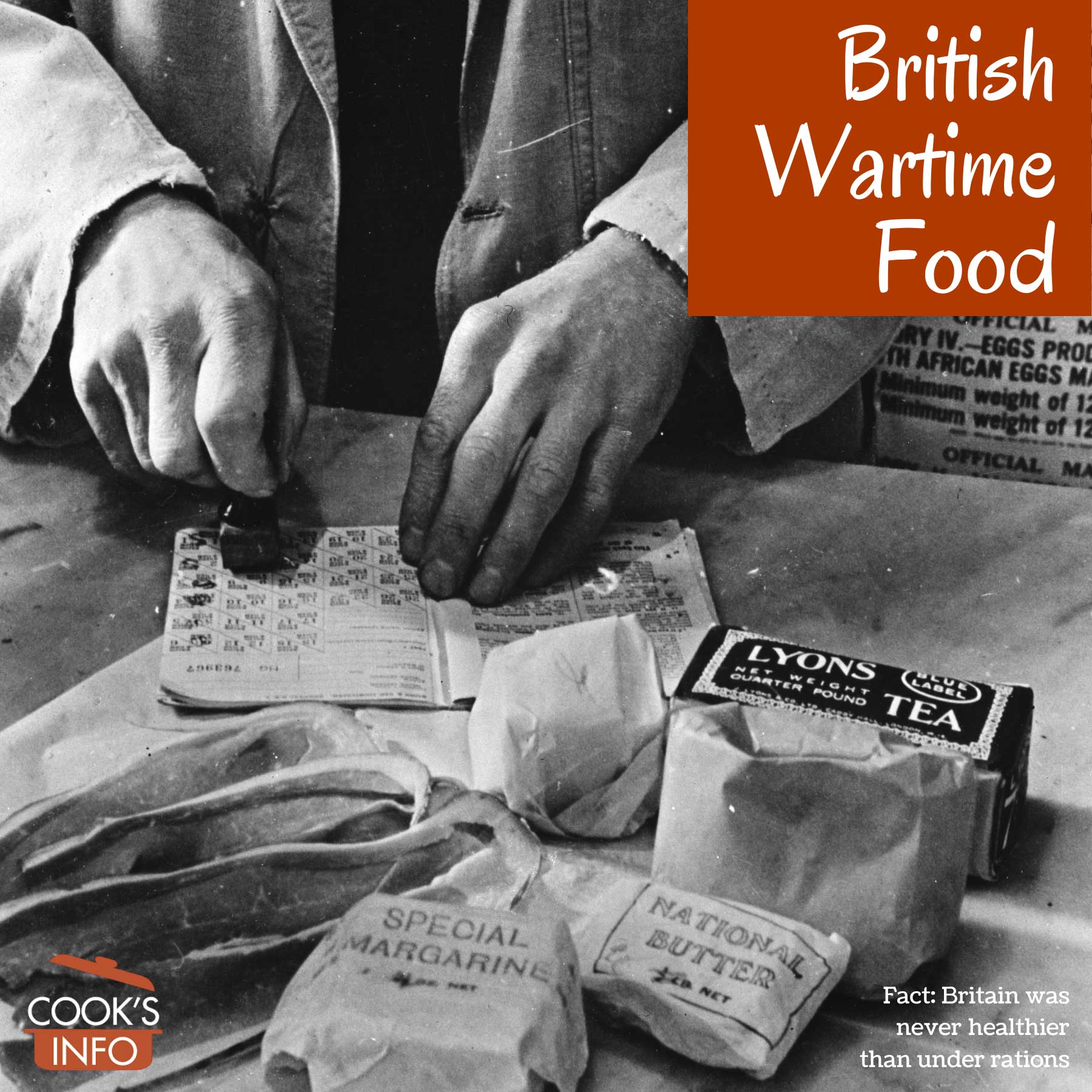

British shopkeeper cancelling coupons. April 1943. United States Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division.

For the Second World War, the United Kingdom leveraged knowledge and experience from the First World War to feed its population.

During the First World War (1914 to 1918), queues for food became dangerously long. Consequently, a Ministry of Food was created in 1916 to help with the home front food situation. Rationing was introduced starting with sugar in December 1917, then with meat and butter in February 1918. The government congratulated itself on its measures, and the Ministry of Food was dissolved on 31 March 1921.

In truth, though, it wasn’t a great success: food prices rose by 130%, and the ration coupons were often useless, as the supply of items just wasn’t there to meet even that coupon-limited demand.

The U.K. would do better during the Second World War (1939 to 1945.) The government was always able to honour all ration coupons, and food prices during the war rose by only 20%. The British population emerged healthier than it had ever been before, and families had been educated in putting nutritional, frugal meals on their tables. In many ways, it was home economics that would win the war.

See also: Bread Rationing Ends in the United Kingdom, Start of Second World War 1939, Sweet Rationing ends in the United Kingdom, Tea rationing ends in the United Kingdom, Marguerite Patten, New Zealand Wartime Food

- 1 Leadup to the Second World War

- 2 Ministry of Food

- 3 Reliance on allies for food supplies

- 4 Ration Booklets: Coupons

- 5 Ration Booklets: Points

- 6 Shopping for Food In World War Two Britain

- 7 Dig for Victory

- 8 Women’s Land Army

- 9 Canning and Preserves

- 10 The Root Vegetable Campaigns

- 11 Special British Wartime Food Products

- 12 Meat in Britain during World War Two

- 13 Pig and chicken clubs

- 14 Fats

- 15 Restaurants

- 16 Population Health

- 17 Wartime Kitchens in Britain

- 18 The Great Onion Scarcity

- 19 Rationing allowances

- 20 Christmas ration bonuses

- 21 Rationing Timeline

- 22 Literature & Lore

- 23 Sources

- 24 BBC WW2 People’s War Memories Archives

Leadup to the Second World War

In the 1930s, before the outbreak of the Second World War, the population of the United Kingdom was somewhere between 46 million and 52 million.

Britain imported 70% of its food; this required 20 million tons of shipping a year. 50% of meat was imported, 70% of cheese and sugar, 80% of fruits, 70% of cereals and fats, 91% of butter. Of this, ⅙th of meat imports, ¼ of butter imports and ½ of cheese imports came from New Zealand alone, a long way away by vulnerable shipping lanes.

The Axis powers knew this, and drew up strategies to starve the British population into submission by cutting off those food supply lines.

The British government began planning for wartime rationing in 1936. Should war occur again, this time they hoped to be better prepared based on their experiences the last time around. A Food (Defence Plans) Department was set up as part of the Board of Trade to do the project planning. Ration booklets were printed up in 1938, ready to go.

Ministry of Food

Britain declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939.

Lord Woolton, Minister of Food, serves up food to diners at a mobile field kitchen in Sussex 1941.

On the 4th September 1939, the Ministry of Food was reconstituted, with William Morrison as the Minister.

On 3 April 1940, Neville Chamberlain replaced Morrison with Frederick Marquis, Baron Woolton. Marquis (his real last name) had been a former social worker and former managing director of the Lewis store chain in Northern England. He had proven experience in communicating with consumers, and had been awarded a peerage in 1939 before the war for his contributions to British industry. He had not been involved in politics or government previously. He would remain Minister of Food until December 1943, at which time Churchill transferred him to the Ministry of Reconstruction to start planning to rebuild Britain after the war.

Woolton decided that it wasn’t enough to just ration food or limit what people ate; he set the Ministry the goals of treating the British public as consumers, and explaining nutrition to them in simple terms so that they could get the most nutrition out of the available food despite the rations.

Ministry of Food advice exhibiton, London, 1943.

Previously, before the war, the British government had luckily been influenced by the thinking of home economists. Consequently, it was widely accepted by government in the UK that there was a strong link between diet, and a healthy population. Woolton’s chief scientific advisor was Jack Drummond, who worked closely with Wilson Jameson, British Chief Medical Officer from 1940 to 1950.

Their methods of communicating would prove to be effective: by the end of the war, housewives had become very educated in nutritional vocabulary. The Ministry issued many cooking leaflets, often dedicated to specific topics such as the magic of carrots. The language used was practical, and realistic for the time — in listing ingredients for suggested recipes, the government leaflets would often say beside an ingredient such as butter: “if possible.” Cooking demonstrations by women such as Marguerite Patten were held in many stores, including Harrods. Educational short movies on cooking were made for showing at cinemas; BBC Radio ran a morning radio programme called “Kitchen Front”, broadcast from studios in Oxford Street, London, hosted by Stuart Petre Brodie and featuring guests such as Marguerite.

15,000 people eventually worked for the Ministry of Food. There were 18 Food Officers in Great Britain, and 1 in Northern Ireland, 1,500 Food Control Committees (with consumer and retailer representatives on them), and 1,300 Local Food Offices, who distributed ration books and licenced shopkeepers to handle them.

The Ministry of Food went so far as to regulate how grocers got the food that they sold to their customers. They were told to get their supplies from the nearest wholesaler or maker of the item, in order to reduce distribution costs and save petrol, rather than shopping around and ordering in items from around the country. By 1942, this applied to items such as margarine, bread, flour, cakes, biscuits, and bacon.

In June 1942, Lord Woolton made the following report in the House of Lords:

Lord Woolton: We have told traders who buy margarine that they must take it, not from where they want to get it, but from the nearest factory that is making it. We have prescribed the places from which the retailer can get his goods because we have got what is, substantially, a standard margarine all over the country, and it is just as good from one place as from another. We called together the bread people. We have arranged that the deliveries of bread shall be zoned, so that people do not go crossing unnecessarily the routes of others. We have been to the millers. We have told the millers that instead of delivering flour as they have been accustomed, according to the places where they had their clients, flour must in future be delivered from the mill that is nearest to the bakery.

I recently have come to an agreement — the noble Earl, Lord De La Warr, suggested this method, which is one we are practising — with the cake and biscuit people. I asked them to meet me. I told them we no longer could afford, as I have told all these people, the amount of transport and man-power involved in this extravagant system of distribution, and that questions of their own good will just had to go by the board for the period of the war. The result of that is that 300,000 retailers have been reshuffled among the cake and biscuit manufacturers in this country so that they now draw their supplies from the places which are nearest. We have saved 12,000,000 ton-miles of transport, a matter of 40 per cent. of the transport of these trades. We have done the same thing with the bacon trade. Seventy-four per cent of the bacon that is in the shops in this country now travels less than twenty-five miles in order to get there instead of going all over the country. We have done the same with sugar, where we have saved 10,000,000 ton-miles as a result.

By these processes—and this will become obvious in a few weeks — we are restricting the choice of the public. They will no longer be able to say that they must have the product of the firm X because they prefer it to the product of the firm Y. Sweets we have restricted into various areas, only one firm supplying the same commodity in that district. We have saved 10,000,000 ton-miles as a result, and 500,000 gallons of petrol. If I may mention beer, we are going to save 1,128,000 gallons of petrol next year, as compared with 1939, as a result of the reorganization of deliveries in the beer trade. This year we are going to determine where tomatoes shall go to. I hope that plan is going to receive the support of the market gardeners and the agricultural interests generally, because this certainly is true, that whilst your Lordships may on occasion urge me to take a more vigorous line, I do not always find when I have taken that vigorous line that I have got the unanimous support of the agricultural interests behind me. I made a conscientious effort, supported by the voluntary services of some very good citizens in this country, to deal with carrots and onions, but I do not think it met with a great deal of approval in spite of the effort and knowledge which went into it.

