Hermitage Restaurant, date unknown / Public Domain

The Hermitage Restaurant (“Эрмитаж” in Russian) was a famous restaurant in Moscow, operating for 53 years, from 1864 to 1917.

See also: Lucien Olivier, Russian Salad, Russian Service, À la Russe, Elena Molokhovets

About the Hermitage

The Hermitage Restaurant was located in a building, which is still extant, at the corner of Petrovsky Boulevard and Neglinnoj Street on Trubnaya Square (Trubnaya Ploshchad.) Since 1989, the building has housed the Moscow School of Modern Drama Theatre (“Школа современной пьесы”). [1]Moscow Theatre «School of Modern Drama» (Moscow). Accessed January 2022 at http://worldwalk.info/en/catalog/556/ The building is much larger than it seems at the front, with side wings and very large rear court grounds.

The restaurant’s specialty was French cuisine, though adaptations were made of course to local customs. Waiters, for example, dressed in Moscow style — shirts with silk sashes tied at the waist. And as was also Moscow custom, the waiters were not paid. Instead, their tips were their wages. Tips were to be pooled together each day, then divvied up. If anyone held back on the tips, they were dismissed.

“But it would only be after five years of obscure labour that he received the insignia of his profession: a silk sash and a purse of black patent leather for his counters. He always kept the purse in his sash; as for the counters, he was given them at the cash-desk every morning, to the value of twenty-five roubles, and they served to pay for the dishes ordered at the ‘buffet’. Thereafter he would exchange the money he received from customers for further counters. Tips were put into a pool and at the end of the day were shared by the staff. They were paid no wages and even had to pay their employer up to 20 per cent of their earnings…” — Troyat, Henri. Daily life in Russia under the last Tsar. Stanford University Press, 1979. Page 55.

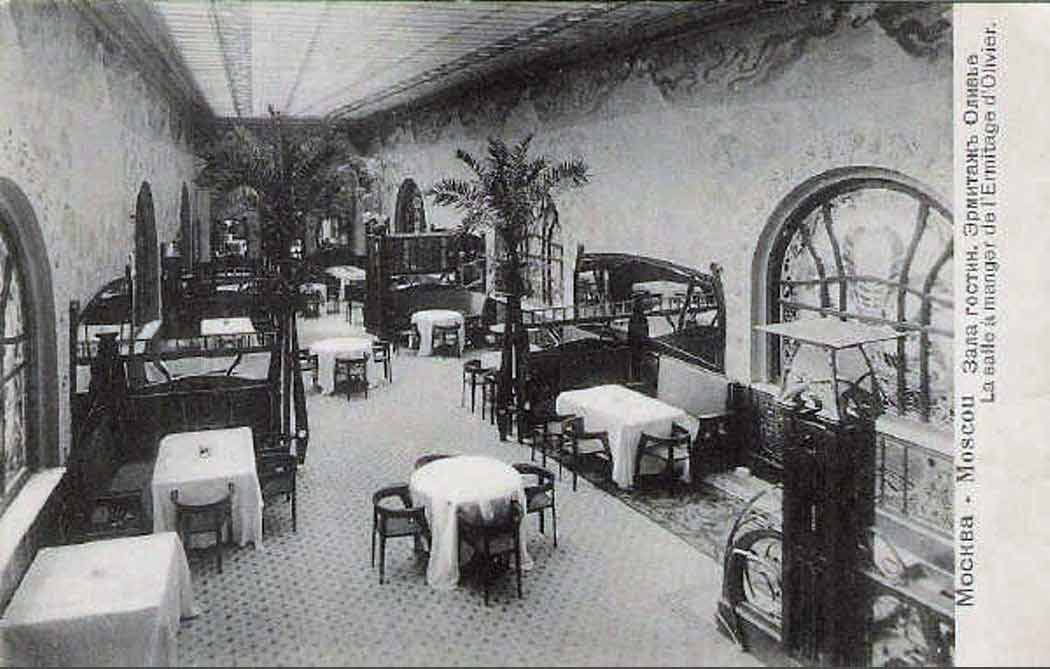

Hermitage Restaurant Lobby / Public Domain

Guests dined “off Saxon dinner services with their hands: ducks from Rouen in France, red partridges from Switzerland, salted fish from the Mediterranean… Calville apples, each with its own coat of arms, costing five roubles apiece…” [2]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 95.

