook) he may well have been aware of Fannie Merritt Farmer and her book (just as all cooking professionals still keep tabs on each other today), he may have decided that how he grew up defining a teaspoon was no less valid than how she did.

He had other clear opinions:

- he advocated cooking Yorkshire Pudding as one solid cake, rather than individual portions;

- he recommended his Black Currant Jelly recipe as a remedy for a sore throat;

- he felt that wild rice was best cooked in milk;

- “Fish should never be served without a salad of some kind.”

Only about 12 original copies of his books had survived by the time it was finally reprinted in 1999. The reprint edition contains 56 images from the period, that weren’t actually original to the 1911 edition.

While sometimes said to be the first black cookbook author, that was probably Abby Fisher, who published her cookbook in 1881, beating Rufus by 30 years.

Books

“Good Things to Eat, as Suggested by Rufus”: A Collection Of Practical Recipes For Preparing Meats, Game, Fowl, Fish, Puddings, Pastries, Etc. 1911.

History Notes

Good Things to Eat by Rufus Estes]”I was born in Murray County, Tennessee, in 1857, a slave. I was given the name of my master, D.J. Estes, who owned my mother’s family, consisting of seven boys and two girls, I being the youngest of the family.

After the war broke out all the male slaves in the neighborhood for miles around ran off and joined the “Yankees.” This left us little folks to bear the burdens. At the age of five I had to carry water from the spring about a quarter of a mile from the house, drive the cows to and from the pastures, mind the calves, gather chips, etc.

In 1867 my mother moved to Nashville, Tennessee, my grandmother’s home, where I attended one term of school. Two of my brothers were lost in the war, a fact that wrecked my mother’s health somewhat and I thought I could be of better service to her and prolong her life by getting work. When summer came I got work milking cows for some neighbors, for which I got two dollars a month. I also carried hot dinners for the laborers in the fields, for which each one paid me twenty-five cents per month. All of this, of course, went to my mother. I worked at different places until I was sixteen years old, but long before that time I was taking care of my mother.

At the age of sixteen I was employed in Nashville by a restaurant-keeper named Hemphill. I worked there until I was twenty-one years of age. In 1881 I came to Chicago and got a position at 77 Clark Street, where I remained for two years at a salary of ten dollars a week.

In 1883 I entered the Pullman service, my first superintendent being J.P. Mehen. I remained in their service until 1897. During the time I was in their service some of the most prominent people in the world traveled in the car assigned to me, as I was selected to handle all special parties. Among the distinguished people who traveled in my care were Stanley, the African explorer; President Cleveland; President Harrison; Adelina Patti, the noted singer of the world at that time; Booth and Barrett; Modjeski and Paderewski. I also had charge of the car for Princess Eulalie of Spain, when she was the guest of Chicago during the World’s Fair.

In 1894 I set sail from Vancouver on the Empress of China with Mr. and Mrs. Nathan A. Baldwin for Japan, visiting the Cherry Blossom Festival at Tokio.

In 1897 Mr. Arthur Stillwell, at that time president of the Kansas City, Pittsburg & Gould Railroad, gave me charge of his magnificent $20,000 private car. I remained with him seventeen months when the road went into the hands of receivers, and the car was sold to John W. Gates syndicate. However, I had charge of the car under the new management until 1907, since which time I have been employed as chef of the subsidiary companies of the United States Steel Corporation in Chicago.” — from Rufus Estes. Good Things To Eat, As Suggested By Rufus. Chicago: The Author. 1911. Page 7.

[Ed.: The “Booth and Barrett” that he mentions are Edwin Booth (1833-1893) and Lawrence Barrett (1838–1891), two American Shakespearian actors who teamed up from from 1866 to 1889, performing and touring in America and England. Edwin’s brother was the infamous John Wilkes Booth, who assassinated American President Lincoln.]

Literature & Lore

Green Tomato Pie: Take green tomatoes not yet turned and peel and slice wafer thin. Fill a plate nearly full, add a tablespoonful vinegar and plenty of sugar, dot with bits of butter and flavor with nutmeg or lemon. Bake in one or two crusts as preferred. — from Rufus Estes. Good Things To Eat, As Suggested By Rufus. Chicago: The Author. 1911. Page 7.

Green Melon Saute: There are frequently a few melons left on the vines which will not ripen sufficiently to be palatable uncooked. Cut them in halves, remove the seeds and then cut in slices three-fourths of an inch thick. Cut each slice in quarters and again, if the melon is large, pare off the rind, sprinkle them slightly with salt and powdered sugar, cover with fine crumbs, then dip in beaten egg, then in crumbs again, and cook slowly in hot butter, the same as eggplant. Drain, and serve hot. When the melons are nearly ripe they may be sauted in butter without crumbs. — Ibid., Page 68.

Green Grape Marmalade: If, as often happens, there are many unripened grapes still on the vines and frost threatens, gather them all and try this green grape marmalade. Take one gallon stemmed green grapes, wash, drain and put on to cook in a porcelain kettle with one pint of water. Cook until soft, rub through a sieve, measure and add an equal amount of sugar to the pulp. Boil hard twenty-five minutes, watching closely that it does not burn, then pour into jars or glasses. When cold cover with melted paraffin, the same as for jelly. — Ibid., Page 113.