© Denzil Green

- 1 Tea vs coffee

- 2 Dairy in Britain

- 3 British Sauces

- 4 Vegetarianism in Britain

- 5 Wine in Britain

- 6 History Notes

- 7 British Food in The Puritan Era

- 8 British Food in the 1700s

- 9 British Food in The Victorian Era

- 10 British Food in WWI

- 11 British Food in WWII

- 12 British Food in the second half of the 1900s

- 13 Literature & Lore

- 14 Sources

North Americans pat themselves on the back for having revolutionised their cooking in the past few decades. Pasta, olive oil and designer sea salts are now taken completely for granted. They feel even more on top of the world when they make jokes about British food. The jokes are based on the assumption that while North American food has moved ahead, British cooking has stayed where it was during war-time rationing.

The reality is that not only has British food not stood still, it has leapfrogged North American food in variety, quality, excitement and affordability. North Americans are loathe to even admit this into the realm of possibility, because it disrupts one of their cherished world views. You have to drag them over into British supermarkets, where they stand in stunned disbelief.

British supermarkets have become temples of food, with dairy shelves groaning with cheeses from all corners of Europe, and at prices that would make many North Americans, particularly Canadians, weep. The price of dairy products in Britain is about ½ to ⅓ that of what they are in Canada since Britain abolished its marketing boards that had held innovation low and prices high. Brits, in fact, shopping for groceries in Canada, are quietly disappointed by the lack of choice, but openly shocked about how much more all groceries cost, even with their favourable exchange rate.

The myth about British food being expensive comes from tourists eating at tourist traps in London. We all have places in our own cities where we know the locals won’t pay the prices they want, that only tourists will, but for some reason people presume that people in London happily pay 10 bucks for a sandwich — which of course they won’t.

Nor have people equated the flood of British cooking shows on TV in North America with any possible changes on the British food scene that might cause them to revisit their hoary old cherished conceptions. But never mind. The British food scene has been abuzz since the early 1980s, as personal incomes finally increased and policy changes allowed innovation to flourish. British cookbooks have become lavish enough to become coffee table books. But North Americans still harbour images of British food as being boiled and flavourless, even though many of their own basic products, such as bacon and sausage, taste exactly just that compared to what’s available in the UK today.

The French, of course, will always continue to slag British food, but then, they slag every food in the world that isn’t French. And it’s true that historically, British country cooking was never as good as French country cooking. Nevertheless, even the French have adopted some British foods such as steaks, and sandwiches, and admire the British pies, puddings and custards. British custard has inspired many French desserts over the past few hundred years.

The British were aware that their food needed to improve, and so have not only worked at it, but been open to other foods and cuisines, incorporating them into their culinary universe. This has given them a modern edge over many other cultures on the other side of the English channel. Some people talked about improving British food, but they were largely toney people aiming their remarks at other toney people, and actually thinking more about restaurant food and getting access to foreign food in Britain that they missed from their holidays abroad. They weren’t thinking about improving “native” British foods or the food of ordinary people.

The French, on the other hand, were very chauvinistic about their food, and took it for granted, with the situation then becoming such that while the level of food in the British household is increasing, in France it is decreasing. British supermarkets offer a higher quality of food and a far greater range than do French supermarkets, with the result that while both British and French shoppers are going to supermarkets and not to farmer markets, the busy British foodie ends up with better food in the cart. French supermarket owners and managers complain in return that customers either no longer understand products, or are obsessed with diets, cholesterol, cardiac illnesses, etc, without even really understanding health matters and just going by what the latest scare is that’s being parroted by the media.

In February 2005, Gourmet Magazine proclaimed that London had become the best place to eat in the world. The editors said the state of British food was a revelation. The entire issue was dedicated to London, which was the first time the magazine had ever done anything like that. They said that England had high-quality food at all levels, from the supermarket aisle to the fanciest restaurant.

East Anglia produces many of the vegetables in England destined for freezing and canning, while the south-east of England produces many vegetables to be sold fresh at markets and stores.

The English have always judged cooking by the quality of the beef, whereas the French and Italians judge on the quality of the bread.

London’s oldest still-operating restaurant, named “Rules”, was opened in 1798 by Thomas Rule. It is still in its original location in Covent Garden.

North Americans will never understand the British love for toast racks.

