Chestnuts for sale. Gerhard Gellinger / Pixabay.com / 2016 / CC0 1.0

Chestnut is a name used to refer to a category of high-starch nuts from Europe, North America and Asia. They are eaten cooked or prepared in some way, but not raw. The nuts grow inside prickly soft shells known as “burrs”.

Chestnut tree leaves are used to wrap some cheeses such as Banon in.

These have no relation to “water chestnuts.”

- 1 Chestnut varieties

- 2 Horse chestnuts

- 3 How to tell a true chestnut from a horse chestnut

- 4 Anatomy of a chestnut

- 5 Curing chestnuts

- 6 Buying chestnuts

- 7 Cultivating chestnuts

- 8 Small versus large chestnuts

- 9 Cooking Tips

- 10 Nutrition

- 11 Equivalents

- 12 Storage Hints

- 13 History Notes

- 14 Literature & Lore

- 15 Language Notes

- 16 Sources

- 17 Types of chestnut products

Chestnut varieties

There are three main species of trees producing edible chestnuts.

European chestnut

Edible chestnuts that we will see at markets and stores in the West mostly come from the castanea sativa or European chestnut tree.

In English, this tree is often referred to as the “Spanish Chestnut” tree. “The more specific name Spanish chestnut probably arose because the best chestnuts imported into Britain came from Spain.” [1]Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 198.

The European castanea sativa trees won’t grow much further north than Brittany in France.

European chestnut, Castanea sativa, showing leaves and burrs. H. Krisp / wikimedia / 2009 / CC BY 3.0

North American chestnut

The North American tree, castanea dentata, which produces edible chestnuts is sometimes referred to as the “Sweet Chestnut” tree.

There is actually also a second species, Castanea pumila (also known as American or Allegheny chinkapin) which can be found in the southern and eastern US states. It is a dwarf chestnut. Food encylopaedist Alan Davidson said that it has “small nuts of no commercial value, but of good flavour.”

American chestnut leaves and nuts. Peatcher / wikimedia / 2006 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Asian chestnuts

There are also Asian chestnut trees which produce smaller but sweet and edible chestnuts: castanea mollissima in China, and castanea crenata (aka Korean chestnut, Japanese chestnut) in Korea and Japan.

Both are resistant to chestnut blight.

Some cultivars have been selected for larger, choicer chestnuts, and some hybrids with the European chestnut have been created.

Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima). Kristine Paulus / flickr / 2018 / CC BY 2.0

Japanese / Korean chestnuts. Ant3202 / wikimedia / 2014 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Horse chestnuts

Horse chestnuts (Aesculus spp) are not edible, and are not actually related to the true chestnut trees discussed above despite the resemblance of the nut.

The horse chestnut, like the true chestnut, grows inside a shell known as a “burr”, but while true chestnuts have many fine hairs on their burrs, horse chestnuts have very far fewer but larger, stiffer, spikier bristles.

Horse chestnuts (Aesculus hippocastanum). Solipsist / wikimedia / 2004 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Horse chestnuts are not only inedible but are toxic. While they will not necessarily kill you, they will not do you any good.

“Horse chestnut contains significant amounts of a poison called esculin and can cause death if eaten raw.” [2]WebMD. Horse Chestnut. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-1055/horse-chestnut

Even cooked, toxins in the nut can cause serious medical issues.

Their name in English dates from the 1500s and comes from an erroneous assumption that the nuts were good medicine for certain ailments that afflict horses:

“The first written report on the horse chestnut is found in a letter that Willem Quackelbeen (1527-1561) wrote from Istanbul in 1557 to Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501-1578), a physician then living in Prague. Quackelbeen was at the time physician to Augier Ghiselin de Busbecq (1522-1592), ambassador of Ferdinand I, the Holy Roman Emperor, to Sultan Suleyman II, “the Magnificent,” under whose reign the Ottoman Empire had reached the climax of its political and military power, extending at that time through most of the Balkan peninsula and including all of what is now Hungary as well as parts of modern Romania, Slovakia, Moldavia, and Ukraine. Quackelbeen’s letter to Mattioli includes the following statement: “A species of chestnut is frequently found here [in Istanbul], which has “horse” as common second name, because devoured three or four at a time they [the horse chestnuts] give relief to horses sick with chest complaints, in particular cough and worm diseases.”” [3]Lack, H. Walter. “The Discovery and Rediscovery of the Horse Chestnut”. Arnoldia Magazine. Harvard University. 2002. Volume 61, Number 4. Page 15.