One more thing will be announced tomorrow. I am trying to get some orderly arrangement whereby retailers will only be allowed to draw their goods from wholesalers in certain areas. This means some restriction on the free choice of the retailer, but the restriction mainly is concerned with the goods that are already goods coming under control of the Minister of Food and in respect of which we prescribe prices. That scheme, which will divide the country up into a number of sectors and which will prevent all that overlapping that takes place in transport, will save a great deal of money, a great deal of labour — and that is more important than money in these days — and it will save a great deal of petrol.” [1]Frederick Marquis, Lord Woolton, speaking in the House of Lords. FOODSTUFFS: COST OF DISTRIBUTION. HL Deb 03 June 1942 vol 123 page 103 – 105.

The Ministry of Food also created secret food depot warehouses throughout the country in which it stockpiled food in the event of invasion. This was unknown to the wider population.

Reliance on allies for food supplies

A food commodities report from mid-1943 shows the reliance of the wartime United Kingdom upon the anglosphere to feed itself:

“BACON: This section maintained its steady features with adequate releases made for the week’s requirements. Consumer demand keeps on full ration basis. Category A permits were mostly supplied with Canadian Wiltshires, middles, fores, and hams. Category F had moderate allotments of American smoked hams.

LARD: American refined sorts continued reserved for the domestic trade. Compound fats were provided for large buyers and trade users, and allowances were well taken up.

CHEESE: Distribution was in progress in connection to-day with the new period beginning today. Wholesalers were handling New Zealand, United States, and Canadian makes, while Cheshire cheese appeared in larger proportion of deliveries with good acceptance.

BUTTER: Position shows firmness, with a new issue at the week-end consisting mostly of Australian meeting brisk demand for allowances. The full demand for margarine continued amply provided for.

EGGS: The twenty-fourth allocation has commenced and will probably continue over two weeks, decreased production causing slower deliveries. Two eggs per book are expected during August for ordinary consumers. Dried eggs were selling more freely, and one packet per book every four weeks will be the basis of distribution until the end of the year.” — Provisions. Liverpool, England: Liverpool Daily Post. Monday, 26 July 1943. page 4, col. 6.

Ration Booklets: Coupons

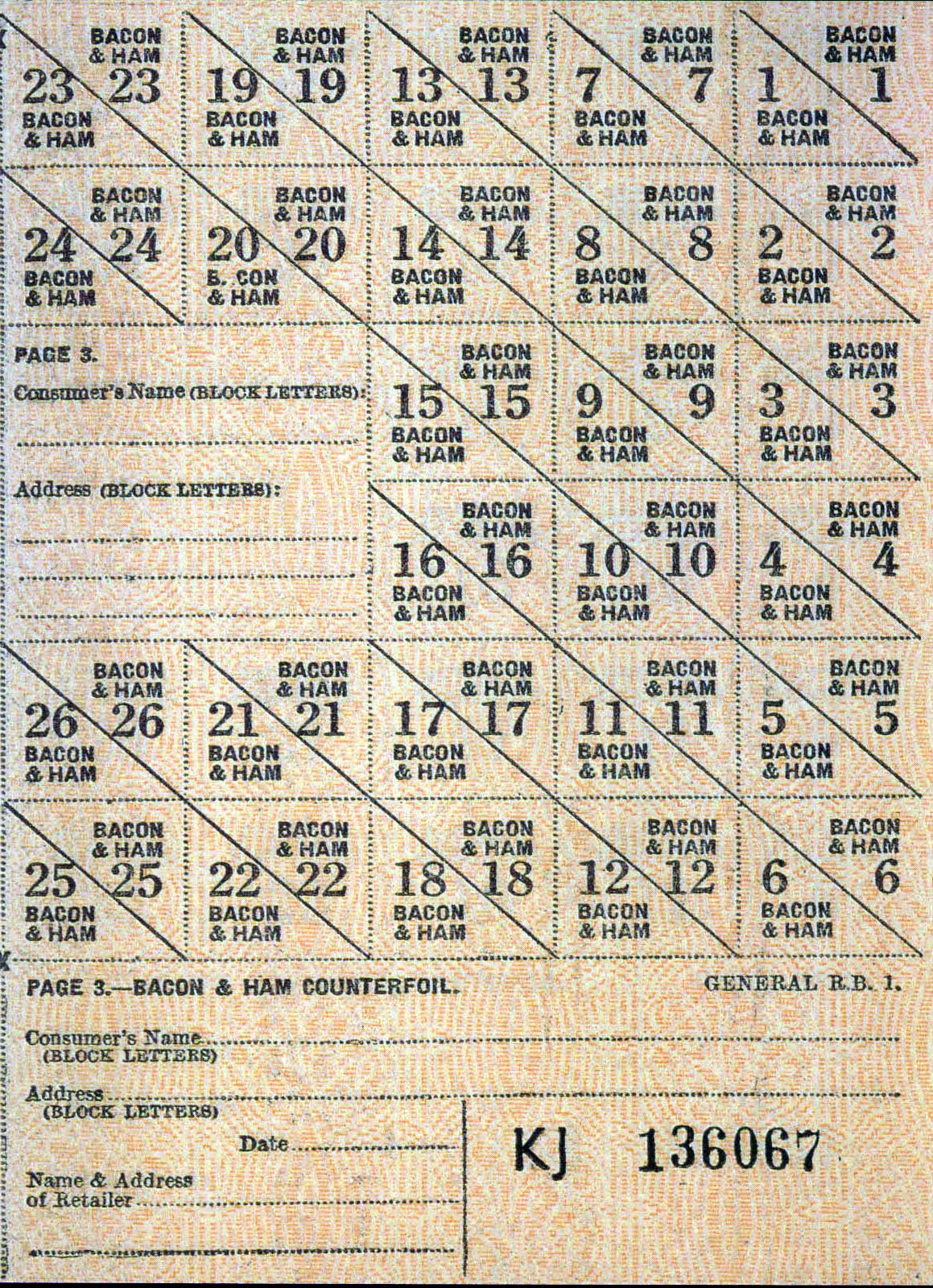

British WW2 ration coupons for bacon and ham

The already-printed ration booklets were issued to the public on 8 September 1939, 5 days after war was declared.

They were not actually used until four months later, however. Bringing rationing into effect was postponed several times owing to a virulent campaign in the press led by the Daily Express newspaper, which branded rationing an unnecessary folly and called it government interference with civil liberties. The government finally overcame political resistance and rationing came into effect on 8 January 1940.

It’s important to note that the food coupons in ration booklets didn’t entitle you to, say, butter, for free. Instead, they entitled you to purchase a certain amount of butter — you still had to come up with the money.

A ration book was issued to each person and each child. The public went to their local designated Ministry of Food offices to collect their ration books. A responsible person in the household could pick up and sign for the ration booklets for everyone in the household. New ration books were issued about once a year. To replace a lost booklet, you had to sign a declaration, and pay a 1 shilling fee.

You had to register at a store that you wished to use the coupons at, and could only use them there. There was no shopping around for those items.

At first, you had to use the coupons during the week indicated for those particular coupons being valid. Later, you could save them up a bit: bacon/ham for two weeks, other items for 4 weeks.

There actually was some flexibility in the system for special dietary needs: special ration books were issued for vegetarians, for those with religious dietary restrictions (Muslim and Jewish), people with special health needs, those engaged in hard physical labour, people from poorer backgrounds, etc. Vegetarians, Jews and Muslims, for instance, were allowed to use their ham or bacon allowance on cheese instead. Jews could get kosher meat.

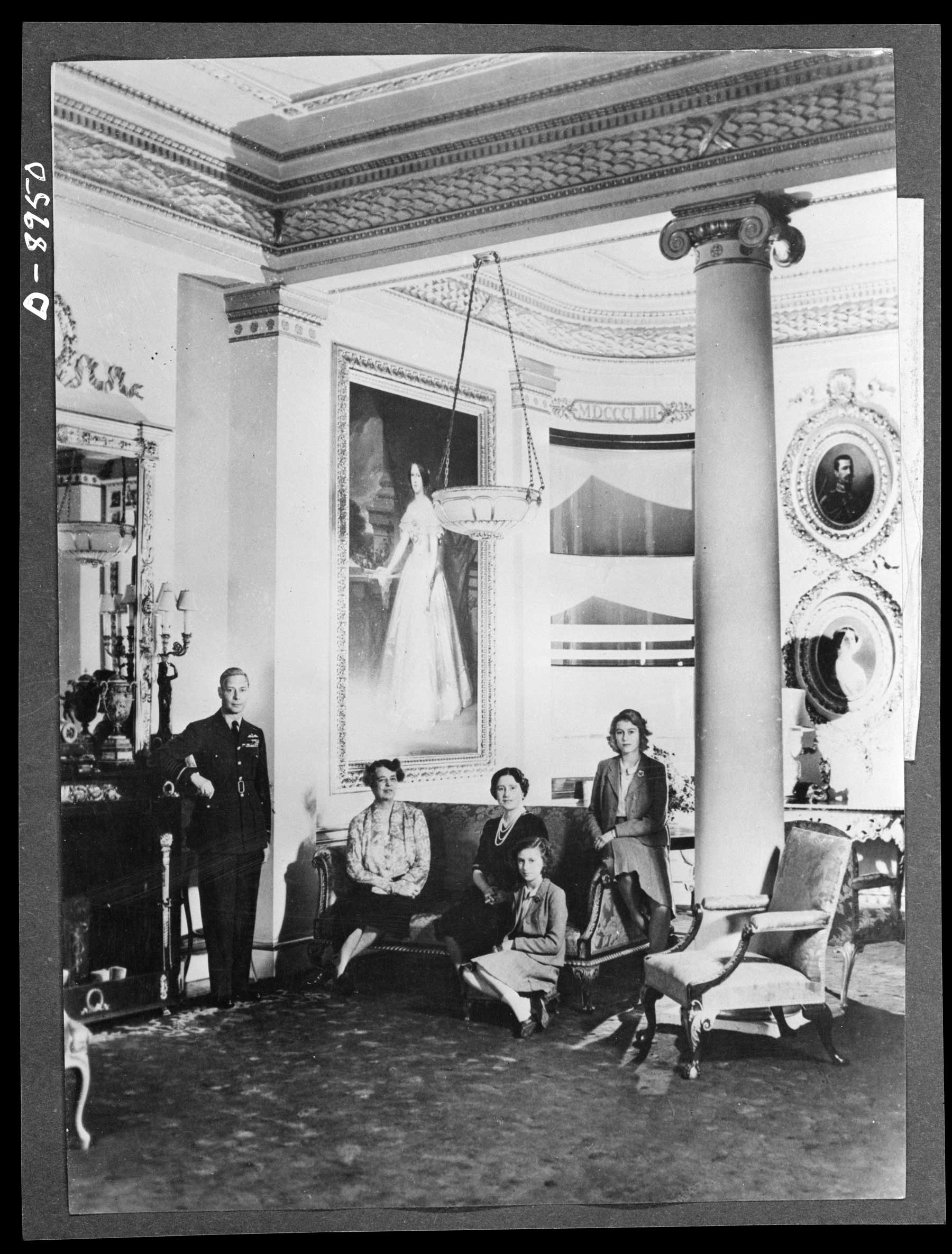

Rationing meant that no matter how rich you were, the food available was equally shared at fair prices. Rations applied to the Royal Family as well — even they were issued ration books, and had to register at merchants to use them. In 1944, Queen Mary was registered at Hall & Sons at 21 Buckingham Palace Road for meat, and at Warren Brothers at 32 Buckingham Palace Road for eggs, fats, cheese, bacon and sugar. [2]The Ministry of Food Exhibition photos: “Ration Book Inside.” Posted by Imperial War Museum 17 December 2009 at http://www.flickr.com/photos/imperial-war-museum/4193034670/in/set-72157622856066225

In 1942, when Eleanor Roosevelt stayed at Buckingham Palace, she reported on the rationing of food at dinner there (and noted that hot bath water was rationed as well.)

