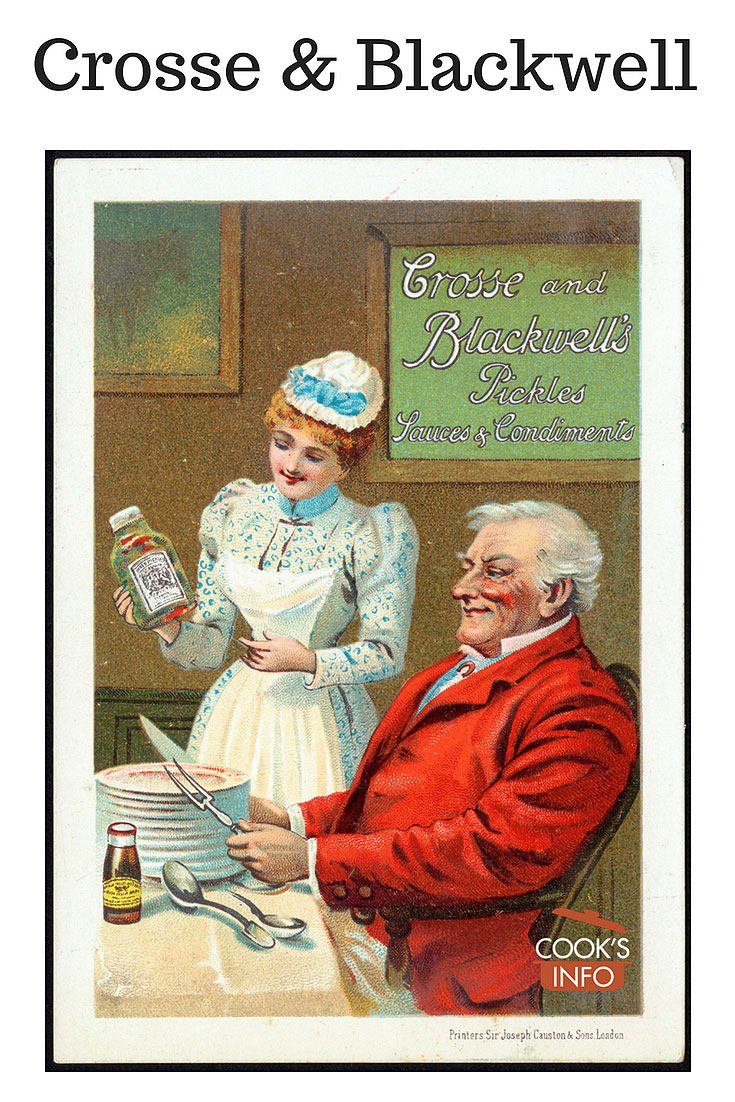

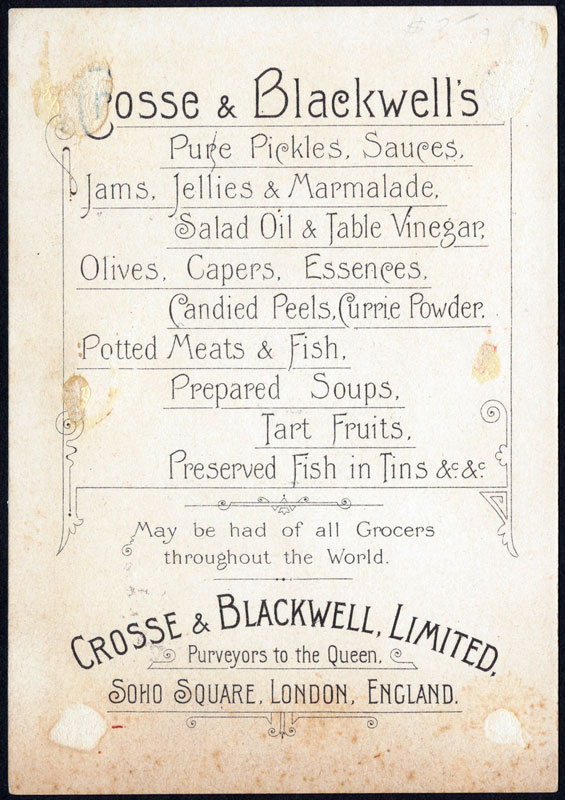

Advertising card c. 1870 – 1900. Boston Public Library, Print Department. Public Domain

Crosse & Blackwell is the brand name of a well-known British line of foodstuffs. Along with another famous 19th century food company, it was created by staff who had worked for a small grocery store in Soho, London.