In fact, horse chestnuts are toxic to horses (as well as other livestock) and can make them very sick, affecting both the central nervous system as well as their gastrointestinal system. Visible symptoms may include tremors, convulsions, colic, weakness, and even coma. [4] Lewis, Lon D. et al. Feeding and care of the horse. Wiley-Blackwell. 1996.

Horse chestnut trees did, however, have another food association. Lager beer, which is bottom-fermented, requires cool temperatures to brew, which meant that historically it could only be brewed in the winters. Brewers in Germany, and particularly in Munich, Bavaria, hit upon the idea of creating vast beer cellars. During the winter, they stocked these cellars with ice from lakes and other sources. This kept the cellars cool enough during the summers to brew lager in. They built these huge cellars outside the city limits, where land was cheaper. Additionally, they planted horse chestnut trees above where the beer cellars were, to help shade the ground and keep some of the heat away. Horse chestnut trees were ideal in two senses: they have a dense, spreading, attractive canopy which provides optimal shade, and they have weak, shallow roots which would not damage the beer cellars underneath.

People began coming out of the city to the beer cellars to get beer, and would enjoy some while there right on the spot. In the summer, both the chilled beer and the shade from the horse chestnut trees provided relief from the summer heat. Soon, tables and chairs were set out, food served, and beer gardens were born. [5]Schaffer, Albert. 120 Minuten sind nicht genug. Frankfurt, Germany: Frankfurter Allgemeine. 21 May 2012. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/biergaerten-120-minuten-sind-nicht-genug-11759037.html

Horse chestnuts as famine food

The food encyclopaedist Alan Davidson writes of the horse chestnut tree:

“Its nuts, however, are bitter and inedible because of the presence of large amounts of tannins. These are soluble in water, so the nuts can be processed to produce an edible starch which, when ground to meal, makes a famine food.” [6]Davidson, Alan.

Archaeologists have found evidence of horse chestnuts in Korea and Japan being used in times of food scarcity as a food source, but only after having been subjected to complex acid removal techniques.

“In contrast to western Japan, deciduous acorns, as well as sapponic acid-rich horse chestnuts, were exploited in the Kanto and Chubu / Hokuriku districts of eastern Japan, during the Middle, Late and Final Jomon… In a pit at Shiho-dani Iwabuse, Fukui, a concentration of Aesculus turbinata remains was also found. It is commonly accepted among Japanese scholars, based on ethnographic studies, that deciduous acorns and horse chestnuts require complicated acid removal techniques, including boiling and ash-mixing procedures.” [7]Mason, Sarah L.R. Mason and Jon G Hather, eds. Hunter-Gatherer Archaeobotany: Perspectives from the Northern Temperate Zone. New York: Routledge. 2016.

