Alexis Benoit Soyer. (Source: The Modern Housewife of Menagere. Published 1850.)

Alexis Benoit Soyer was a famous chef and food author in Victorian England. He was a household name, and even often the subject of fun, if only owing to his penchant for flamboyant clothing that included a red velvet beret.

Early Years

Alexis Benoit (aka Bénoist) Soyer was born 4 February 1810 in France rue Cornillon in Meaux-en-Brie on the Marne river east of Paris (some erroneously the birth year was 1809.) His father, Emery Roch Alexis Soyer, was a former grocer. His mother’s name was Marie Madeleine Francoise Chamberlan. He was the youngest of five sons, two of whom had died in their infancy. Philippe, the eldest, had been born in 1799. His other surviving brother, Louis, born 1801, later became a cabinet maker.

In 1799, eleven years before Alexis was born, Emery had had his own grocery store in Meaux-en-Brie on rue du Tan south of the Cathedral. In 1804, however, the business went bust, and the family had to move to the poorest part of town on rue Cornillon, where Alexis would be born six years later. By the time Alexis came along, his parents no longer had the grocery business, so his father had taken on other jobs, even working as a labourer building a canal.

Alexis’s mother had wanted him to enter the Church. She enrolled him in the choir and choir school at the nearest Cathedral in 1819 when he was nine years old; reputedly, at that age, he had a good voice. In 1821, however, after his twelfth birthday, he was expelled from the school for ringing the Cathedral bells one night as a prank, causing the soldiers to turn out. Historians, however, aren’t sure how much of any of this story is true, from his attending choir school right down to his mother Marie wanting him to be a priest in the first place, as they haven’t been able to find any backing for it: the story is what Soyer had told his secretaries, so that’s what they wrote down when they wrote his posthumous memoirs on his behalf.

Entry into restaurant career

In any event, in 1821 Alexis started a five-year restaurant apprenticeship in a restaurant owned by a George Rignon in Thiverval-Grignon, a town near Versailles. His brother Philippe who worked there arranged the apprenticeship for him. He remained there until his apprenticeship was up in 1826.

His first job after his apprenticeship was at a restaurant owned by a man named D’Ouix in Paris on the Boulevard des Italiens, the same street where the famous Café Le Cardinal and Café Anglais were. He worked for D’Ouix for three years until 1830. He was quickly promoted to second cook, then to head chef over 12 others in the kitchen.

By June 1830, at the age of 20, Alexis had changed jobs, and become assistant to the head chef for Jules Armand, the Prince de Polignac, who had been the French ambassador to England from 1823 to 1829. This position, however, was to be short-lived for Alexis, as he was side-swiped by the continuing tumult of French history.

The French Monarchy had been restored after Napoleon, with first Louis XVIII, then Charles X reigning as monarchs with limited power. In August 1829, Charles had appointed the Prince de Polignac to be head of the French Foreign Office as well as Prime Minister and on 25 July, a month after Alexis had started working for the prince, the prince and Charles X dissolved the elected legislature, ended freedom of the press, changed how elections would be held and called a new election.

Protests and uprisings began the very next day. Parisians took to their favourite sport of hauling cobblestones out of the streets, and using them to build barricades with when the stones weren’t needed for heaving at authorities. That very same day, 26 July, Alexis’ kitchen was assigned the task of creating a grand banquet for the Prince de Polignac to celebrate Charles X’s new decrees. While Alexis and his staff were working, a enraged mob burst into the kitchen and shot two of his coworkers. Alexis saved his own life by bursting out into a spirited rendition of the Marseillaise. The mob loved him, and carried him on their shoulders out into the street (at least, that’s how Alexis told the story later.) Finally on 2 August, Polignac was arrested, Charles X resigned and his brother Louis-Philippe came to the throne and promptly rescinded all the decrees. Still, Alexis felt it better to leave France, owing to any lingering associations with the now-hated regime.