Eleanor Roosevelt at Buckingham Palace, 1942. Left to right: the King, Eleanor Roosevelt, the Queen, Princess Margaret, Princess Elizabeth. United States Office Of War Information.

An important functional principle was that, unlike during the First World War, the government applied rationing only to items that it could be sure of people being able to get always. The goal was to ensure that the consumer had confidence that their ration entitlement would always be honoured. A ration coupon was your guarantee that you would get your share of something, however small the shares were. Rationing wasn’t applied to seasonal items — say, summer fruit such as berries, as the government couldn’t guarantee, clearly, their year-round supply.

Notable items that were never rationed included salt, and coffee: Brits weren’t big coffee drinkers at the time so supplies weren’t likely to run out. Other items such as lemons and bananas weren’t rationed, either — because they simply disappeared from Britain for the entire war, and again, the goal of rationing was to guarantee a supply of something to consumers. Some people who grew up during the war didn’t see their first banana until they were 10 or 12 years old.

Bread was unrationed during the war, and then ironically, rationed after it. [3]Bread was never rationed in Britain during the war, though ironically it was for a short period after the war, from 21 July 1946 to July 1948. Some feel that the reason Prime Minister Attlee’s government introduced bread rationing was more political than out of actual necessity. Britain wanted two things from America: (a) That America should take over feeding refugees in the British occupied zone of Germany; (b) reconstruction loans and Marshall Plan aid. To this end, Britain needed, frankly, to look needy, even though it had a guaranteed wheat supply from Canada. Bread rationing ended in 1948 shortly after a signed and sealed agreement on Marshall Plan aid was safely in British hands. The complete story is covered by Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska in her “Bread Rationing in Britain, July 1946 – July 1948” in the journal “Twentieth Century British History” (Vol 4, No 1 1993. pp. 57 – 85).

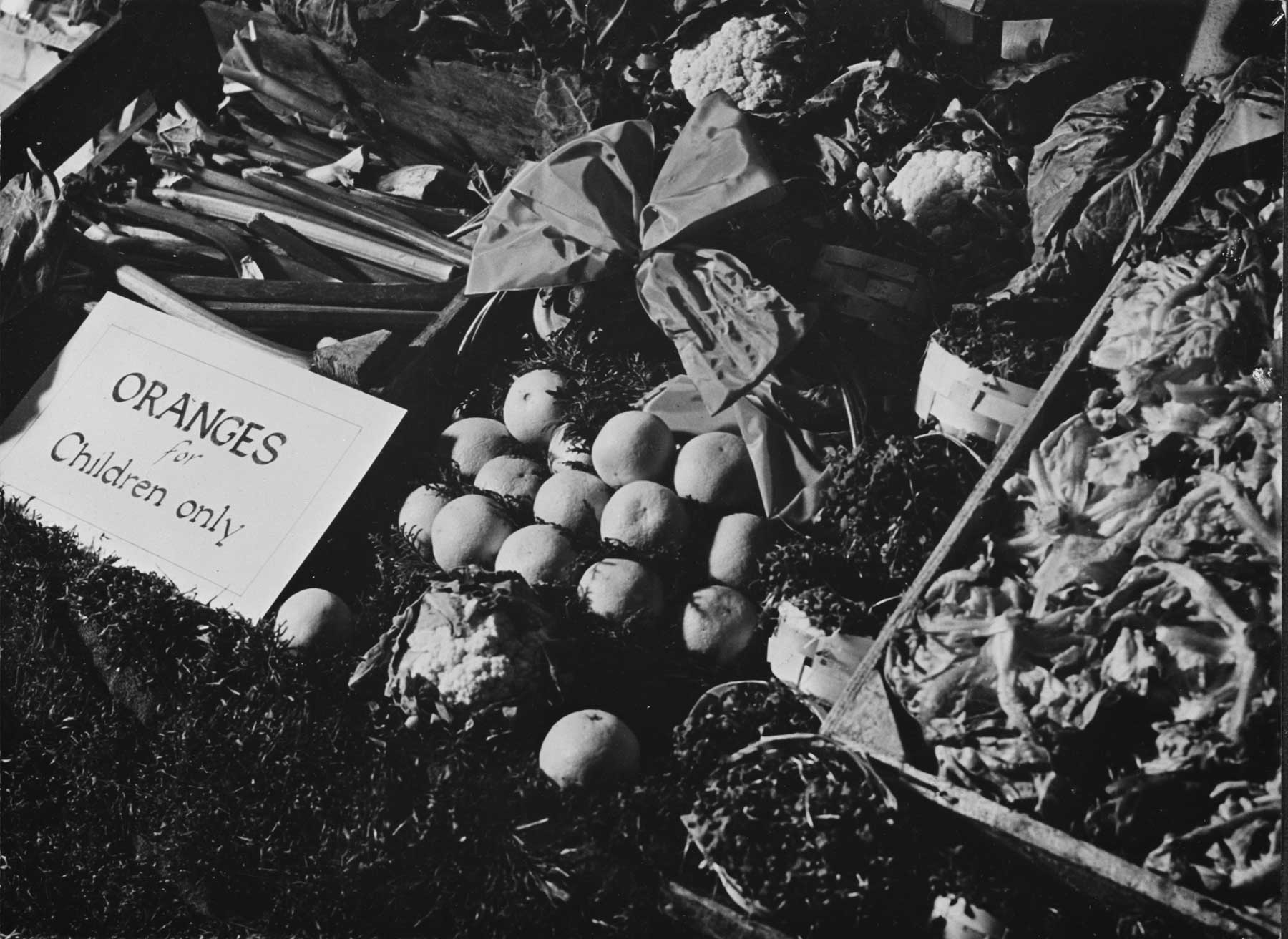

Fresh oranges got through occasionally from America — but consumption of them was restricted to children only.

Oranges on restricted sale for children only. April 1943. US Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division.

Ration Booklets: Points

Points rationing was introduced 1 December 1941 via a separate pink ration book. It ran in conjunction with regular coupon rationing, but was more flexible than coupon rationing.

A butter coupon would entitle you to purchase x amount of butter that week. But if you didn’t use it on butter, that was that: you couldn’t use it on anything else, and you couldn’t carry it forward; the points were valid only for that four week period.

The points rations gave shoppers greater choice than the ration coupons did, putting them more in control of their shopping. You got a certain number of points to use on any of the items, in any combination you wished, that were covered under points rations. (Again, you still had to cough up the cash for the actual purchase.) And, you could do the purchases anywhere, not just at the grocer you registered at for the coupon usage.

The first items to go on points rationing were tinned meats, tinned fish and tinned beans; later, points rationing was applied to most tinned goods, dried fruits, cereals, legumes, biscuits, etc.

When points rationing was first introduced, everyone had 16 points per every four weeks. Later that was raised to 24 points, then on 27 May 1945 reduced downward again, to 20 points.

The Ministry of Food could adjust upwards or downwards the number of points that a food item would cost, depending on the supply of it at the time in the nation’s food chain. Housewives would watch the newspapers to monitor news on the “Changes in Points Value” columns, to see if anything they wanted had become cheaper (or more expensive) in points.

For instance, upon the introduction of points rationing, a one-pound tin of canned salmon or of canned sausagemeat from the U.S. originally required 16 points. People weren’t trying the American canned sausagemeat, so the Ministry of Food raised the points requirement for the salmon to 24 points, and reduced the points required for the canned sausage meat to 8 points to encourage people to try it. The “sausage meat” in question was otherwise known as Spam; the British public eventually came round to it.

Shopping for Food In World War Two Britain

Once the ration booklets were received for that year, you would take them and register them at the grocery stores you intended to use them at.