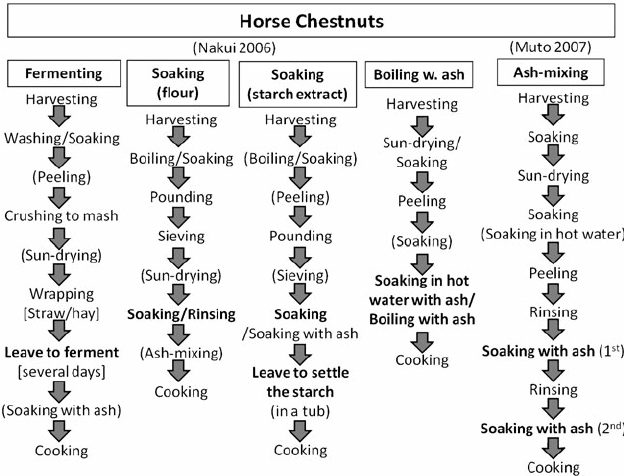

Leo Aoi Hosoya, in “Staple or famine food?”, discusses the complex, multi-step processes to remove sapponic and tannic acids that people in Japan and Korea subjected horse chestnuts (and acorns) to in times of famine to turn them into a food source. [8]Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 3(1):7-17 · March 2011). Available online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225633843_Staple_or_famine_food_Ethnographic_and_archaeological_approaches_to_nut_processing_in_East_Asian_prehistory

He provides this chart of what archaeologists think were some of the steps taken in the process:

Processing methods used for horse chestnuts by Koreans and Japanese in times of famine around 1,000–500 BC. Leo Aoi Hosoya: in Staple or famine food?

To be clear, the above points have been presented just to address the issue of possible historical consumption of horse chestnuts in times of famine. That people only seem to have practiced it in times of desperation is likely a reasonable indicator that from a culinary point of view, the results were not worth repeating when the scarcity ended. Our advice is to follow the recommendations of reputable medical doctors and avoid consumption entirely — both for people and for livestock.

How to tell a true chestnut from a horse chestnut

It’s easy to tell a true chestnut from a horse chestnut while they are in their burrs (“soft green shells”) — just look at the “spikes” on them. A true chestnut will look like a hedgehog or sea urchin; while a horse chestnut has far fewer, shorter spikes that grow out of small “warts.”

Once the nuts are outside their burrs, look for a tuft (“houpette” in French) at the top of the chestnuts, or a small point where one might have been. True chestnuts will have a tuft; horse chestnuts will not.

This short video is in French but the visual should still convey the idea.

“Both horse chestnut and edible chestnuts produce a brown nut, but edible chestnuts always have a tassel or point on the nut. The toxic horse chestnut is rounded and smooth with no point or tassel.” [9]Lizotte, Erin. What’s the difference between horse chestnuts and sweet chestnuts? Michigan State University Extension. 9 October 2019. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/whats_the_difference_between_horse_chestnuts_and_sweet_chestnuts

Anatomy of a chestnut

The fleshly skin that covers a chestnut is called a “burr.” The burrs of edible chestnuts are covered in fine bristles. Some of the burrs will crack on the tree or when they hit the ground; others have to be cracked manually.

Once out of the burr, chestnuts still have a bitter skin that must come off before eating. This skin will crack when roasted or can be more easily peeled off when blanched.

True chestnuts, showing finer spikes on burr. Federico Maderno / Pixabay.com / 2019 / CC0 1.0

Curing chestnuts

After harvesting, chestnuts need to be cured. This means allowing them to stand to allow starches in the nuts to convert to sugars, sweetening the taste.

Letting this process happen slowly over a couple weeks in a cool place (0 to 4 C / 32 – 40 F) is the best way to ensure a longer quality storage life for the chestnuts afterward. However, it can be sped up by storing the freshly-harvested chestnuts just at room temperature for a few days. The downside to this speed, though, is that “room temperature conditions will also dehydrate the chestnuts and so they will need to be consumed in a timely manner.” [10]Lizotte, Erin.

Buying chestnuts

Most fresh chestnuts (meaning not canned, jarred or frozen) that you will see at North American stores and markets are imported from Europe. Some small amounts of North American castanea dentata chestnuts are starting to coming back on the market as of 2015 or so (see History below.)

Chestnuts are almost always sold out of their spikey burr. When buying fresh chestnuts, choose chestnuts that are deep, consistent brown and shiny.

The University of Michigan Extension recommends this squeeze test:

“A ripe chestnut should have a slight give when squeezed, indicating they have been properly cured. A rock hard chestnut may require more curing time. A chestnut shell with a great deal of give indicates it is past its prime and has become dehydrated or has internal disorder.” [11]Lizotte, Erin.

