Kansas Skyline. Lane Pearman / flickr / 2012 / CC BY 2.0

Clementine Haskin Paddleford (27 September 1898 – 13 November 1967) was an American food writer and editor. She pioneered writing about food as an interesting, fun topic in itself. She also pioneered linking food [1]In English-language food-writing, at any rate. to where it was grown, or to whom it was made by. She wrote for Gourmet Magazine in its very first issue, and would continue writing for it for nearly 15 years.

- 1 Paddleford’s approach to food writing

- 2 A fervent worker

- 3 Paddleford’s writing style

- 4 Early years

- 5 Education

- 6 Writing for a living

- 7 Overcoming disability

- 8 Paddleford arrives at the top of the food-writing world

- 9 Gourmet magazine

- 10 Legacy

- 11 Other Life Events of Clementine Paddleford

- 12 Books by Clementine Paddleford

- 13 Literature & Lore

- 14 Associated recipes

- 15 Videos

- 16 Podcast

- 17 Further reading

- 18 Sources

Paddleford’s approach to food writing

Paddleford appeared on the food-writing scene at a time when writing was focussed on a scientific approach to cooking through the discipline of Home Economics, which reigned supreme in the first few decades of the 1900s. There was an emphasis on understanding nutrition, standardizing measures, and on teaching uneducated working-class women. These were women, living away from their mothers owing to industrialization and the move to cities, whom middle-class women felt needed to know how to cook and look after their families properly.

Consequently, newspaper coverage about food was focussed on education. The sense of Home Economics discipline in the writing left no room for the appreciation of food as an art, or something to be enjoyed and thought about. The newspaper food columnists seemed to pride themselves on how dry and scientific they could sound, to give authority to their voice. They saw their mission as teaching through passing on facts. There were recipes, a few rare restaurant reviews, and occasionally a piece on a well-known cook or chef passing along sound, economic kitchen ideas to homemakers. The only note of “fun” about fun in newspapers might come from grocery store ads.

Then along came Clementine Paddleford. Her columns marked a sea change in the approach to food writing, both in subject matter and style. She was neither a restaurant critic nor a Home Economics teacher; she was a journalist, reporting on the food that ordinary people actually ate, particularly home- produced food. She liked to include the locale, the cooks and the food producers in the stories because, to her, people and place were integral to the story about the food.

While many remember her focus on traditional, homey American cooking, Clementine would eat anything: bear, muskrat, Chinese 100-year-old eggs, beaver, snake, horse. But she stopped at bugs. She was a fan of oysters (covered at least 21 times in her Gourmet magazine columns), grapefruit (at least 15 times), chutney (at least 14 times), curry (13 times), and honey (12 times.)

A fervent worker

Clementine worked 12-hour days. She would spend every morning, from 5 to 11 AM, on her column for her Herald-Tribune, and then in the afternoons, go to the office, or do field research. Her secretary was Helen Marshall. Paddleford wrote in her own form of shortened words, which Marshall deciphered as she typed them up.

She drank a lot of strong coffee, either French or Italian style, to keep her going. At home, her dinner was often prepared by a maid, and she would often eat it at her desk while still working. When she did cook, she preferred baking to cooking main dishes, because desserts got more notice. She had a personal library of about 1900 cookbooks.

She learnt how to fly a plane, a Piper Cub, which she would use to fly herself around the country to do her research.

Paddleford’s writing style

Paddleford felt that food writing itself should be fun and interesting.

In some of her pieces, you can see her writing reaching to be an art-form. She drew wildly on literary references, while remaining gutsy and down to earth. The journalist in her wanted to connect with her readers and make them feel as though they had to have that food right now — a fact that wouldn’t be lost on advertisers. In one of her columns for the Herald-Tribune, she wrote:

“A tour of smells, our daily tramp through the markets of the town. Catch that savory boiling fat from a kitchen on the Bowery? Cheese, smoked meats, the fish market; and the coffee on Water Street the best of all, heavy, sultry and slightly charred.”

