Making a roux. Daryn Nakhuda / flickr / 2008 / CC BY 2.0

Roux is a sauce thickener made from equal amounts of flour and butter (you can also use meat drippings for some recipes.)

Sauces made with roux should end up with a smooth texture with a rich, velvety mouth feel.

What is a roux

A roux is a thickener made from starch and fat, typically wheat flour and butter. These are combined with a liquid, such as wine or stock, in a way that produces from the union of all three a single new flavour with a slightly nutty edge to it.

It is used to thicken sauces, soups and stews, as well as sauce-based dishes.

A roux requires slow, gentle cooking over low, steady heat to remove the flavour of the raw flour, and to maximize the thickening power of the starch in the flour.

“…the characteristic velvety texture develop[s] after twenty minutes or so. Sautéing flour removes its raw odor… it also improves the suspension of starch and fat in the flour (maximizing its thickening power.) As the sauce simmers, the starch granules dissolve and disperse, resulting in a very smooth texture that becomes even more refined with prolonged cooking.” [1]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2009. Page 111.

Part of the rational for using a roux, as opposed to just whacking in the butter and flour separately, is that as the butter is melted and cooked, it coats the starch molecules in the flour, which will help prevent them clumping together into lumps when added to the sauce.

Roux based sauces can be convenient in that all the work can be done ahead. They reheat well.

“Except for a final correction of the seasoning just before serving, all the care and attention goes into the early stages of preparation. And because sauces thickened with roux may be cooled and reheated without any loss of flavour or texture, they may be prepared in advance, a factor that led one writer to describe roux-based sauces as “convenience foods at the highest level.” [2]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 111.

One of the kitchen advances required to allow the development of roux-based sauces was a raised stove with even heat, which allowed a cook to easily monitor and frequently stir the sauces, as opposed to having to crouch over a pot over hot coals with uneven heat.

Three types of roux

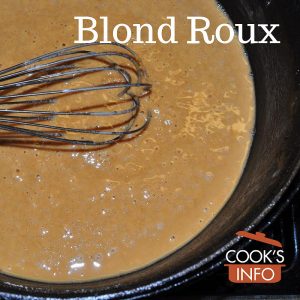

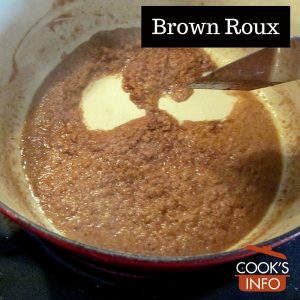

There can be white roux, blond roux, and brown roux.

Brown roux requires a long, slow cooking time in order to acquire its dark brown colour. Brown roux is a base ingredient in Cajun and Creole cooking.

If a recipe does not specific what type of roux it wants, consider a white roux to be the default.

Brown roux. trenttsd / flickr / 2011 / CC BY 2.0

Criticism of roux

At various times in history, roux comes under attack for creating heavy or fattening sauces — or simply, for being old-fashioned.

Carême, in his “The Art of French Cooking in the 19th Century”, writing in the first few decades of the 1800s, was coruscating about some writers who were complaining about the over-use of roux, and said they would be forgottone:

“I do not know why Jourdan Lecointe, who was no doubt as bad a doctor as he was a bad cook, found astonishing, as well as other plagiarists who dragged themselves in his footsteps, that we made roux to bind sauces. All these ignorant men were pleased to denigrate this precious process by treating it as incendiary and corrosive. O pitiful writers, how impertinent and stupid you are! How would fresh butter, and the finest flour, mixed together, and carefully cooked on the ashes of a mild fire, become unhealthy? ….

Now, I ask these ridiculous book-makers, how can this work of butter mixed with flour become corrosive and incendiary? I repeat, if these vain compilers had the slightest sense, they would know that the clarification of large sauces rids them completely of any appearance of roux, but that they are essentially necessary to bind and constitute the sauces; that, without the process of cooking roux, flour mixed with butter would only form an imperfect bond; that, consequently, the sauces, being badly bound, would become essences to the reduction, and would be neither velvety nor succulent. But what does it matter to these ignorant men? Provided that they speak wrongly, provided their written dishes are published, they do not care to degrade the arts and crafts. However, sooner or later comes the enlightened practitioner, who reveals the baseness of charlatanism, and, avenger of science, makes them disappear from the world scene.” [3]Carême, Marie Antonin. L’art de la cuisine française au dix-neuviême siêcle : traité élémentaire et pratique. Paris: Comptoir des Impimeurs-Unis. 1847. Vol 1. Page 56.

The use of roux came under attack again in the 1970s from the supporters of Nouvelle Cuisine:

“In recent times the roux has once again come under heavy criticism and, with the advent of nouvelle cuisine in the early 1970s, many chefs abandoned its use (preferring to thicken their sauces with vegetable purées or using emulsified butter instead.) But, despite its chequered history, the roux remains one of the cornerstones of French cuisine and, when perfectly executed, imparts a slightly nutty flavour as well as an appealing unctuosity to sauces which use it as a base.” [4]Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 907.

Cooking tips

Generally, per 1 cup (8 oz / 250 ml) of liquid such as milk or broth:

-

- Thin sauce: 1 tablespoon of flour / 1 tablespoon of butter

- Medium sauce: 2 tablespoons of flour / 2 tablespoons of butter

- Thick sauce: 3 tablespoons of flour / 3 tablespoons of butter

To make, melt the butter in a saucepan, and slowly whisk in the flour. Cook over low heat for several minutes, stirring constantly.