The University of Michigan also suggests that ideally, for optimum quality, the store will be storing them in a chiller.

Avoid any chestnuts with pinholes which is a sign of worms.

You can get frozen, already peeled chestnuts that are more convenient to cook with. The peeling is done by machines that are made in Italy by companies such as Boema. Peeling chestnuts in any quantity can be very, very fiddly, frustrating and time-consuming.

Cultivating chestnuts

Chestnut trees, to produce effectively, have to be managed like orchards. You need other chestnut trees nearby for pollination. Each tree will put out male and female flowers, but they tend to pollinate only with flowers from another tree. The trees have to be tended. The best chestnuts come from trees that are grafted.

The trees start producing nuts when they are 15 years old, and get into their production prime when they hit 50 years old.

The trees can also be grown for their wood.

Different kinds of chestnuts : 2 lines on top are hybrids of Castanea sativa and C. crenata (french cultivars called Marigoule and Bouche de Bétizac) 2 lines below are from left to right : Castanea mollissima, wild sativa (2 and 3) and last is an Sativa/Crenata hybrid cultivar called “bournette”. Abrahami / wikimedia / 2010 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Small versus large chestnuts

Two types of chestnuts come from the European castanea chestnut tree. The same tree will produce both types of chestnuts, at the same time. We don’t really have words that make the distinction in English, so we must rely on French words.

The most common type of chestnut produced by the European chestnut tree is called in French “châtaigne” (“castagna” in Italian.) These grow two or three together inside their burr, divided from each other by a membrane. Each nut is flat-sided and small, only about 2 to 3 cm (an inch) or so big. Street vendors prefer these smaller “châtaigne” chestnuts, because they can fit more in a bag. They are also cheaper and therefore more suited price-wise to be a snack food.

The other type of chestnut produced by the European chestnut tree is called in French “marron.” Inside the burr, the nut grows as a single undivided whole kernel to fill the whole burr. The nut is rounded, and about 4 cm (1 ½ inches) wide. In addition to being larger than the “châtaigne” type, they are also sweeter, being about 15% sugar.

These have always been considered more desirable and are consequently more expensive. While the “châtaigne” type would in the past be used for animal feed, especially for pigs, “marrons” would never be fed to animals as they were too valuable.

The marron type are the ones used for marrons glacés.

If more than 12% of the chestnuts that a tree produces are “châtaignes”, the tree is called a “châtaignier.” Otherwise, it is called a “marronier.” Chestnut trees can be encouraged to produce more “marrons” than “châtaignes” through grafting and careful tending.

Cooking Tips

Chestnuts have thin shells compared to most other nuts. Consequently, there isn’t as much wastage with them as there is with other nuts. After shelling, they should still weigh about three-quarters of the weight before you started if you had success in peeling them easily.

When fresh, they can be roasted, baked, boiled, or steamed, but they need to be cooked in some way before consuming.

Chestnuts and turnip. Max Straeten / morguefile.com

Peeling lots of chestnuts is a real pain and a not very happy way to spend Christmas Eve getting them ready to be used as stuffing the next day. To make them easier to peel, you can freeze them first. Or place them in a pot, cover with water and bring to the boil. Then remove from the heat and drain. Remove the shells and then rub off the skin that will remain over the nut (you may wish to use a tea-towel or a piece of good quality paper towel to do this with). The skin is bitter, so you want to get it off. (Or, to avoid all that, snag the last bag of frozen, ready-to-use ones.)

To roast chestnuts, you need to make a way for the steam to escape so that they don’t explode. Place a chestnut on a cutting board flat side down, so that it won’t roll. Make a short slash in the skin with a serrated knife (any knife will do, but serrated is easier and is safer as it will slip less), or poke them with a fork. Bake on a baking sheet in oven at 200 C (400 F) for 10 minutes, or at 150 C (300 F) for 20 minutes, or until the skins split and the nut inside just starts to brown. Remove from oven, let cool until you can handle them safely and comfortably. Peel both the shell and the brown papery skin underneath, which is bitter. Don’t let them get too cold before you peel them, or it becomes very hard to remove the brown skin. If you are roasting a lot at once, you will have to move fast before they cool off on you. If they do, zap them in the microwave for 30 seconds or so.

