Le cuisinier comptable. Augustin Théodule Ribot / wikimedia / 1862 / CC BY-SA 3.0

François Pierre de la Varenne (c. 1615 / 18 — 1678) was a French chef in the first half of the 1600s.

His name is now revered amongst cooks and chefs, because Varenne established the foundation for what would became one of the basics of French cooking: to complement, and not to hide or imitate flavour.

“In the nineteenth century, when French gastronomes went in search of the ancestors of haute cuisine, they quickly identified La Varenne’s Cuisinier as the seminal work of the canon, a status it retains today.” [1]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2009. Page 61.

See also: French Food

Early years

No one is certain where or when Varenne was born. He is presumed to have been born in Chalon-sur-Saône, Burgundy, France, either in 1615 or 1618. He died in Dijon in 1678.

“François Pierre was probably born around 1615 — an eighteenth-century source says he died in Dijon in 1678 at “aged more than sixty years.” [2]Philipe Papillon, Biblioitheque des auteurs de Borgogne (Dijon: P. Marteret, 1742), tome 2, pp. 342 – 343. “Varenne, (Pierre), vint s’établir a Dijon ou il mourut en 1678 agé de plus de 60 ans.” Cited In: Pinkcard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 73. Other sources plump for 1618, though without citing any backup for that date.

“La Varenne” was not actually his name; he added the aristocratic-sounding suffix onto his name for his writing:

