Iodized salt. Kiliweb / Open Food Facts / CC BY-SA 3.0

Iodine is a vital trace element that humans need to acquire continually through their diet.

Fortification of table salt with iodine (aka salt iodination) in many countries has become an important tool for delivering a public health to ensure that iodine deficiency is prevented.

Over the course of your life you only need 1 teaspoon of iodine, but without it, your body goes to hell in a handbasket. And you can’t just take 1 teaspoon and be done with it: you need a few hundredths of a gram periodically.

Seaweed is a very rich source of iodine; seafood can be good as well.

The European Food Information Council says:

“Some of the richest sources of iodine are seafood, such as fish, shellfish, molluscs and seaweed.” [1]EUFIC. Iodine: foods, functions, how much do you need & more. 11 January 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.eufic.org/en/vitamins-and-minerals/article/iodine-foods-functions-how-much-do-you-need-and-more

The Iodine Global Network cautions, however, not to rely on these sources for iodine unless they are a daily part of your diet:

“Salt water fish and seafood have high natural iodine content, but their contribution to the overall dietary iodine intake is modest unless consumed every day.” [2]Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm

Another way that consumers get iodine is through dairy and meat because iodine is added to animal feed.

“The iodine content of plant foods depends on the iodine levels in soil and in groundwater used in irrigation, in crop fertilizers, and in livestock feed.” [3]Leung, Angela M et al. “History of U.S. iodine fortification and supplementation.” Nutrients vol. 4,11 1740-6. 13 Nov. 2012, doi:10.3390/nu4111740

See also: Salt

- 1 The population health need for iodine intake

- 2 Iodine distributed unevenly on the planet

- 3 How is salt fortified with iodine?

- 4 Why was salt chosen to be fortified with iodine?

- 5 Why is iodized table salt still white?

- 6 Salt reduction versus salt as an iodine delivery vehicle

- 7 Loss of iodine from iodized salt

- 8 Salt iodization in various countries

- 9 Salt iodization in Switzerland

- 10 History of salt iodination

- 11 Language notes

- 12 Further reading

The population health need for iodine intake

Our bodies need iodine in only very low amounts:

“The dietary reference value (DRV) for healthy adults (over the age of 18) is 150 μg of iodine per day. During pregnancy and lactation, needs can go up to 200 μg per day.” [4](Note: these are estimates from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Consult your physician and local health authorities.) EUFIC. Iodine: foods, functions, how much do you need & more. 11 January 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.eufic.org/en/vitamins-and-minerals/article/iodine-foods-functions-how-much-do-you-need-and-more

Owing to the low requirements, it is often called a ‘trace mineral’ meaning that it is only needed in trace amounts. Note though that despite it being required in only low amounts, low does not mean “optional”. It’s not: it’s vital for our bodies. The thyroid gland in our bodies requires iodine to produce two important hormones:

“Iodine is found in two hormones made by the thyroid gland: thyroxine (also called T4 because it has 4 iodine atoms) and the more active triiodothyronine (T3 which has 3 iodine atoms). T3 has broad ranging effects on growth and development (including of the foetus during pregnancy), metabolism including temperature and blood glucose control, and heart and brain function. It is also involved in physical and emotional responses to stress.” [5]What happens when micronutrient needs aren’t met?. In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Online course. Step 3.9. Accessed August 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1159992

Iodine deficiency leads to problems such as goiter, when the thyroid gland enlarges into a fleshy bulge on the neck.

“In all age groups, a lack of iodine causes the thyroid to expand, producing a goitre (a swelling in the neck) that is a visible sign of iodine deficiency.” [6]Gong, Yun Yun. The challenges of balancing global food safety and nutritional need In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Step 1.12. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1163778

Other health problems occur as well.

“Iodine deficiency is among the four major nutritional deficiencies in the world and can lead to several medical disorders, including goitre (swelling of the thyroid gland), stunted physical and intellectual development, stillbirths, and spontaneous abortions.” [7]Iodine status of Canadians, 2009 to 2011. Statistics Canada. 29 November 2012. Accessed November 2022 at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2012001/article/11733-eng.htm

In children, iodine deficiency can result in various impairments as well as learning disabilities and even low intelligence quotient:

“Children born in iodine deficient areas may have up to 13.5 IQ points less than those born in iodine sufficient areas.” [8]Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html

One of the disorders caused by iodine deficiency is known as “cretinism”: a condition characterized by physical deformity and learning disabilities that is caused by congenital thyroid deficiency.