Some colleagues described her as “fanciful” in the way she described food, but she resisted being edited:

“I challenged Clementine more. She had some really weird sentence structure sometimes and if I made any changes in that sentence structure she would get really angry. She wanted things exactly as she wrote it. Exactly as she wrote it.” [2]Joan Rattner, copy editor at This Week. As quoted in Alexander, Kelly and Cynthia Harris. “Hometown Appetites.” New York: Gotham Books. 2008. page 186.

And indeed Paddleford did. In the late 1940s, she gave a piece of her mind to someone at a newspaper who dared change her references to freshly squeezed tomato as “blood” to the milder word, “juice.”

Nevertheless, to other writers, her style could be fair game for sport:

“It seems that our O-My-Darling neighbor, Clementine Paddleford, is growing lyrical. Her rhapsody on Cheese News began “In a cash and carry dairy in the downtown section of Manhattan” urged us to hiawathan “In a cash and carry dairy on the Island of Manhattan”, and then we tried something to the tune of “In a Cozy Corner.” But J.F.H. can’t get any farther than “In a cash and carry dairy every Tom and Dick and Mary is extremely sanitary in a strictly foodish way: they are buying Holland Cheeses, Stiltons, Goudas, Bel Paeses…” — The Knave Week Day Column. Oakland Herald Tribune, Oakland, California. 24 December 1936.

Early years

Clementine was born at Mill Creek near Stockdale, Riley County, Kansas. (Ed: most of Stockdale was demolished in 1957 in preparation for the Turtle Creek Dam, and then eventually flooded in 1962.) [3]Apple, R.W., Jr. A Life in the Culinary Front Lines. New York Times. 30 November 2005.

Her childhood was spent in a world where if you wanted fried chicken for dinner, you started by going out back and killing the chickens. Her father was a Kansas farmer, Solon Marion Paddleford. Her mother, Jennie Stroup Romick, had studied home economics at Kansas State College. The two met while they were both in Manhattan, Kansas, at Kansas State Agricultural College (renamed in 1959 to Kansas State University), though neither of them completed their studies.

The couple first lived on a farm at Mill Creek near Solon’s parents. Her older brother, Glenn Decatur Paddleford, had been born on 29 September 1890. A child born in 1895 died while still an infant, then Clementine came along in 1898.

In February 1906, when Clementine was 8, her father purchased a 260 acre farm south of Stockdale. He paid for it with some money he made off land dealings in the Cherokee Strip in Oklahoma. Her family was well-off enough to have a piano. She got up to practise piano at 4 a.m., then had to help with farm chores at 7 am.

Her parents sold the farm in 1911 and moved in September of that year into Stockdale. Her father there managed the grocery store and the post office. In fall of 1913, they moved to Manhattan, Kansas, where her father purchased a larger grocery store called the “Star Grocery Store.” In Manhattan, the family took in boarders as well.

When she was 15, she wrote small pieces for the Daily Chronicle newspaper in Manhattan, Kansas. For this job, she would drive to the local train station in time to see people getting on the 4 AM train for Kansas City and report on people’s comings and goings as local news.

Education

On 1 June 1917, she graduated from Manhattan High School in Manhattan, Kansas. By the spring of 1918, she had started dating Lloyd David Zimmerman, whom she’d eventually marry. She enrolled at Kansas State Agricultural College which was in Manhattan, Kansas. She was extremely involved at the college, participating in many clubs and sports and becoming the editor of the college’s newspaper, The Collegian. She also joined the Theta Sigma Phi sorority for women in journalism and communications. While doing this, she also wrote a few pieces for the Kansas City Post, and other regional newspapers.

Kansas State Agricultural College, Kansas, USA. Circa 1914. Richard Longstreth. “From Farm to Campus: Planning, Politics, and the Agricultural College Idea in Kansas.” Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 20, No. ⅔ (Summer – Autumn, 1985) / Royal Purple 6 (yearbook). Wikimedia / Public Domain

On 2 June 1921, she graduated with an Industrial Journalism degree from the College. She went on to the New York University School of Journalism and did graduate-level journalism classes 3 nights a week. She shared an apartment near Columbia University with three other girls, including Pauline Richards who was also from Kansas State College.