Soyer moves to England

In the last half of the year 1830, Alexis arrived as a 20 year old in England. By 1831, he had a job in London. His brother Philippe was already there, working as a chef for Adolphus Guelph, Duke of Cambridge (George III’s youngest son.) Philippe got him a job helping him cook for the Duke.

Alexis then worked for a string of other notables such as the Duke of Sutherland, the Marquis of Waterford, the Marquis of Ailsa (at Isleworth), and William Lloyd of Aston Hall (Oswestry.)

In 1837, Alexis married Elizabeth Emma Jones, who as an established artist, had exhibited at Royal Academy when she was 10. She helped him in his work by acting as his secretary.

Reform Club work

And, also in 1837, Alexis secured the position that was to assure him fame, as chef of the Reform Club (formed 1836 in London.) Though meeting temporarily at a house at 104 Pall Mall, by the time Alexis was engaged, the club was having new headquarters at 104 to 105 Pall Mall built (the story of how the temporary premises were demolished to make room for the new site is quite convoluted: in any event, the new building spanning both lots was officially opened on 1 March 1841.) Getting in on the ground floor while designs were still being agreed allowed Alexis to specify how he wanted the kitchens designed. His design of the kitchen alone ended up gaining him fame: chefs from various parts of Europe asked for tours of it. He introduced gas as a cooking fuel, and adjustable oven temperatures to the kitchens.

On 28 June 1838, Alexis cooked breakfast for 2,000 people at the club for Queen Victoria’s coronation.

In 1839 or 1840, his brother Philippe died of consumption.

In 1842, his wife Elizabeth died from complications from pregnancy. On the night of the 29th of August, and well into the early morning of the next day, there was a thunderstorm which people afterward said frightened Elizabeth into going into early labour. Both she and the baby died. One wag proposed that her tombstone should read “soyez tranquille” (a take on Alexis’s last name.)

Sometime after Elizabeth’s death, Alexis fell in love Fanny Cerito, a ballerina. Fanny had been married, but the marriage failed. Her father disapproved of any relationship with Alexis. Consequently, they kept their love, and affair, secret until Alexis died.

Alexis did, however, have a son — though not by Elizabeth or Fanny. The son’s name was Jean Alexis Lamain, born in 1830 in Paris at 22 Quai de L’École. The mother’s name was Adele Lamain, and Alexis did apparently have relations with her while still in Paris before he left for England. Jean Alexis presented himself in England in 1853 to Alexis. Alexis accepted without question that Lamain was his son, and Lamain changed his last name to Soyer.

Jean Alexis (Lamain) Soyer went on to have a son, Nicholas Soyer (1864 — 1935) who became a well-known chef in England as well. In a way, Nicholas invented cooking in paper bags — though not brown paper bags, but rather greaseproof paper folded into pouches. His book, published 1911, urged the reader to buy such paper bags with his die-stamped signature on them.

After Elizabeth’s death, Alexis engaged in charitable activities in her memory. Sometime between 1842 and 1846, he opened an art gallery called “Soyer’s Philanthropic Gallery” at which he exhibited Elizabeth’s work. He used some of the money the gallery earned to fund soup kitchens in London.

In 1846, he published the “The Gastronomic Regenerator (1846)” his first book, which took him 10 months to write amidst all his other work. In it, he wrote proudly of the table he had had designed for the centre of the kitchen for the Reform Club: “In the middle is an elm table, made on a plan entirely original, having twelve irregular sides, and giving the utmost facility for the various works of the kitchen, without any one interfering with another.”

By the end of 1846, Alexis was increasingly concerned about the potato famine in Ireland, and by February 1847 was writing letters to the newspapers about it. He was consequently appointed by British government under Prime Minister Russell to go to Ireland, and invited as well from the other end by the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Lord Bessborough, to come help. [See Literature & Lore section at end.]

Alexis took a leave of absence from his work at the Reform Club, and arriving in Dublin, had a building purpose-built outside the royal barracks to serve as a soup kitchen, selling food at half-price. He had aimed to feed a maximum of 5,000 people a day, but ended up feeding 8,750 at its busiest instead.

