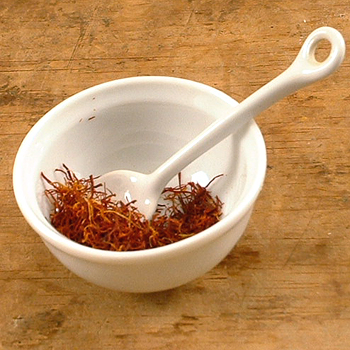

Saffron

© Denzil Green

Saffron is a spice which both colours and flavours food.

You can buy Saffron as threads or as a powder in glass vials or in tins at most food stores. Like all spices, the whole spice has a longer shelf life than ground versions. Good Saffron threads will be dry and brittle if you touch them, and should never smell musty. The threads, in their natural state, will have orangish or yellow tips, and are still expensive to buy like this. But for the most expensive threads, someone (whose life you won’t envy) sits there and snips these microscopic little colour bits off so that only the red parts are packaged.

You only need a few threads of Saffron in what you are making. A paella serving 8 people will likely only call for ¼ gram of threads. It’s not the kind of thing where a bit more is better: too much Saffron can turn what you are making into a mud-coloured, bitter-tasting concoction.

The Saffron plant is a member of the crocus family, which is cultivated for the sake of the stigmas of its flowers. Saffron is extremely expensive because it takes almost 13,000 stigmas hand-picked and dried from 4,300 flowers to make an ounce (28 g) of Saffron. People don’t wander the hills and dales, though, looking for a flower here and a flower there: the Saffron crocuses are cultivated 6 inches (15 cm) apart in rows in huge fields.

Spanish Saffron is touted as the best, though Spain is not the leading producer. Spain only produces 1 metric ton a year, while Iran produces 150 tons. Kasmir Saffron can be more expensive than Spanish.

Iran, in fact, claims that much of the Saffron it exports is imported by Spain, re-labelled and re-exported as Spanish at, of course, Spanish prices. Foodies claim that the more you pay for Saffron, the better it is. The Iranians counter basically that if you want to pay more for the same quality, then pay more: but given that what you’re paying for is all the middle-men and the packers, and not for better quality, you might well be buying their stuff direct. You will in fact see much pricey Saffron, with a label saying “Spanish Saffron; Spanish is the best in the world” with loads of yellow (lower-quality) threads mixed in.

As of 2004, you could expect to pay anywhere $35 to $100 US for an ounce (28 grams) of the pure all-red threads. But given that an ounce contains well over 10,000 threads, practically a lifetime supply for you, and your heirs and assigns, that much probably couldn’t be used up fast enough before it lost all flavour. That’s why Saffron is usually sold by stores in much smaller quantities, such as ½ grams ($4.00 US, 2004 price.)

Mexican Saffron is made from dried Safflower. It will give the right colour, but not the right taste expected.

Everyone who cooks tries Saffron at one point or another. Many people sum up their experience as, “It made stuff yellow and didn’t change their lives.”

Cooking Tips

Use the powder straight. Generally, recipes will have you steep the threads in a bit of hot water first because Saffron threads, like tea, release their flavour when “steeped”. Unless a recipe tells you otherwise, add Saffron near the end of the cooking.

Substitutes

Turmeric will colour a dish yellow, but not give the Saffron flavour. In fact, turmeric has its own flavour, which is quite pronounced, so go easy on it or your paella will turn into a curry. Safflower and annatto will give colour, but almost no taste.

Equivalents

1 gram of threads = approx 12 threads = 2 teaspoons of threads = 1 teaspoon crumbled = ½ teaspoon powdered

Storage Hints

Store in an airtight container in a dark, cool, dry place. After 6 months, the threads will start to weaken in flavour. The lifespan of the powdered Saffron is less. Storing in the freezer will prolong storage life further.

History Notes

Saffron was first cultivated in Kashmir and in Persia (Iran). The Persians used it both for food and for colouring clothes for the very rich.

The very wealthy among the Greeks and Romans, in addition to using it as a dye and flavouring, used it as a cosmetic and a perfume. Nero, who had a penchant for obscene excesses while his citizens starved (rather like our civil services today), had the streets of Rome sprinkled with Saffron when he passed through them. In the days when Britain was still Roman, Phoenician traders brought Saffron to Britain to trade it for tin from Cornwall.

When Spain was conquered by the Moors, who were Muslims from the Mid-East, the Muslims brought their love of Saffron to Spain and began planting it there around 960 AD.

San Gimignano, in Tuscany, well-known for its Medieval towers on a hill, also prides itself on its Saffron, which has been grown then since at least the late 1100s.

Starting in the 1400s, cloth merchants tried growing Saffron (to be used as a dye) around an area in Essex, which is still known today as Saffron Walden.

Literature & Lore

“Spikenard and Saffron; calamus and cinnamon with all the trees of Lebanon; myrrh and aloes with all the chief ointments.” — Song of Solomon iv. 14.

Homer refers to dawn as Saffron-coloured, and dresses gods and goddesses and heroes in Saffron-dyed clothing.

“I must have Saffron to colour the warden pies.” — Clown, The Winter’s Tale, IV, 3. Shakespeare.

Language Notes

The name Saffron comes from the Arabic “za’faran”, which means yellow.

Called “zafran kesari ” in Bengali.