West and Wyatt gives birth to Underwood and Crosse & Blackwell

In 1706, a grocery business named West and Wyatt opened on King Street in Soho, London, on the site of the old Shaftesbury Theatre. [1]Watson, Brenda. Ever So British: Pickles. Panorama: 1996. Accessed July 2018 at http://www.britannia.com/panorama/pickle.html [2]Atkins, Peter J. Vinegar and Sugar: The Early History of Factory Made Jams, Pickles and Sauces in Britain. IN: Chapter 3 in Oddy, D.J. (Ed.)(2013)

The Food Industries of Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Farnham: Ashgate ISBN 9781409454397. Chapter 3. Page 3.

The business was founded in 1706 as the West and Wyatt grocery business, which during the 1700s made and sold mainly whale and seal oil but also, condiments and pickles. [3]Atkins, Peter J. Vinegar and Sugar

West and Wyatt would, in a way, give birth to two companies well-known today. In 1817, a former employee, William Underwood, emigrated to America where he founded the Underwood line of products, including devilled ham (for more information on Underwood, see our entry on Devilled Ham.)

Two years later, in 1819, two young apprentices working at West and Wyatt became friends — Edmund Crosse (born in Chelsea, London, c. 1804) and Thomas Blackwell (born 14 March 1804.) They would remain friends their entire lives, even living and being buried near to each other.

The beginnings of Crosse & Blackwell

In 1829, they bought out West and Wyatt, renamed it to Crosse & Blackwell, and set about refreshing the product lines by purchasing new recipes from chefs. Their approach turned out to be the correct one: by 1831, they had their first Royal Appointment.

The company became a family owned and run one for the next one hundred years. (See Family Ownership below.)

In 1840, Crosse & Blackwell acquired a building at 21 Soho Square, London. Censuses seem to show that Crosse and his wife may have lived here at first until at least 1851. The firm retained this site until 1925. [4]Sheppard, F.H.W. Soho Square Area: Portland Estate: No. 21 Soho Square’, Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 72-73. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41046 Date accessed: 13 December 2008

In 1849, they opened a plant in Cork, Ireland, to produce canned salmon (in cans, as opposed to bottled, which was an innovation.)

Sometime before 1850, the company bought the canning firm of Donkin, Hall and Gamble on Blue Anchor Road in Bermondsey in South London in order to make their own tins. [5]Clow, Archibald and Nan L. The Chemical Revolution: A Contribution to Social Technology. London: Taylor & Francis. 1992. Page 577.

In 1850, Crosse & Blackwell described themselves as “Italian warehouse and oilmen and dealers in preserves, pickles and sauces” [6]Description contained in a “Deed of Covenant” dated 22 August 1850, between Crosse and Blackwell and Alexis Soyer. Two of the products they would become famous for were potted meats such as Strasbourg paste, and anchovy paste.

On 22 August 1850, Crosse & Blackwell signed a contract with the chef Alexis Soyer. Under the agreement, they would make and sell in his name a line of bottled foods such as Soyer’s Nectar, Soyer’s Relish and Soyer’s Sauce, with his face on the bottles.

In the 1861 census, Blackwell gave his occupation as an “oilman” (cooking oils presumably), employing 2002 people, and listed the headquarters as being in Soho. [7]Millard, Andrew. Bodimeade families database. Accessed 15 January 2010 at http://www.dur.ac.uk/a.r.millard/genealogy/database/individual.php?pid=I1699&ged=BODIMEADE.GED

Edmund Crosse died in 1862, and was buried in the graveyard of All Saints’ Church on Uxbridge Road in Harrow Weald, London.