While in Ireland, he published his book called “Charitable Cookery”, which sold for sixpence a copy. The book wasn’t for the poor — they couldn’t read, but rather to raise money for charities helping the poor. He raised £50 for the first edition of 10,000 copies, which sold out in a flash. Within four months,, 110,000 copies had been printed and sold; by 1867, over 250,000 copies had been sold.

When everything was up and running smoothly to his satisfaction, he handed the operations over to people in Dublin and returned to his work in London. By 1849, he was back in London.

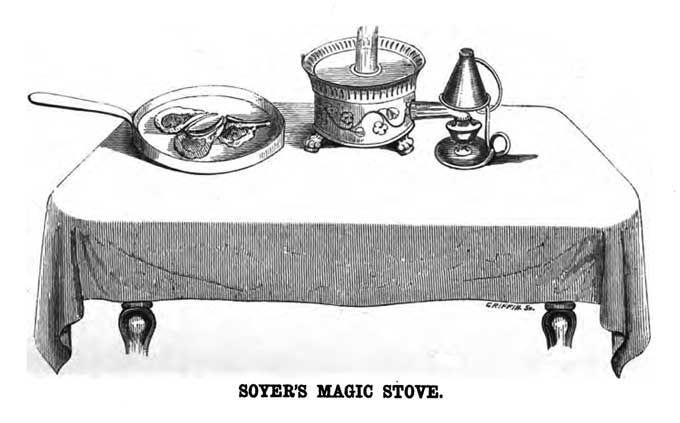

Alexis turned his attention to improving kitchen appliances, and invented various stoves including a camping stove called “Soyer Field Stove” (which enabled cooking no matter what the weather was) and one he called the “Magic Stove.”

Soyer’s Magic Stove (Source: The Modern Housewife of Menagere. Published 1850.)

Meanwhile, though, trouble was brewing at the Reform Club. During his tenure there, he had threatened a few times to resign over various things. In May 1850, he tendered his resignation once again, despite being paid nearly £1,000 a year. Alexis was upset that the Reform Club had decided to allow non-members into the coffee room. But Alexis had played the resignation game once too often: this time, Lord Marcus Hill accepted it, perhaps having decided that things hadn’t suffered too badly during Alexis’s absence in Dublin. He was succeeded at the Reform Club by chef Charles Elmé Francatelli.

Soyer the entrepreneur

With the Reform Club now a closed chapter in his life, Alexis decided to become an entrepreneur and cash in on his name. He signed a contract with Crosse & Blackwell on 22 August 1850, which would make and sell in his name a line of bottled foods such as Soyer’s Nectar, Soyer’s Relish and Soyer’s Sauce, with his picture on the bottles.

In May 1851, Alexis opened his own restaurant in Kensington in a building called “Gore House” (referred to by some as “Gore Lodge”,) which stood where Albert Hall now is on the south side of Hyde Park. He called the restaurant the “Gastronomic Symposium of All Nations” or “Soyer’s Universal Symposium to all Nations.” He was counting on customers crossing the street from Hyde Park, where the Great Exhibition of 1851 was being held. Each room of the restaurant had a flamboyant theme which echoed the various themes of the exhibition. Alexis created menus of varying prices so that not just the wealthy could dine there. But however many people came, it wasn’t enough to make up for all the money Alexis had spent on getting the restaurant the way he wanted it. The restaurant had to close for lack of money after just three months; Alexis lost £7,000 on the venture.

Through the rest of 1851 and on to 1855 Alexis promoted his books, his bottled goods and his stoves, and consulted as a banquet and feast organizer. He made it a condition that banquets he organized should send any leftover food to the poor.