“We all know that iodine is very important for us, but it has a very specific function, and it’s involved in thyroid function. People who are iodine deficient typically end up with a goitre, which is a thickening around the neck, as you can see in this particular picture here. These people have got thickening of the neck that’s associated with growth in the thyroid, because of the fact that iodine is so important in thyroid properties. But the other thing that’s important is that in the mothers who very severely iodine deficient, the babies are risk of being born with the particular mental disorder known as cretinism. Fortunately, this is now rare, but nonetheless it underpins the importance of the micronutrient in terms of normal physiology and normal function.” [9]McArdle, Harry. Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen, Scotland. Micronutrients. In: Nutrition and Wellbeing. Module 1.14. Accessed March 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/nutrition-wellbeing/13/steps/1000082

Many people have learning disabilities simply owing to a lack of this micronutrient:

“The primary cause of mental retardation in 2013 is lack of iodine, an easily curable mineral deficiency.” [10]Gutiontov, Stanley. Vital amines, purple smoke: A select history of vitamins and minerals. The Pharos/Summer 2014. Pp 18-24.

In 2018, it was estimated to impact nearly 300 million people in this way:

“Reduced mental ability due to IDs occurs in almost 300 million people.” [11]Choudhry, Hani, and Md Nasrullah. “Iodine consumption and cognitive performance: Confirmation of adequate consumption.” Food science & nutrition vol. 6,6 1341-1351. 1 Jun. 2018, doi:10.1002/fsn3.694

But, it’s also a problem if people consume too much iodine. While too little iodine in adults causes “hypothyroidism”, too much causes what is known as “hyperthyroidism”:

“It is important that people obtain enough iodine in their diets… However, having too much iodine in the diet also poses health risks, including hyper- and hypothyroidism and thyroid cancer. This highlights the need for careful consideration of how the policy of salt iodisation is applied, as both too much iodine and too little iodine pose health risks.” [12]Gong, Yun Yun. The challenges of balancing global food safety and nutritional need In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Step 1.12. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1163778

Consequently, population health planners need to estimate regularly on a population level the average iodine intake, and make recommendations that can be used to nudge the trajectory up and down accordingly.

Iodine distributed unevenly on the planet

Iodine was originally widely distributed on the earth’s surface. But over the eons, thanks to glaciation, flooding, and erosion all leeching soil elements in the direction of the oceans, it has become concentrated in the oceans and coastal areas. As a result, “most iodide is found in the oceans. The concentration of iodide in sea water is approximately 50 µg per liter.” [13]Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm

This has led to the earth having iodine-rich and iodine-poor regions. “Iodine concentrations of plants grown in soils of iodine-deficient regions may be as low as 10 μg/kg of dry weight, in contrast to that of plants grown in iodine-rich areas, which may be as high as 1000 μg/kg dry weight.” [14]Leung, Angela M et al. “History of U.S. iodine fortification and supplementation.” Nutrients vol. 4,11 1740-6. 13 Nov. 2012, doi:10.3390/nu4111740

As a result, people in land-locked areas such as Switzerland may be at high-risk of iodine deficiency without public health interventions, while those in live on the ocean and have coastal sea-based diets may consume great amounts of iodine: “Inhabitants of the coastal regions of Japan, whose diets contain large amounts of seaweed, have remarkably high iodine intakes amounting to 50 to 80 mg/day.” [15]Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm

“In some parts of the world, iodine deficiency in the soil results in a deficiency of iodine in the crops used for food. The World Health Organization (WHO) has estimated that over 2 billion people across 130 countries are at risk of low iodine intake.” [16]Gong, Yun Yun. The challenges of balancing global food safety and nutritional need In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Step 1.12. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1163778

How is salt fortified with iodine?

Iodine can be added to salt in one of two forms:

“There are two forms of iodine that can be used to iodize salt: iodide and iodate… Iodate is less soluble and more stable than iodide and is therefore preferred for tropical moist conditions. Both are generally referred to as iodized salt.” [17]Geraldo Medeiros-Neto, and Ileana G.S. Rubio Iodine-Deficiency Disorders. In: Jameson, Larry J., et al, Ed. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric (Seventh Edition). W.B. Saunders. 2017. Chapter 91, Pp 1584-1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-18907-1.00091-3

The iodine present in sea salt is so minuscule that it is of no practical use to your body’s requirements. See: Sea Salt and Iodine

Why was salt chosen to be fortified with iodine?

