Old public water fountain. Tom / Pixabay.com / 2020 / CC0 1.0

The 13th of October was the Roman holiday of Fontinalia.

The day celebrated the minor Roman god “Fontus” aka “Fons”, who was a god of water springs, and more broadly, the day celebrated the gift of water.

Fontus was the son of Juturna, also a water god, who also has her own festival day on the 11th of January called the Juturnalia.

People celebrated Fontinalia by placing flowers and garlands around springs, wells and public fountains. Some scholars speculate that some people may have tossed coins or votive items into the water sources as well as other offerings. They also speculate that the holiday signalled a time to repair and maintain these water sources in advance of the day.

In many cultures, sources of water were highly regarded, and revered. There were many wells regarded as holy in England and Ireland; these were often left “wild”. The Romans, however, being compulsive civic organizers, mastered their water sources both in Rome and elsewhere, and made them into shared community resources.

#Fontinalia

See also: Water, Juturnalia, Roman Food, Roman Holidays

Activities for today

- Visit a public water fountain and toss a coin in (if it is allowed there);

- think about your use of water and how to use it more wisely — could water used to wash produce be captured and go on the garden?;

- considering supporting an organization working to bring safe water to people around the world.

History

The Roman writer Marcus Terentius Varro mentions Fontinalia:

“Fontanalia from Fons, which is the day of his holiday; owing to him then they throw crowns into the fountains, and crown the wells.” — Marcus Terentius Varro. De Lingua Latina. Liber IV. III. (Varro. On the Latin Language, Volume I: Books 5-7. Translated by Roland G. Kent. Loeb Classical Library 333. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1938. Page 195.)

The Roman poet Horace wrote a poem which some interpret as referring to this holiday. It mentions offerings of wine being poured, the sacrifice of a kid goat, and wreaths of flowers being tossed as offerings into springs, streams, and rivers. (See Literature & Lore below).

Though Fontus was a minor god in the Roman pantheon, he was an old one, and had his name attached to several things.

