Georges Auguste Escoffier in The gourmet’s guide to London (1914) by Nathaniel Newnham-Davis. 1914 / wikimedia / Public Domain

Georges-Auguste Escoffier was a French chef and author who lived from 28 October 1846 to 12 February 1935.

He never worked in private homes; his entire career was spent in commercial, public places. He popularized writing out meal menus in the order in which the items would be served. In the kitchen, he rationalised the division of work between teams, and scrubbed people’s image of a chef into one that was clean, meticulous, and that didn’t drink, smoke or scream.

He created now-classic dishes such as Tournedos Rossini, Melba Toast and Peach Melba. Though most of his cooking would be considered overly elaborate by today’s standards, for his time, he did simplify things by getting rid of the over-the-top food displays, and reducing the number of courses. One person who worked for Escoffier was Ho Chi Minh, who in 1914 was preparing vegetables for him.

Early years

Escoffier was born at Villeneuve-sur-Loup (later renamed to Villeneuve-Loubet), 9 miles (15 km) outside of Nice. His father was a blacksmith and a tobacco grower.

Escoffier was very slight of build, and his father may not have thought him suited for the blacksmith business. Consequently, in 1859 at the age of 13, the young Georges-Auguste started working for his uncle who, three years previously in 1856, had opened the Restaurant Français in Nice (the restaurant stayed in business until 1910.)

“In October 1859, the day after his thirteenth birthday, he took his first communication. It was the end of childhood, and his father told him he was to be a cook. As Auguste recalled in old age, ‘There was nothing I could do buy obey.’ In October 1859, Jean-Baptiste Escoffier took his son Auguste to his first job, as a cook apprentice to his Uncle Francois… Francois Escoffier, already well known in Nice as a restaurant proprietor, had opened his Restaurant Francais in 1856. [1]James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. London: Hambledon and London. 2002. p. 4.

In 1865, Escoffier met a Monsieur Bardoux who was visiting Nice. Bardoux invited him to come to work for him in Paris on Antin Avenue at his “Reine Blanche” restaurant (later to gain fame as the most popular summertime restaurant in France under the name “Petit Moulin Rouge”.) Escoffier accepted; by 1867, he had become “Chef Garde-Manger” and by 1870, he had become Chief Sauce Person of the restaurant.

Franco-Prussian War

In July 1870, Escoffier mobilised as a cook in the French army for the Franco-Prussian War. Not the regular soldiers, though: he was recruited to cook for Marshal Achille Bazaine and other higher-ups stationed on the Rhine. There were two main armies there. One was headed by a Marshal Mac-Mahon, who surrendered his 83,000 soldiers to the Germans on 31 August 1870. This increased the pressure on the remaining army, commanded by Bazaine, forcing it to take refuge inside Metz. Escoffier became part of the besieged French along with 140,000 other French soldiers.

Bazaine surrendered Metz to the Germans on 27 October 1870 (Paris surrendered on 28 January 1871.) Escoffier spent six months at Wiesbaden as a prisoner of war. After the first two months, though, he began working as “chef de cuisine” for Marshal Mac-Mahon and his staff, who were also imprisoned at Wiesbaden (and perhaps overjoyed that Bazaine had finally surrendered so that Escoffier could be sent their way.)

Escoffier was freed in April 1871, and returned to Paris. Sadly, Paris was in the middle of the Paris Commune turmoil, and this time, it was a French army that was about to besiege the city he was in. Escoffier left Paris immediately for Versailles, where the French army was organized from, and went back to work for Marshal Mac-Mahon.

Return to civilian work

In 1872, all was settled and he was able to return to civilian life. From 1872 to 1878, he worked each winter in the south of France, and each summer as chef de cuisine at the Le Petit Moulin Rouge (formerly the “Reine Blanche.”)

In 1874, he started a friendship with the great actress Sarah Bernhardt and remained a lifelong admirer of her. In 1902, he created “Pêches L’Aiglon” in her honour.

Original photograph by Gaspard-Félix Tournachon. seriykotik1970 / flickr / 2010 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Auguste named a peach dessert for Sarah Bernhardt. He first served it at a dinner in 1901 given in her honour at the Carlton by the actor Benoit-Constant Coquelin. The dinner was to celebrate her triumph in Rostand’s L’Aiglon, and the dish was named accordingly. (Filet de Sole Coquelin made its debut at the same table.) The dish did not make much of a stir. For one thing, the idea was noticeably second-hand: Peches Aiglon. Peaches poached in vanilla-flavoured syrup are laid on a bed of vanilla ice cream in a silver timbale and set in an ice sculpture of an eagle. The peaches are sprinkled with crystallised violets and veiled with spun sugar.” [2]James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. p. 205.</span>

He would also record a recipe he called “Sarah Bernhardt’s Favourite Consommé.”