Salt was chosen as the preferred iodine delivery mechanism because it is easy to fortify, easy to adjust the dosage with, inexpensive to work with for application of the iodine, and is a very commonly used foodstuff through all cuisines in the world.

Salt is a predictable factor in people’s diets that can be inexpensively fortified [18]”In Asia, the cost of iodized salt production and distribution at present is in the order of 3–5 cents per person per year.” Hetzel, B.S. Iodine Deficiency and Its Prevention. In: International Encyclopedia of Public Health (Second Edition). 2017. Pp 336-341. and whose consumption on a population level can be estimated and monitored.

Why is iodized table salt still white?

Iodine is violet-coloured in its pure elemental form.

However, the form of iodine used for salt iodization is not pure, elemental iodine but iodine which has been reacted to form iodide ions. These are colourless, so salts they form such as potassium iodate and potassium iodide are white, and it is these that are applied to salt in the iodization process.

Culinary issues with iodized salt

There are two culinary issues to be aware of if a very high amount of iodine is added to the salt. The first is taste: iodine in larger amounts can, to some people’s tastes, add a harsh flavour to the salt. For this reason, you may prefer to use iodized salts in cooking, but finishing salts at the table for a cleaner taste. The second is that high levels of iodination in salt can inhibit yeast growth in yeast-risen doughs. For this reason, some people prefer to use a non-iodized salt in bread-making. You may find if you do that you can use less yeast.

Salt reduction versus salt as an iodine delivery vehicle

The European Food Information Council advises us not to think that iodine in salt magically makes salt safe to consume in large quantities. Salt is still salt:

“Many countries add iodine to salt (iodised salt), which helps to increase the intake of this mineral. While iodised salt can be a good alternative to regular salt, we should be mindful about our salt intake in general and prioritise other sources of iodine in the diet.” [19]European Food Information Council. Iodine: foods, functions, how much do you need & more. 11 January 2021. Accessed January 2021 at https://www.eufic.org/en/vitamins-and-minerals/article/iodine-foods-functions-how-much-do-you-need-and-more

One issue in recent times is that nutritionists have become increasingly aware of the need to strongly encourage salt intake reduction. In some people’s minds, this makes iodized salt a challenging vehicle to have chosen as the delivery mechanism for iodine:

“The use of salt as a vehicle for fortification is controversial. This is because high salt intake is a risk factor for hypertension and cancer, two of the biggest killers worldwide.” [20]What happens when micronutrient needs aren’t met?. In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Online course. Step 3.9. Accessed August 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1159992

Thus an issue has arisen that as people reduce consumption of salt in response to other health campaigns, their consumption of fortified salt and therefore iodine intake also decreases. “A few recent studies have looked at sodium and iodine, including one in the American Journal of Hypertension that found dietary salt restriction to be associated with iodine deficiency in women.” [21]Baute, Nicole. Health Canada weighs in on table salt. Toronto, Canada: The Toronto Star. 27 October 2010.

This could mean that health organizations and governments need to recommend “increasing iodine levels in table salt so that a smaller amount of salt would confer a comparable health benefit.” [22]Baute, Nicole. Health Canada weighs in on table salt. Toronto, Canada: The Toronto Star. 27 October 2010.

Loss of iodine from iodized salt

Storage in high-humidity conditions can cause the destruction of iodine in iodine-fortified salt, which is why in tropical areas the iodine added is preferred in the form of iodate:

“Iodine is significantly lost upon high humidity storage but light or dry heat has little effect.” [23]Dasgupta P.K., Liu Y., Dyke J.V. Iodine nutrition: Iodine content of iodized salt in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:1315–1323. doi: 10.1021/es0719071.

Cooking with iodized salt results in minimal losses:

“Boiling, baking, and canning of foods manufactured with iodized salt cause only small losses (10%) of iodine content.” [24]Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm

Salt iodization in various countries

Salt iodization is such an important public health programme that an international non-profit, non government organization, the Iodine General Network, is dedicated to championing and coordinating Universal Salt Iodization (USI) around the world.