National expansion

In London, the company’s administrative functions centred on Charing Cross Road. In 1875–6, the company had a large two-storey stable complex built for them at 111 Charing Cross Road by the architect R. L. Roumieu:

“…in 1875–6 Crosse and Blackwell erected new stables here to the designs of R.L. Roumieu in a severe but powerful Italian Romanesque manner. The entrance was through an archway from Crown Street, and the central covered yard was surrounded on the ground floor by accommodation for eighteen vans and four horses. A ramp led to the first floor, where there were stalls for thirty-five horses, a loose-box and living quarters for the stablemen.” [8]Sheppard, F.H.W, Editor. ‘Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road’, Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 296-312. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41110 Date accessed: 13 December 2008.

In 1877, they had a warehouse built for them by the same firm, now called Roumieu & Aitchison, at 151 to 155 Charing Cross. Owing to zoning, they weren’t able to go as tall as they wanted until 1885. They used this warehouse until 1921.

In 1879, Thomas Blackwell died shortly before Christmas on the 16th December, and was buried on the 23rd in the same place as Crosse: All Saints’ Church on Uxbridge Road in Harrow Weald, London. In fact, the two family plots are very near to each other, and can be viewed to this day (2009.)

Crosse & Blackwell advertising card c. 1870 – 1900. Boston Public Library. File 10_03_000052b / flickr / CC BY 2.0

In 1888, the company further commissioned the architects Roumieu & Aitchison for another warehouse at 157 Charing Cross Road. It was completed in 1893. In 1927, the building became a theatre, later known as the Astoria. In 2009, the government obtained the site through compulsory purchase and demolished it to build a train station. (Note: it was a warehouse, not a pickle factory, as advertising for the theatre usually said.)

From 1888 till the 1920s, they had offices at 114 – 116 Charing Cross Road. The building, still extant today, is a four storey triangular brick building (originally red brick, painted as of 2018), designed again by Roumieu & Aitchison. [9]Ibid.

Corner building Crosse & Blackwell offices at 114 – 116 Charing Cross Road, London, originally unpainted red brick. Stephen Richards / 2014/ geograph.org.uk / CC BY-SA 2.0

During the 1880s, Crosse & Blackwell had their ketchup made for them by a company called Cunnington in Deeping St James, and shipped in casks by rail to London. [10]The ketchup company sued the Great Northern Railway Company for delivering to it in 1882 someone else’s empty casks that had had turpentine in them, instead of the empty casks that Crosse & Blackwell had shipped to them to be filled. — The Law Times. Vol. XLIX, N.S. 1 December 1883. Page 392 – 394.

During this time, they grew their own onions in East Ham, Essex, storing them in sheds on what is now East Avenue there. [11]Powell, W.R. Editor. East Ham: Economic history and the marshes, A History of the County of Essex: Volume 6 (1973), pp. 14-18. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42742 Date accessed: 13 December 2008.

In the 1881 UK census, Blackwell’s son Thomas Francis Blackwell listed himself as a “Preserved Provision Manufacturer employing 654 men and boys & 552 women.” In 1889, he was President of the London Chamber of Commerce, and a founding member of the Freight Transport Association in the UK.

Former Crosse & Blackwell factory in Peterhead, Scotland. John Lord / 2013 / flickr / CC BY 2.0

International expansion

Before the First World War, Crosse & Blackwell had already established its first European plant in Hamburg.

In 1919, the company merged with James Keiller & Sons Ltd, the marmalade maker, and E. Lazenby & Son Ltd, who made preserves and sauces. Though the merged company held the name of Crosse & Blackwell, it was more of a holding or marketing company. The agreement allowed each of the three companies to carry on with complete independence.

By 1920, the company also controlled or bought out Cosmelli Packing Company Ltd, Robert Kellie & Son Ltd, Batzer & Co. and Alexander Cairns & Sons. The company had an estimated capital of over 10 million pounds. [12]Rees, J. Morgan. Trusts in British Industry 1914 – 1921. London: P.Sl King & Son Ltd. 1922. Page 193. Some people were alarmed at the growing control of Crosse & Blackwell over the food provisions market. The British Parliament was advised that “Any further extension of so large a combination as this should be carefully watched in view of its possible ultimate effect on the market.” [13]Report on Fruit. British Parliamentary Command Paper Series 878, p. 5. 1920.

In 1922, Crosse & Blackwell started making Branston Pickle.