Alexis Benoit Soyer, c. 1853. Frontispiece from ‘Soyer’s Culinary Campaign’

Soyer and feeding the troops

By 1855, Alexis was worried by reports he was reading in the Times about the health and nutrition of British soldiers in the Crimean War: they were dying of food poisoning and malnutrition before they even got to a battlefield. He wrote a letter to the Times on 2 February 1855 offering to go to the Crimea to help at his own expense to advise the army cooks. His letter was published in the Times the very next day, on 3rd February 1855.

THE HOSPITAL KITCHENS AT SCUTARI

To the Editor of the Times

SIR,- After carefully perusing the letter of your correspondent, dated Scutari, in your impression of Wednesday last, I perceive that, although the kitchen under the superintendence of Miss Nightingale affords so much relief, the system of management at the large one in the Barrack Hospital is far from being perfect. I propose offering my services gratuitously, and proceeding direct to Scutari, at my own personal expense, to regulate that important department, if the Government will honour me with their confidence, and grant me the full power of acting according to my knowledge and experience in such matters.I have the honour to remain, Sir,

Your obedient servant

A SoyerFeb. 2, 1855.

The Duchess of Sutherland, who knew of Alexis and who had read his letter, helped him gain the permission of Lord Panmure to have the authority both to go and to make any changes that he saw fit. One of his secretaries who would later assist in the posthumous publication of Alexis’s memoirs was a man named James Lomax. Lomax declined to make the Crimea trip, and Alexis engaged a Thomas Garfield to go in his stead.

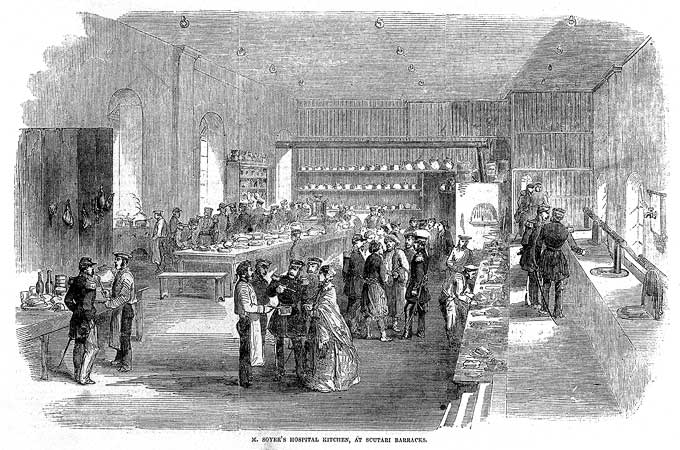

Prior to Alexis’s arrival in the Crimea, men would be given their rations and be responsible for storing them and cooking them themselves. Soyer reorganized the distribution of rations: he had a cook appointed for each regiment, who would be responsible for collecting and cooking the rations for everyone in that regiment. He also revised the diets at two hospitals, one at Scutari and one at Constantinople, and worked with Florence Nightingale in planning the diets for hospitals at Balaklava. He also rolled up his sleeves and did some cooking himself for the army’s fourth division. While in the Crimea, however, Alexis got fever himself, from which he never fully recovered.

Soyer’s kitchens at Scutari Barracks. Wood engraving, Wellcome Library no. 22790i.

Alexis returned to London from the Crimea trip on 3 May 1857. He continued his interest in modernizing army food, supervising the construction of a model kitchen at Wellington Barracks in London and giving a lecture at the United Service Institution on 18 March 1858.

Final days

Alexis died 5 August 1858 at St. John’s Wood, London, at the age of 48 (or 49 if the 1809 birth date is correct.) On 11 August, he was buried beside Elizabeth at Kensal Green Cemetery. Shortly afterwards, all his possessions were seized by a creditor named David Hart, who destroyed all his papers and notes.