In large, industrial countries where salt supply is centralized in the hands of a few large producers or importers, implementing iodization can be straightforward.

It can be a challenge in countries with a different salt supply chain structure:

“Other countries may have many small salt farmers scattered over a large area who harvest the product simply and sell it locally. Some progress has been made by iodizing their product through cooperatives and other methods, but with only partial success.” [25]Dunn, John T. Iodine Deficiency. Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases, 2004. Pp 89-99.

Other food vehicles have occasionally been tried, with mixed success, and it could actually be problematic in terms of adverse health outcomes if too many different food items were iodized:

“Many other vehicles have been occasionally used and may have a niche in certain locales. Examples are brick tea, sugar, candy, fried bananas, and fish sauce. For each, one must ask whether its iodization will reach the right part of the population, especially the poor, women, and children, and in the right amounts. A possible danger is that several different forms of iodine supplementation may converge in an individual and produce iodine excess.” [26]Dunn, John T. Iodine Deficiency. Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases, 2004. Pp 89-99.

Salt iodization in Australia

Voluntary. Purchased by less than 10% of the population. Consumers prefer non-iodized salt. Iodine absorbed primarily through dairy products. Some evidence of goiter found in Tasmania & Sydney in 2001/2002. Studies to begin in 2003.

Salt iodization in Canada

Iodization of table salt began in the 1920s and was made mandatory country-wide by law in Canada in 1949. Canada has a particularly high rate (100 ppm / 0.01% / 77 µg/g / 77 g per kg). [27]”All table salt in Canada is iodized with 100 ppm potassium iodide, which corresponds to approximately 77 µg iodine per gram of salt.” [ref]USI ensures adequate iodine intake in Canada. IDD Newsletter. Feb 2013. .

Just 2 grams of salt iodized at this rate “contains approximately the daily recommended amount of 150 mcg iodine.” [28]Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm

Some say the Canadian rate may be excessive, and feel that it makes the taste of the iodized salt quite distinguishably harsh.

Specialty salts (such as sea salt and canning salt) are exempt, but as their sales are such a small fraction of the market, iodized salt consumption is basically 100%.

However, population-healthwise, the intervention has been a success: goiter and other health issues associated with chronic iodine deficiency have been eliminated in Canada to such an extent that there are no longer any official monitoring programmes.

Outside the home in Canada, you will probably find fine restaurants not using iodized salt, fast-food or ordinary places using nothing but, and similarly mixed usage amongst processed food. Some people state that iodized salt is not used in processed food, but that is simply not true. Some processed food will have it, some won’t, and you’ve no way to know as the packaging will just say “salt.”

Salt iodization in India

India initiated a salt iodization programme in 1962 called the National Goitre Control Program. [29]Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html

In 1998, iodisation of consumer salt was made compulsory, but this was repealed shortly afterward on 13 September 2000. [30]Sharma, Dinesh C. Mandatory iodisation of India’s salt ends. London, England: The Lancet. Vol. 356, Issue 9235. 23 September 2000. P. 1090

In 2019, 76.3 percent of households were being reached with salt iodized to at least 15 ppm. [31]Nutrition International, ICCIDD, and Kantar. India Iodine Survey 2018-19 National Report. New Delhi, India. September 2019. P. 4.

The challenges in India identified at the time were to boost this percentage by encouraging more households to consume iodine fortified salt, especially in particular regions such as Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh.

Educating about iodized salt is a challenge identified. Of respondents to India’s 2019 national iodine survey, only about 55% of them had specific awareness of the term “iodized”, and only two-thirds of that 55% had heard of health benefits. At the same time, the government closed the national central office coordinating iodization efforts:

“The central government recently shut down the salt commissioner’s office, which officials say will have far-reaching implications on achieving 100% USI coverage.” [32]Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html

There is the concurrent challenge of reducing salt consumption overall in India: “An average Indian adult consumes about 11 gram of salt per day whereas WHO recommends 5 gm per day.” [33]Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html

Reductions in salt consumption, if achieved, may mean that India may need to revise upwards its salt iodination rate.