Britain has been dependent on imported food for several hundred years. The trend was slightly reversed during World War Two, but has increased since then. From 1997 to 2011, the acreage given over to orchards in Britain declined by 33%, while overall the land used for fresh fruit and veg fell by 23%. In total, 170,000 acres of farm and orchard land went out of production. [1]Wallop, Harry. Cox apple toppled by the gala. London: Daily Telegraph. 13 March 2011.

Tea vs coffee

When the first shipment of tea arrived in England in the 1660s, coffeehouses were already well established. Tea was heavily taxed, so it did not become immediately widely popular.

By the mid-1800s, cheaper tea from British colonies in Sri Lanka and India were arriving, helping to make tea more broadly popular as a drink amongst even the poorer classes.

William Cobbett railed against tea replacing ale as a drink (as well as against the introduction of commercially-brewed beer rather than home-brewed beer.)

As of 2021, 96% of tea-drinkers in the UK make their tea with a teabag. 98% of people in the UK drink tea with milk. Just 30% of U.K. adults like sugar with their tea. [2]A nice cup of tea. In: Exploring English Food and Culture. The British Council. Module 4.7. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/exploring-english-food-and-culture/1/steps/1185275

Use of tea bags in the U.K. did not take off until the 1970s. [3]”Tea bags were invented in America in the early twentieth century, but sales only really took off in Britain in the 1970s.” — UK Tea and Infusions Association. Modern Tea Drinking. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.tea.co.uk/history-of-tea

In the 1990s, coffee began making a comeback in England as chains such as Costa and Starbucks appeared serving Italian-style coffees.

As of 2021, 100 million cups of tea a day are drunk in the U.K. compared to 70 million cups of coffee. [4]A nice cup of tea. In: Exploring English Food and Culture. The British Council. Module 4.7. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/exploring-english-food-and-culture/1/steps/1185275

Dairy in Britain

The British Milk Marketing Board was established in 1933; abolished 1 November 1994. It was given the statutory right to market all milk produced in England and Wales. It was “owned by the producers”, who were nevertheless also compelled to pay a levy to it. In the 1980s, British cheese was industrial and flavourless. But by 2002, there were over 450 different specialty cheeses available in Britain, many produced by small operations using traditional methods.

In January 2002, The Food Standards Agency launched an educational effort in cooperation with the Specialist Cheesemaker’s Association to help them apply modern food safety standards to their cheeses, and aimed at reducing the paperwork involved.

The Scottish Highlands produce mostly soft cheeses.

British Sauces

For meat: bread sauce (dates from the Middle Ages), Mint Sauce (which the French look on with horror, but which dates from the Romans), and horseradish sauce;

- For fish; parsley sauce;

- For veg: cheese sauce;

- For desserts: custard sauce and hard sauces.

Vegetarianism in Britain

Vegetarianism is more organised and visible in England than in North America. There is a standard vegetarian symbol that appears beside vegetarian dishes on menus, and grocery stores have far more prepared vegetarian foods than in North America. British vegetarians coming to North America are usually dismayed at the low level of choice and high level of cost there.

Wine in Britain

Grapes are being grown again in Essex, Kent, Hampshire and Sussex, replacing less profitable crops of hops and wheat. Sussex is just shy of 90 miles (145 km) north as the crow files from the Champagne area in France, and its temperature on average is just about the same, with the same chalky soil. Initially, the assumption was that German grapes would do best, but in the mid-1990s, there was a shift to French grapes. Some English wines are starting to win prizes at shows. In 2004, nearly 3 million bottles of English wine were produced.

In the South-west of England, and in the counties of Herefordshire and Gloucestershire, cider is made from cider apples. In the county of Kent, however, it is usually made from cooking and eating apples that are also good for cider.

History Notes

Medieval English cooking, like European cooking, was highly spiced, using many of the same ingredients that are used in Indian curry today.

The first cookbook published in England was “The Forme of Cury” in 1390 with 196 recipes. “Cury” meant cooking. It came from the French word “cuire.”

It was traditional in the Catholic Church to have “meatless Fridays”, on which Fish was eaten instead of meat. After the Anglican Church in England broke off from the Catholic Church, Fish consumption dropped dramatically, though avoiding meat on Fridays was still Anglican “official” policy. To bolster the fish market, English authorities tried twice to re-instate meatless days. In 1548, they tried to make it Saturdays, and in 1563, they tried to make it Wednesdays. Neither attempt was successful: in fact, it is Fridays that still remain the big day for fish and chip shops throughout Britain. The famous fish market in London was Billingsgate in the City of London. In 1982, the market moved to the Docklands in London.