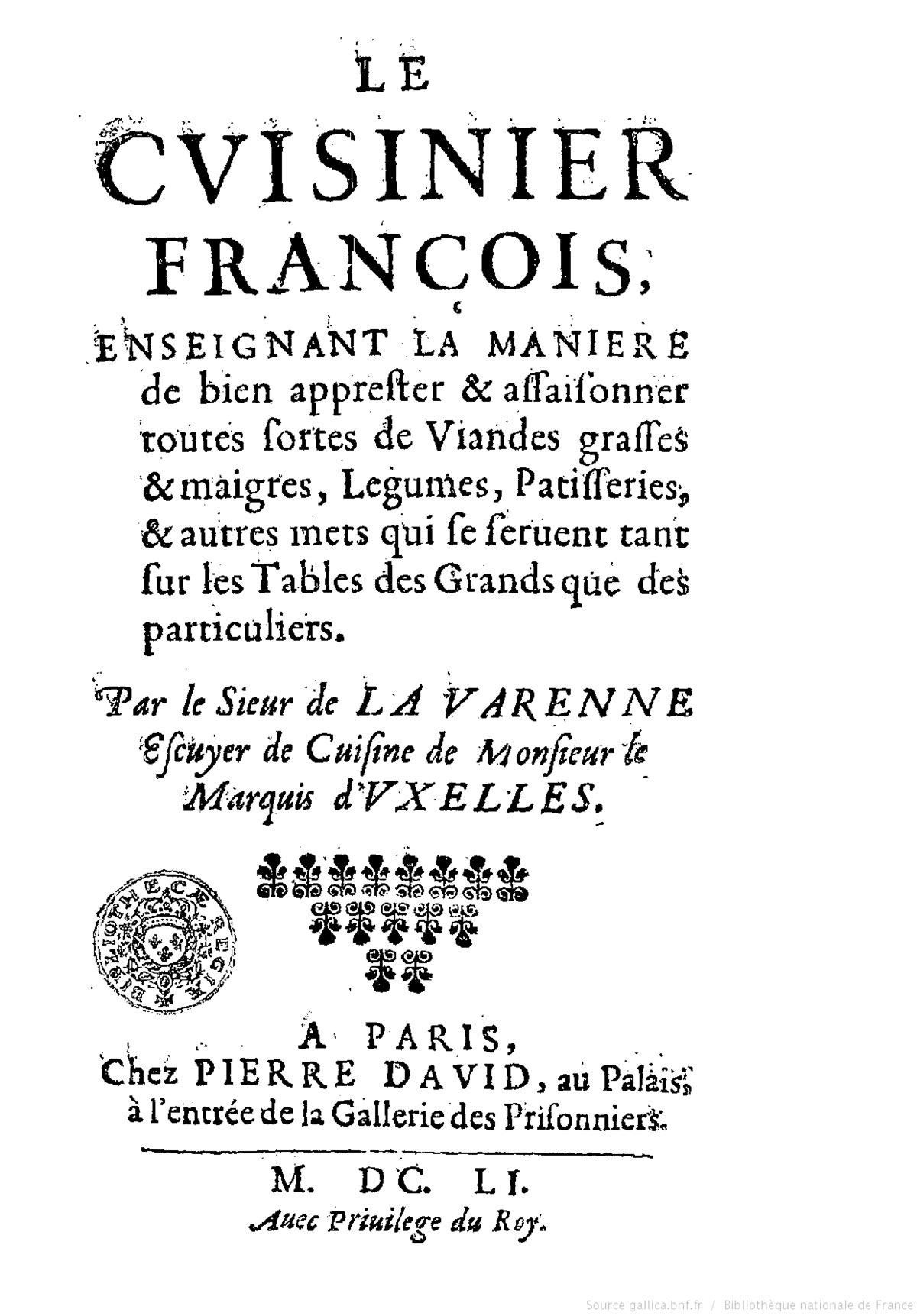

“La Varenne was the nom de plume adopted by a man named François Pierre, who described himself as an écuyer [Ed: roughly, squire] de cuisine in the household of the Marquis d’Uxelles, a Burgundian nobleman of ancient lineage and a lieutenant general in the royal army…. By calling himself an écuyer, La Varenne, servant of a mere marquis, associated himself with an illustrious predecessor [Ed: Taillevent]. Furthermore, by publishing his book under the nom de plume La Varenne he linked himself to another famous example of an ennobled cook [Ed: Guillaume Fouquet, who became the marquis de La Varenne].” [3]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 60.

His career

Varenne possibly got his start at cooking as a young boy in the kitchens of Henri IV (14 December 1553 to 14 May 1610). Henri at the time was married at the time to his second wife, Marie de Médicis (1573 – 1642) [4]Louis XIII became King in 1610. But Marie de Médicis (not to be confused with Catherine de Medici), his mother, served as regent from 1610 to 1614 as he was very young. Even when he became King, she still attempted to run things until he started trying to put her safely out of reach in 1617 in the château de Blois. Louis XIII reigned until his death in 1643; his son, Louis XIV, was king from 1643-1715., later grandmother to Louis XIV (1638-1715.)

By 1644, it’s assumed Varenne was working for the Marquis d’Uxelles. “He seems to have entered the service of the marquis as a young man in the 1630s.” [5]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 60.

In the 1664 edition of his book “Le Cuisinier François”, it says that at the time of its first edition in 1651, Varenne had worked for the Marquis d’Uxelles for 7 years; consequently it’s assumed he worked for the Marquis from 1644 to 1651. Some sources mistakenly name the Marquis d’Uxelles at that time as Nicolas Chalon du Blé (1652 – 1730), made a Marshall of France in 1703. Merriam-Webster, however, has it right: the man Varenne would have worked for was the previous Marquis d’Uxelles, Louis Chalon du Blé (died 1658), who was also Governor of Chalon-sur-Saône.

Le Cuisinier François

In 1651, he wrote his first cookbook, “Le Cuisinier François.”

In 1653, Le Cuisinier François was translated into English and released as “The French Cook”, thus becoming the first French cookbook translated into English.

In Le Cuisinier François, Varenne listed recipes in alphabetical order, as opposed to by meal or course, though he did group together recipes for fish, eggs, meat-free times of the year, etc. He provided no measurements. The book is written in a surprisingly charming, warm fashion, with lots of tips about what to do if a fish is too large, or if you have to delay serving a dish, etc.

He gave several recipes for food wrapped in greased paper and baked in ashes. Wrapping food up in something and baking it in the ashes of a fire or hearth was traditionally a method just used by the poor, who might not have many if any cooking vessels, and some recipes from the time of hearth cooking call for the cook to avoid getting the food smoky. Varenne, however, seems to call for the cooking method both to slowly concentrate the flavours (as opposed, say to boiling, which would leach flavours out), and to impart a smoky flavour that he seemed to want in some dishes.

His legacy

Varenne is said to represent the starting point of French cooking. He codified and defined the point in time where a medieval style of cooking, which had been more or less universal amongst the aristocracy throughout Europe, was replaced in France by a new, uniquely French way of cooking. Varenne rode this trend away from the past and made it a decisive break.

Varenne didn’t do this in isolation. There already was a direction happening around him. Sweet was being separated from savoury. Exotic spices from far-off lands such as cardamon, nutmeg and cinnamon were being taken out of savoury main courses and relegated to sweets. They were replaced with local herbs such as bay, chervil, parsley, sage, tarragon and thyme.

Roux was being used to thicken sauces instead of breadcrumbs. “The first recipe for roux, a combination of fat and flour moistened with wine or stock to produce a single delicious taste, appeared in 1651 by Francois Pierre de la Varenne.” [6]Laudan, Rachel. Birth of the Modern Diet. Scientific American. Vol. 283, No. 2 (AUGUST 2000), page 80.