Salt iodization in Switzerland

Being in the centre of a continent far from coastal areas, Switzerland is an iodine deficient country. Salt iodization in Switzerland is voluntary but nonetheless has achieved a high diffusion rate in people’s diets:

“Approximately 95% of household salt and 70% of salt for industrial food production in Switzerland is iodized, although iodized salt use is voluntary, and manufacturers and retailers must offer both iodized and noniodized salt.” [34]Zimmermann, Michael B et al. Increasing the iodine concentration in the Swiss iodized salt program markedly improved iodine status in pregnant women and children: a 5-y prospective national study, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 82, Issue 2, August 2005, Pages 388–392, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.2.388

Switzerland has had iodized salt since 1922. The rate began at 3.75 mg per kg. [35]”Iodization of salt was introduced in 1922 at 3.75 mg I per kg. Bürgi, H et al. “Iodine deficiency diseases in Switzerland one hundred years after Theodor Kocher’s survey: a historical review with some new goitre prevalence data.” Acta endocrinologica vol. 123,6 (1990): 577-90. doi:10.1530/acta.0.1230577 Switzerland has maintained over the years an active monitoring of iodine deficiency in its population, and adjusted the iodination rates accordingly. In 1962, the rate in Switzerland was increased to 7.5 mg/kg, in 1980 to 15 mg/kg, and in 1998, to 20 mg/kg. [36]Zimmermann, Michael B et al. Increasing the iodine concentration in the Swiss iodized salt program markedly improved iodine status in pregnant women and children: a 5-y prospective national study, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 82, Issue 2, August 2005, Pages 388–392, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.2.388

Salt iodization in the UK

No official programme. Consumption of iodized salt is minimal. Consumers get iodine through dairy. General population iodine sufficiency.

Salt iodization in the United States

Voluntary. Used by 70% of households. General population iodine sufficiency.

Some studies have shown that some brands of iodized salt may not actually contain the recommended amounts of iodine:

“Fortification of salt with iodine in the U.S. is voluntary, and the FDA does not mandate the listing of iodine content on food packaging. Furthermore, it is assumed that the majority of salt consumption in the U.S. comes from processed foods, in which primarily non-iodized salt is used during production. Although iodized salt in the U.S. is fortified at 45 mg iodide/kg, 47 of 88 table salt brands recently sampled contained less than the FDA’s recommended range of 46–76 mg iodide/kg.” [37]Leung, Angela M et al. “History of U.S. iodine fortification and supplementation.” Nutrients vol. 4,11 1740-6. 13 Nov. 2012, doi:10.3390/nu4111740

History of salt iodination

The iodination of salt was first suggested in 1833 by French scientist Jean Baptiste Boussingault (1802–1887):

“The iodination of salt was first suggested by Boussingault, who lived for many years in Colombia, South America, and discovered that the local people benefit from salt obtained from an abandoned mine in Guaca, Antioquia. In 1825 Boussingault analyzed this salt and found large quantities of iodine. Subsequently, in 1833 he suggested that iodized salt be used for the prevention of goiter.” [38]Kusić, Zvonko, and Tomislav Jukić. “History of endemic goiter in Croatia: from severe iodine deficiency to iodine sufficiency.” Collegium antropologicum vol. 29,1 (2005): 9-16.

It would not be, however, until 1922 that iodination of salt became public policy. Iodine, in fact, was the very first food element to be commercially added to food as a supplement. In 1922, Switzerland became the first country to require iodination of salt:

“The Swiss Commission of Goiter met for the first time the 21st of January, 1922 and has been the first step of an historical event in terms of Public Health: the first requirement for salt iodination for the prevention of goiter.” [39]Bonnemain, B. “La Commission suisse du goitre du 21 janvier 1922, une séance historique quant á l’usage du sel iodé en Suisse et dans les pays occidentaux” [The Swiss Commission of Goiter of January 21, 1922]. Revue d’histoire de la pharmacie vol. 49,332 (2001): 533-40.

Iodination of salt in North America began in Michigan in 1924, at the behest of a Canadian doctor, David Murray Cowie, who was a Professor of Pediatrics at the University of Michigan.