Cook the roux until white froth begins to appear on the flour, and until it has reached the brownness appropriate for your recipe. If you are making a white sauce, you won’t want any browning happening. If you are making a brown sauce, you want to brown it a bit.

As the roux gets browner, however, it loses some of its thickening ability, because some of the carbohydrates that would be used for thickening have been broken down and used up in the browning reaction process. Consequently, if you are going to brown it, you may want to plan on upping the proportions of flour and butter (equally, of course.)

When the roux is ready, begin whisking in little by little the hot liquid that you are thickening.

Cook the sauce at a very low heat, whisking regularly. You will want to let it cook for at least 10 minutes. When flour cooks even for a few minutes, it develops a starchy taste that will come through in the sauce. By 10 minutes, though, the raw starchy taste will have gone away, and after a few more minutes, any graininess in the sauce from the flour will have smoothed into a velvety texture.

To thin a sauce made with a roux, simply add more liquid and blend in. To thicken sauces at the last minute that are still too thin, consider Beurre Manié. (Do NOT simply add more raw flour.)

A sauce thickened with roux. Oskila / wikimedia / 2008 / CC BY-SA 3.0

History Notes

Before roux was developed as a cooking technique, the standard thickener for sauces, soups and stews was bread.

The first written references to roux being used in a sauce seem to be in the 1651 book, “Le Cuisinier François”, by French chef, La Varenne:

…pour lier la sauce prenez un peu de lard coupé, le faites passer par la poësle, lequel estant fondu vous tirerez, & y mettrez un peu de farine que vous laisserez bien roussir & délayerez avec peu de boullion & du vinaigre; la mettrez en suite dans vostre terrine avec ius de citron, & servez: si c’est au temps des framboises, vous y en mettrez une poignée par dessus. — Francois Pierre de la Varenne. Le Cuisinier François. “Poulet d’Inde a la Framboise”. Page 31. 1651.

We now make roux mostly as a separate item starting from scratch in an empty pot. One early technique though had the flour being added to a pot in which food was already cooking in order to make a sauce right in that pot, and in fact this was more common in the 1650s:

“By the middle of the seventeenth century, a couple of different techniques for making roux had already evolved. The simplest method — and the one La Varenna specified most often — was to sprinkle flour over pieces of meat or vegetables as they sautéed in hot fat (typically lard or bacon fat) until a paste was formed. Moistened with bouillon, wine, and the liquids rendered by the principal ingredient, the lightly browned flour formed a sauce as the food simmered, with the characteristic velvety texture developing after twenty minutes or so.” [5]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 111.

This technique is still used in some recipes.

The first roux in the 1600s were meant to be cooked until a dark, reddish brown colour; thus their name, “roux” (meaning “reddish”). But, “by the mid 1700s, cookbook authors are advising that “roux de farine” (flour-based roux) be cooked until the butter and flour are “a nice yellow.” [6]Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. Page 907.

La Varenne’s Roux

While La Varenne did not invent the concept of roux, he gave the first printed recipes for it.

He used it in many dishes and called in fact for it to be made in bulk and drawn on as needed. “[Roux] was a staple ingredient in the larder of a well-organized kitchen, and La Varenne gave detailed instructions on how to make and store it in a section of his book devoted to kitchen fundamentals.” [7]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 112.

This was his technique for making a dark roux, similar to what is used today in Cajun and Creole cooking:

“His recipe called for flour sautéed in lard (carefully strained of the mammocks or bits of lean pork that floated free as the lard melted) until it was well-browned, an operation that required care, lest it stick to the pan and burn. Chopped onion was added to the browned flour and sautéed until it became soft, a technique that lowered the temperature in the pan, forestalling the scorching that might otherwise occur, while adding sweetness and fragrance as the caramelizing vegetables released their juices into the hot fat and flour paste. At this point, mushrooms, bouillon, and a little vinegar were stirred into the flour-lard-onion mixture and brought to a boil, a step that developed and blended the flavors of the ingredients. Finally, the mixture was strained, removing bits of vegetables, and allowed to cool. The finished roux could then be stored in a covered pot for future use. Because sautéing a truly russet roux — the colour of peanut butter on the way to chocolate — requires about fifteen to thirty minutes or more, depending on the intensity of the heat source and the thickness of the pan, preparing it ahead in large quantities would have made sense. La Varenne recommended warming the portion needed for a particular recipe over hot ashes before adding it to hot cooking liquids. Interesting, the closest descendants of La Varenne’s russet, vegetable-scented roux are found today not in France, but in the Cajun and Creole cooking of southern Louisiana, in which many of the techniques and preferences of the early modern French kitchen are preserved.” [8]Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 112.

Language Notes

Roux is a French word for red; it refers to when the flour in a roux changes colour during cooking. When roux first came on the scene in the early 1600s, it was usually cooked to a deep, reddish brown.

In the 1600s, roux was also referred to as “farine frit” (fried flour). [9]Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. Page 907.

Related Items

Blond Roux

Brown Roux

White Roux

References

| ↑1 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2009. Page 111. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 111. |

| ↑3 | Carême, Marie Antonin. L’art de la cuisine française au dix-neuviême siêcle : traité élémentaire et pratique. Paris: Comptoir des Impimeurs-Unis. 1847. Vol 1. Page 56. |

| ↑4 | Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 907. |

| ↑5 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 111. |

| ↑6 | Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. Page 907. |

| ↑7 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 112. |

| ↑8 | Pinkard, Susan. A Revolution in Taste. Page 112. |

| ↑9 | Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. Page 907. |