Chestnuts roasting in South Tyrol. Matthias Böckel / Pixabay.com / 2018 / CC0 1.0

To “roast” chestnuts in the microwave, make a slit in them as per above. Zap a few chestnuts at first on high for 2 minutes until you figure out the right time for your microwave.

Here is further advice from the University of Michigan Extension service:

“Chestnuts may be roasted in the oven, over a fire or even in the microwave. To roast chestnuts, be sure to score through the shell to ensure steam can escape and to prevent a messy and loud explosion. Scoring halfway around the equator works very well. Generally, it takes around 20 minutes in a 150 C / 300 F oven.

For microwaving, the time can be as little as 2 minutes. Cook times can vary by microwave and oven, so some trial and error may be necessary and wrapping several nuts in a wet paper towel before microwaving works well. You can also try roasting them over an open fire or grill—though technically nestling them in the embers is best to prevent scorching. Depending on the temperature of the embers, this process can take anywhere from 15-30 minutes.” [12]Lizotte, Erin.

Fully-cooked nuts should be tender, sweet and should in theory peel easily. Be sure to allow the chestnuts to cool before handling.

To blanch chestnuts, boil for 4 minutes, then drain, wrap in a tea towel and squeeze them hard to pop the shells.

Chestnuts can also be boiled or steamed. Here are directions from the Chestnut Growers Inc. cooperative in Michigan:

“Boiling is an easy method of cooking chestnuts. First, cut them in half with a sharp knife, or score them. Boil for 10-15 minutes. As the opening enlarges, on the scored type, or ‘smiles yellow’ at you, they are ready to be removed from the water. It’s best to take out one or two nuts at a time, and peel them out of their shell and inner pellicle. If they start to cool too much, peeling will be more difficult. The longer nuts are cooked, the more they will crumble more upon removal from their shell.

Steaming is also another satisfactory method to cook chestnuts. Score them, or cut in half, and initially steam them for 10–15 minutes, adjusting cooking time to your eating preference. Carefully, remove them, as in the boiling instructions above, and use as intended.” [13]Chestnut Fresh Cooking Instructions. Chestnut Growers Inc.. Michigan. Accessed January 2020 at http://www.chestnutgrowersinc.com/about.shtml

Cooked chestnuts can be used as stuffing for poultry or made into purées. Sliced chestnuts with Brussels sprouts is an English classic, as is chestnut stuffing in roasted grouse.

Cooked chestnuts will split and “smile yellow at you. deluxtrade / pixabay.com / 2010 / CC0 1.0

Nutrition

Chestnuts are one of the lowest fat nuts. They are only 2 per cent fat (compared with 73% fat for macadamia nuts). “Chestnuts contain more starch and less oil than most other nuts and have had a special role as food for this reason. The European chestnut was formerly a staple food of great importance, but has now become more of a luxury.” [14]Davidson, Alan.

- 100 g fresh chestnuts: 199 calories;

- 100 g dried chestnuts: 371 calories.

A heavy diet of chestnuts leads to flatulence.

Horse chestnuts are inedible and dangerous to eat.

Equivalents

- Châtaigne: 100 nuts per 1 kg (2 ½ pounds).

- Marrons: 40 – 50 nuts per 1 kg (2 ½ pounds).

Storage Hints

European farmers with good storage conditions say chestnuts can be stored for up to three months — that’s what got many Europeans through the winters over the centuries. But sadly, none of us have root cellars anymore which provide those ideal storage conditions for many types of produce.

Fresh chestnuts in their shell stored at room temperature should be used up within a week.

