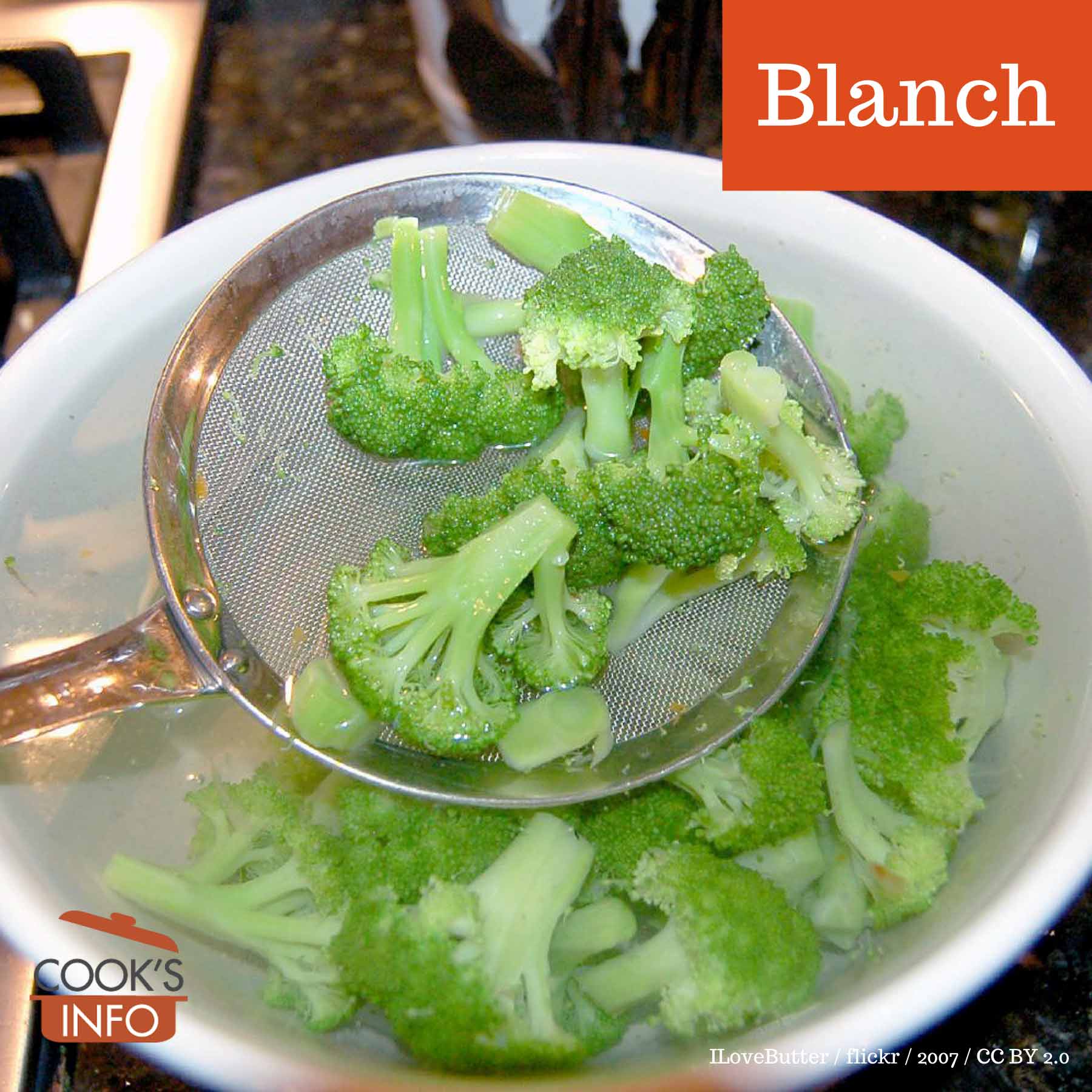

Blanched broccoli in cold water. ILoveButter / flickr / 2007 / CC BY 2.0

“To blanch” means to very briefly flash-heat produce (typically vegetables but sometimes fruit). Unless the next step of processing is more heat treatment, as is the case with canning, the produce that was just blanched is then rapid cooling. In home kitchens, the heating is typically done in boiling water; the cooling is typically done in very cold water (industrially, the cooling may be done through spraying with cold water or air.)

Blanch can also be used in a sense that is actually much closer to what it really means, which is to “make white.” It’s the process by which produce such as Belgian Endive, White Asparagus, Seakale and Champagne Rhubarb are grown, deprived of light, so that they don’t develop any colour. The process keeps the flavour more delicate.