The restaurant was particularly popular for after-theatre or after-ballet suppers:

“Specially famous were the late supper meals which people who were celebrating would come to after the theatre… The rooms were filled with men in tails, dinner jackets or uniforms and ladies with décolleté dresses sparkling with diamonds. The orchestra resounded on the balcony while champagne flowed abundantly.” [3]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 95.

The signature dish of the restaurant was, reputedly, Salade Olivier, or as it came to be called in the West, Russian Salad.

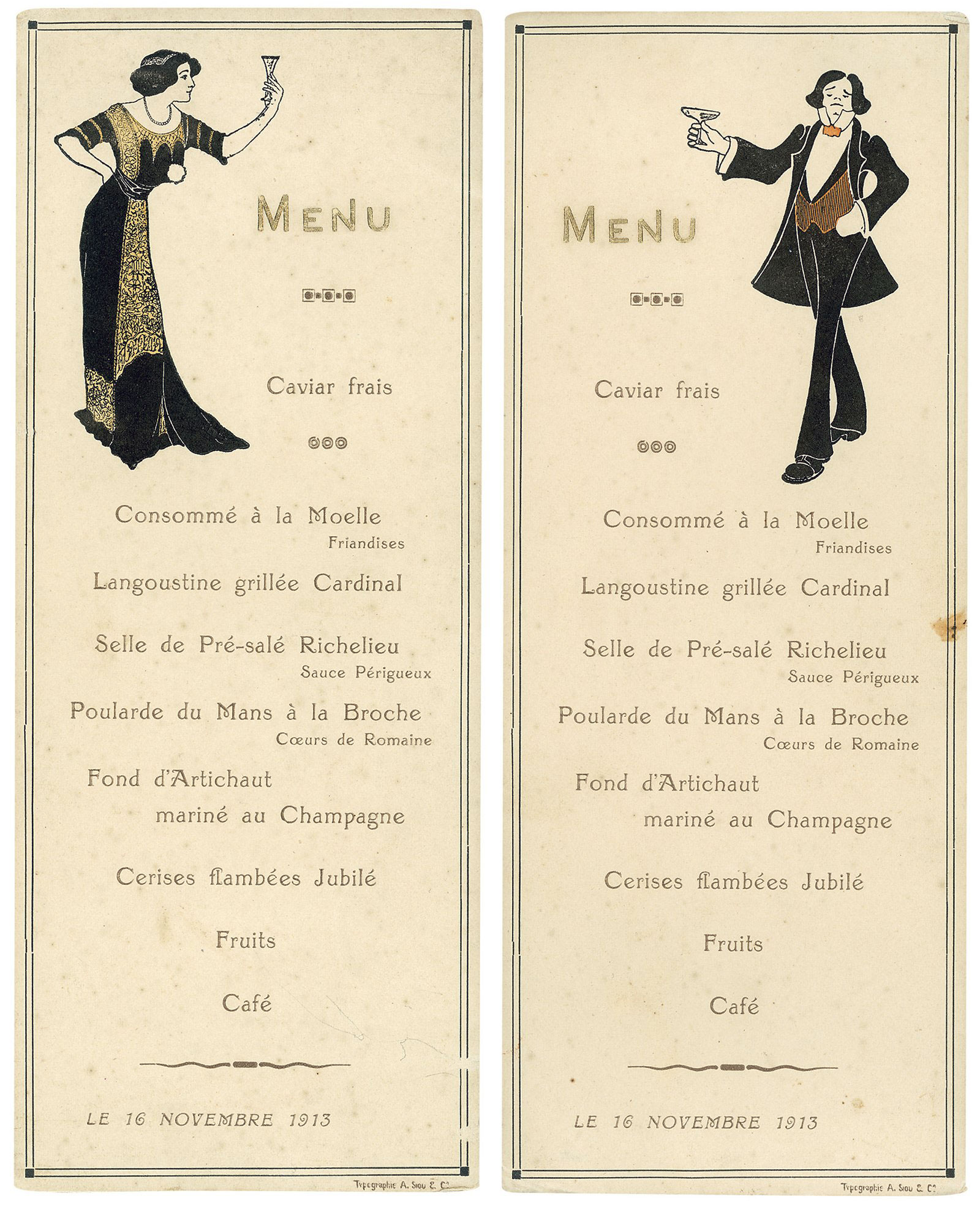

Hermitage Restaurant Menu for 16 November 1913 / Public Domain . Though there is a ladies’ menu and a men’s menu, the listings are identical. Some speculate that the difference may have been in the presentation.

Notable Events at the Hermitage

In the 1870s, a tradition started at the restaurant of letting students celebrate Saint Tatyana’s Day there every 12th January (in the Julian calendar). For a day, the fine furnishings, carpets and good dishes were whisked away and replaced with wooden tables and benches, and sawdust on the floor, for a drinking bash.

18 July 1877 — The composer, Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840 – 1893) married Antonina Miliukova, and held here his wedding celebrations [Ed. The celebration phase of the wedding proved to be short-lived.]