Lloyd Zimmerman, a graduated engineer now, moved to New York as well, but he ended up having to move to Philadelphia to do sales for Westinghouse a short while later.

Writing for a living

To help pay for her time at school in New York, Clementine did several jobs. She reviewed books for the New York Sun, for The New York Telegram, and for a business magazine called “Administration.” She preferred to review scientific books. The fee for reviewing was 3 to 4 dollars, but you got to keep the book, and scientific books had a good resale value of up to 5 dollars.

She got into writing for the New York Sun with a piece she submitted for their “The Woman Who Sees” column, on the women’s page. The piece earned her a cheque for eight dollars. She did several other submissions for that column (of observations and incidents of city life), some of which she later admitted she made up.

She also worked as a waitress at the Union Theological Seminary, near where she lived, and as a shop clerk at Gimbels, selling umbrellas. She was fired from Gimbels when she objected to a customer banging the counter and calling her “Miss”, in response to which Clementine popped an umbrella open in the customer’s face.

In 1923, Clementine and another friend who also wrote for a living went to Chicago in the spring for the wedding of a friend from Kansas State. Zimmerman was already there: by 1922, his job had transferred him there. While there, Clementine landed two jobs: writing for the Agricultural News Service and editing the Milk Market Reporter. So, she moved from New York to Chicago, moving into a boarding house on East Superior Street where other Theta Sigma Phi sorority women were living, including a woman named Marcelle Laval. Shortly after she moved to Chicago, however, Zimmerman’s job transferred him yet again, this time to Texas.

On 10 July 1923, she and Lloyd got married after he agreed she wouldn’t have to move to Texas right away. They would never actually live together and would eventually amicably divorce in 1932.

Clementine kept working for the Milk Market Reporter, but swapped the Agricultural News Service job for one as a promotional material writer for the Hayes-Loel Company, a PR firm, with clients including Sears.

In 1924, while on a PR assignment for Sears helping with an exhibition of quilts at the Illinois State Fair in Springfield, she borrowed prize quilts from many women for the display. They were stolen, however. and later found in the mud. She only escaped from the angry quilters by fleeing out her office window and over the rooftops.

In September of that year, again while doing PR work for Sear’s radio, she met the associate editor of the Farm & Fireside National Farm Journal. He invited her to be the household editor for the magazine back in New York. She went home for a visit to Kansas, then by November 1924 had moved to New York.

Clementine had been offered, and accepted, complete charge of her department. She emphasized writing stories from direct contact with farm women, as opposed to researching them in libraries. By 1927, she was a power-networker in her field, and a member of the American Home Economics Association. 1927 had started off sadly, though: in January, her mother back in Kansas had died.

Clementine remained with the Farm & Fireside magazine until 1930. The publisher changed its name to Country Home, and there were editorial changes, to get it a larger audience beyond farming families. Paddleford took advantage of the changes to make a change herself. She got a job in June 1930 at the Christian Herald newspaper as housekeeping bureau director. There was a test kitchen there as well. In the same year, her father remarried.

Overcoming disability

In the summer of 1931, she had an operation for cancer which necessitated removing part of her larynx and vocal cords. The doctors had to insert a silver tracheotomy tube permanently in her throat for breathing, with an opening in her throat, which she would conceal with a ribbon around her neck that she arranged to look like a choker. She had to learn to talk all over again, holding a finger over the hole whenever she wanted speak. It gave her a much deeper voice.

While at the Christian Herald, she also wrote for other publications under various pen names such as Clementine Haskin, C. P. Haskin, Mrs. Clement Haskin, and Clemence Haskin. This was to keep her real name associated with her main employers.

In October 1932, American Mercury carried an article by her reporting on how women in church kitchens across the country were feeding the hungry during the depression.

By 1934, she was the editor of Home Echo magazine on the side.