In 1878, he tried his hand at owing his own restaurant in Cannes, buying a restaurant called “Le Faisan d’Or” (The Golden Pheasant) which he ran for two years.

In 1880 (some sources say 1878), he married Delphine Daffis, a publisher’s daughter. He and Delphine would have two sons and one daughter. In the same year, he rented out the Golden Pheasant’s building, and went to Paris to manage a catering firm called “La Maison Chevet” located in the Palais Royal; the firm looked after the great banquets held at the Palace. He then worked for Monsieur Paillard at “Restaurant Maire.”

Teams up with César Ritz

In 1884, he moved to Monte Carlo to work there at the Grand Hotel, newly opened by César Ritz. His title was “Directeur de Cuisine.” During the ensuing summers, he worked in Lucerne, Switzerland at the Hotel National. Opened in 1870, and purpose-built as a hotel, the Hotel National was considered the hotel to be at during the summer in Europe.

In 1890, he followed Ritz to London, to help at the Savoy Hotel as Head of Restaurant Services (Delphine and the three children stayed in Monte Carlo.) The Savoy had been opened the previous year, 1889, by Richard D’Oyley Carte, an opera producer, but was losing money. Ritz and Escoffier did a re-opening of the hotel in 1890. At the time, women didn’t dine out in public places in the Anglo-Saxon world, only men did. Escoffier changed that at the Savoy.

By now, Escoffier had his own team of trusted workers, and he insisted on contracts that allowed he and his team to work other places for 6 months of the year. He and his team went on to Rome, where he oversaw the opening of the “Grand Hotel” there.

In 1896 the duo opened their own company called the “Ritz Hotel Development Company”, which drew on Escoffier’s team to help get grand hotels off the ground.

In 1897, Escoffier and Ritz resigned from the Savoy owing to tensions with the board, and D’Oyley Carte’s wife. The board presumably objected to what they saw was a conflict of interest.

The Savoy was able to recruit another chef to manage its kitchens:

“The recent changes at the Savoy Hotel, which have occasioned so much remark, have led to the engagement by the management of the famous chef, Joseph, who has, for a while, deserted his own restaurant in the Rue Marivaux to direct the cuisine of the Savoy. It is a clever move on the part of the directors, since the culinary prestige of the house, which was likely to have been severely prejudiced by the sudden disorganisation, may now be considered as saved.” [3]Hayward, Abraham. The Art of Dining; or, Gastronomy and Gastronomers. In: The Epicure. Issue 53, Vol. V. April 1898. Page 183.

Escoffier used the freed-up time from the Savoy to oversee preparations for the opening of Ritz Hotel in Paris in the place Vendôme that year.

In 1898, Escoffier returned to London to oversee the opening of the Carlton Hotel in London by their company, which was to take much business away from the Savoy.

Carlton Hotel, London. Demolish 1958. Leonard Bentley / flickr / 2011 / CC BY-SA 2.0

In 1902, Ritz had a nervous breakdown and Escoffier along with Ritz’s wife had to take over much of the Carlton Hotel management.

In 1904, Escoffier was asked by the Hamburg-Amerika ship line to plan the kitchens for a new ship, the Amerika.

“Auguste’s next highlight resulted from his being commissioned by a German shipping company, the Hamburg-Amerika Line, to plan, staff and organize the kitchen and restaurant on their new de luxe liner, Amerika…..” [4]James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. p. 195.

As part of his involvement, he even cooked for German Kaiser Wilhelm II on board.

“The Kaiser came aboard at seven o’clock in the evening with his suite having just returned from Kiel where he had been watching a regatta. He had scarcely sat at the table when one of his aides said to him, “Your Majesty sent for Escoffier from London. Is Your Majesty aware that he was a prisoner of war in 1870 and he could be planning to poison us?

I was immediately warned of this observation which could have had quite unpleasant consequences for me. A few minutes later an enormous fellow came to the kitchen to ‘cast an eye over the place’, he said. It certainly was not the object of his visit as he immediately asked me whether it was true I’d been a prisoner of war in 1870. I told him that I had been a prisoner in the camp at Mayence but that I wasn’t on board to poison them. I went on to say that if one day there was trouble again between his country and France, if I was still able, I might do my duty. Meanwhile they shouldn’t worry, as that would upset their digestion.”