6 March 1879 — A celebration dinner was held for the novelist Ivan Turgenev (1818 – 1883) at the Hermitage [Ed: perhaps to celebrate the news that Oxford was awarding him an Honorary Doctorate]

1880 — Celebratory dinner held for Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821 – 1881)

1899 — Pushkin’s centenary celebration: “In 1899 all the famous writers of the time gathered there for a dinner given to celebrate Pushkin’s centenary” [4]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 95.

1902 — Maxim Gorky (1868 – 1936) held a party here on opening night for the cast of his play “The Lower Depths”

1905 — A famous speech denouncing the current Russo-Japanese war was given at the restaurant [5]The War Futile — 22 February 1905. St Petersburg. “M. Dantchenko, a famous Russian war correspondent and a friend of Gen. Kuropatkin, has made a sensational speech in the Hermitage Restaurant in Moscow. He denounces the war as futile, benefiting the Aristocracy only, and says it means ruin to Russia.” — The Gleaner. Kingston, Jamaica. 24 February 1905. Page 13.

Banquet in the restaurant “Hermitage”. Walnut room. 1907. Iskra Magazine No. 28, 1907 / Public Domain. The guest of honour was Prince Scipione Borghese (1871 – 1927), left foreground in light suit, leaning forward. He was a car lover and racer. #2 in the photo behind him is his chauffeur.