Asparagus being blanched in the field. pxfuel.com / CC0 1.0

Reasons for blanching

Blanching in the kitchen can be done for varying reasons:

- Prepare vegetables for freezing and longer storage life. The scalding destroys enzymes which are otherwise “programmed” to decompose the produce and destroy its nutritional value and eventually its appearance and texture;

- Reduces volume size of produce by driving air out, allowing more to be packed into intended containers;

- Make it easier to peel some items (such as almonds, peaches and tomatoes);

- Develop a bit of taste in a vegetable otherwise intended to be served raw (this is also called parboiling);

- Removes some dirt and microorganisms on the surface of foods;

- Make the taste of produce such as garlic or kale milder, or to make meats such as salt pork or bacon less salty.

Which enzymes exactly does blanching for food preservation target

For food preservation, and in particular freezing, the principle enzymes of concern are catalase, chlorophyllase, lipoxygenase, peroxidase, polyphenoloxidase, and polygalacturonase.

Of these, lipoxygenease is the one most commonly responsible for off-flavours. [1]Lee, Y. C.. “Lipoxygenase and Off-flavor Development in Some Frozen Foods.” Korean Journal of Food Science and Technology 13 (1981): 53-56.

Catalase and peroxidase are the most heat-resistant ones, so they are the ones tracked to determine whether the blanching period has been sufficient. [2]”Peroxidase and catalase are the most commonly assayedenzymes for blanching before freezing because they are more resistant to heat than most enzymes, and there aresimple rapid assays to measure their activity.” Reyes, José & Reyes-De-Corcuera, Jose & Cavalieri, Ralph & Powers, Joseph. (2021). Blanching of Foods. [3]Ramaswamy, Hosahalli S.; Marcotte, Michelle (2006). Food processing : principles and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press

There has been some debate recently in the food science community as to whether controlling for these two enzymes has led to some overly-long blanching times for some produce. [4]”Blanching until total peroxidise inactivation generally implies over-processing with consequent unnecessary quality losses.” — Severini, C et al. “Influence of different blanching methods on colour, ascorbic acid and phenolics content of broccoli.” Journal of food science and technology vol. 53,1 (2016): 501-10. doi:10.1007/s13197-015-1878-0.

Freezing slows enzymes down but does not inactivate them. This means that the spoilage they cause can slowly continue in the freezer:

“If vegetables are not heated sufficiently, the enzymes will continue to be active during frozen storage.” [5]Barbosa-Cánovas, Gustavo V., Bilge Altunakar, and Danilo J. Mejía-Lorio. Freezing of fruits and Vegetables. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. 2005. Chapter 1, section 1.3.2.

How to blanch water produce

Put produce into water that is already boiling. In order to prevent the boil from dying back completely when the produce is added, use about 1 gallon of water per 1 pound of prepared vegetables (4 litres of water per 500 g of veg.) To be clear, the water is unsalted.

Keep heat on high for full length of blanching time.

Start counting the blanching time from when the water returns to a full boil, which should be in 1 minute or under.

Place a lid on the pot during blanching.

“Use one gallon water per pound of prepared vegetables. Put the vegetable in a blanching basket and lower into vigorously boiling water. Place a lid on the blancher. The water should return to boiling within 1 minute, or you are using too much vegetable for the amount of boiling water. Start counting blanching time as soon as the water returns to a boil.” [6] Andress, Elizabeth L. and Judy A. Harrison. So Easy to Preserve. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Bulletin 989. Sixth Edition. 2014. Page 277.

When the time is up, remove food being blanched with a slotted spoon or drain them by another method, and plunge them a very large bowl, pot or vessel full of water as cold as you can get it — at least 15 C (60 F) or colder. [7]Ibid. Page 278. Allow the produce to chill for a number of minutes equal to the time that you blanched it for, then drain, pack and freeze. It’s important to drain thoroughly. Excess water left on can cause damage during freezing. You may even wish to pat dry on tea towels, if the nature of the produce permits.

“As soon as blanching is complete, vegetables should be cooled quickly and thoroughly to stop the cooking process. To cool, plunge the basket of vegetables immediately into a large quantity of cold water, 60ºF (15 C) or below. Change water frequently or use cold running water or ice water. If ice is used, about one pound of ice for each pound of vegetable is needed. Cooling vegetables should take the same amount of time as blanching. Drain vegetables thoroughly after cooling. Extra moisture can cause a loss of quality when vegetables are frozen.” [8]Ibid. Page 278.

Steam blanching is recommend for more delicate items such as grated zucchini or sprouts.