The University of Michigan recommends fridge storage:

“When you get your chestnuts home, keep them cold but do not let them freeze (Due to their sugar content, chestnuts do not freeze until 28 F [-2 C] or below.) Store them in the produce compartment of your refrigerator where well-cured chestnuts can last for a few weeks. Ideally, place them in a plastic bag with holes made with a fork or knife to help regulate the moisture levels. If nuts are frozen, use them immediately after thawing.” [15]Lizotte, Erin.

Beyond those few weeks, chestnuts can be preserved by drying, pickling, or freezing.

Dried, they are usually made into flour but can also be soaked or steamed to rehydrate them for other uses.

There are no modern, tested recipes for pickling, only traditional ones: be sure any recipe used has a brine that contains at least 50% if not more of vinegar that is 5% acidity or higher, has a simmering process to both soften the chestnuts and drive the acidity inside them, and gives a heat processing time for the sealed jars.

To freeze, slit the chestnuts first so that they are ready to roast when you take them out of the freezer (if roasting is what you think you’ll be doing with them).

History Notes

Chestnut trees have been grown in China possibly since 4,000 BC and in Japan since the first millennium.

The Greeks were probably the first Europeans to grow the European chestnut trees. “The European chestnut, despite its name, is of West Asian origin. Around 300 BC the Greek writer Xenophon described how the children of Persian nobles were fed on chestnuts to fatten them; and it was the Greeks who brought the tree to Europe, from Sardis [Ed: capital of Lydia] in Asia Minor.” [16]Davidson, Alan.

The Romans were deliberately cultivating these trees by 37 BC. It was probably they who introduced them into Britain. Virgil mentions chestnuts three times in his pastoral poem, “Eclogues.”

- “Yet this night you might have rested here with me on the green leafage. We have ripe apples, mealy chestnuts, and a wealth of pressed cheeses…”

- “My own hands will gather quinces, pale with tender down, and chestnuts, which my Amaryllis loved..”

- “Here stand junipers and shaggy chestnuts; strewn beneath each tree lies its native fruit…” [17]Virgil. Eclogues, Georgics, Aeneid. Translated by Fairclough, H R. Loeb Classical Library Volumes 63 & 64. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1916.

The Romans would grind dried chestnuts into a flour and often mixed the resultant flour with wheat flour. They also commonly cooked chestnuts with lentils.

Some Medieval farmers in England grew chestnuts, but whether the nuts were small ones (châtaignes) or or the more valuable large ones (marrons), they were used mainly either for livestock food or for grinding into flour. The British growers didn’t really distinguish between the two kinds of nuts, the way that Europeans did. In the 1600s, the writer John Evelyn complained that the English still hadn’t learned to value chestnuts properly:

“But we give that fruit to our Swine in England, which is amongst the delicaces of Princes in other Countries; and being of the larger Nut, is a lusty, and masculine food for Rustics at all times. The best Tables in France and Italy make them a service, eating them with Salt, in Wine, being first rosted on the Chapplet; and doubtless we might propagate their use, amongst our common people…” [18]John Evelyn, Sylva, Chapter 7, “Of the chess-nut”, 1664.

Chestnuts were an important source of food all throughout the Dark and Middle Ages to many in areas such as Italy, Spain, Portugal and France. The trees would conveniently thrive in mountainous areas, which would have been well drained, which the trees like, and where not much else would grow. The poor would gather the chestnuts from the forests to eat, or would let their pigs graze on the chestnuts on the forest floor. Peasants who were reliant on chestnuts would often eat between 1 and 2 kilos (2 ½ and 5 pounds) a day during the winters. “Chestnuts have considerable food value. 1 ½ kg (3 ¼ lbs) supply sufficient calories to satisfy the needs of an average person.” [19]New Larousse Gastronomique. Paris: Librarie Larousse. English edition 1977. Page 217.

Marrons, however, when gathered, would be sold to the richer town folk as a cash crop.

Polenta was made with among other things, chestnut meal, before corn was discovered and brought to Europe.

Chestnuts began to decline in popularity in France as a food staple as wheat became more affordable from about the mid 1700s.