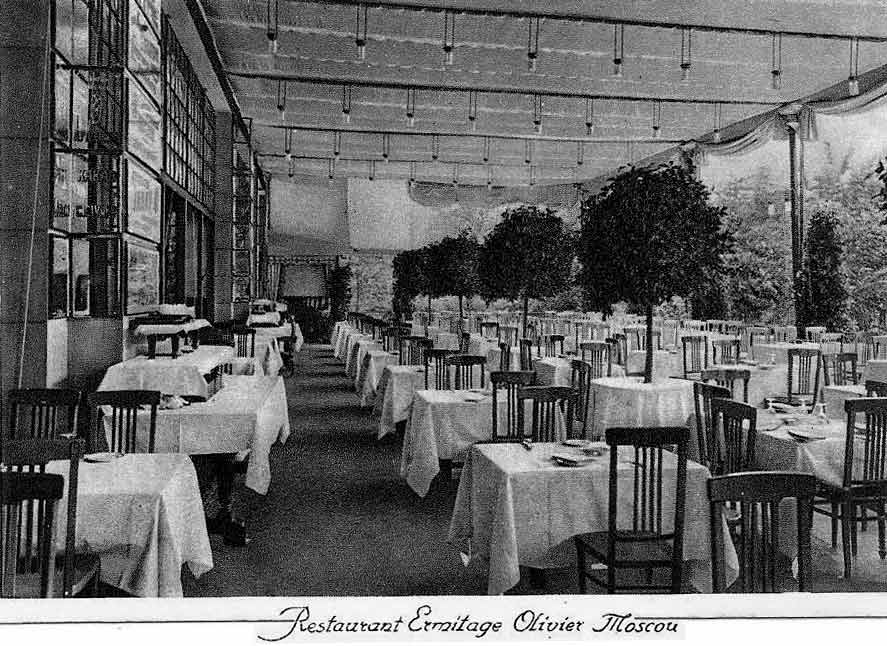

Hermitage Restaurant, a dining area. C. 1900-1910 / Public Domain

History

The restaurant was opened by Yakov Pegov (aka J. A. Pegovym), and Lucien Olivier. The partnership appeared to work well. Yakov was a merchant; Lucien was a French-trained chef. The two had been casual acquaintances before, reputedly meeting by chance at a tobacconist in Trubnaya Square where they both got their supplies of Bergamot tobacco. [6]Timokhina, Elena. Petrovsky Boulevard. Retrieved December 2009 from http://www.guideinmoscow.com/site.xp/051050048.html

They decided to open a fine-dining restaurant together, purchasing a building right on Trubnaya Square. They had the existing building on the site, which dated from 1816 [7]Moscow Mayor Official Website. Turgenev and Gilyarovsky’s favourite place: Menu of the legendary Hermitage Restaurant. 21 November 2018. Accessed January 2022 at https://www.mos.ru/en/news/item/47810073/, remodelled for them by the architect named M. N. Chichagovym (aka Chichagov.)

“At the police box on Trubnaya Square two devotees of the occupant’s bergamot snuff often met up, namely Olivier and one of the Pegov brothers, who would come out every day from his rich house on Gnezdikovsky Lane to get his favourite bergamot mixture; he used to buy just one copeck’s worth, so that it was always freshly made. It was there that Olivier and he came to an agreement by which Pegov bought from Popov all his huge expanse of wasteland, some four acres. In the place where police boxes and Afonkin’s Tavern had stood, on Pegov’s land Olivier’s Hermitage Restaurant rose up, and the square and streets, hitherto inaccessible to wheeled traffic, were paved. In an area where the swamp used to be filled with the croaking of frogs and where we could hear shouts from the regulars of the drinking dens, who had been robbed, there shone the windows of this palace of gluttony, before which, night and day there now stood the expensive carriages of aristocrats, sometimes still carrying liveried outriders.” [8]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 92.

The restaurant opened in 1864. [9]Mikhailova, Olga. Who Needs a House Like This? Retrieved December 2009 from http://www.passportmagazine.ru/article/1559/