After dinner, the Kaiser went to the kitchen and Auguste received him ‘with all the honours due to his rank.’ The Kaiser was very friendly and put Auguste at his ease so that he was able to reply to questions without embarrassment. They then went on to talk about cooking. Auguste learned that the Kaiser favoured an English-type breakfast: coffee, tea, cream; eggs and bacon, kidneys, chops, various steaks, grilled fish, fruit. At dinner, light dishes were preferred so that a full stomach did not discourage spirited conversation. The Kaiser left for bed at about ten o’clock.” [5]James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. pp 195 – 197.

This was to be just the first time that Escoffier met the Kaiser: “The next morning after breakfast he went ashore to go back to Berlin. Auguste wished him bon voyage and the Kaiser shook hands with him saying, “Au revoir et à bientôt.” And indeed they did meet again.” [6]James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. p. 197. On one subsequent occasion, the Kaiser would entrust Escoffier with a menu for a private dinner between the Kaiser, and an actress.

In 1907, Escoffier’s son Paul launched a line of commercially-bottled pickles and sauces under the company name of A. Escoffier Ltd, which were a success.

In the summer of 1914, Escoffier was 67 when the First World War broke out. He carried on at the Carlton during the entire war. The first thing he did the instant war broke out was stock provisions for the hotel’s kitchen, remembering the food shortages of the 1870 war. His kitchen staff was reduced by a third, as men went off to war and women went off to munitions factories. The first shortage his restaurant faced was meat and poultry. But Escoffier considered flexibility and adaptability the sign of a true chef. He switched to promoting venison, which was not rationed, braising it to make it tender. Fish was not rationed, but some types became hard to get, so he switched from using sole to the flat fish called “dab”, and to get the 40-odd salmon his restaurant required daily, he bypassed all the middle men and arranged direct buying deals with Irish and Scottish fishermen.

His son Paul joined the British Expeditionary Force’s canteens, and eventually ran the officers’ club in Boulogne. Paul had been running Escoffier’s side business, A. Escoffier. Without Paul to run it, Escoffier found he couldn’t keep it up. He sold some aspects of the business, but kept control of the brand name Escoffier.

Aside from that, the war in London was largely uneventful for Escoffier; it was just a constant struggle during those years for staff and adequate food supplies for the restaurant. He had to play “camp counsellor” over and over again for cooks under him who said that cooking haute cuisine was impossible under the circumstances.

On Armistice Day, 11 November 1918, 712 people booked to have dinner that night at the Carlton. That the war had ended officially a few hours before did not instantly change Escoffier’s food supplies for later that day. For that night, he invented a dish called “Mignonettes d’agneau Sainte-Alliance”, small patties made from lamb, veal, pork and some chicken, ground and mixed with tinned foie gras, breadcrumbs and some chopped truffle to make the meat go further.

In November 1919, the French President Raymond Poincaré was in London. Poincaré held a ceremony on 11 November 1919 to vest awards on some French people living in London, and surprised Escoffier by presenting him with the Chevalier de la Légion d’Honneur, making him the first chef ever to receive this award.

Final years

When he was 73 years old, in 1919 or 1920, Escoffier retired and left London to return to Monte Carlo where his wife and children had been based all those years.

A 1928 banquet in honour of Auguste Escoffier (foreground left), shown with French Prime Minister Édouard Herriot (right). wikimedia / 1928 / Public Domain

He died in Monte Carlo at the age of 89 on 12 February 1935 at his home at 8 bis avenue de la Costa, just 16 days after his wife had Delphine died, and was buried at Villeneuve-Loubet.

In 1966, the house he was born in at Villeneuve-Loubet was made into a Culinary Art Museum, an initiative spearheaded by Joseph Donon, one of his former underlings.

His memoirs were first published in 1985 in French.