Despite the apparent advances, and the concern about a possible effective monopoly, by 1924 the firm had suffered financial setbacks. The combined capital for all the companies under Crosse & Blackwell’s umbrella had fallen to 7.3 million pounds. They had had to write off 2.7 million pounds owing to heavy losses from poor management, duplication of effort, and internal competition between the firms. [14]Fitzgerald, Patrick and Mira Wilkins. Industrial Combination in England. Ayer Publishing. 1977. Page 193.

In 1925, Crosse & Blackwell acquired Williams & Woods Ltd (maker of candies, etc) in Ireland through their Keiller arm.

In 1927, the company constructed a large plant on the lake in Toronto to serve Canada.

Crosse & Blackwell Bldgs, Bathurst & Lakeshore Sts under construction looking northeast – Credit: Toronto Harbour Commissioners / Library and Archives Canada / PA-098619 – MIKAN 3656094 – 1927

By 1930, the holding company had plants in Baltimore, Brussels, Buenos Aires, Paris and Toronto, as well as the original one in Hamburg. [15]Chandler, Alfred Dupont & Takashi Hikino. Scale and scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Harvard University Press. 1994. Pages 369 & 372.

Crosse & Blackwell finished buildings, Bathurst & Lakeshore Streets, Toronto. Credit: Toronto Harbour Commissioners / Library and Archives Canada / PA-098370 – MIKAN 3656082 – 1931

From 1938 to 1945, the company owned a canning plant in Brighton, Ontario, Canada where they processed corn, tomatoes, new potatoes and some fruits.

By 1939, they had dedicated quality control departments at their Bermondsey canning plant in London. The chemists working there played a dual role: to ensure compliance with government quality and safety legislation, and to suggest ways of making the products more efficiently and cost-effectively without changing the product in a way that the consumer would notice. [16]French, Michael and Jim Phillips. Cheated Not Poisoned?: Food Regulation in the United Kingdom, 1875-1938. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. Page 28.

In the 1950s, Crosse & Blackwell’s advertising slogan was “Ten O’Clock Tested” to imply that everybody had their products for breakfast.

In the late 1950s, they began offering condensed soups in response to the entrance into the UK market of the American firm Campbell’s with its condensed soups (prior to that, Crosse & Blackwell’s soups were “ready-to-serve” as is out of the tin.)

The business passes through various ownerships

In 1960, Crosse & Blackwell was bought out by Nestlé. At the time of the buy out, Crosse & Blackwell had six British plants and five abroad. [17]Jones, Geoffrey. The Making of Global Enterprise. London: Routledge. 1994. Page 105.

In 1998, Nestlé closed the Crosse & Blackwell plant at Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, Scotland. It had been in operation for over 150 years, processing everything from herring to Branston Pickle.

In 2002, Nestlé sold Crosse & Blackwell to Premier Foods.

In 2003, Crosse & Blackwell launched a new, uniform branding and packaging for all products under its name, and introduced some new products.

In 2004, Crosse & Blackwell’s North American operations were bought by Smucker.

In 2005, Crosse & Blackwell were affected by a health alert concerning the red food colouring “Sudan I.” The colouring had been in a batch of chilli powder used in making their Worcestershire sauce. They had to do a world-wide recall of not only the Worcestershire sauce, but also of other products of theirs which incorporated the Worcestershire sauce as an ingredient.

As of 2008, the company made products such as Branston Pickle, Rowntree’s jelly, Sun-Pat peanut butter and Sarson’s vinegar. Crosse & Blackwell “tangy” mayonnaise remains one of the most popular brands of mayonnaise in South Africa. [18]Naidu, Edwin. Black middle class growing and spending. London: Sunday Independent. 16 March 2008, page 3.

Crosse & Blackwell claims to have the original formula for Major Grey’s Chutney.

At one point, their gravy browning was very popular.