Varenne did not, however, completely abolish using bread as a thickener, as some sources mistakenly state. Even in the very first recipe of his book, and in many others, he uses bread as a thicker:

“…puis faites seicher vostre pain & le faite mitonner au bouillon de pigeon….” [7] Francois Pierre de la Varenne. Le Cuisinier François. “Recipe #1: Bisque de pigeonneaux”. Page 4. 1651.

Béchamel Sauce is often attributed to him.

He did not claim to have originated the new cooking styles. He wrote that he “found the secret of preparing foods delicately. He did not claim to have invented this style of cooking, although he gained lasting fame by becoming the first to describe it in detail.” [8]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2009. Page 61.

He was part of a generation of cooks making a clean break away from the medieval view that food was medicine, and that ingredients in a dish therefore were to be selected based on their effect on the body (the Greek four humours theory of health that lasted until the end of the Middle Ages):

“…one of the things that distinguished the delicate cooking of La Varenne… from [his] French predecessors and [his] Italian, English, Spanish, and Central European contemporaries is that few of [his] recipes for savory ingredients called for sugar or spices other than black pepper. Fewer than 5 percent of La Varenne’s recipes called for sugar, traditionally regarded as a gentle corrective suitable to all constitutions, and fewer than 1 percent used ginger or cinnamon, which had been ubiquitous as warming agents in the fine cooking of the previous half-millenium. Interestingly, the handful of recipes in the Cuisinier that do use sugar and spice made no reference to these as dietary correctives in the time-honoured Hippocratic manner. La Varenne appears to have included cloves in the stuffing for his entrée of turkey with raspberries because he liked the taste.” [9]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 66.

Varenne raised vegetables in importance, and gave many recipes for vegetables as star ingredients in their own right. “La Varenne gave recipes for some 150 dishes that featured vegetables as principal ingredients, including entrées and entremets that were suitable for every season of the year.” [10]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 77. His recipes also used them in a way that would allow their flavour to come through rather than being disguised with other flavours. His generation of cooks also started to use relatively newly cultivated vegetables such as cauliflower, asparagus, garden peas, cucumber and artichoke.

17th century vegetables. Colleen Galvin / flickr / 2012 / CC BY 2.0

He used New World foods such as Jerusalem Artichokes (which he referred to as “Topinambours”), and gave the first recipes in print for that other New World food, turkey (“dindons”.)

By including salt-water fish and seafood in recipes meant for an inland Parisian aristocracy, his recipes also showed that transportation links (to bring the fish and seafood inland and have it arrive in a fit state to eat) were improving, becoming safer and more reliable.

“La Varenne published recipes for more than forty kinds of fish and seafood, the majority of which were saltwater varieties (older cookbooks had relied heavily on a few freshwater specifies, so the presence of so many ocean fish suggests how much more sophisticated the Paris market had become.)” [11]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 95.

His motto in food was “Santé, modération, raffinement” (health, moderation, refinement.)

The La Varenne Cooking School, named after him, was founded in 1975 by an Anne Willan at the Château du Feÿ in Burgundy, France.

Books

1651. Le Cuisinier François (Bibliothèque nationale de France, link valid as of August 2019)

1653. Le Patissier Français (attributed to but probably not actually by him)

16xx. Le Confiseur François (attributed to but probably not actually by him)

1668. Le parfaict confiturier

Le cuisinier francois. First page.

References

| ↑1 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2009. Page 61. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Philipe Papillon, Biblioitheque des auteurs de Borgogne (Dijon: P. Marteret, 1742), tome 2, pp. 342 – 343. “Varenne, (Pierre), vint s’établir a Dijon ou il mourut en 1678 agé de plus de 60 ans.” Cited In: Pinkcard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 73. |

| ↑3 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 60. |

| ↑4 | Louis XIII became King in 1610. But Marie de Médicis (not to be confused with Catherine de Medici), his mother, served as regent from 1610 to 1614 as he was very young. Even when he became King, she still attempted to run things until he started trying to put her safely out of reach in 1617 in the château de Blois. Louis XIII reigned until his death in 1643; his son, Louis XIV, was king from 1643-1715. |

| ↑5 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 60. |

| ↑6 | Laudan, Rachel. Birth of the Modern Diet. Scientific American. Vol. 283, No. 2 (AUGUST 2000), page 80. |

| ↑7 | Francois Pierre de la Varenne. Le Cuisinier François. “Recipe #1: Bisque de pigeonneaux”. Page 4. 1651. |

| ↑8 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2009. Page 61. |

| ↑9 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 66. |

| ↑10 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 77. |

| ↑11 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 95. |