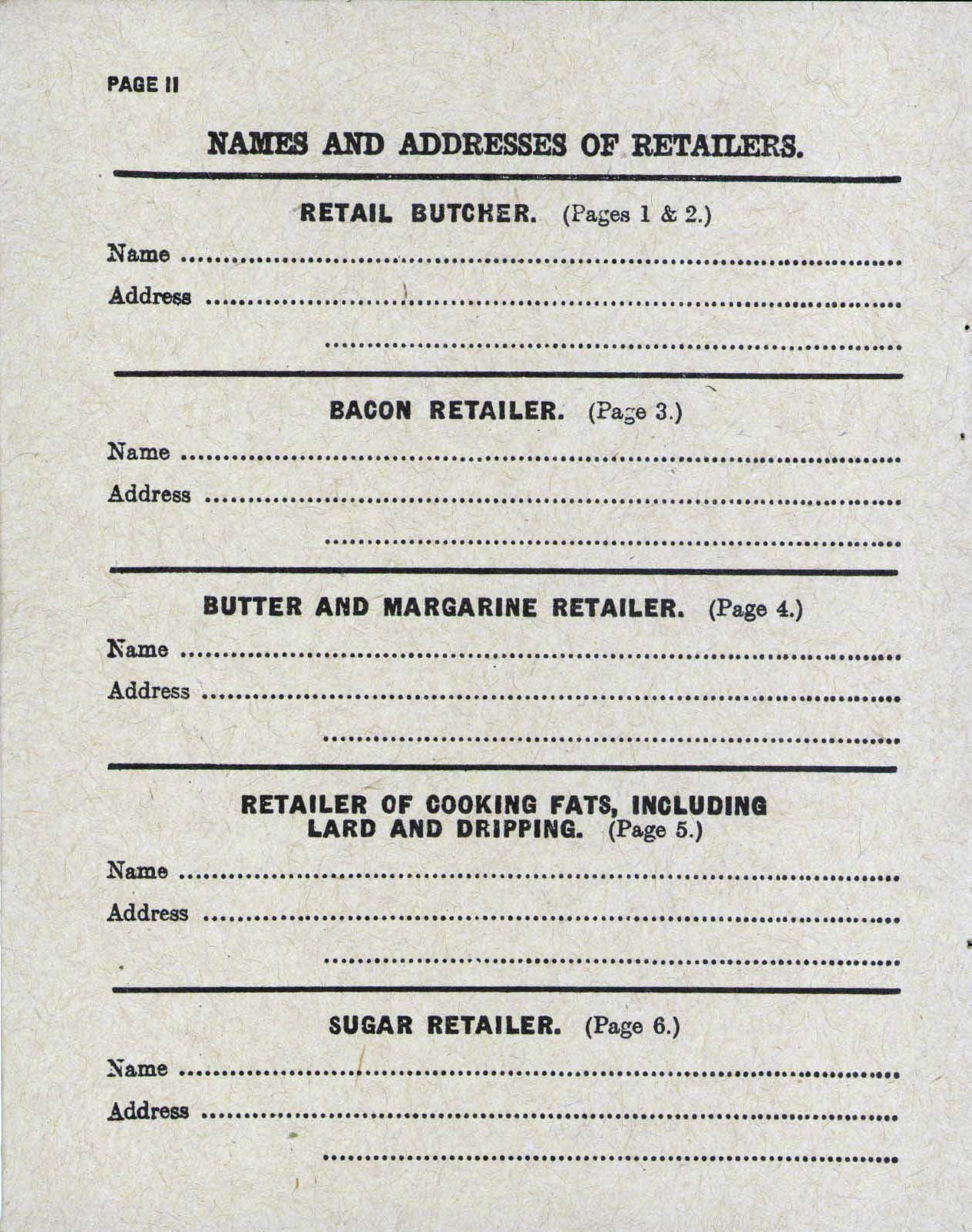

British WW2 ration booklet stores registration

Note the plural, stores. This was before the days of supermarkets. You went to different stores for different items: the greengrocer, the butcher, the baker, the fishmonger, etc. You would register at one store for meat, another for dry goods, etc. Sometimes, a grocer would sell more than one of the rationed items, and you could register for purchasing both there, if you wished. Shoppers would debate whether it was best to spread their registration slots around to different stores, in the hopes of spotting more items suddenly appearing for sale, or to concentrate them all at one store, in hopes of gaining favoured customer status for special items held back under the shop counter.

The exception was tea ration coupons: you could use them at any store you wished. You did not need to register them. Note that the tea then would have been loose tea, not tea bags, as tea bags hadn’t caught on at the time. And as for using it, the Ministry of Food advised “one spoonful for each person and none for the pot.”

New ration books were issued about once a year. That was a good time to change who you were registered with, if you wanted to. You could change at other times, if you wished, but it was tricky to do so without offending a shop keeper that you might later need to return to or want favours from later.

Shopkeepers got just enough food for the customers they had registered with them. Stores were encouraged to form Traders’ Mutual Aid Pacts, to allow each other to temporarily take over looking after a store’s registered customers if that store were bombed out.

A family member could go to the store with all the ration books for that family (in practice, it was usually the mother.) You showed the shop keeper your coupons that allowed you to make the purchases. If they were regular ration coupons, the shop keeper then cancelled them in the booklet with a stamp. If you were using points coupons, they were cut out. Then, you passed over the money for that purchase.

If you had used up all the coupons for an item for that week, or points for that four week period, then that was that until the next time period. No amount of money could get you the items in question.

Even if you didn’t want your rations or need all of a particular rationed item that you were entitled to, most people bought them anyway, and sold them, usually at cost, or traded them, to friends or neighbours who would want them.

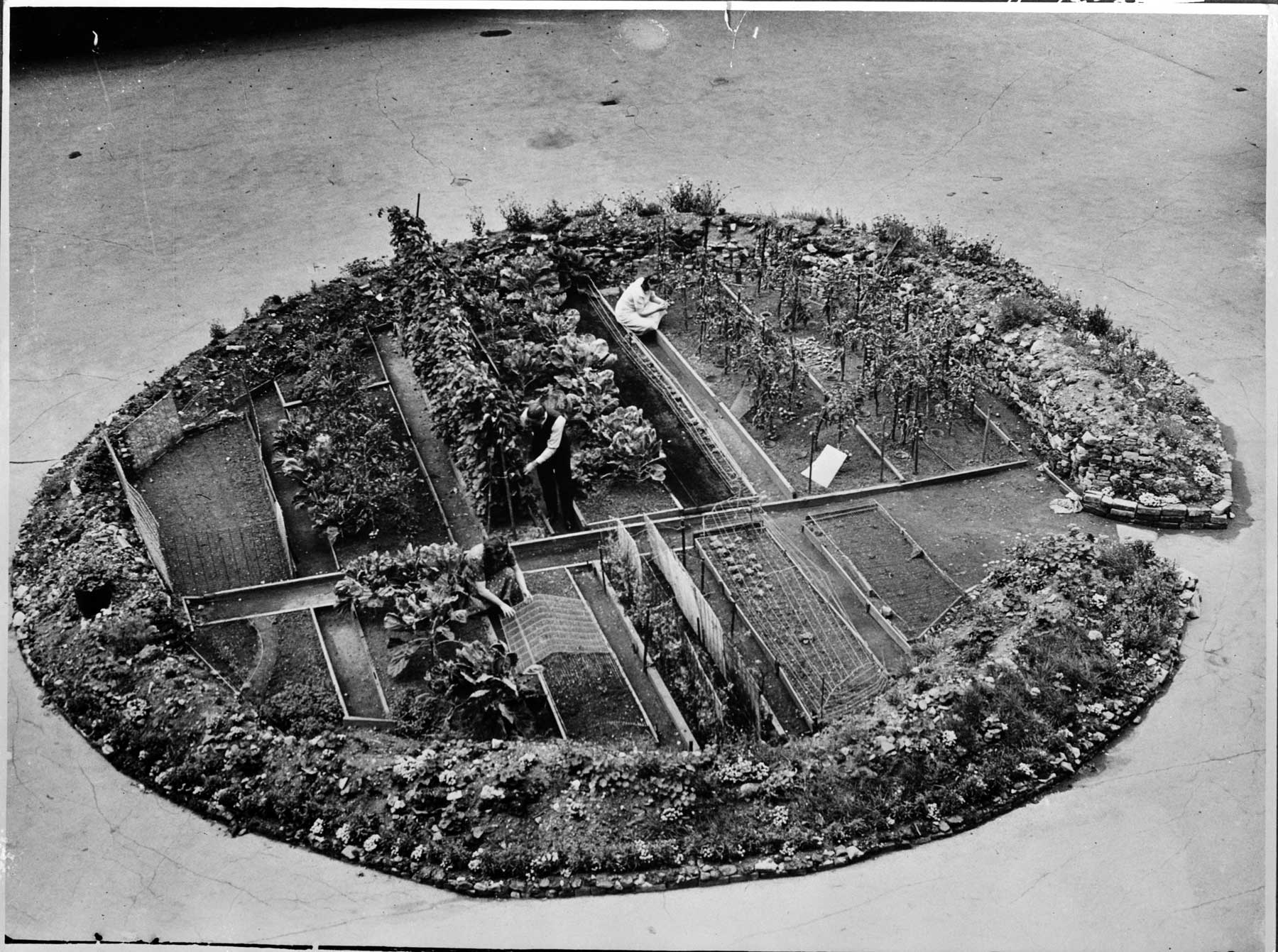

Dig for Victory

Display in Kew Gardens, London. William / geograph.org.uk / 2013 / CC BY-SA 2.0

The Ministry of Food launched its ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign in October 1939, one month after war broke out. The campaign was led by an agricultural economist, Professor John Raeburn, who was recruited to the Ministry of Food in 1939, and who would run the campaign until the end of the war.

The campaign encouraged people to transform their front and back gardens into vegetable plots. The goal was to replace imported food, thus freeing up shipping space for more valuable war materials, and to make up for food that was sunk in transit. By the end of 1940, 728,000 tons of food making its way to Britain had been lost, sunk by German submarine activity.

Dig for victory poster

“This is a food war,” said Lord Woolton, Minister of Food, in 1941. “Every extra row of vegetables in allotments saves shipping… the battle on the kitchen front cannot be won without help from the kitchen garden.”

In 1941, the Americans sent nine tons of vegetable seeds over through the British War Relief Society for the British public to use in their home gardens. Most vegetables were not rationed; cauliflower became a staple vegetable at meals.

Granted, keeping vegetable gardens and animals was easier for people living outside the big cities, so in response, the Ministry requisitioned green spaces in cities — even some parks such as the Royal Park, Kensington Gardens — and divvied the land out to households in parcels known as “allotments”, a small space where you could go and set up your own vegetable patch (and hope that a stray bomb didn’t find its way there right at the start of harvest season.)

March 1943. Victory garden planted in a bomb crater, close to Westminster Cathedral in London.

Commercial fertilizers for gardens had of course disappeared at the start of the war, so whenever a delivery cart and horse, or a police horse, happened to pass by a house, mothers would send many a humiliated child out to the road with a bucket and shovel in the hopes that the passing horse had left a calling card in the form of some manure.

During the war, daylight savings was put ahead by two hours every year in March, to allow more daylight hours for farming, and gardening after work.

Overall, the campaign was a massive success: by 1943, it was estimated that home gardens were producing over one million tons of produce, and by 1945, around 75% of food consumed in Britain was produced in Britain.

The campaign was still kept up after the war in order to free up food to feed the starving populations of Europe.

Women’s Land Army

British Women’s Land Army helping to harvest hay. United States. Office of War Information. 1943.

A Women’s Land Army (WLA) had been created in the First World War to help farmers and market gardeners by drawing on women to replace the male agricultural workers who had gone into the armed forces. The goal was to ensure that home front agricultural food production was maintained. It was disbanded at the end of that war.

The Land Army was reconstituted in June of 1939, 3 months before the Second World War broke out, by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, with Lady Denman being the honorary head. It was volunteer at first; some women worked part-time, seasonally as needed. Later, conscription of girls over 16 was used to bolster the ranks.

A third of the women came from cities; the other two-thirds came from the countryside.

The work was 48 hours a week in the winter; 50 to 54 hours a week in the summer. They got a uniform consisting of a green tie and jumper (aka pullover sweater), and a brown hat, and extra rations, but were paid about 20% less than the male workers they replaced.

Some lived with the farming families; on larger farms, some were given accommodation in special cabins built for them. Some were placed near to where they lived, enabling them to return home each day.

The women were often moved from farm to farm, depending on where they were needed when.

By 1944, there were over 80,000 women in the British Women’s Land Army.

The Land Army was disbanded on 21 October 1950.

Women who participated felt that they never really got much recognition; a ceremony was finally held in June 2008 in which then Prime Minister Gordon Brown presented badges to some of the veterans still living at the time.

See also: Archive of Land Girls’ Memories on BBC (link valid as of 2021)

Canning and Preserves

These were the days before refrigeration and freezing was common in household kitchens (and not just the U.K. — the refrigerator revolution did not sweep the U.S. until the late 1940s), so housewives still knew and used preservation techniques such as canning (aka bottling in the U.K.). The Ministry of Food educated people with leaflets, radio programmes and community demonstrations on the latest and greatest food preserving techniques to ensure that no food went to waste.

Eggs could be kept fresher for a bit longer by rubbing them with lard to seal the pores, or for longer periods, by storing them in crocks under water with isinglass or waterglass mixed in, or by turning them into pickled eggs. (See: Preserving eggs).

Canadian Women’s Institutes supported their sister British Women’s Institutes, by donating to them useful tools such as canning machines, etc, which could be shared out.