Paddleford arrives at the top of the food-writing world

New York Tribune Building. Built 1875, demolished 1966. Wikimedia / Public Domain

In March 1936, based on the strength of articles such as the depression one, she was offered a job at the New York Herald-Tribune newspaper by Eloise Davison, director of the “Home Institute” at the Herald-Tribune. Paddleford’s title at the Herald-Tribune was to be Food Markets Editor, and it paid 40 dollars a week. The requirement was to produce half-columns on food for 6 days a week. At first, the column appeared with no byline for Paddleford, but within a few months she got her byline. She wasn’t allowed to say where the food she mentioned could be bought. That changed in 1944, though, as the newspaper grew weary of hundreds and hundreds of letters a week from readers asking where they could buy the stuff she mentioned.

Her office at the Herald-Tribune was on the 9th floor. The “Home Institute” at the newspaper had a model kitchen, and by the 1940s their offices were air-conditioned. Her staff in the 40s were Gwen Hall, who arranged the photographs, and Anne Pappas, who did the test cooking for her.

At this time, she was living on the East Side of New York. In 1938, she purchased a summer home on 17 acres in Redding, Fairfield County, Connecticut.

In 1939, King George V and Elizabeth were on their famous North American tour, making sure that when the coming war inevitably came, Canada and America would show up at some point. Eleanor Roosevelt decided to be down to earth and treat them to an authentic American picnic at the Roosevelt’s Hyde Park:

“S.M. Paddleford is the recipient of a highly interesting feature story concerning food served the King and Queen of England during their recent visit at the White House. Written by Clementine Paddleford for the New York Herald, the story describes the four kinds of cookies — lemon, sand tarts, Swedish and fruit cookies — that were baked by a Connecticut woman along with 24 pans of gingerbread, 12 loaves of steamed Boston brown bread and pots of New England baked beans for the picnic that Mrs. Roosevelt had for the King and Queen and 130 guests. A two-crown cake made by a French bakery was also served at the picnic party. It was topped with two small white satin cushions, exact reproductions of the crowns of the King and Queen. The original colors of the precious stones were set in miniature and every detail considered. Two special boxes were made to hold the crowns and after the cake cutting, they were removed and given to the Queen to take home to the little princesses.”

The variety of frankfurters sold at the World’s Fair were also served to the royalty, according to Miss Paddleford, who suggested that Mrs. Roosevelt could have given the vendor spiel that is the popular one at the fair, “Ho-ot dogs a dime! Boneless, skinless, harmless, homeless, who’ll have a dog?” Miss Paddleford frequently sends her column, which appears daily in the New York Herald, to her father S.M. Paddleford, 513 North 16th.” — Social Newsbits. Manhattan, Kansas: The Morning Chronicle. Friday, 30th June 1939. Page 5, col. 1.

In 1940, Paddleford was hired by William Ichabod Nichols, the managing editor of This Week magazine, to write a weekly column in addition to her work at the Herald-Tribune. The magazine was distributed in Sunday newspapers throughout the United States. She wrote for This Week until she died.

In the 1940s, she had a cat named Peter that she was very fond of.

Gourmet magazine

In 1941, she started writing a monthly column, “Food Flashes”, for a new magazine launched in January of that year: Gourmet Magazine. She wrote for Gourmet until 1953. For her column, she covered new food products, their prices, and how to procure them.

In 1943, she had a fourteen-year old girl named Clare Duffé (later Clare Duffé Jorgensen) come to live with her — Clare’s mother, Marcelle Laval Duffé, had been a friend of Clementine’s from Chicago, a member of Paddleford’s Theta Sigma Phi sorority, and a children’s book writer. When Marcelle died in September 1944, she asked Clementine to look after her daughter.

In summer 1944, Clementine’s father died.

In March 1946, she went to Fulton, Missouri, to cover the visit of Winston Churchill there. While everyone else reported on the Iron Curtain speech he gave on the 5th of March, she covered the buffet menu that was served — fried chicken, glazed ham baked with cloves and pineapple, twice-baked potatoes, pickles, canned asparagus, tomato aspic, celery, hot rolls, olives, angel food cake and ice cream. She wrote that a soufflé served to Churchill arrived “with a rapturous, half-hushed sigh as it settled softly to melt and vanish in a moment like smoke or a dream.” [4]Apple, R.W., Jr. A Life in the Culinary Front Lines .