Alexis and Elizabeth were buried in the Protestant part of Kensal Green Cemetery. Some speculate that Alexis’s family may in fact have been closet Protestants, though that was almost impossible in France after the recall of Edict of Nantes in 1685 (there were indeed Protestant Soyers at that time who left France, went to Switzerland and who then later migrated to British North America, particularly New Brunswick.) As possible backing for this, they point out that in fact Alexis’s first professional charitable act was trying to help weavers in Spitalfields, London, many of whom were descendants of Huguenots (French Protestants.) It may also have been, however, that Alexis’s wife was Protestant, and that he was indifferent to which religion he was buried in. He was, after all, also a devoted Mason. One of his Masonic titles was “Sovereign Prince Rose Croix of Heredom”, which stage he had reached by October 1853.

Though Alexis could sign his name, some suspect that he never actually learned to write, in French or English. He always had either a secretary who was bilingual French and English, or an English one and a French one. Those who believe that he couldn’t write point to two things: that after his wife died, he employed a tutor for a few months to teach him handwriting, and that he never actually physically wrote down any words himself. This last point, however, it’s difficult to be quite so sure of, given that his papers and notes were destroyed.

The Memoirs of Alexis Soyer were written and published in 1859 by people who had been his secretaries: James Lomax (mentioned earlier), J.R. Warren and Francis Volant, even though by the time of his death, Volant no longer worked for Soyer and in fact the two of them had fallen out. It’s in this memoir that his birth date is given as 1809 by them. In fact, though, Alexis’s birth certificate shows 1810.

Books

- 1846. The Gastronomic Regenerator

- 1847. Soyer’s Charitable Cookery

- 1850. The Modern Housewife of Menagere

- 1853. The Pantropheon; or, History of Food [1]The Pantropheon is credited to Alexis, but it was in fact mostly written by a M. Adolphe Duhart-Fauvet. Soyer allowed his name to be used as the author, though he wrote only the last chapter.

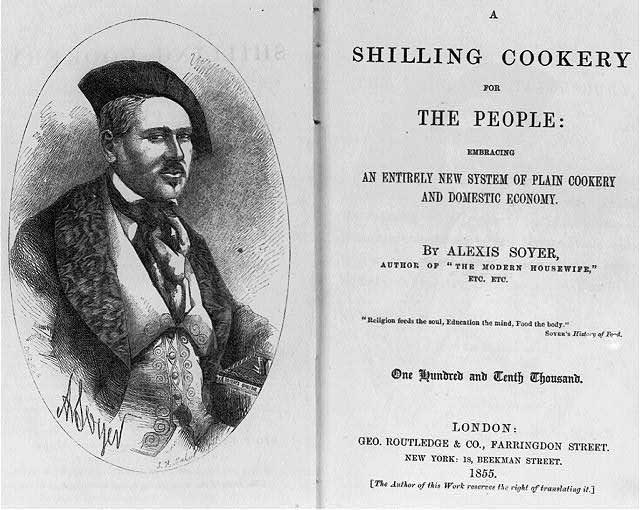

- 1854/55. A Shilling Cookery Book for the People

- 1857. Soyer’s Culinary Campaign

- 1860. Instructions for Military Hospitals (published posthumously)

Alexis Soyer: A Shilling Cookery for the People. London 1855. Title page.

Literature & Lore

M. SOYER AND THE SOUP ESTABLISHMENTS FOR IRELAND.

We learn that the Government have resolved forthwith to despatch M. Soyer, the chef de cuisine of the Reform Club, to Ireland, with ample instructions to provide his soups for the starving millions of Irish people. Pursuant to this wise and considerate resolve, artificers are at present busied day and night, constructing the necessary kitchens, apparatus, &c, with which M. Soyer starts for Dublin direct to the Lord Lieutenant. His plans have been examined both by the authorities at the Board of Works and the Admiralty, and have, after mature consideration, been deemed quite capable of answering the object sought.

The soup has been served to several of the best judges of the noble art of gastronomy at the Reform Club, not as soup for the poor, but as a soup furnished for the day in the carte. The members who partook of it declared it excellent. Among these may be mentioned Lord Titchfield and Mr. O’Connell. M. Soyer can supply the whole poor of Ireland, at one meal for each person, once a day. He has informed the executive that a bellyfull of his soup, once a day, together with a biscuit, will be more than sufficient to sustain the strength of a strong and healthy man.