Preserving of fruits and vegetables was largely done in a brand of Mason jars known as Kilner: glass jars with glass lids with a bail-type closure system on them. You put a rubber ring around the neck of each jar before sealing it. You replaced the rubber rings after each use.

Even if you grew your own fruit, making jams and other preserves from it was tricky as sugar was rationed and you weren’t likely to be able to get enough sugar, unless you had some food item you could swap with someone else for their sugar. Many people started saving up their sugar rations right at the start of the summer to help with canning time. (Some years, during the summer, the Ministry of Food was able to double the sugar rations to encourage home preserving.)

The Women’s Institute, a Canadian idea that had expanded to the UK by 1915, received special sugar allowances to aid in its work in bolstering the food supply:

“The Ministry of Food allowed WI preserving centres a supply outside of the members’ personal rations to preserve the fruit, but obviously they expected very rigorous control. The amount of sugar was carefully calculated for each recipe to provide the best keeping qualities with the least sugar… Records were kept of how much sugar was used in each batch [of jam], and each batch was weighed and recorded. Sugar was, of course, in short supply and every grain had to be accounted for. ” — Ruth Goodman. In: Ginn, Peter et al. Wartime Farm. London, England: Mitchell Beazley. 2012. Page 130.

The Ministry of Food also advised people on how to preserve meat through curing and other means. Pork chops or lamb chops could be preserved for up to six weeks by first cooking them, and then putting them in a crock completely covered with fat.

The Root Vegetable Campaigns

Dr Carrot

Carrots were particularly promoted to the population, as there was no shortage of them, and they were deemed very healthy.

The Ministry of Food suggested Carrolade (a homemade juice blend from mixed carrot and Swede juices), carrot jam, curried carrots, etc.

For use in the Ministry’s promotional efforts, a carrot family was invented for them by a Disney cartoonist on the other side of the Atlantic, a Hank Porter: members of the family included Carroty George, Clara Carrot, and Dr Carrot (the Ministry of Food transformed him into Pop Carrot, as they already had their own Dr Carrot figure.) The drawings were wire-photoed to London, courtesy of RCA. The characters were used in newspaper campaigns, recipe booklets, posters and flyers.

Marguerite Patten later said she remembered that you wouldn’t peel carrots; to reduce wastage, you’d wash them instead and leave the skin on, and cut the tops off as thinly as you possibly could.

The Ministry of Food also created a Potato Pete character.

Potato Pete

The character acquired his own song, recorded by a woman named Betty Driver, later to become famous for portraying Betty Williams in Coronation Street, who in turn would become famous for her potato dish, Lancashire Hotpot.

Those who have the will to win,

Cook potatoes in their skin,

Knowing that the sight of peelings,

Deeply hurts Lord Woolton’s feelings.

The Ministry recommended scrubbing potatoes clean instead of peeling them, as peeling caused wastage, however small.

One of the most famous dishes invented during the war was Woolton Pie, for the purpose of promoting root vegetables in general. It was created by Francois Latry (1919-1942), the chef at the Savoy Hotel in London, and named in honour of the Minister of Food himself. The pie consists of carrots, turnips, parsnips and potatoes simmered in an oatmeal stock, then turned into a baking dish, topped with a crust of dough, or mashed potato, and baked. Sadly, despite all the promotion that the recipe was launched with, the dish never really took off in popularity amongst the public.

Special British Wartime Food Products

Powdered eggs and dried milks. Paul Hudson / flickr / 2015 / CC BY 2.0

The Ministry of Food actually invented several food products, and legislated their production to substitute for other goods.

All were a success in terms of keeping the population healthy and fed. Sadly, not all were a success in terms of endearing themselves to the tastebuds of the population.

White flour was banned for the most part for household use [Ed: it was still allowed commercially in the production of some biscuits, etc.], being replaced by a National Flour, with “wheatmeal” being the official name invented for it. While not quite whole wheat flour (in order to be a bit of a compromise), it left all the bran in it. It was greyish in colour. Some women in desperation would sieve it through their nylon stockings to get white flour; if you kept chickens, the bran sieved out could go to make a ration-free mash for the chickens.

Bakers were obliged to use the National Flour to make only one type of bread, which was called the National Loaf. Nutritionists praised the composition of the bread (and fought for it to be the only legal bread after the war); the population however dubbed it “Hitler’s Secret Weapon” because they disliked it so much. However, it was a success: the government was able to keep the supply plentiful enough that bread was never rationed during the entire war.

Fresh, fluid milk was limited, so the Ministry of Food created two different types of powdered milk. One was “Household Milk“, dried skim milk for general consumption. The second was National Dried Milk, a dried “full cream” milk powder aimed at feeding infants.

A National (aka Government) Cheddar was made. All cheese-making resources and capacity were diverted to cheddar, with only effectively trace amounts of a few other cheeses still being made. [4]For instance, a very small amount of farmhouse Wensleydale was still made on a few isolated farms producing small amounts of milk, making it impractical to try to get the milk to a dairy — and transportation resource controls restricted sale of the cheese to the very local area only. It would take the British cheese industry decades to recover.

From July 1942 onwards, there was National Dried Egg, courtesy of the U.S. One packet of the powdered, dried egg was the equivalent of one dozen eggs.

There was also a National Butter and two types of National Margarine (more on those further below.)

Meat in Britain during World War Two

A Sainsbury’s grocery store worker clips ration coupons for customer purchasing bacon. March 1943. United States Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division.

Meat, of course, did not escape rationing, and in fact, was the last thing to come off the ration list, in 1954.

First of all, some “meats” were not rationed. For those who wanted it, horse meat was not rationed (housewives resisted buying beef on the black market, as you couldn’t be sure you weren’t ending up with horse after all.) Offal and sausages were only rationed from 1942 to 1944. But offal was still scarce (for the few that wanted it at any price), and the sausages had little meat in them, and much filler. The Ministry of Food passed a regulation that sausages had to contain at least 10% meat.

Meat pies were not rationed, though the meat in them was likely to be Spam. Spam from America was plentiful, and came to be seen as a godsend. Spam for meals would be fried in a frying pan, or battered and fried in oil with chips.

Fish was not rationed, partly because the Ministry of Food couldn’t find an effective way to ration it, given the underlying principle they followed that rationed items would only be those of which they could guarantee constant supply, and supply was governed by the natural scarcity of how many fishermen were willing to put out to sea with submarines lurking under them at any given time. Consequently, there were always very long queues outside fishmongers.

Tinned Snoek, a type of fish from South Africa [Ed: Thyrsites atun], became widely and easily available off-ration from January 1945 onwards, but was not popular owing to it being very oily, extremely bony, and having a taste that people just couldn’t place.

At the same time, the Ministry of Food made whale meat available off-ration as well, and encouraged people to eat it, releasing recipes, etc. But housewives complained that they just couldn’t get the taste out of it, even after soaking it overnight in vinegar, and boiling it all day.

A large tin of sausage meat from America [Ed: we’re uncertain at this point which. Perhaps Wilson’s Mor.) proved to be popular. It required a lot of points to be allowed to buy it, 16, but the tin was large enough for several meals, and had on top of the sausage meat nearly ½ pound of fat, which was really useful as a cooking fat.

Rabbit keeping became popular. They provided a ready source of meat, as they breed year round, and you could even sell the rabbit skin to be used for boots, coats, etc.

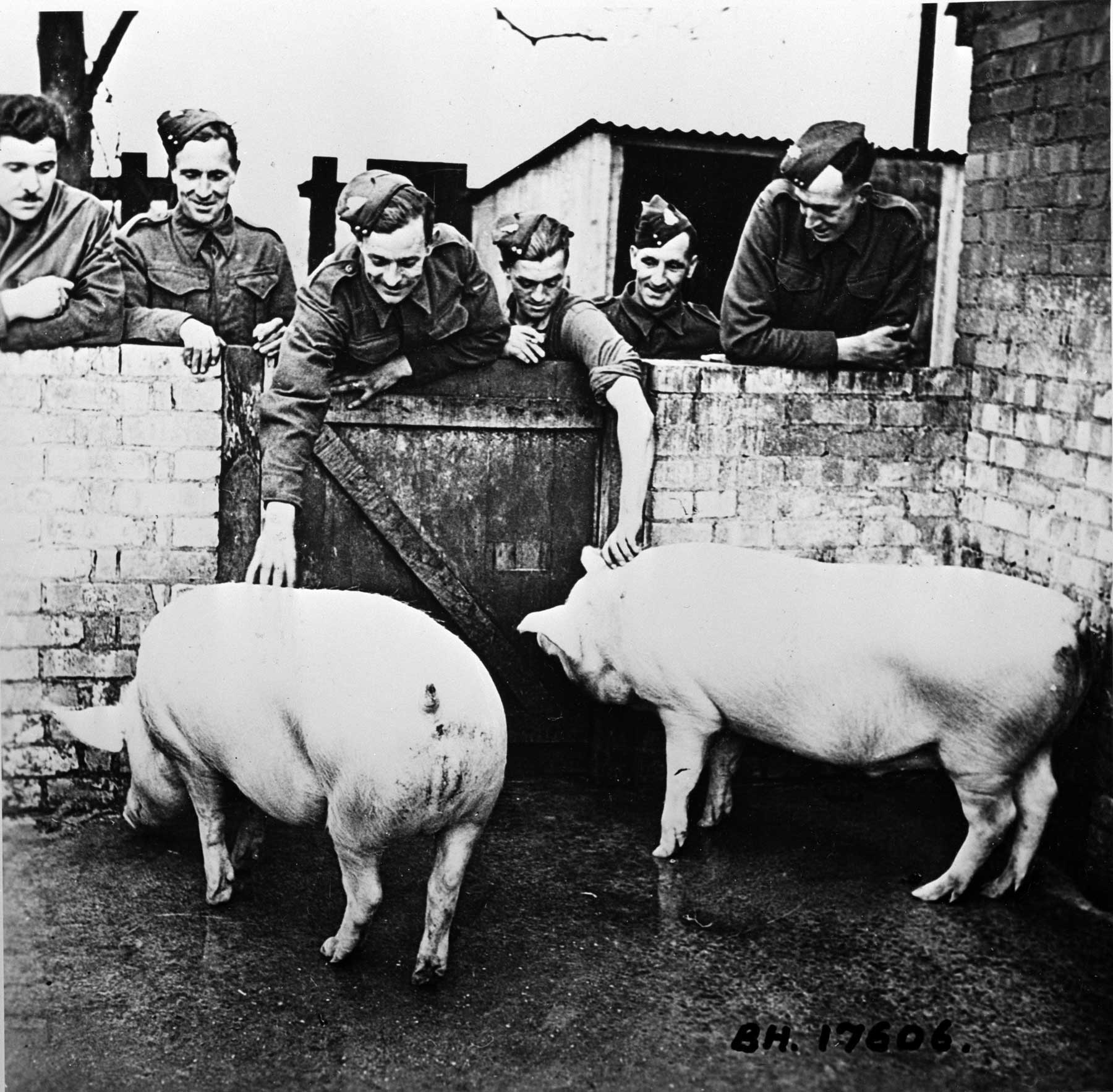

Pig and chicken clubs

In 1940, millions of commercially-farmed hens had to be killed and sold off as food, as there was a shortage of stuff to feed them. This led to an egg shortage, and egg rationing of 1 egg per person a week. Expectant mothers and vegetarians were allowed two eggs a week.