In late June of 1946, she went to France for two weeks, courtesy of Air France, on a trip organized for American journalists. It was the airline’s inaugural flight from New York. While there, she met the Duke and Duchess of Windsor at a reception at Cap D’Antibes. She loved the food in France, and took advantage of every minute there to explore the food. But she said on the way back to New York, “It’ll be good to be home where the ice water flows like champagne.”

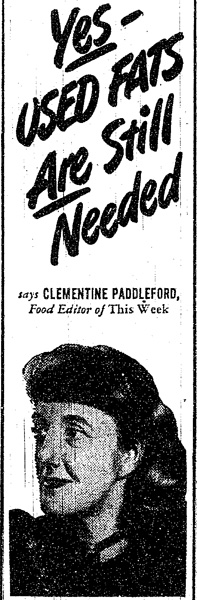

Clementine Paddleford recruited by Agriculture Dept. to encourage people to conserve fats, 1947.

On 12 January 1947, This Week published her article on Duncan Hines, entitled “60,000 Miles of Eating.” It was perhaps in looking at what Hines was doing that she got her idea to start her writing project on “How America Eats.” It was series of articles, each based in a different spot. She’d stay a week in a place, researching thoroughly. Each article would include information about the dish, who cooked it, and why, and a recipe. She rooted the dish in a place. For instance, she covered New England boiled dinners in January 1948, founding the article on a Herman Smith who served it one night to friends in a snow-bound part of Massachusetts.

In 1947, the American Fat Salvage Committee recruited her to be the face of a campaign to encourage women to not give up yet the wartime habit of saving and turning in used fats.

In February 1955, she was included in a group of “celebrities” on a tour of the citrus industry in Florida sponsored by the Florida Citrus Commission. Also in the group was food personality “Ann Adam” (aka Katherine Caldwell Bailey). [5]Editors plan Mt. Dora Stop. Orlando, Florida: The Orlando Sentinel. Sunday, 27 February 1955. Page [unclear in archives], col. 4.

Clementine Paddleford in Florida, 1955. Orlando, Florida: The Orlando Sentinel. Thursday, 3 March 1955. Page 22, col. 2.

In 1960 and 1961, she toured extensively to promote her 1960 book, “How America Eats.”

In the 1960s, her main rival became Craig Claiborne, who dismissed her work:

“The only much-read and much-quoted critic in town was Clementine Paddleford, a well-meaning soul whose prose was so lush it could have been harvested like hay and baled. The truth of the matter was, however, that Clementine Paddleford would not have been able to distinguish skillfully scrambled eggs from a third-rate omelet.” [6]Craig Claiborne. As quoted in Alexander, Kelly and Cynthia Harris. “Hometown Appetites.” New York: Gotham Books. 2008. Page 207.

In 1966, when the New York Herald Tribune finally closed, Paddleford was still writing for it.

Legacy

She died on 13 November 1967, and was buried in Riley, Kansas in the Grandview-Mill Creek-Stockdale Cemetery. After her death, all her papers were shipped to the University Archives of Kansas State University in 1968, as per her will.

In 2001, a woman named Cynthia Harris was hired full-time to process collections in the archives, particularly Paddleford’s. The Clementine Paddleford Papers collection at Kansas State University, covering from 1920 to 1967, was opened to the public on 26 September 2005.

Based on those papers, a book about Paddleford’s life, “Hometown Appetites: The Story of Clementine Paddleford, the Forgotten Food Writer Who Chronicled How America Ate” has been written by the team of Kelly Alexander, and Cynthia Harris.