On 13th February 1933, a bill that would have introduced Prohibition throughout the United Kingdom was defeated in the House of Commons.

British Food in The Puritan Era

The mean-spiritedness of the Puritan era in England (1649 – 1660) is well-known, with Christmas Day and even Christmas Pudding being banned, but Oliver Cromwell appeared to live by the same standard himself, at least in regards to food. Thomas Milbourne, in his 1664 book “The Court and Kitchin of Elizabeth (Cromwell)” mocks how miserly Cromwell’s wife Elizabeth was with state funds. She was allotted “only” £1,000 to spend on a state banquet for the French Ambassador — but still found savings of £200 pounds within that budget. Elizabeth Cromwell made sure that all food not used at banquets was distributed to the poor. When her husband, Oliver Cromwell, asked for an orange to go with his veal, Elizabeth told him that he couldn’t have one, as they were too expensive just then. While the Puritan reign was no sunny place in England’s history, and Milbourne’s intention was certainly to mock the Cromwells for living so modestly, it’s hard to imagine many in government today being quite as careful with public funds.

British Food in the 1700s

In the 1700s, French cookbooks sought to codify cooking as a high art form, and were written by men. British cookbooks of the same era were written by women, and contained practical advice about how to manage in the kitchen.

In the 1700s, the English were complaining that the French didn’t know how to cook beef – that they were always boiling it, and when they did roast it, they roasted it in pieces too small so that they couldn’t cook properly. The French noted that wealthier English of the time cooked roasts 20 or 30 pounds (9 to 13 kg) and up. But the French were actually more advanced than the English at this point, because it shows that they were starting to understand meat cuts, thus the smaller pieces.

By the time of the French Revolution, France was the world’s leading producer of sugar owing to its possession of island of Santo Domingo. By 1790, French eating 1.8 pounds (800 g) of sugar per head per year. The English, though, were way ahead of them — they were eating 15 ½ pounds (7 kg) of sugar per capita a year in 1792.

British Food in The Victorian Era

The poor in Victorian London often had no stove at home to cook on.

You could eat breakfast at a street stall — bread and butter, with a mug of hot milk with gin in it. Street vendors served lunch and dinner as well. They sold food such as oysters, winkles and savoury pies, which could be bought for a penny from them. You couldn’t always be sure, though, of what meat was in the pies,

Cucumber was popular, until a rumour spread that it carried cholera (the carrier turned out to be, in fact, watercress.)

British Food in WWI

In 1913, the year before the war began, the British consumed 130 pounds of meat per person per year, compared to 105 pounds for the French, and 99 pounds for the Germans.

The concept of a war being fought on the “home front” emerged in Britain during WWI. The “Win the War Cookery Book”, edited by Edgar Jepson, said “The struggle is not only on land and sea; it is in your larder, your kitchen and your dining room.” Eating margarine was seen as patriotic. The British Women’s Patriotic League said that people could show themselves as being patriotic by buying “British or Empire made goods.”

British Food in WWII

See also separate in-depth article on British Wartime Food. This section is a high-level summary.

During the Second World War, price controls were introduced first on fish, then on tomatoes, then on fruit.