Literature & Lore

“PICKLES, SAUCES, JAMS, &c, Free from Adulteration. THE great Medical Journal, the “London Lancet,’ on the 4th February, 1854, declared the temples of Messrs. Crosse and Blackwell were entirely free from coffer [?] ; and this statement was afterwards fully confirmed by the Analytical Chemist, Dr. Hassal, in his Work on Food and its Adulterations. CROSSE & BLACKWELL, of Soho Square, London, who have for many years enjoyed the high honor of supplying Her Majesty’s table with their Manufactures, wish to call the attention of consumers to the great superiority of their PICKLES SAUCES, JAMS, TART FRUITS, POTTED MEATS, and other Table delicacies, the whole of which are prepared with that strict attention to quality and purity, for which they have been so long celebrated. Their SAUCES are universally admitted to be the best exported ; and those who have once tasted them never return to inferior kinds. C. & B. use none but the best ingredients in their various preparations; and although purchasers may not be able to obtain them so cheaply as the goods shipped by other Manufacturers, the superiority of quality will be found to more than compensate for any increase of cost. To buy a cheap article because it is cheap, is merely to throw money away. C. & B.’s ORANGE MARMALADE cannot be equalled — it is made in SILVER PANS, entirely from the Seville Orange; their MUSHROOM CATSUP also is the very best that can be obtained from the famed Leicester Mushrooms. The above, and all other articles of CROSSE & BLACKWELL’S manufacture, may be procured of Storekeepers in Auckland and throughout the Colonies. C. & B. are Wholesale Agents for Lea & Perrin’s Worcestershire Sauce.” — Advertisement. Daily Southern Cross. Auckland, New Zealand. Volume XVII, Issue 1343, 23 October 1860, Page 4.

IT’S THE ORIGINAL CROSSE & BLACKWELL DATE and NUT BREAD

1948 promotion for Crosse & Blackwell tinned Date and Nut Bread, which appeared in the Ladies’ Home Journal.

Advertisement in “The Ladies’ Home Journal” (April 1948, page 260). Internet Archive Book Images / flickr / Public Domain [CLICK FOR FULL ADVERTISEMENT.]

Whether you have it for fancy parties or quick snacks … there’s nothing quite like this nutty, golden-brown loaf packed with choice imported dates and crunchy cashew nuts. Yes . . . Crosse & Blackwell Date & Nut Bread is always fresh … always ready to serve … for desserts … for sandwiches with your favorite spread … or just as it comes out of the handy vacuum tin. Try these delicious Date n Nut Bread recipes by C & B.

Date ‘n Nut Cream Cheese Sandwiches

Quickie festive snack in minutes. Just open a can of Crosse & Blackwell Date and Nut Bread; cut into 18 slices. Spread 9 slices with cream cheese; cover with remaining slices. Top with more cream cheese.

Easy to Make Date ‘n Nut Pudding

Boil one can of Date and Nut Bread in boiling water 30 min. Remove roll from can; slice and serve with custard sauce made as follows: Scald 1 cup milk in double boiler. Beat together 2 egg yolks, 2 tbsp. sugar, ⅛th tsp. salt; slowly add milk. Cook in double boiler til mixture coats spoon, stirring constantly. Cool slightly; add ¼ tsp. vanilla

Send for Free Recipe Book

For other delicious recipes, send for FREE copy of “25 Ways to Serve Crosse & Blackwell Date & Nut Bread” to Crosse & Blackwell Co., Dept. 75, Baltimore 24, Maryland. [19]Advertisement on page 260 of “The Ladies’ home journal”. Philadelphia: April 1948.

Family ownership of Crosse & Blackwell

Edmund Crosse married a Laura Mitchell, sometime before 1844. The couple had six children, of whom possibly three died while young. By 1855, the couple were living at Fairfields, Brookshill, Harrow Weald, Middlesex. Three of their sons were Edmund Meredith Crosse (1846 -1918) , Charles W. Crosse (1854-1905) and Sydney G. Crosse (c. 1857 – ?)

Thomas Blackwell married Jane Ann Bernasconi (1801 – 16 November 1870) on 26 August 1834. The couple lived in Harrow Weald, Middlesex. [Proctor, Ian. Restoring the legacy of Edmund Crosse and Thomas Blackwell. London: Harrow Observer. 8 May 2008. ] The Blackwells “ancestral home” had been in Harrow Weald, and Thomas’s brother Charles continued to live there in the family house at The Kiln, Clamp Hill. Members of the Blackwell family later donated land to the town such as that which is now Cedars Open Space, the Harrow Weald Recreation Ground (see photo below), and St Anselm Church. One of Blackwell’s neighbours was the composer, William Gilbert, who once complained about Blackwell’s dog. In 1868, Thomas had a house built for him on Brooksmill Drive in Harrow Weald, which remained in the family until the death of Helen Bertha Blackwell in 1955. [20]Guy Fisher Property Consultants. “Hillside.” Retrieved January 2010 from http://www.guyfisher.co.uk/property-files/HILLSIDE_sales_details_reduced.pdf