Parmentier, who helped to popularize potatoes in France, felt in 1780 that marrons would be a promising source to manufacture sugar from, but Napoleon chose instead to back research into sugar beets.

Many chestnut trees were destroyed in Europe by very hard winters in 1709, 1789 and 1870, and again between 1840 and 1860 by the “ink” blight.

American chestnut tree blight

A blight in the 1930s killed most of the native North American chestnut trees (castanea dentata) that bore edible chestnuts (“Sweet Chestnut Trees”). The blight arrived on chestnut trees imported from Asia.

“The American chestnut, C. dentata, once a common tree, especially in the Appalachians, bore excellent nuts, richer in oil than European chestnuts. The tree was widely cultivated until the 20th century, when chestnut blight almost wiped it out.” [20]Davidson, Alan.

Though over 3 ½ billion trees were destroyed, the North American trees are now slowly making a comeback in several states.

In 2001, a “Chestnut Growers, Inc.” cooperative was established in Michigan, and its members are open for business, selling American chestnuts. Their work is being supported by ongoing research being done by Michigan State University.

The U.S. Army Environmental Command wrote this in 2009 on a post of a seedling on flickr:

“During the past 20 years, the American Chestnut Foundation has bred chestnuts from the few remaining “mother” trees that survived the blight of the early 1900s crossed with the blight-resistant Chinese chestnut (Castanea mollissima). Slowly, these hybrids are being bred back to pure American chestnuts in order to produce trees that are over 90% genetically American, but that have picked up the crucial genes necessary for blight resistance, with the goal of producing a tree that can be reintroduced to its native range and thrive. Volunteer Training Site-Catoosa (VTS-C) has become a significant partner in this effort with its new chestnut seedling orchard.” [21] U.S. Army Environmental Command. Flickr post. 15 July 2009. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.flickr.com/photos/armyenvironmental/4443191356

American chestnut seedling. U.S. Army Environmental Command / flickr / 2009 / CC BY 2.0

At this early stage, though, the Americans aren’t yet distinguishing between châtaignes and marrons. They are all châtaignes and just sold as chestnuts.

If the trees survive the blight (which is still present), their next challenge will be to re-introduce chestnuts to the everyday North American table.

Literature & Lore

In 1950, Clementine Paddleford wrote in Gourmet Magazine about a life-changing, new modern convenience: already peeled chestnuts.

“Peeling a chestnut is a task women hate. It makes the arm ache; one may slice off a finger. Any way you do it, chestnut peeling is tedious. Now chestnuts come prepeeled, precooked, in 18-ounce jars, packed in the lightly salted water in which they are cooked. The chestnuts are whole—no broken specimens in our sample, at least—and perfectly peeled, not a fleck of skin left. This new product for the American cook who has no patience with tedium is the idea of B. V. Ossola, vice-president of the J. Ossola importing company of New York, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Miami… This week, Betty came calling with a satchel of samples. She asked for a can opener and a bowl and zipped out the chestnuts, 32 the jar-count, these to purée and serve as a vegetable, to use in soup or as a stuffing for turkey.” [22]Paddleford, Clementine (1898 – 1967). Food Flashes Column. Gourmet Magazine. July 1950.

“Cuando cubra las montañas de blanca nieve el enero, tenga yo lleno el brasero de bellotas y castañas…” — Luis de Góngora, Spanish poet, 1581 (“When white snow covers the mountains in January may my braiser be full of acorns and chestnuts”)

Language Notes

Romans called the nut “castanea.”

Most food writers believe that is because the tree was very abundant in Kastanaia (Κασταναία), a town in the Thessaly region of Greece.

Another possible source of the name was Kastanis, a city in Pontus (Pontus was what is now the eastern Black Sea region of Turkey.) Victor Hehn, in his 1885 “Cultivated Plants and Domesticated Animals in Their Migration from Asia to Europe”, cites the poet Nicander who wrote “Or Kastanis, a city of Pontus, where chestnuts abound…”. Hehn writes, though: “if only we could find any trace of such a city in Pontus.” [23]Hehn, Victor. Cultivated Plants and Domesticated Animals in Their Migration from Asia to Europe. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 1976. Page 295. Cooksinfo’s research has not been able to find any reference to such a town in that area, either.