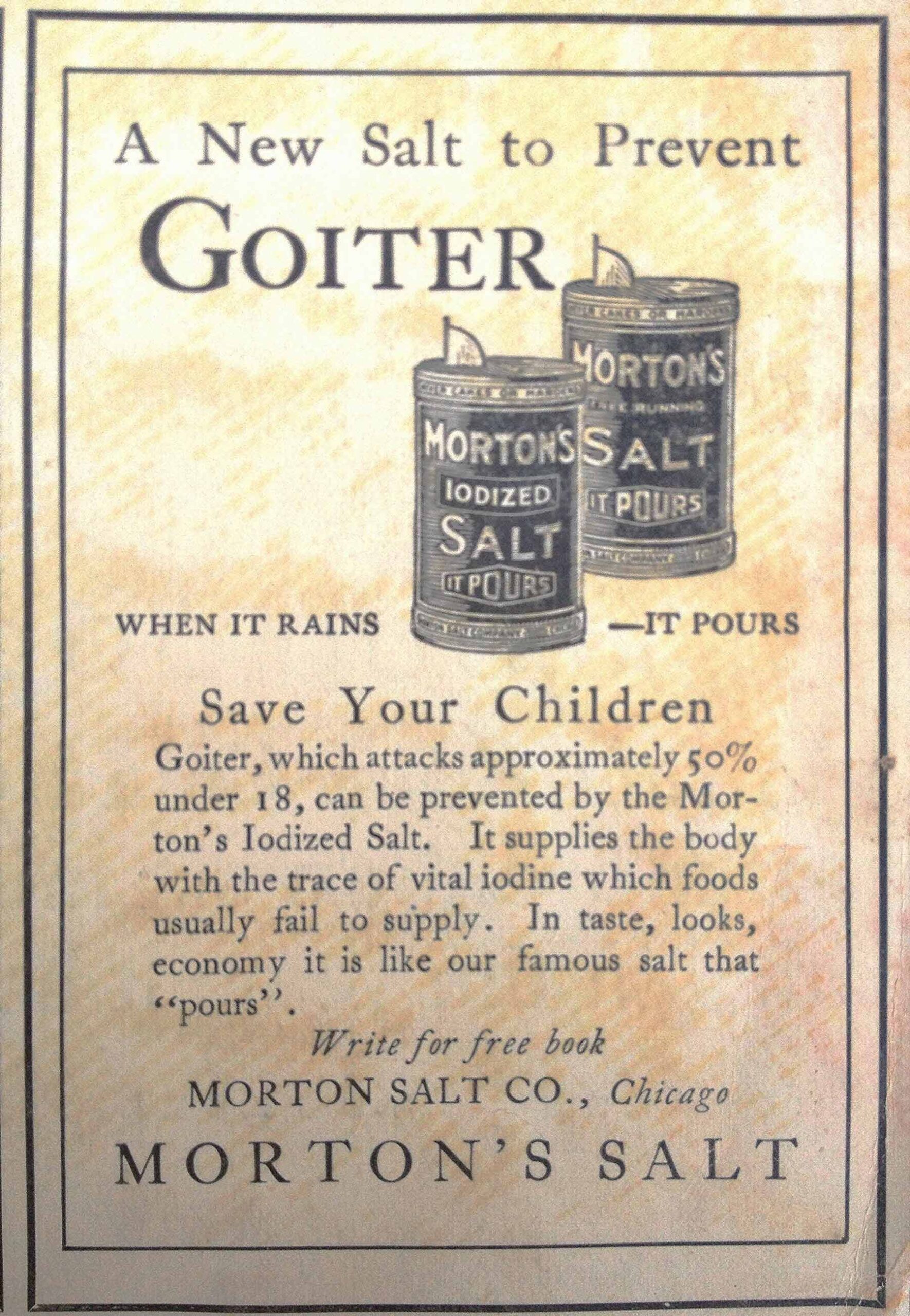

“Iodized salt produced by the Diamond Crystal Salt, Mulkey Salt, Inland-Delray Salt, Michigan Salt Works, and Ruggles and Rademaker companies first appeared on the Michigan grocers’ shelves on May 1, 1924. The Morton Salt Company began producing and selling iodized salt in the fall of 1924, four months after the iodized salt committee of the Michigan State Medical Society made its formal endorsement and the firm was satisfied that iodized salt could be sold on a national market. [40]Markel, Howard. “When it Rains it Pours”: Endemic Goiter, Iodized Salt, and David Murray Cowie, MD. American Journal of Public Health. February 1987. Vol 77, No. 2. Page 224.