Other Life Events of Clementine Paddleford

- 1948 — received the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award;

- 5 March 1949 — received the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award;

- 30 April 1949 — The Saturday Evening Post publishes an article about her;

- 1949 — by this point, Paddleford is making approximately $25,000 a year;

- 17 Feb 1951 — received the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award;

- 30 September 1951 — received her Solo Flight Certificate;

- 1951 — went to Copenhagen by invitation of the Danish government;

- 1951 — returned to Paris for another short visit, and also to Rome and Florence, to investigate how Americans ate abroad. By this time, she had travelled so much that she became a member of the United Air Lines 100,000 miles club and by June of that year, there were 21 pieces towards her “How America Eats” collection;

- 1952 — added to her real estate holdings by purchasing a 150 acre farm on the Kennebec River in Maine, near Bath, Maine. She largely purchased it for Claire Duval, who was married in June of that year to a John Jorgensen. The couple would have three children;

- 1953 — went to London for the coronation of Elizabeth II. Paddleford focussed on the food served, as well as Harrod’s Food Hall (she was not actually invited to the luncheon; she spent all her time interviewing everyone involved in preparing it);

- 10 December 1953 — received the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award;

- 28 December 1953 — Time Magazine calls her the “best-known food editor in the United States”;

- 3 March 1954 — received the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award;

- August 1955 — rather than move from the building in which she was renting an apartment in New York, which was being sold, she bought it — for $15,250;

- 7 November 1959 — received the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award;

- 11 November 1961 — received the New York Newspaper Women’s Club Award;

- 15 March 1964 — received the Society of Gourmets for the Leisure Arts Award.

Books by Clementine Paddleford

- Patchwork Quilts (c. 1928, based on her work at the agricultural fair in Chicago).

- A Dickens Christmas Dinner. 1933.

- Twelve favorite dishes. (With Duncan Hines and Gertrude Lynn). 1947.

- Recipes from Antoine’s kitchen : the secret riches of the famous century-old restaurant in the French Quarter of New Orleans. United Newspapers Magazine Corp. 1948. 21 pages. Illustrated.

- How America eats : best recipes of 1949 / selected and tested by Clementine Paddleford. New York : United Newspapers Magazine Corp., 1949. 20 pages.

- A Flower for My Mother. New York : Holt 1958. 64 pages. (First published in the Christian Herald, May 1936. The 1958 version was expanded.)

- Belgium, a land of plenty; a series of articles on the temptations of the Belgian cuisine. (Published first in the New York Herald Tribune.) New York, Belgian Government Information Center, 1955. 31 pages, with illustrations.

- How America Eats. New York: Scribner. 1960. 495 pages, with illustrations.

- Clementine Paddleford’s Cook Young Cookbook. New York: Pocket Books. 1966. 124 pages.

- The Best in American Cooking. New York: Scribner. 1970. 312 pages, with illustrations.

In 1961, she was on a book tour to promote “How America Eats.” One of her stops included an invitation to dinner at the “Bayshore Potluckers Club” in Sarasota, Florida. The reporter noted that Clementine’s notepad and pencil were busy making notes of all the potluck dishes that had been brought. As a sign of her popularity, there was a homemade cake with her name on it, and people sang “Clementine.”

Literature & Lore

In 1949, Paddleford described her food journey to date:

“I’ve just travelled eight thousand miles from the East Coast to the West, into the South, into big cities, little towns, to see how America eats, what’s cooking for dinner….. I have knocked at kitchen doors, spied into pantries, stayed to eat supper… I have interviewed food editors in 24 cities… I have shopped corner groceries, specialty food shops, supermarkets, public markets, push carts.” — Clementine Paddleford, February 1949, This Week Magazine.

A Trip Through the Plant Where Bartletts, on Sale Here Now, Were Picked:

“A wonderful trip through California’s brown hills, tawny hills, made gold and brown by sun-cured grasses, made lavender and gray by sage and green spotted by cactus. A morning last week, under a hot sun and a turquoise sky, we head out of Sacramento and up the river valley straight into the pear country around Placerville.