Regardless, some commentators feel that with regards to either reported town, it’s just as likely that the towns could have taken their names from the abundant chestnut trees reputedly growing around them.

The French word “châtaigne” comes from castanea. Very often, when you see an “â” in French, there used to the letters “as” in the word. Think of château and castle.

In French, horse chestnuts are called “Marrons d’Inde” or “Châtaignes de cheval”.

Sources

BBC Radio 4. Food programme for Sunday, 22 December 2002 12:30 pm to 1:00 pm on chestnuts, presented by Sheila Dillon.

Whetsone, Holly. Wanted: Chestnut Growers. In: Futures Magazine. Michigan State University. AgiBioResearch. #Fall/Winter Issue. 2016. Page 34. Available online at https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/wanted_chestnut_growers (link valid as of January 2020)

Types of chestnut products

See also: Chestnut flour ; Marrons glacés.

Chestnut Purée

References

| ↑1 | Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 198. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | WebMD. Horse Chestnut. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.webmd.com/vitamins/ai/ingredientmono-1055/horse-chestnut |

| ↑3 | Lack, H. Walter. “The Discovery and Rediscovery of the Horse Chestnut”. Arnoldia Magazine. Harvard University. 2002. Volume 61, Number 4. Page 15. |

| ↑4 | Lewis, Lon D. et al. Feeding and care of the horse. Wiley-Blackwell. 1996. |

| ↑5 | Schaffer, Albert. 120 Minuten sind nicht genug. Frankfurt, Germany: Frankfurter Allgemeine. 21 May 2012. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.faz.net/aktuell/gesellschaft/biergaerten-120-minuten-sind-nicht-genug-11759037.html |

| ↑6 | Davidson, Alan. |

| ↑7 | Mason, Sarah L.R. Mason and Jon G Hather, eds. Hunter-Gatherer Archaeobotany: Perspectives from the Northern Temperate Zone. New York: Routledge. 2016. |

| ↑8 | Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 3(1):7-17 · March 2011). Available online at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225633843_Staple_or_famine_food_Ethnographic_and_archaeological_approaches_to_nut_processing_in_East_Asian_prehistory |

| ↑9 | Lizotte, Erin. What’s the difference between horse chestnuts and sweet chestnuts? Michigan State University Extension. 9 October 2019. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.canr.msu.edu/news/whats_the_difference_between_horse_chestnuts_and_sweet_chestnuts |

| ↑10 | Lizotte, Erin. |

| ↑11 | Lizotte, Erin. |

| ↑12 | Lizotte, Erin. |

| ↑13 | Chestnut Fresh Cooking Instructions. Chestnut Growers Inc.. Michigan. Accessed January 2020 at http://www.chestnutgrowersinc.com/about.shtml |

| ↑14 | Davidson, Alan. |

| ↑15 | Lizotte, Erin. |

| ↑16 | Davidson, Alan. |

| ↑17 | Virgil. Eclogues, Georgics, Aeneid. Translated by Fairclough, H R. Loeb Classical Library Volumes 63 & 64. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1916. |

| ↑18 | John Evelyn, Sylva, Chapter 7, “Of the chess-nut”, 1664. |

| ↑19 | New Larousse Gastronomique. Paris: Librarie Larousse. English edition 1977. Page 217. |

| ↑20 | Davidson, Alan. |

| ↑21 | U.S. Army Environmental Command. Flickr post. 15 July 2009. Accessed January 2020 at https://www.flickr.com/photos/armyenvironmental/4443191356 |

| ↑22 | Paddleford, Clementine (1898 – 1967). Food Flashes Column. Gourmet Magazine. July 1950. |

| ↑23 | Hehn, Victor. Cultivated Plants and Domesticated Animals in Their Migration from Asia to Europe. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. 1976. Page 295. |