By 1935, iodized salt sales made up 90% of the salt sales in Michigan, and there was an accompanying dramatic decline in goiter. And rather than seeing iodination as a nuisance, salt companies advertised it as a feature to promote their offerings as a health product, and increase sales.

Morton’s iodized salt ad, 1920s.

Language notes

Iodine is named after “Ιώδης” (iodes), the classical Greek word for “violet”.

Both “iodized” and “iodised” are acceptable spellings in English.

Further reading

EUFIC. Iodine: foods, functions, how much do you need & more. 11 January 2021.

Gutiontov, Stanley. Vital amines, purple smoke: A select history of vitamins and minerals. The Pharos/Summer 2014. Pp 18-24.

Markel, Howard. “When it Rains it Pours”: Endemic Goiter, Iodized Salt, and

David Murray Cowie, MD. American Journal of Public Health. February 1987. Vol 77, No. 2.

Purnendu K. Dasgupta, Yining Liu, and Jason V. Dyke. Iodine Nutrition: Iodine Content of Iodized Salt in the United States. Environmental Science & Technology 2008 42 (4), 1315-1323. DOI: 10.1021/es0719071

World Health Organization. Goitre as a determinant of the prevalence and severity of iodine deficiency disorders in populations. 2014.

References

| ↑1 | EUFIC. Iodine: foods, functions, how much do you need & more. 11 January 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.eufic.org/en/vitamins-and-minerals/article/iodine-foods-functions-how-much-do-you-need-and-more |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm |

| ↑3 | Leung, Angela M et al. “History of U.S. iodine fortification and supplementation.” Nutrients vol. 4,11 1740-6. 13 Nov. 2012, doi:10.3390/nu4111740 |

| ↑4 | (Note: these are estimates from the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). Consult your physician and local health authorities.) EUFIC. Iodine: foods, functions, how much do you need & more. 11 January 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.eufic.org/en/vitamins-and-minerals/article/iodine-foods-functions-how-much-do-you-need-and-more |

| ↑5 | What happens when micronutrient needs aren’t met?. In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Online course. Step 3.9. Accessed August 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1159992 |

| ↑6 | Gong, Yun Yun. The challenges of balancing global food safety and nutritional need In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Step 1.12. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1163778 |

| ↑7 | Iodine status of Canadians, 2009 to 2011. Statistics Canada. 29 November 2012. Accessed November 2022 at https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-625-x/2012001/article/11733-eng.htm |

| ↑8 | Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html |

| ↑9 | McArdle, Harry. Rowett Institute of Nutrition and Health, University of Aberdeen, Scotland. Micronutrients. In: Nutrition and Wellbeing. Module 1.14. Accessed March 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/nutrition-wellbeing/13/steps/1000082 |

| ↑10 | Gutiontov, Stanley. Vital amines, purple smoke: A select history of vitamins and minerals. The Pharos/Summer 2014. Pp 18-24. |

| ↑11 | Choudhry, Hani, and Md Nasrullah. “Iodine consumption and cognitive performance: Confirmation of adequate consumption.” Food science & nutrition vol. 6,6 1341-1351. 1 Jun. 2018, doi:10.1002/fsn3.694 |

| ↑12 | Gong, Yun Yun. The challenges of balancing global food safety and nutritional need In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Step 1.12. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1163778 |

| ↑13 | Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm |

| ↑14 | Leung, Angela M et al. “History of U.S. iodine fortification and supplementation.” Nutrients vol. 4,11 1740-6. 13 Nov. 2012, doi:10.3390/nu4111740 |

| ↑15 | Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm |

| ↑16 | Gong, Yun Yun. The challenges of balancing global food safety and nutritional need In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Step 1.12. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1163778 |

| ↑17 | Geraldo Medeiros-Neto, and Ileana G.S. Rubio Iodine-Deficiency Disorders. In: Jameson, Larry J., et al, Ed. Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric (Seventh Edition). W.B. Saunders. 2017. Chapter 91, Pp 1584-1600. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-18907-1.00091-3 |

| ↑18 | ”In Asia, the cost of iodized salt production and distribution at present is in the order of 3–5 cents per person per year.” Hetzel, B.S. Iodine Deficiency and Its Prevention. In: International Encyclopedia of Public Health (Second Edition). 2017. Pp 336-341. |