Consequently, people who hadn’t kept chickens, and could, starting keeping them in their back gardens, because that meant you had unrationed eggs. The catch was, you had to give up your egg ration, but you got entitlement for grain rations instead for your chickens. The Savoy Hotel in London had its own chicken farm, set up by Hugh Wontner, managing director of the Savoy hotel from 1941 to 1979. This supplied the Savoy with its own unrationed source of chicken and eggs. (They were still required to ration them on their restaurant menus to customers, however.)

March 1943. Poultry club in Eaton Square, London, run by air raid wardens. They were allowed rationed feed for the hens, and shared the eggs. United States. Office of War Information.

Communities set up neighbourhood pig clubs. Together, the club would buy a pig, then feed it scraps from the households involved. If you belonged to a pig club, the fact that you did was registered, and you had to give up your meat coupons. If you kept a private pig, you had to register the pig, because half was supposed to go to the government, but not everyone registered their pigs.

In many towns, the councils put food waste bins in the streets: if you weren’t part of a pig club, in there went peelings and scraps to be sent to farms to feed pigs.

Pig clubs added thousands of pounds of pork to tables. Even soldiers at permanent stations had pig clubs. United States US Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division. April 1943.

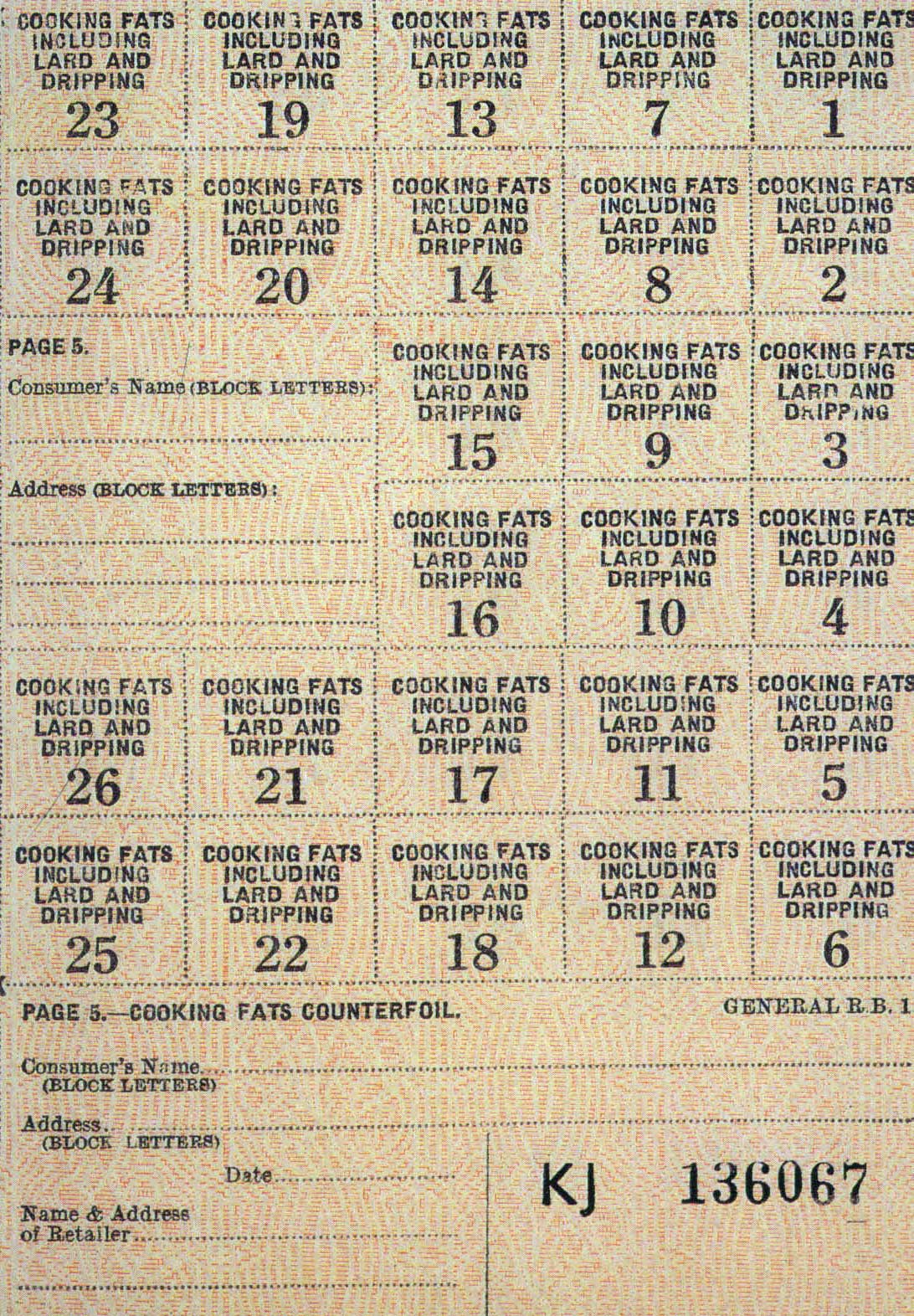

Fats

Fats page in a ration coupons booklet

Fats were on ration as they were also used for military items such as explosives and lubricants.

There was a National Butter made, to help replace the reduced butter supplies from New Zealand. People were inventive in how they boosted the supply of butter at home. Some people recalled that you’d do things like sweet talk the women at work canteens to put lots of butter on a scone, and then not eat it, but bring it home and scrape off the butter for use at home.

As well, there was a National Margarine: in fact two types, a standard and a special which was, in theory, of slightly better quality than the standard, though some people said even it tasted like melted candles.

Before the war, a middle-class British household tended to put butter on the table, and reserve margarine for cooking purposes. But because the rations for the margarines were more generous than for the butter, margarine worked its way out of the kitchen and into the dining room. Some people would mix the margarine with their butter ration for better taste at the table.

Many would use beef dripping as a spread on their bread in place of butter or margarine.

Glycerine and paraffin wax were so popular as substitutes for cooking fat that the Ministry of Food finally restricted sales of them for ‘medicinal purposes only.”

Canadian Red Cross parcels for Canadian, British and Allied prisoners of war were preferred over British or American parcels because the Canadian parcels always included tins of proper butter; [5]Note that it wasn’t that the Canadians were being more generous, though: it’s simply because margarine in Canada was illegal at the time, so they literally didn’t have any to send. See: Margarine in Canada. the British or American parcels had margarine instead 70% of the time.

Restaurants

A page from Winston Churchill’s ration book, 1941. United States Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division.

In July 1940, restaurant restrictions started coming into effect. The first regulation was that in one meal you could not have both a meat and fish dish. So a fish starter, and meat main course, was out.

In June 1942, two additional restaurant restrictions came into effect. The first was that no restaurant meal could have more than three courses. The second was that no restaurant could charge more than 5 shillings for a meal (alcohol and coffee excluded.) This had the desired effect, of course, of causing restaurants to be more frugal in what they chose to offer, or serve smaller portions of it, so that they could still make a profit on the meal. To ensure that restaurants didn’t just try to get around this through “cover charges”, the restriction also stipulated that the highest cover charge that would be allowed was 7s. 6d.

“You need no ration card for restaurants, although a waiter will serve only one meal to a person at a sitting, and that limited to three courses or five shillings expenditure. Swanky places get around the quality barrier by adding a stiff cover charge, but the three courses are never exceeded. A soup or hors d’oeuvres, an entrée and a dessert are regulation. Coffee and drinks are extra. The maitre d’hotel or waiter may “save” a portion of joint for old customers, but a late diner will inevitably find the menu exhausted and only sausage or mushrooms available.” — Albin E. Johnson. Europe: Where the Cupboard is Almost Bare. Rotary International: The Rotarian. September 1943. Vol. 63, No. 3. Page 18.

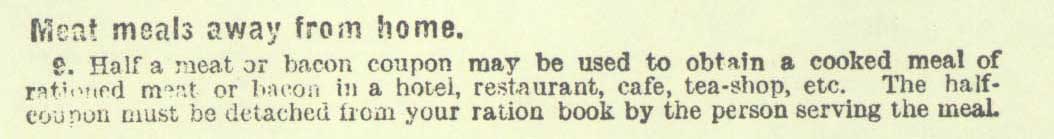

Ed note: There was mention in at least one edition of the ration booklets that meat coupons were required to be used at restaurants. It may be that that regulation was printed, but never brought into force:

Mention of ration coupons required at restaurants

Fish and chips were not rationed. Consequently, fish and chips, which before the war had been seen as just a working-class food, made its way upward to become a food that all Britons ate. Your local chippie could also sell you meat pies, as they were not rationed, either — though the meat in them was more likely to be Spam than anything else.

Canteens

One thing that is often not understood about food rationing at home is that in its calculations, the Ministry of Food expected that rationed home food would be supplemented by meals at work and at school.

Before the war, only about 250,000 school meals a day were served; by the end of the war, school meals happened just about everywhere, feeding about 1,850,000 children a day.

The Ministry made it compulsory for any factory over a certain size to open a canteen to feed its workers. The number of factory canteens consequently went from 1,500 in 1939 to 18,500 in 1945.

Factory canteen, 1943. United States Office of War Information, Overseas Picture Division.

A convoy of mobile canteens would move into bombed areas to feed residents and rescue workers for free, coordinated by the Ministry of Food. These mobile canteens were largely funded by donations from the U.S.

British Restaurants

Public eating centres called “British Restaurants” were set up across the country. The driving force behind their creation was a Mrs Flora Solomon, who was in charge of Marks & Spencer’s staff canteens at the beginning of the war. She was inspired by seeing the Londoners’ Meals Service, which London County Council started in September 1940 to feed those who had been bombed out of their homes. She gave the idea to Lord Woolton, whom she knew socially. He backed the idea, and asked her to get it started. She got permission from Simon Marks, one of the owners of Marks & Spencer, to use some of her work hours towards the setup.

She set up the first “Communal Feeding Centre”, as she called it, in the Kensington area of London, using Marks & Spencer’s store personnel as staff, then set up one in Coventry after the blitz bombing it suffered on 14 November 1940. The Marks & Spencers store in Coventry had been bombed out; since the staff had nowhere to work, she pressed them into service for her Feed Centre there, as well. Her plan was that once the Communal Centres were up and running, they would be turned over to locals in the area to run.

One opened in Newcastle on 6 October 1941, with the Duchess of Northumberland and the Lord Mayor of Newcastle having lunch on the first day to help promote it. The menu there in 1941 was Soup 2d (1p); Meat with 2 Veg 7d (3p); Sweet 2d (1p); Cup of Tea 1d (½p).

Churchill liked the idea very much, but he didn’t approve of the name “Communal Feeding Centres”. He thought it smacked of socialism, and suggested “British Restaurants” instead, and so, as of January 1942, “British Restaurants” they were.

The restaurants were actually more like canteens. They were set up in church halls, town halls, school halls, etc., and run by Local Food Committees on a non-commercial basis. They would usually have restricted hours of opening, operating just at main meal times such as noon to 2:30 pm, etc..