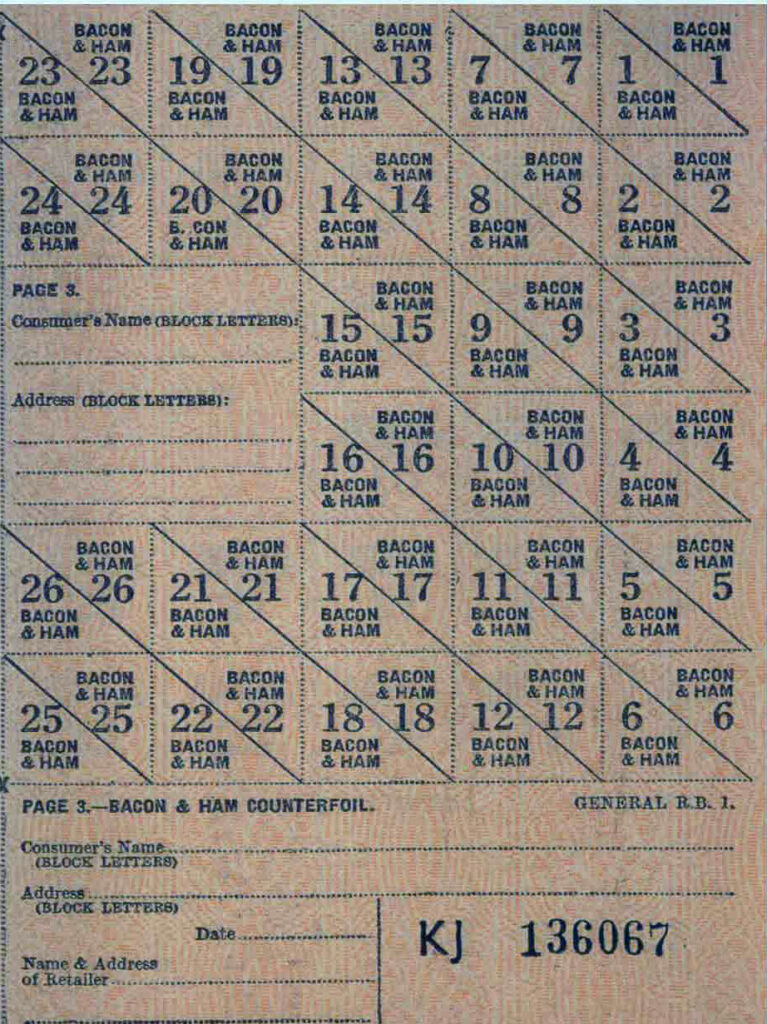

The British had to learn to cook from ration coupons. Ration coupons, however, still didn’t guarantee that an item would be available, or of decent quality, or that you would have the money to actually pay for it. To use your ration coupons, you had to register with a grocery store, and with a butcher, and use them at those stores.

British grocery stores, too, had to adjust to war. Some, such as Sainsbury’s, as soon as war was declared on 9 September 1939, began to recruit female stuff to replace male staff whom, they assumed, would soon be called up for the war effort. Some of the female staff were lost, too, when the government began calling up females in the 20 to 21 age group. Sales in London grocery stores fell as evacuations of women and children began from London in anticipation of the bombing to come.

People had to bring their own wrappings for food to the grocery stores. The store would provide some waxed paper or white paper for one layer of wrapping, but the customer would need to supply something like newspaper for more wrapping on top of that. If the butcher was short of fresh meat to make up your ration, he was allowed to supply corned beef to top it up. Tripe was cheap and plentiful in the UK during the Second World War, because even the fact that there was no other meat available still didn’t make people want tripe.

Some fish and chip shops asked people to bring something to put their fish and chips in as well.

The diet controlled by the Ministry of Food was nutritious and balanced, even though it was bland and uninteresting. Many say the health of the British people was never as good previously, or hasn’t been since rationing. Children ate more bread, milk and vegetables than they do today.

People such as Marguerite Patten, who were later to become food writers, were hired to work for the Ministry to inspire people about how to cook with what was available to them. To help promote the ideas, the Ministry of Food even opened an office in Harrod’s, as well as a kitchen in the store to do demonstrations.

The Ministry recommended slicing meat very thinly, and covering it with gravy

It oversaw the mass production of a “National Loaf” of bread that was officially called “wheatmeal”. It was wholemeal (whole grain) bread. Despite the government assuring people that it was healthier (which it was), it was strongly disliked.

Dried eggs replaced fresh eggs, one tin per family. New recipes emerged on how to cook with the powdered egg.

Orange juice was available for children, but not for adults.

Whale meat could be had abundantly, but no one wanted it, as no amount of boiling, rinsing and boiling could get rid of the smell and taste.

People in the countryside ate better than those in the countries. They had more garden space, so they could grow things for barter, and keep chickens.

In the middle of May 1944, the bacon ration was increased from 4 to 6 oz (115 to 170 g) per week.

Rationing continued long after the war, until 1956.

In November 1947, the Queen was married to Prince Philip, but only after assembling enough ration coupons to allow material for the dress. People from across the country donated material ration coupons to help out. [2]

In June 1953, the month that the Queen was crowned, everyone got an extra 1 pound (450 g) of sugar and 4 oz (115 g) of margarine. Eggs had just come off ration; meat and butter were still on ration. Meat and bacon came off ration in June 1954.

British Food in the second half of the 1900s

During the 1950s, there were no fresh beans, peas or leafy vegetables during the winter.

At the start of the 50s, tropical fruits such as bananas and citrus fruit began to slowly reappear in stores.

Most food still sold loose, and was weighed and measured at point of sale. People would shop each day, not only to get stuff as it became available, but also because there was no refrigeration. Refrigerators were still not common in homes in Britain.