| ↑19 | European Food Information Council. Iodine: foods, functions, how much do you need & more. 11 January 2021. Accessed January 2021 at https://www.eufic.org/en/vitamins-and-minerals/article/iodine-foods-functions-how-much-do-you-need-and-more |

| ↑20 | What happens when micronutrient needs aren’t met?. In: Food Safety and Nutrition: A Global Approach to Public Health. University of Leeds. Online course. Step 3.9. Accessed August 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/global-food-safety-and-nutrition/1/steps/1159992 |

| ↑21 | Baute, Nicole. Health Canada weighs in on table salt. Toronto, Canada: The Toronto Star. 27 October 2010. |

| ↑22 | Baute, Nicole. Health Canada weighs in on table salt. Toronto, Canada: The Toronto Star. 27 October 2010. |

| ↑23 | Dasgupta P.K., Liu Y., Dyke J.V. Iodine nutrition: Iodine content of iodized salt in the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008;42:1315–1323. doi: 10.1021/es0719071. |

| ↑24 | Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm |

| ↑25 | Dunn, John T. Iodine Deficiency. Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases, 2004. Pp 89-99. |

| ↑26 | Dunn, John T. Iodine Deficiency. Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases, 2004. Pp 89-99. |

| ↑27 | ”All table salt in Canada is iodized with 100 ppm potassium iodide, which corresponds to approximately 77 µg iodine per gram of salt.” [ref]USI ensures adequate iodine intake in Canada. IDD Newsletter. Feb 2013. |

| ↑28 | Where do we get iodine from? Iodine Global Network. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.ign.org/4-where-do-we-get-iodine-from.htm |

| ↑29 | Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html |

| ↑30 | Sharma, Dinesh C. Mandatory iodisation of India’s salt ends. London, England: The Lancet. Vol. 356, Issue 9235. 23 September 2000. P. 1090 |

| ↑31 | Nutrition International, ICCIDD, and Kantar. India Iodine Survey 2018-19 National Report. New Delhi, India. September 2019. P. 4. |

| ↑32 | Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html |

| ↑33 | Sharma, Neetu Chandra. Why India should revisit its food Iodine programme after pandemic. New Delhi, India: Mint Newspaper. 5 July 2021. Accessed March 2022 at https://www.livemint.com/news/india/why-should-india-revisit-its-food-iodine-programme-after-pandemic-11625469128805.html |

| ↑34 | Zimmermann, Michael B et al. Increasing the iodine concentration in the Swiss iodized salt program markedly improved iodine status in pregnant women and children: a 5-y prospective national study, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 82, Issue 2, August 2005, Pages 388–392, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.2.388 |

| ↑35 | ”Iodization of salt was introduced in 1922 at 3.75 mg I per kg. Bürgi, H et al. “Iodine deficiency diseases in Switzerland one hundred years after Theodor Kocher’s survey: a historical review with some new goitre prevalence data.” Acta endocrinologica vol. 123,6 (1990): 577-90. doi:10.1530/acta.0.1230577 |

| ↑36 | Zimmermann, Michael B et al. Increasing the iodine concentration in the Swiss iodized salt program markedly improved iodine status in pregnant women and children: a 5-y prospective national study, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 82, Issue 2, August 2005, Pages 388–392, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/82.2.388 |

| ↑37 | Leung, Angela M et al. “History of U.S. iodine fortification and supplementation.” Nutrients vol. 4,11 1740-6. 13 Nov. 2012, doi:10.3390/nu4111740 |

| ↑38 | Kusić, Zvonko, and Tomislav Jukić. “History of endemic goiter in Croatia: from severe iodine deficiency to iodine sufficiency.” Collegium antropologicum vol. 29,1 (2005): 9-16. |

| ↑39 | Bonnemain, B. “La Commission suisse du goitre du 21 janvier 1922, une séance historique quant á l’usage du sel iodé en Suisse et dans les pays occidentaux” [The Swiss Commission of Goiter of January 21, 1922]. Revue d’histoire de la pharmacie vol. 49,332 (2001): 533-40. |

| ↑40 | Markel, Howard. “When it Rains it Pours”: Endemic Goiter, Iodized Salt, and David Murray Cowie, MD. American Journal of Public Health. February 1987. Vol 77, No. 2. Page 224. |