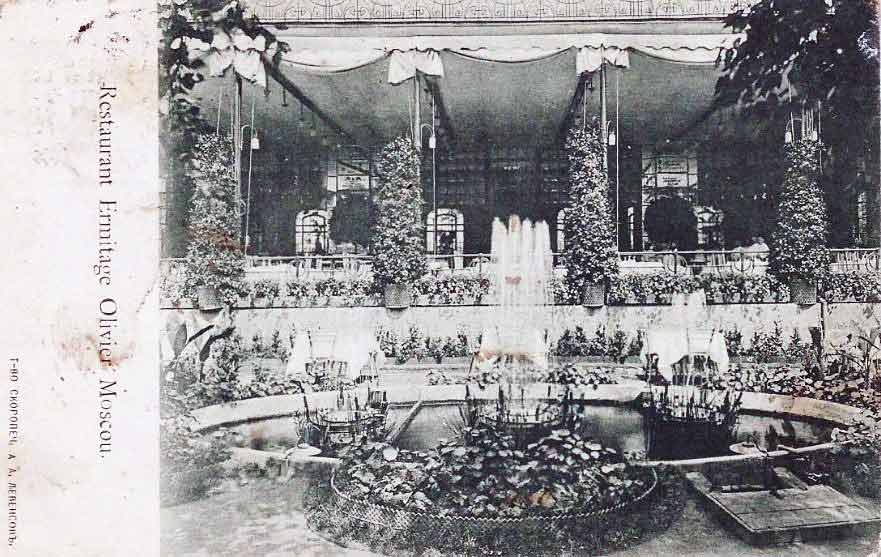

Hermitage Restaurant Garden, c. 1905-1910. / Public Domain

The clientele for the first few decades were the land-owning Russian aristocracy, newly flush with money to spend:

“The first half of the 1860s saw the start of Moscow’s tremendous growth with landowners streaming in from distant corners to spend the money they had received for liberating their serfs. The men who owned the big luxury fashion shops and the best taverns were flourishing, but all the same these latter could not satisfy the refined tastes of the gentry, who had already spent some time abroad – live sturgeon and fresh caviar were not enough for them. .” [10]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 92.

Back summer garden of the Hermitage Restaurant, circa 1900 – 1912. Postcard. / Public Domain

Olivier was already a chef to them. Some of the aristocrats had previously engaged him to come in to cook special dinners for them, in order to impress their fellow dinners with gourmet, non-Russian food:

“Distinguished magnates gave feasts in their private houses in the city; they would order pâté de foie gras from Strasbourg, oysters, lobsters and fiendishly expensive wines from abroad. It was considered particularly smart to have the dinner prepared by the French chef Olivier.” [11]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92.

The restaurant was a success with its target market, the aristocratic social elites:

“Straightaway all this was amazingly successful. The nobility flocked into the new French restaurant, because, besides the general dining halls and little private rooms, there was the great white hall with its columns where one could order just the same meals as those which Olivier made for grandees in their private houses. Furthermore, for these dinners delicacies were brought in from abroad and the best drinks, with the assurance that the brandy came from the cellars of Louis the Sixteenth’s palace and bore the inscription of the Trianon. It was the spoilt aristocrats who rushed to partake of these delicacies, not knowing otherwise what to do with their money… This was the first, aristocratic period of the Hermitage.” [12]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92.

Back garden of the Hermitage Restaurant, circa 1910 – 1912. Postcard posted by a A. A. Levenson in October 1912. / Public Domain

While Olivier helped manage the business as a whole, a famous chef from Paris, Léon Duguet, was recruited to actually run the kitchen:

“The whole business was managed by three Frenchmen. Olivier had the general oversight, Marius looked after special guests, and the kitchen was supervised by the famous man from Paris, the chef Léon Duguet. ” [13]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92.

Olivier died in 1883, still in his mid 40s. The restaurant carried on successfully, and in the 1890s, the clientele began transition to the rising wealthy merchant upper-classes:

“Things went on like this until the start of the 1890s. Until then the old aristocracy had fought shy of upstarts from the world of business and civil servants. People from that class used to eat in separate private rooms. Then the spendthrift aristocracy began to die out. Now the first to appear in the large hall were representatives of Moscow’s foreign community… They came straight from the Stock Exchange, stiff and stern, each company occupying its own table. After then came Russian merchants, who had just exchanged their traditional sibirka coats and barge-hauler boots for smart smoking jackets and now mixed with the representatives of foreign firms in the halls of the Hermitage. Olivier had gone. Marius, who had been so reverential when faced with exalted gourmands, was now serving merchants as well, but he talked with them casually, even condescendingly. The cook Duguet was no longer thinking up delicacies for these merchants, and in the end he went back to France. But things were still fine as they were… usually it was here that the richest merchants’ weddings were celebrated with

hundreds of guests… The White Hall was hired particularly often by Moscow’s foreign business community for banquets in honour of their fellow countrymen who had arrived on a visit.” [14]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92.