Even though Elizabeth David started writing about exotic foods in the 1950s, the cost of what she was writing about would have been out of reach for almost all Brits, even if they had the ration coupons to get it with.

In the 1950s, the government was trying to encourage women to leave the workforce and return to their homes, freeing up the jobs for me. It didn’t work, though, because taxes were rising at the same time, creating the need for two-income households.

Commercial TV, and food advertisements on it, began in 1955.

Larger grocery stores began to switch to self-service shops, where you wandered up and down the aisles to serve yourself (today’s model.)

In the 1960s, Indian, Chinese and Italian restaurants began to arrive. By the middle of the decade, every medium-sized town had a Chinese takeaway.

Some vegetables such as tomatoes became available during the winter, flown in from sunnier climes such as the Canary Islands. Frozen food appeared in stores.

In 1964, shops could set their own prices. Up until then, by law, food manufacturers had to print the price on each product, and it had to be sold for that. This was to protect small stores. They had objected vigorously to allowing larger stores to set their own, lower prices.

Kentucky Fried Chicken (KFC) arrived in the UK in 1965, opening its first outlet in Preston, Lancashire in May of that year.

In the 1970s, Delia Smith first appeared on TV.

In 1974, pre-sliced white bread started being sold in plastic bags: before then, it had been sold in waxed paper. McDonalds arrived in the UK in the same year.

By 1979, 40% of British homes had a freezer.

By the start of the 1980s, the shift was back on to women working outside the home. Microwaves arrived, hamburgers became popular and convenience foods became more important.

Under the government of the 1980s, people’s disposable incomes rose with the decline in taxes, allowing working-class people to afford more kinds of food and to grow their tastes, and to afford the healthier choice foods that the middle-class writers had been telling them to eat. Dramatically increased home ownership also meant that items such as fridges and freezers could become common.

Marks and Spencers was the first to sell fresh sandwiches in 1980. The first best seller was prawn mayonnaise (shrimp salad with mayonnaise.) Other stores soon followed suit.

In the same year, plastic milk bottles appeared.

By the end of the decade, the grocery stores were selling fresh dishes from the chiller ready to be heated at home. Pre-washed, bagged salads appeared at Marks and Spencers in the late 1980s.

In the 1990s, supermarkets sold prepared, quality food fresh and ready to heat or cook. As people had less time to cook, they actually got more interested in food and cooking as a leisure-time activity.

Supermarket chains began opening mini-versions of themselves in downtown cores in the early 1990s. The first opened in 1992 in Covent Garden in London, by Tesco, which they called “Tesco Metro.”

In the mid 1990s, large volume discount grocery stores, based on the American model, began to open. As disposable incomes began to shrink again with rising taxes, they became stores that everyone would shop at.

Produce available exploded, coming from all over the world.

By 1999, chilled prepared meals were more popular than frozen ones. Chilled meals made popular a wider range of more interesting, better quality prepared meals than was possible with frozen.

By 2000, all expenditures on food for a household, including both eating in and out, was only 16% of the average household’s spending.

In 2004, consumers in the UK spent 1.1 billion pounds sterling on chilled convenience foods.

Literature & Lore

“What is particularly striking about the revival of the British cheese industry is its journey from near extinction during the privations of World War II, when the Ministry of Food commanded all dairy production to abandon variety in pursuit of a single cheddar-style national cheese. Nationalization all but crushed the industry, with fewer than 100 independent British cheesemakers still in business by 1945, compared to more than 3,500 prior to World War I. Nigel White, secretary of the British Cheese Board, told the Star the industry continued to suffer through restrictive milk pricing policies well into the 1980s, when the government ‘gradually took its foot off the brakes. And when the British milk marketing board was abolished altogether in 1994, things really began to take off.’ The traditional cheeses were revived in depth and varieties far beyond the sharply aged cheddars… as timeworn recipes were dug out of libraries… and brought back to life. Simultaneously, a spirit of experimentation and innovation brought a panoramic range of new cheeses to the table.” — Mitch Potter. Cool Britannia rules the whey. Toronto, Canada: The Toronto Star. 9 October 2007. Page A3.

“I have no penny,” quoth Piers, “Pullets for to buy

No neither geese nor piglets, but two green [new] cheeses,

A few curds and cream and an oaten cake

And two loaves of beans and bran to bake for my little ones.

And besides I say by my soul I have no salt bacon,

Nor no little eggs, by Christ, collops for to make.