All meals were ration free. The only rule was that you could only have one serving of either meat, game, poultry, fish, eggs, or cheese. You couldn’t have two from that list at the same meal.

They were also relatively inexpensive. The set maximum price allowed was 9d, though even that would likely only have been charged in London where operating costs would be higher.

The British Restaurants served basic foods such as sausage, mashed potato, gravy, or minced beef with parsnips, greens and potatoes. There was also puddings and custard.

Some of the British Restaurants supplied packed meals for working people such as miners. The British restaurant in Chopwell (in what is now Tyne and Wear County; previously Durham) advertised the following food to go: meat pies, sausage rolls or Spam sandwiches at 4d each; ham or bacon sandwich at 5d; teacakes with butter and jam on them, 3d.

By November 1943, there were 2,145 British Restaurants. Less populous areas had Food Distribution Centres, popularly called “Cash and Carry Restaurants”; they were supplied by a British Restaurant in a larger area.

Any food waste from the restaurants went to local pig clubs.

Population Health

The government was not simply concerned that people had basic quantities of basic foods: they also considered the overall population health as understood at the time to be vital to the war effort.

Doctors regularly visited schools to check the nutrition and health status of children. Schools dosed students up weekly with Virol [6]Virol was made by the Bovril company; production stopped sometime during the war as it became too costly to make., a bone-marrow laxative tonic sweetened with malt, to keep them regular. School meals became free for poorer children.

Children under five got cod liver oil; those under three got daily milk (fluid or full-cream reconstituted from National Dried Milk), and orange juice as well. Mothers picked up the bottles of cod liver oil and concentrated orange juice (both provided by the U.S.) at clinics called “Welfare Centres” that were set up. (See also: Mock Orange Juice, Rose Hips)

Though candies were rationed, cough drops were not. Not many children, however, liked cough drops enough that they considered them to be considered an acceptable substitute for candy.

Every national food product that the government created, and every suggested recipe released, was gone over with a fine tooth comb by dieticians, nutritionists and Home Economists.

The one unhealthy thing about the war time food, by today’s standards at least, was the amount of salt prevalent. Salt was unrationed, so it was used freely to try to give some interest to the monotony of the admittedly plain-tasting food.

The result of these efforts was that, despite the deprivation, the British population actually ended the war tremendously fit and healthy: healthier than they had been before, or have been since. Children in general were even taller and heavier than those before the war. Infant mortality rates went down. The average age of death from natural causes increased, meaning civilians just plain lived longer.

Interestingly, the war-time precaution of night-time blackouts caused the number of people killed by night-time road accidents to double over pre-war figures, even though there were fewer journeys by car owing to petrol rationing.

Wartime Kitchens in Britain

Kitchens in wartime Britain were much as they had been in the 1930s before the war. Most kitchens had gas stoves. Coal-burning boilers provided hot water for both kitchen use and heating the home through radiators. Hot water from the tap was used carefully, though, because the coal used to heat it was rationed. Most homes did not have refrigerators yet [Ed: nor were they common yet in North America], so bottling (aka canning) was still a skill practised at home to preserve food, and there was a lot of shopping daily to pick up fresh produce.

A ‘Saucepans for Spitfires’ campaign claimed much of the aluminum cookware in kitchens. It later emerged that the government didn’t actually need this aluminum; it was more of a morale booster to let people feel that they were helping.

Those people with relatives and friends abroad were fortunate, because food packages from them to help bolster or brighten kitchen pantries got through surprisingly often.

It was illegal to feed human food to pets, even bread to birds.

Bread wasted – Miss Mary Bridget O’Sullivan was fined a total of ten pounds, with costs, for permitting bread to be wasted. It was stated that her servant was twice seen throwing bread to birds in the garden, and when Miss O’Sullivan was interviewed she admitted that bread was put out every day. “I cannot see the birds starve”, she said.” — Bristol Evening Post. 20 January 1943.

The Great Onion Scarcity

A persistent shortage of one item particularly exasperated house-wives: onions.

Onions disappeared from the shelves of greengrocers early in the war. Previously, they had been imported so cheaply from Bermuda, Brittany, and the Channel Islands that they weren’t being grown in large quantities in Britain. Onions became so rare that they would be prizes for raffles and contests. In February 1941, the staff at The Times of London newspaper held a raffle for a one-and-a-half pound onion, which raised £4 3s 4d.

In that same month, the Minister of Agriculture, Robert Hudson, no doubt hearing frustration from his own wife, announced the intention to increase domestic onion production by 15 times. By 1942, the Minister announced that the onion shortage was in theory alleviated, though an American rotarian, reporting on a visit to London he had done in the second week of January 1943 puts this claim in doubt:

“Served as a side dish at our luncheon of the regular three-course meal, which Englishmen religiously impose upon themselves in conformity with ration regulations, was a medium-size boiled Spanish onion. “You’ve been robbing a bank or playing with the black market,” exclaimed the astonished husband. “Neither,” explained his proud wife. “Michael (her son and an officer on a destroyer guarding trans-Atlantic convoys) brought these from Bermuda on his last trip and I’ve been saving them for just such an occasion.” — Albin E. Johnson. Europe: Where the Cupboard is Almost Bare. Rotary International: The Rotarian. September 1943. Vol. 63, No. 3. Page 16.

Rationing allowances

Rationing allowances fluctuated during the war (as well as during the post-war period).

Sample 1943 rations of basics for a week for 1 person:

3 pints of milk

3 ¼ Ib – 1 Ib meat

1 egg a week or 1 packet of dried eggs (equal to 12) every 2 months

3 to 4 oz. cheese

4 oz. combined of bacon or ham

2 oz. tea, loose leaf

8 oz. sugar

2 oz. butter

2 oz. cooking fat

Christmas ration bonuses

Here are the Christmas bonuses that were given for the years 1946 through 1949 inclusive:

“Christmas bonuses of the past four years have been:

Sugar: 1949 nil; 1948 8 oz.; 947 24 oz.; 1946 24 oz.

Sweets: 1949 6 oz. for all; 1948 2 oz. for all; 1947 4 oz. for all; 1946 8 oz. for under 18 and over 70 only.

Meat: 1949 nil; 1948 nil; 1947 6d. worth; 1946 8 d. worth;

Fats: 1949 4 oz.; 1948 nil; 1947 nil; 1946 nil.

Tea: 1949 temporary ration increase from two- to two-and-a-half oz.; 1948 4 oz.; 1947 nil; 1946 nil.”

Src: Christmas Food Bonus Prospect. Portsmouth, England: Portsmouth Evening News. 13 November 1950. Page 6, col. 4.

Rationing Timeline

Note that rationing continued in Britain for nine years after the end of the war. The reason given was to help free up food to feed the starving European populations.

- 1940 – January 8: the first foods rationed were butter (4 oz), sugar (12 oz) and ham or bacon (4 oz), per person per week;

- 1940 – March 11: Meat in general was added to the ration list. This wasn’t done by weight, but by price. You could spend per person up to 1 shilling and 10 pence on meat, any meat, any cut, which was about 23 cents American at the time. But obviously, cheaper cuts gave you more meat for that price. The Ministry of Food estimated that it averaged out to be about 1 pound (450 g) of meat a week per person;

- 1940 – July: tea, 2 oz. tea per person, per week;

- 1941 – March: Jam, marmalade, syrup, and treacle added to list (8 oz. per month);

- 1941 – May 5: Cheese added to ration list. 1 oz. per person per week, increased a month later in June to 2 oz. per person per week;

- 1941 – June 1: Clothing added to ration list;

- 1941 – July: sugar ration doubled for summer months to encourage people to make their own fruit preserves;

- 1941 – November: Controls on liquid milk;

- 1942 – January. Rice and dried fruit added to ration list;

- 1942 – February 9: Condensed milk, breakfast cereals, tinned tomatoes, tinned peas, and soap added to ration list;

- 1942 – March: Gas and electricity are rationed;

- 1942 – July 26: Sweets and chocolate added to ration list;

- 1942 – August: Biscuits added to ration list;

- 1942 – December: Oats (flaked and rolled) added to ration list;

- 1943 – June: Your jam (or syrup) ration could be taken in sugar instead;

- 1943 – Sausages added to ration list;

- 1945 – May 27: Bacon ration cut from 4 oz. to 3 oz., cooking fats from 2 oz. to 1 oz., and part of the weekly meat allowance (reduced to 1 shilling and 6 pence by this point) had to be taken in corned beef;

- 1946 – Bread rationing introduced on 21st July [7]Bread rationing from July 21st. Manchester, England: The Guardian. 28 June 1946;

- 1947 – Potato rationing introduced;

- 1948 – July 25: Flour & bread rationing ends;

- 1949 – March 15: Clothing rationing ends;

- 1950 – May 19: Rationing ends for fruit (tinned and dried), jellies, mincemeat, syrup, treacle and chocolate biscuits;

- 1950 – September: Soap rationing ends;

- 1950 – Sliced, wrapped bread allowed again at stores;

Shoppers queue in Bristol, England in the 1950s to get a rationed food item. Paul Townsend / flickr.com / 2013 / CC BY-ND 2.0

- 1951 – Churchill campaigned on finally abolishing government wartime controls such as rationing, and ID cards, with his “Set the people free” campaign. In doing so, he was able to channel the frustration of women in particular into an election victory for him over the previous Labour government. Women were angry that rationing had been kept up by Labour after the war. It was women, not men, who had to wait in lines to get into food stores, and then try to produce meals with what little they were able to get, while the men were getting extra off-ration meals at canteens at their workplaces (from which women had been expelled, of course, after the war);

- 1952 – October 3. Tea rationing ends;

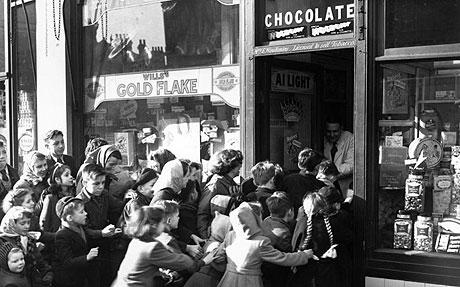

- 1953 – February 5: Sweet (candy) rationing ends;

- 1953 – September. Sugar rationing ends;

- 1954 – July 4: All remaining rationing is abolished.