Thomas and Jane Blackwell had four children, one of whom, Thomas Francis Blackwell, died as an infant in 1835. They named the next child, a boy, born in 1838, Thomas Francis Blackwell as well. Another son died at the age of 28. Thomas Francis and his surviving brother, Samuel (1841 – 1923), went on to spend their lives with the firm. Samuel was a Director of the firm. Samuel retired from the firm in 1901, and his son, Francis Samuel Blackwell (1869 – 1951) became a Director in 1901.

Entrance to Harrow Weald Recreation Ground, Harrow, London, which was donated to the parish in 1895 by Thomas Francis Blackwell. Marathon / 2017 / geograph.org.uk / CC BY-SA 2.0

St Anselm Church, Hatch End, Harrow, built in 1895 on land donated by Thomas Francis Blackwell. John Salmon / 2002 / geograph.org.uk / CC BY-SA 2.0

Thomas Crosse’s grandson (son of Thomas Francis Blackwell), Thomas Geoffrey Blackwell (1884 – 1943) became a company director in 1905, and later a co-Chairman of Crosse & Blackwell Ltd along with Sir Frederick Eley (1866 – 1951, chair from 1932 – 1946.) In 1917, Geoffrey was awarded an OBE (Order of the British Empire) for his work in the Foreign Office at the Restriction of Enemy Supplies Department. [The Times. A New Order – Honours for War Work. August 25, 1917, p. 7 & 8]

One of Thomas Geoffrey’s sons, Charles Arthur, was killed at Dunkirk in 1940. Another, John Geoffrey Blackwell (1914-2001), worked for the firm for a time, but then switched to teaching in 1946 upon his return from prison camp after the war.

One of the Blackwell descendants and heiresses, Ursula Blackwell, married Ernö Goldfinger, later to become well-known as a British Brutalist architect.

Videos

Tomato Ketchup advertisement

Soup commercial

1983 (?) report on possible layoffs at Crosse & Blackwell’s plant at Tay Wharf in east London’s Silvertown district. The Tay Wharf site had been acquired as part of the buy-out of James Keiller & Son Ltd in 1924.

2019 South African commercial for Crosse & Blackwell mayonnaise

Sources

Chris Blackwell (1937 – ), son of Middleton Joseph Blackwell, is a record producer.

Daily Telegraph. John Blackwell (Obituary.) 23 August 2001.

French, Michael and Jim Phillips. Cheated Not Poisoned?: Food Regulation in the United Kingdom, 1875-1938. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

Invaluable Auction Database. Lot 37 : Joseph Knibb London. Accessed 15 December 2008 at http://www.invaluable.com/auction-lot/joseph-knibb-london-1-c-vv78x8folb

Proctor, Ian. Restoring the legacy of Edmund Crosse and Thomas Blackwell. London: Harrow Observer. 8 May 2008.