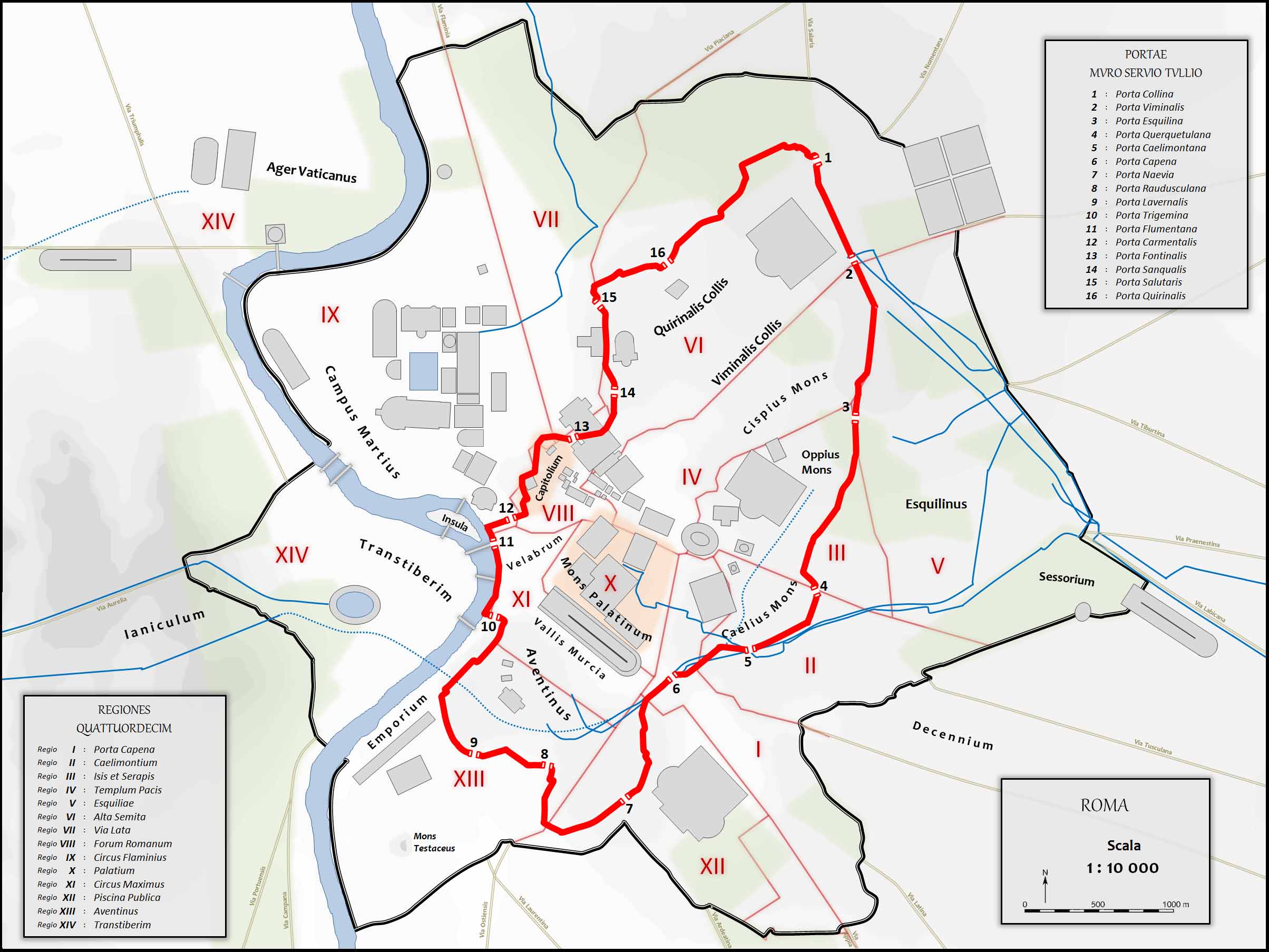

There was an altar to Fontus on the Janiculan Hill west of the Tiber, and a gate — the Porta Fontinalis — named after him which led to the Campus Martius at the north-west of the city.

#13 on map shows location of Porta Fontinalis. Cassius Ahenobarbus / wikimedia / 2013 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Presumed remains of the Fontinalis Gate. Galzu / wikimedia / 2010 / Public Domain

Cicero mentions a shrine called the “delubrum Fontis”, which was possibly located just outside the Porta Fontinalis gate. [1]Cicero. De Natura Deorum / On the Nature of the Gods. Academics. Translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 268. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933. Page 336. https://www.loebclassics.com/view/marcus_tullius_cicero-de_natura_deorum/1933/pb_LCL268.337.xml

Altar dedicated to Fontus. Luca Giarelli / wikimedia / 2009 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Pliny the Younger mentions a spring in Umbria, Italy, into which people tossed offerings of coins and pebbles. The spring, still extant, is the source of the Clitumnus (Clitumno today) river. There were temples by the spring.

Church built using parts of temples at the spring of Clitumnus. Georges Jansoone / wikimedia / 2008 / CC BY 3.0

“Have you ever seen the spring at Clitumnus? If not — and I think you have not, or else you would have told me about it — go and see it, as I have done quite recently. I only regret that I did not visit it before. A fair-sized hill rises from the plain, well wooded, and dark with ancient cypress trees. From beneath it the spring issues and forces its way out through a number of channels, though these are of unequal size. After passing through the little whirlpool which it makes, it spreads out into a broad sheet of pure and crystal water, so clear that you can count the small coins and pebbles that have been thrown into it.” (Pliny, Ep. 8.8)

The spring at Clitumnus. Aracuano / wikimedia / 2008 / CC BY-SA 3.0

People who toss coins into the fountains in Rome may be participating in a tradition far, far older than they know.

Literature & Lore

Horace’s poem in honour of a spring of water:

O Fons Bandusiae

Horace, Odes 3.13

“Spring of Bandusia, brighter than crystal,

deserving of sweet wine, and no less of flowers,

tomorrow You shall have the gift of a kid,

for which its brow, swelling with horns

just budding, predicts battle and the pleasures of love,

but vainly; for he will dye Your

cool edges with his red blood,

this offspring of a playful flock.

You the fierce hour of the blazing summer heat

Has no way to touch;

delightful coolness You

offer to pour out for tired oxen and the wandering flock.

You too shall be one of the noble springs

as I tell (in my verse) of the oak tree set above

the hollow rocks from where, chattering,

Your waters leap down

O fons Bandusiae, splendidior vitro,

dulci digne mero non sine floribus,

cras donaberis haedo,

cui frons turgida cornibus

primis et venerem et proelia destinat

frustra: nam gelidos inficiet tibi

rubro sanguine rivos

lascivi suboles gregis.

te flagrantis atrox hora Caniculae

nescit tangere, tu frigus amabile

fessis vomere tauris

praebes et pecori vago.

fies nobilium tu quoque fontium

me dicente cavis impositam ilicem

saxis, unde loquaces

lymphae desiliunt tuae

Resources

Falda, Giovanni Battista. Romanorvm Fontinalia. (Roman fountains. In Latin).

Sources

Grillo, Stella. Fontinalia, la festa delle acque sorgive dedicate al Dio Fons. Rome, Italy: Metropolitan Magazine. 14 October 2021. Accessed October 2021 at https://metropolitanmagazine.it/fontinalia-la-festa-delle-acque-sorgive-dedicate-al-dio-fons/

Ignacio Ramos Gay, “Naumachias, the Ancient World and Liquid Theatrical Bodies on the Early 19th Century English Stage”, Miranda [Online], 11 | 2015, Online since 21 July 2015, connection on 23 November 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/6745; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.6745

Michels, Agnes K. “Roman Festivals: October—December.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 68, no. 1, American Classical League, 1990, pp. 10–12, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43919166.

Phillips, C. Robert. “Fontinalia.” Oxford Classical Dictionary. 22. Oxford University Press. Date of access 23 Nov. 2021, <https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-2698>

Struck, Peter T. Online dictionary of Greek and Roman Mythology. University of Pennsylvania. Accessed October 2021 at https://www2.classics.upenn.edu/myth/php/tools/dictionary.php?method=did®exp=1068

References

| ↑1 | Cicero. De Natura Deorum / On the Nature of the Gods. Academics. Translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 268. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1933. Page 336. https://www.loebclassics.com/view/marcus_tullius_cicero-de_natura_deorum/1933/pb_LCL268.337.xml |

|---|