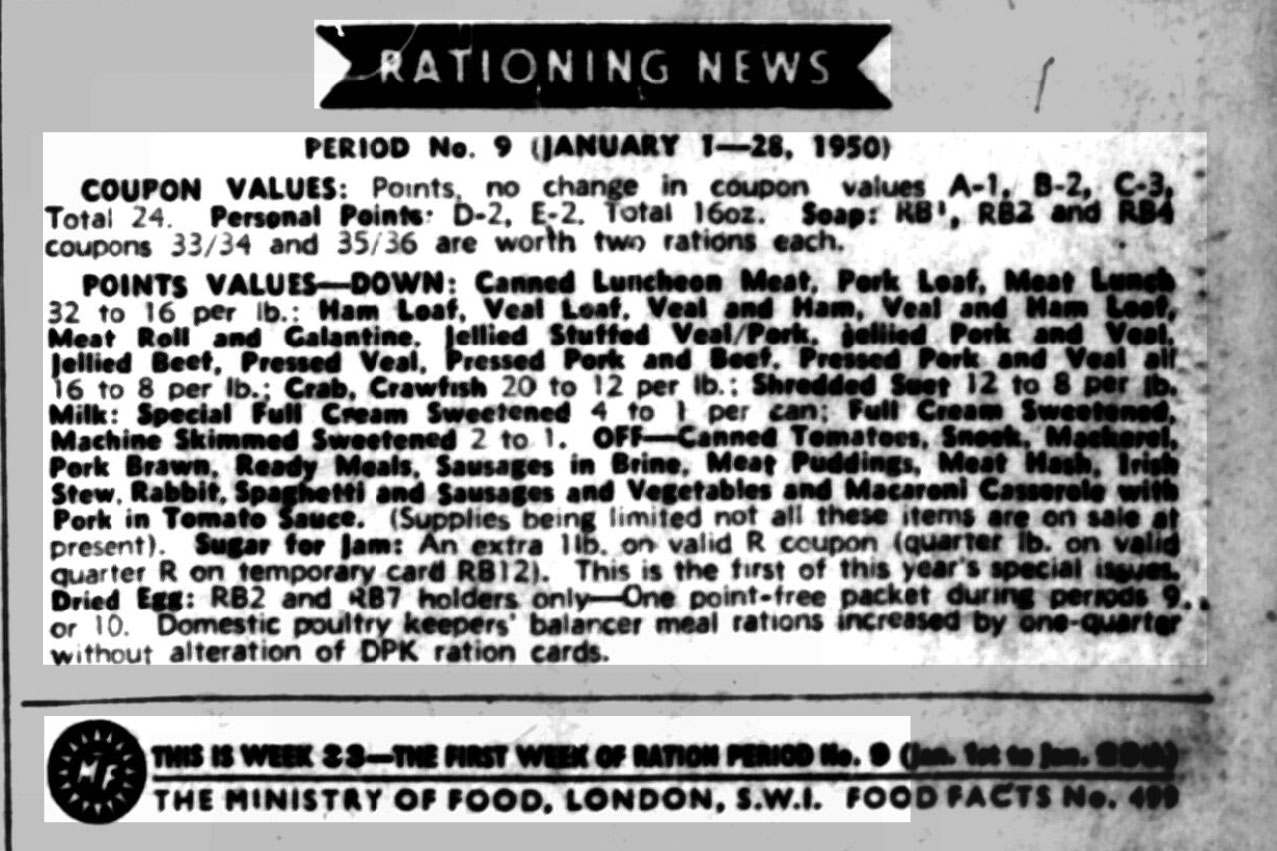

UK rationing changes January 1950. Rationing News. Birmingham, England: Birmingham Gazette. Monday, 2 January 1950. Page 3, col. 6.

Children running into a candy store 5 February 1953 as sweets (candy) rationing ends

Meat rationing ends, 1954.

Literature & Lore

“Lord Woolton Pie: The Official Recipe. In hotels and restaurants, no less than in communal canteens, many people have tasted Lord Woolton pie and pronounced it good. Like many another economical dish, it can be described as wholesome fare. It also meets the dietician’s requirements in certain vitamins. The ingredients can be varied according to the vegetables in season. Here is the official recipe: — Take 1 lb. each diced of potatoes, cauliflower, swedes, and carrots, three or four spring onions – if possible, one teaspoonful of vegetable extract, and one tablespoonful of oatmeal. Cook all together for 10 minutes with just enough water to cover. Stir occasionally to prevent the mixture from sticking. Allow to cool; put into a pie dish, sprinkle with chopped parsley, and cover with a crust of potato or wheatmeal pastry. Bake in a moderate oven until the pastry is nicely browned and serve hot with a brown gravy.” — London: The Times. 26 April 1941.

“Carrot Sandwich Fillings: Add two parts of grated raw carrot to one part of finely shredded white heart cabbage and bind with chutney or sweet pickle. Pepper and salt to taste. OR Bind some grated raw carrot with mustard sauce flavoured with a dash of vinegar.” — Ministry of Food, War Cookery Leaflet 4.

“The number of rabbits we ate shot up, as did pigeons, and like a lot of well-connected people, the family I worked for fiddled the system shamelessly. You see they thought they had been born with an entitlement to a certain standard of living and they really thought that poorer people were better equipped to live on less — even during the war. I don’t think there was any nastiness in it. They just assumed we had always lived on a few scraps of bacon and lots of spuds and that therefore war shortages weren’t so hard for us to bear, whereas for them no butter was a matter of life and death… But about halfway through, in 1943 I think, the house changed. We’d had pretty poor rations like everyone else and then her Ladyship told me one morning that she had organized food deliveries from a relative. This sounded very odd to me. Apart from anything else it was extraordinary for an upper-class woman to admit that she had relatives in trade. I didn’t believe a word of it, especially as it was always the duty of the cook to order all the food. And there was something about her face that wasn’t quite right when she told me….. Then the penny dropped. It was all black market stuff. The meat and eggs and butter were all delivered by a man I’d never seen before and there were never any bills — or at least none that came to me. He would just drop everything on the big kitchen table and leave without saying a word. The amounts were pre-war quantities — huge joints, and butter by the pound….. I was told by her Ladyship by a note rather than in person that the servants’ meals should continue to reflect the ‘current rationing situation.’ In other words the mean old devil wanted me to continue to cook spuds and cabbage for the other servants while the family enjoyed all the black-market stuff. Well, I’m afraid I took very little notice of that I can tell you.” — Jackman, Nancy. With Tom Quinn. The Cook’s Tale. London: Hodder & Stoughton. 2012. Page 191 – 194.

Sources

BBC. On this day. 1952: Tea rationing to end. Retrieved April 2011 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/october/3/newsid_3122000/3122485.stm

BBC. On this day. 1953: Sweet rationing ends in Britain. Retrieved April 2011 from http://news.bbc.co.uk/onthisday/hi/dates/stories/february/5/newsid_2737000/2737731.stm]

BBC. Wartime Garden and Kitchen. With Harry Dodson, Ruth Mott, et al. Episode 6. 1993. Start time: 16:20.

Coren, Giles. Dinner? It was historic. London: The Times. 15 May 2008.

Cryer, Pat. Coping with food rationing in 1940s wartime Britain and the aftermath. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.1900s.org.uk/1940s50s-rationing-food.htm

Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Women’s Land Army Badge. 28 January 2008. Retrieved May 2009 from http://archive.defra.gov.uk/foodfarm/farmmanage/working/wla/

Gilbert, Gerard. A taste of austerity: Can chef Valentine Warner conjure a feast from wartime food rations? London: The Independent. 14 January 2010.

Heick, W.H. A propensity to protect: butter, margarine and the rise of urban culture in Canada. Waterloo, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. 1991. Page 60.

Johnson, Albin E. Europe: Where the Cupboard is Almost Bare. Rotary International: The Rotarian. September 1943. Vol. 63, No. 3. pp 16 – 19.

Jones, Sir Francis Avery. New Concepts in Human Nutrition in the Twentieth Century: The Special role of micronutrients. The Caroline Walker Lecture 1992. Abbots Langley, Hertfordshire, England: The Caroline Walker Trust. Pages 13 – 14.

Lloyd, E.M.H. Some Notes on Points Rationing. In: The Review of Economic Statistics. May 1942. Volume XXIV, # 2. Page 49 – 52.

Longmate, Norman. The Kitchen. In “How we Lived Then – A history of everyday life during the Second World War. Random House. 1971.

Medical News Today. Wartime Rationing helped the British get healthier than they had ever been. 21 June 2004. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/9728.php

Morley, Diana, IWM Marketing Team. “Rationing Begins.” London: Imperial War Museum. 8 January 2010. Retrieved March 2011 from http://food.iwm.org.uk/?page_id=64

Morley, Diana, IWM Marketing Team. “Rationing during the Second World War: London: Imperial War Museum. 8 January 2010. Retrieved March 2011 from http://food.iwm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Rationing-Info-Sheet3.pdf

Pears, Brian. Rowlands Gill and the North-East 1939 to 1945. Chapter 3. Food and Rationing. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.bpears.org.uk/Misc/War_NE/w_section_03.html

The 1940s House: The Kitchen. Discovery Channel. Retrieved March 2011 from http://www.yourdiscovery.com/reality/1940s_house/kitchen/index.shtml

Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina. Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls, and Consumption 1939-1955. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

BBC WW2 People’s War Memories Archives

Bourhill, Pearl. Land Army girl at Horton Farm, Epsom. Article ID A7981563. 22 December 2005. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/63/a7981563.shtml

Collis, Dorothy. Dorothy Collis’s Story. Article ID A4201408. 16 June 2005. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/08/a4201408.shtml

Cowell, Brenda. Rationing. Article ID A2066546. 21 November 2003. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/46/a2066546.shtml

E., Mark. Collaborative Article: Rationing. Article ID A1112680. 21 17 July 2003. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/80/a1112680.shtml

Jones, Stanley H. Its Rationed – Just how did we manage in Trowbridge? Article ID A2294462. 13 February 2004. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/62/a2294462.shtml

Styan, Joan. Wartime Hardships: Rationing in London. Article ID A2756298. 17 June 2004. Retrieved April 2011 from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/98/a2756298.shtml

Wadsworth, Christine. Ackworth People’s War. Article ID A6956724. 14 November 2005. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/24/a6956724.shtml

References

| ↑1 | Frederick Marquis, Lord Woolton, speaking in the House of Lords. FOODSTUFFS: COST OF DISTRIBUTION. HL Deb 03 June 1942 vol 123 page 103 – 105. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The Ministry of Food Exhibition photos: “Ration Book Inside.” Posted by Imperial War Museum 17 December 2009 at http://www.flickr.com/photos/imperial-war-museum/4193034670/in/set-72157622856066225 |

| ↑3 | Bread was never rationed in Britain during the war, though ironically it was for a short period after the war, from 21 July 1946 to July 1948. Some feel that the reason Prime Minister Attlee’s government introduced bread rationing was more political than out of actual necessity. Britain wanted two things from America: (a) That America should take over feeding refugees in the British occupied zone of Germany; (b) reconstruction loans and Marshall Plan aid. To this end, Britain needed, frankly, to look needy, even though it had a guaranteed wheat supply from Canada. Bread rationing ended in 1948 shortly after a signed and sealed agreement on Marshall Plan aid was safely in British hands. The complete story is covered by Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska in her “Bread Rationing in Britain, July 1946 – July 1948” in the journal “Twentieth Century British History” (Vol 4, No 1 1993. pp. 57 – 85). |

| ↑4 | For instance, a very small amount of farmhouse Wensleydale was still made on a few isolated farms producing small amounts of milk, making it impractical to try to get the milk to a dairy — and transportation resource controls restricted sale of the cheese to the very local area only. |

| ↑5 | Note that it wasn’t that the Canadians were being more generous, though: it’s simply because margarine in Canada was illegal at the time, so they literally didn’t have any to send. See: Margarine in Canada. |

| ↑6 | Virol was made by the Bovril company; production stopped sometime during the war as it became too costly to make. |

| ↑7 | Bread rationing from July 21st. Manchester, England: The Guardian. 28 June 1946 |