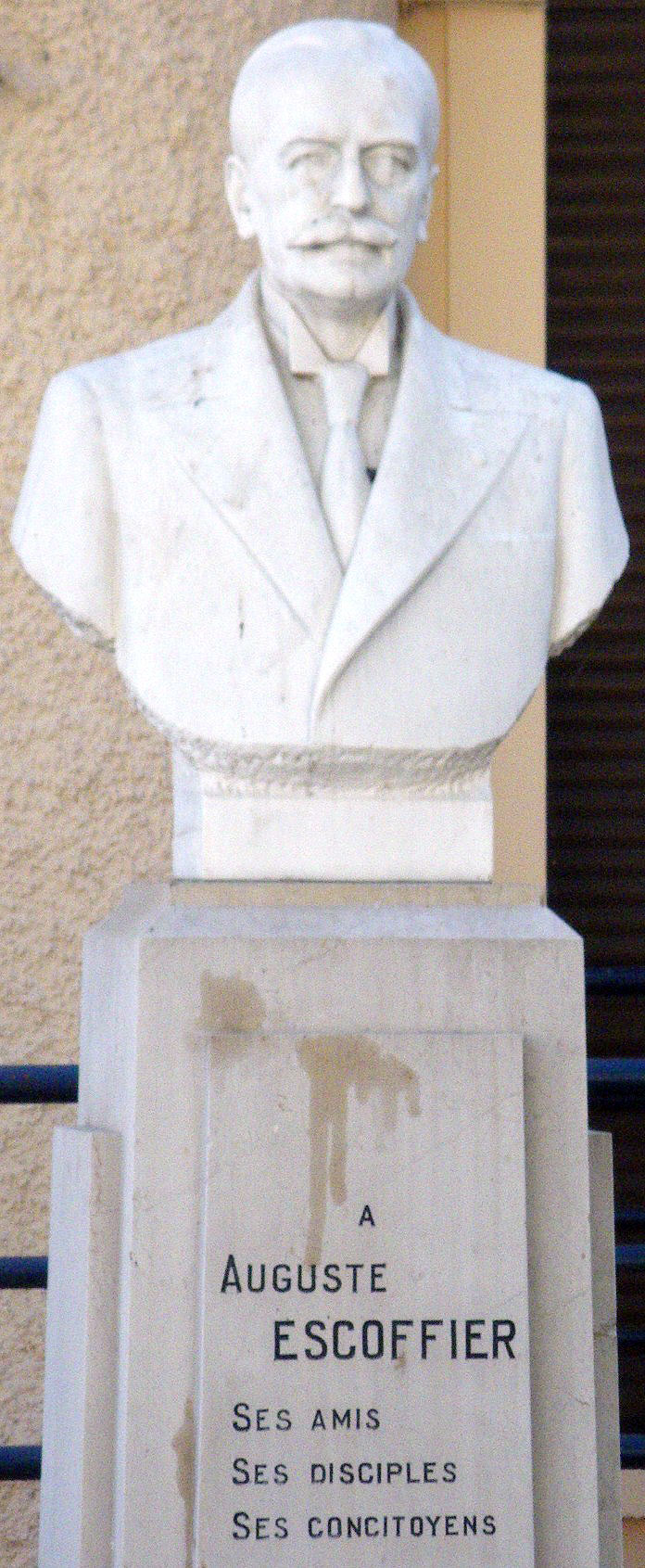

Bust of at Villeneuve-Loubet. The inscription reads, “Il fut le grand ambassadeur de la cuisine française – né le 28 octobre 1846 à Villeneuve-Loubet décédé le 12 février 1935 en principauté de Monaco.”

Books by Georges-Auguste Escoffier

- 1884 — onwards. Wrote for a magazine called “La Revue de l’Art Culinaire”

- 1885 — Traité sur l’art de travailler les fleurs en cire. (with his wife, Delphine Daffis)

- 1903 — Le guide culinaire (with Philéas Gilbert and Emile Fetu)

- 1910 — Projet d’Assistance Mutuelle pour l’Extinction du Paupérisme

- 1911 to 1914 — Founded and put out a monthly magazine called “Les Carnets d’Epicure”

- 1912 — Le livre des menus

- 1927 — Le Riz

- 1929 — La Morue

- 1934 — Ma cuisine, traité de cuisine familiale

Videos

Michel Roux on Escoffier

Auguste Escoffier Foundation & Museum

Sources

Ashburner, F. “Escoffier, Georges Auguste (1846–1935)”, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/50441, accessed 12 Nov 2005.

James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. New York: International Publishing Group. 2006. pp 249 – 253.

References

| ↑1 | James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. London: Hambledon and London. 2002. p. 4. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. p. 205. |

| ↑3 | Hayward, Abraham. The Art of Dining; or, Gastronomy and Gastronomers. In: The Epicure. Issue 53, Vol. V. April 1898. Page 183. |

| ↑4 | James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. p. 195. |

| ↑5 | James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. pp 195 – 197. |

| ↑6 | James, Kenneth. Escoffier: The King of Chefs. p. 197. |