Past the hop fields, the vineyards, the English walnut orchards, past acres of wasteland where gold had been dredged. It was in this area that gold was discovered in 1849. Larks with little yellow trimmings sang lustily. There were grey doves and brown quail. White-faced cattle drowsed in the browning pastures. Nearing Placerville, once called Hangtown, the pear orchards could be seen, spreading over the rolling foothills. Beyond, the slate-colored mountains cut sharply on the skyline.

These were the Bartlett pears, the pears now pyramiding our huckster barrows, the very pears you can buy this morning at your corner store for five cents apiece. Through Placerville’s narrow streets, past Hangman tree with a dummy figure dangling from a noose, past the El Dorado County courthouse to the largest pearpacking plant in the world, owned by the Placerville Fruit Growers Association and built especially for handling pears for the East, for New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago.” — Clementine Paddleford, in The New York Harold Tribune, 23 August 1950.

“Never grow a wishbone, daughter, where your backbone ought to be.” — Clementine Paddleford, attributed to her mother

Associated recipes

Souffléd Macaroni and Cheese Bake

Videos

Clementine Paddleford: America’s First Food Journalist. Panel Discussion with Kelly Alexander, Betsy Wade, Colman Andrews, and Molly O’Neill. Andrew F. Smith, moderator. 2010. Wollman Hall, Eugene Lang Building, 65 West 11th Street, New York.

Introduction to Clementine Paddleford by Cynthia Harris, co-author of Hometown Appetites (biography of Clementine Paddleford). 2011

Podcast

Further reading

Alexander, Kelly and Cynthia Harris. “Hometown Appetites.” New York: Gotham Books. 2008. (Link valid as of August 2021)

Clementine Paddleford. Food Flashes, November 1944. (Link valid as of August 2021)

McRobbie, Linda Rodriguez. The Badass Lady Pilot Who Revolutionized the Art of Food Writing. Mentalfloss.com. 4 November 2015.

Sources

Alexander, Kelly and Cynthia Harris. “Hometown Appetites.” New York: Gotham Books. 2008.

Apple, R.W., Jr. A Life in the Culinary Front Lines. New York Times. 30 November 2005.

Athon, Bobbie. “She Defined How America Ate: Meet Clementine Paddleford.” Topeka, Kansas: Kansas State Historical Society. November 1998.

Barritt, T.W.. The Woman Who Revived a Forgotten Food Writer. (Interview with Kelly Alexander.) Tuesday, 21 October 2008. Retrieved November 2008 from http://culinarytypes.blogspot.com/2008/10/woman-who-revived-forgotten-food-writer.html.

Elving, Belle. Review of “HOMETOWN APPETITES: The Story of Clementine Paddleford, the Forgotten Food Writer Who Chronicled How America Ate”. Washington, DC : Washington Post. 24 October 2008.

Israels, Josef (II). Her Passion is Food. Saturday Evening Post. 30 April 1949. Pages 43, 56-58.

Kansas State Alumni Association. “Clementine Paddleford” in K-Stater Magazine. March 1961.

Kansas State University. Online Exhibit: Clementine Haskin Paddleford: Follow Your Dreams. Accessed August 2019 at https://www.lib.k-state.edu/depts/sc_rev/exhibits/paddleford/index.php

Weigl, Andrea. Food sleuth revisited. Raleigh, North Carolina: The News & Observer. 1 October 2008.

References

| ↑1 | In English-language food-writing, at any rate. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Joan Rattner, copy editor at This Week. As quoted in Alexander, Kelly and Cynthia Harris. “Hometown Appetites.” New York: Gotham Books. 2008. page 186. |

| ↑3 | Apple, R.W., Jr. A Life in the Culinary Front Lines. New York Times. 30 November 2005. |

| ↑4 | Apple, R.W., Jr. A Life in the Culinary Front Lines . |

| ↑5 | Editors plan Mt. Dora Stop. Orlando, Florida: The Orlando Sentinel. Sunday, 27 February 1955. Page [unclear in archives], col. 4. |

| ↑6 | Craig Claiborne. As quoted in Alexander, Kelly and Cynthia Harris. “Hometown Appetites.” New York: Gotham Books. 2008. Page 207. |