Onions, mushrooms and green peppers don’t need to be blanched before freezing.

You don’t want to under blanch or over blanch; times vary according to what you are processing. There are tables giving you times which have actually been lab-tested for optimum efficacy (see Resources below).

“Underblanching stimulates the activity of enzymes and is worse than no blanching. Overblanching causes loss of flavor, color, vitamins and minerals.” [9]Ibid. Page 277.

Microwave blanching

Some university research has found that microwave blanching doesn’t always destroy all the enzymes that should be rendered ineffective before freezing vegetables. The studies did find, however, that in terms of energy being used, there are no energy savings to be realized by microwaving versus boiling.

“Microwave blanching may not be effective, since research shows that some enzymes may not be inactivated. This could result in off-flavors and loss of texture and color. Those choosing to run the risk of low quality vegetables by microwave blanching should be sure to work in small quantities, using the directions for their specific microwave oven. Microwave blanching will not save time or energy.” [10]Ibid. Page 278.

The authors of a 2015 Italian study, however, felt that there was still promise in further studying microwave blanching:

“Time necessary to enzymes inactivation by microwave was higher than that by steam but lower than that by hot water. In conclusion, this technology, if appropriately used as blanching method, could benefit the industry by decreasing water use, clean up costs, energy costs and would result in a more desirable product in terms of retention of nutrients.” [11]Severini, C et al. “Influence of different blanching methods on colour, ascorbic acid and phenolics content of broccoli.” Journal of food science and technology vol. 53,1 (2016): 501-10. doi:10.1007/s13197-015-1878-0.

An issue with developing any further recommendations for home microwave blanching could be that home microwave oven design and power vary so widely that it could be an impossible task arriving at standardized recommendations, let along keeping them up to date with changing equipment. It’s possible that microwave blanching may be perfected for some uses in industry, where standardization of equipment and therefore guidelines is more feasible.

Further blanching resources

These links take you to in-depth material on our home food preservation site, including tables for blanching times.

Blanching (including steam blanching)

Blanching times for fruit to be dried

Blanching times for vegetables to be dried

Blanching times for vegetables to be frozen

Hong-Wei Xiao, Zhongli Pan, Li-Zhen Deng, Hamed M. El-Mashad, Xu-Hai Yang, Arun S. Mujumdar, Zhen-Jiang Gao, Qian Zhang. Recent developments and trends in thermal blanching – A comprehensive review. Information Processing in Agriculture, Volume 4, Issue 2, 2017. Pages 101-127. ISSN 2214-3173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inpa.2017.02.001.

Language Notes

The English verb “to blanch” comes from the French verb, “blanchir”, which means to turn white. The verb in turn comes from the French word for white, blanc (in fact, the feminine version of the word, which is “blanche”.)

References

| ↑1 | Lee, Y. C.. “Lipoxygenase and Off-flavor Development in Some Frozen Foods.” Korean Journal of Food Science and Technology 13 (1981): 53-56. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | ”Peroxidase and catalase are the most commonly assayedenzymes for blanching before freezing because they are more resistant to heat than most enzymes, and there aresimple rapid assays to measure their activity.” Reyes, José & Reyes-De-Corcuera, Jose & Cavalieri, Ralph & Powers, Joseph. (2021). Blanching of Foods. |

| ↑3 | Ramaswamy, Hosahalli S.; Marcotte, Michelle (2006). Food processing : principles and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press |

| ↑4 | ”Blanching until total peroxidise inactivation generally implies over-processing with consequent unnecessary quality losses.” — Severini, C et al. “Influence of different blanching methods on colour, ascorbic acid and phenolics content of broccoli.” Journal of food science and technology vol. 53,1 (2016): 501-10. doi:10.1007/s13197-015-1878-0. |

| ↑5 | Barbosa-Cánovas, Gustavo V., Bilge Altunakar, and Danilo J. Mejía-Lorio. Freezing of fruits and Vegetables. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. 2005. Chapter 1, section 1.3.2. |

| ↑6 | Andress, Elizabeth L. and Judy A. Harrison. So Easy to Preserve. University of Georgia Cooperative Extension. Bulletin 989. Sixth Edition. 2014. Page 277. |

| ↑7 | Ibid. Page 278. |

| ↑8 | Ibid. Page 278. |

| ↑9 | Ibid. Page 277. |

| ↑10 | Ibid. Page 278. |

| ↑11 | Severini, C et al. “Influence of different blanching methods on colour, ascorbic acid and phenolics content of broccoli.” Journal of food science and technology vol. 53,1 (2016): 501-10. doi:10.1007/s13197-015-1878-0. |