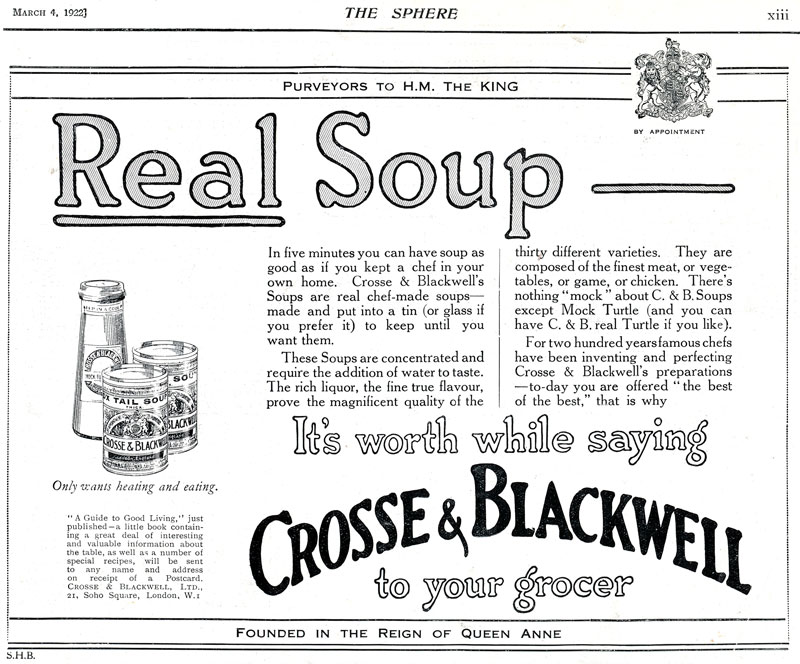

Crosse & Blackwell soup advertisement. From The Sphere magazine, Royal Marriage edition, 1922. Pamla J. Eisenberg / flickr / CC BY-SA 2.0

References

| ↑1 | Watson, Brenda. Ever So British: Pickles. Panorama: 1996. Accessed July 2018 at http://www.britannia.com/panorama/pickle.html |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Atkins, Peter J. Vinegar and Sugar: The Early History of Factory Made Jams, Pickles and Sauces in Britain. IN: Chapter 3 in Oddy, D.J. (Ed.)(2013) The Food Industries of Europe in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Farnham: Ashgate ISBN 9781409454397. Chapter 3. Page 3. |

| ↑3 | Atkins, Peter J. Vinegar and Sugar |

| ↑4 | Sheppard, F.H.W. Soho Square Area: Portland Estate: No. 21 Soho Square’, Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 72-73. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41046 Date accessed: 13 December 2008 |

| ↑5 | Clow, Archibald and Nan L. The Chemical Revolution: A Contribution to Social Technology. London: Taylor & Francis. 1992. Page 577. |

| ↑6 | Description contained in a “Deed of Covenant” dated 22 August 1850, between Crosse and Blackwell and Alexis Soyer. |

| ↑7 | Millard, Andrew. Bodimeade families database. Accessed 15 January 2010 at http://www.dur.ac.uk/a.r.millard/genealogy/database/individual.php?pid=I1699&ged=BODIMEADE.GED |

| ↑8 | Sheppard, F.H.W, Editor. ‘Shaftesbury Avenue and Charing Cross Road’, Survey of London: volumes 33 and 34: St Anne Soho (1966), pp. 296-312. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=41110 Date accessed: 13 December 2008. |

| ↑9 | Ibid. |

| ↑10 | The ketchup company sued the Great Northern Railway Company for delivering to it in 1882 someone else’s empty casks that had had turpentine in them, instead of the empty casks that Crosse & Blackwell had shipped to them to be filled. — The Law Times. Vol. XLIX, N.S. 1 December 1883. Page 392 – 394. |

| ↑11 | Powell, W.R. Editor. East Ham: Economic history and the marshes, A History of the County of Essex: Volume 6 (1973), pp. 14-18. URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=42742 Date accessed: 13 December 2008. |

| ↑12 | Rees, J. Morgan. Trusts in British Industry 1914 – 1921. London: P.Sl King & Son Ltd. 1922. Page 193. |

| ↑13 | Report on Fruit. British Parliamentary Command Paper Series 878, p. 5. 1920. |

| ↑14 | Fitzgerald, Patrick and Mira Wilkins. Industrial Combination in England. Ayer Publishing. 1977. Page 193. |

| ↑15 | Chandler, Alfred Dupont & Takashi Hikino. Scale and scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Harvard University Press. 1994. Pages 369 & 372. |

| ↑16 | French, Michael and Jim Phillips. Cheated Not Poisoned?: Food Regulation in the United Kingdom, 1875-1938. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000. Page 28. |

| ↑17 | Jones, Geoffrey. The Making of Global Enterprise. London: Routledge. 1994. Page 105. |

| ↑18 | Naidu, Edwin. Black middle class growing and spending. London: Sunday Independent. 16 March 2008, page 3. |

| ↑19 | Advertisement on page 260 of “The Ladies’ home journal”. Philadelphia: April 1948. |

| ↑20 | Guy Fisher Property Consultants. “Hillside.” Retrieved January 2010 from http://www.guyfisher.co.uk/property-files/HILLSIDE_sales_details_reduced.pdf |