But I have parsley and leeks and many cabbages,

And besides a cow and a calf and a cart mare

To draw afield my dung the while the drought lasteth.

And by this livelihood we must live till lammas time [August].

And by that I hope to have harvest in my croft.

And then may I prepare the dinner as I dearly like.

All the poor people those peascods fatten.

Neans and baked apples they brought in their laps.

Shalots and chervils and ripe cherries many

And proffered pears these present… ” — Excerpt from “Piers Plowman.” (The Vision of William Concerning Piers Plowman). Shows the life of a peasant in England in the 1300s.

“Sing a song of War-time,

Soldiers marching by,

Crowds of people standing,

Waving them ‘Good-bye’.

When the crowds are over,

Home we go to tea,

Bread and margarine to eat,

War economy!” — Nina MacDonald, “Sing a Song of War Time”, in War and Nursery Rhymes (Routledge, 1918)

“Today in Iraq, American and British troops handed out food to hundreds of Iraqis. But to no surprise the Iraqis handed the British food back.” — Conan O’Brien, 2003.

“One cannot trust people whose cuisine is so bad. The only thing they have ever done for European agriculture is mad cow disease. After Finland, it is the country with the worst food.” — Jacques Chirac speaking of the UK to Vladimir Putin. 4 July 2005.

“Many a belief about traditional food turns out to be wrong once you examine the detail, he says. ‘It’s a myth that we boiled vegetables to death. Mrs Beeton says it takes half to three quarters of an hour to cook cabbage, but it was whole Savoy cabbages – that’s about right.’ ” — Ivan Day (food historian), quoted by Hattie, Ellis. Ancient recipes: Repast historic. London: Daily Telegraph. 30 December 2008.

Sources

[2] “But she [Lady Pamela Mountbatten] was 18 when the Queen married Prince Philip and was pleased with her first grown-up dress. She fondly remembers how women sent in their clothing coupons from all over Britain (rationing was still in force) so the Queen could afford a wedding gown.” — Hicks, India. A royal bridesmaid’s VERY surprising big day. London: Daily Mail. 8 January 2011.

Adams, Tim. Britain’s food decade. Manchester: The Guardian. 15 May 2011.

Battersby, Matilda. Chinese food ousts Indian as Britain’s favourite. London: The Independent. 13 October 2009.

Carpenter, Louise. Food and class: does what we eat reflect Britain’s social divide? Manchester, England: The Guardian. 13 March 2011.

Dafoe, Daniel. Tour through the Eastern Counties of England, 1724.

Derbyshire, David. ” Raise a glass to England’s sparkling wine industry”. Daily Telegraph, London. 5 May 2005.

Greenman, Ben. More Than London Broil: Rebecca Mead discusses England’s dubious culinary past. The New Yorker. 6 August 2001.

Jones, Richard. The New Look — And Taste — Of British Cuisine. In “The Virginia Quarterly Review”. Charlottesville, Virginia: The University of Virginia. Spring 2003.

Lamontagne, Jean-Claude. Les fromages britanniques, une courte info. Saveurs. May 1997.

McFarlane, Yvonne et al. The Dairy Book of British Food. London: Ebury Press, 1988.

Miller, Karyn. London: the best place on Earth to eat. Daily Telegraph. London. 27 February 2005.

Potter, Mitch. Cool Britannia rules the whey. Toronto, Canada: The Toronto Star. 9 October 2007. Page A3.

Wainright, Martin. Chips are down for Britain’s Classic dishes. Manchester, England: The Guardian. Monday, 24 July 2006.

Ward, Paul. Margarine and Knitting: British Women, Britishness and the First World War. Presented at ‘Frontlines: Gender, Identity and War’ conference. Monash University, Melbourne, Australia. July 2002.

References

| ↑1 | Wallop, Harry. Cox apple toppled by the gala. London: Daily Telegraph. 13 March 2011. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | A nice cup of tea. In: Exploring English Food and Culture. The British Council. Module 4.7. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/exploring-english-food-and-culture/1/steps/1185275 |

| ↑3 | ”Tea bags were invented in America in the early twentieth century, but sales only really took off in Britain in the 1970s.” — UK Tea and Infusions Association. Modern Tea Drinking. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.tea.co.uk/history-of-tea |

| ↑4 | A nice cup of tea. In: Exploring English Food and Culture. The British Council. Module 4.7. Accessed July 2021 at https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/exploring-english-food-and-culture/1/steps/1185275 |