The food is to be “consumed on the premises.” Those who are to partake enter at one avenue, and having been served they retire at another, so that there will be neither stoppage nor confusion. To the infant, the sick, the aged, as well as to distant districts, the food is to be conveyed in cars furnished with portable apparatus for keeping the soup perfectly hot. It would be premature to enter into further details. M. Soyer has satisfied the Government that he can furnish enough and to spare of most nourishing food for the poor of these realms, and it is confidently anticipated that there will soon be no more deaths from starvation in Ireland.” — The Cork Examiner. 26 February 1847.

One wag felt that Soyer was more likely to be remembered for his skill at organizing soup kitchens, than he was for any soup he himself actually made:

“Soyer is another artist and writer on gastronomic subjects, whose name has been a good deal before the public. He is a very clever man, of inventive genius and inexhaustible resource; but his execution is hardly on a par with his conception, and he is more likely to earn his immortality by his soup-kitchen than by his soup.” [2]Hayward, Abraham. The Art of Dining; or, Gastronomy and Gastronomers. In: The Epicure. Issue 53, Vol. V. April 1898. Page 184.

In “Lady Chesterfield’s Letters to Her Daughter”, Lady Constance Chesterfield cites Soyer as an example of a celebrity cook who, she felt, couldn’t actually cook:

“The cook henceforth was to be no more an honest hardworking upper servant in a white jacket and nightcap, mixing his sauces here, and giving an eye to his stewpans there, but an “artist,” on whom it would be expedient, at the first convenient opportunity, to bestow the ribbon of the Legion of Honour — although far worse men than cooks have enjoyed that decoration ere now, my dear — and who, away from his kitchen, was to belong to a club of cognoscenti, deliver opinions on the paintings in the Royal Academy Exhibition, drive a cabriolet with a tiger, and deliver lectures at literary and scientific institutions.

These absurdities culminated in the person of the late M. Soyer, whom several of my military friends remember to have seen in the Crimea; who, according to what I have heard of him, was one of the best-natured, honestest, most generous souls that ever existed, with just enough of the Gascon in his composition to make his vanity and braggadocio amusing; who had a real faculty for invention and organisation; who would have made an excellent commissary, hotel-keeper, comedian, or dancing-master; who was the prince of good fellows, the merriest of diners-out, the staunchest and tenderest of friends; who might have been, and was, anything but a COOK. It wasn’t in him. He couldn’t “skim off the fat,” “chop the liver,” or “serve hot.” He called his dishes by fine names. They cost a great deal of money, and didn’t taste well when eaten.” — — Sala, George Augustus. Lady Chesterfield’s Letters to Her Daughter. London: Houlston and Wright. 1860. Page 91.

Alexis Soyer House. 28 Marlborough Place, St John’s Wood, NW8, London. (© Simon Harriyott (2012) / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY 2.0)

Videos

Pen Vogler, Co-Curator of the Charles Dickens Museum, discusses Soyer in this 2019 video.

Sources

Brandon, Ruth. The People’s Chef: Alexis Soyer, A Life in Seven Courses. London: Wiley. 2005.

Reid, Aileen. Saved lives and tickling taste buds. London: Daily Telegraph. 12 July 2006.

Soyer, Nicolas. Soyer’s Standard Cookery : A Complete Guide to the Art of Cooking Dainty, Varied, and Economical Dishes for the Household. London: Andrew Melrose. 1912.

References

| ↑1 | The Pantropheon is credited to Alexis, but it was in fact mostly written by a M. Adolphe Duhart-Fauvet. Soyer allowed his name to be used as the author, though he wrote only the last chapter. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Hayward, Abraham. The Art of Dining; or, Gastronomy and Gastronomers. In: The Epicure. Issue 53, Vol. V. April 1898. Page 184. |