Hermitage Restaurant c. 1899-1900. Альберт Иванович Мей (1842-1913) / 1902 / Public Domain

Sometime after 1904 [15]It appears to have been after the start of the Russo-Japanese War, the restaurant was acquired by new owners, but instead of things going downhill, as is sometimes the case, it went on to greater splendours:

“The Hermitage was transferred to the ownership of a trading company. New directors replaced Olivier and Marius: Polikarpov, the furniture maker, Mochalov, the fish merchant, Dmitriyev, the restaurateur, Yudin the merchant. Astute people, typical of the new public. The first thing they did was to rebuild the Hermitage and make it even more luxurious, providing chic individual bathhouses in the same building and adding a new wing with meeting rooms. The Hermitage began to make huge profits — with drunkenness and debauchery… The “distinguished” Moscow merchants and less prominent rich men used to go straight into their private rooms, where they could immediately unwind. Fresh caviar was served in silver buckets. For fish soup they brought in sturgeon over two feet long straight into the rooms where they speared them. And yet they ate asparagus straight off the knife and used their knife to cut up artichokes. Of these private rooms the red one was particularly famous; it was there that Moscow’s fast set ate the clown Tanti’s trained pig… Specially famous were the late supper meals which people who were celebrating would come to after the theatre… The rooms were filled with men in tails, dinner jackets or uniforms and ladies with décolleté dresses sparkling with diamonds. The orchestra resounded on the balcony while champagne flowed abundantly. The private rooms were crammed with people. The meeting rooms did a roaring trade! For a few hours they might be paying from five to twenty-five roubles… Anyone who was anybody was there… [16]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir.Page 94.

Al Fresco dining at the Hermitage Restaurant, circa 1890 – 1910. / Public Domain

After The Russian Revolution

The restaurant closed in 1917 during the Russian Revolution.

In 1921 to 1922, the building was used by the American Relief Administration (A.R.A) to feed people during a two-year relief programme when Russia slid into famine. [17]Patenaude, Betrand M. The Big Show in Bololand. Stanford University: Hoover Digest. No 4. 2002.

“In the A.R.A. Moscow. Women of noble families, shopkeepers wives, manufacturers wives and peasant women sewed side by side for weeks in the warm rooms of the Hermitage Restaurant, formerly Moscow’s gayest and fastest cafe, now central children’s feeding depot for the A.R.A., making little knitted things for the children…” [18]Hullenger, Edwin W. America Santa to Russia’s Children. Moberly Evening Democrat. Moberly, Missouri. 1 February 1922. Page 3.

The building was used as is; relief workers toiled amongst the opulent splendour in which Russian aristocrats and business magnates had formerly partied:

“Moscow’s Most Noted Restaurant Now American Kitchen for Children: The crystal chandeliers are still hanging. The exquisite murals of 1885 still adorn the ceilings. The green and gold walls have not changed. Even the huge stoves in the kitchen are the same. But the guests are entirely different. To world travelers familiar with the gay Hermitage Restaurant of Moscow and the brilliant parties that were once held in that lively Russian city, the present diners at the Hermitage would present an incongruous picture. Instead of men and women in evening dress and satin, velvet and ermine entering the great doorways, each night after the opera or ballet, he would see a noon-day procession of small boys and girls, carrying pails, cups, coffee-pots, or bowls.” [19]Mexia Evening News. Mexia, Texas. 1 May 1922. Page 8.

From 1921 to 1928, the Russian revolutionary government Lenin experimented with limited capitalism under a policy called The New Economic Policy. During this time, sometime after 1922 when the American Relief efforts were finished with the building, someone did an attempted re-opening of the restaurant, but it was of course a shadow of its former self:

“The man who used to run the restaurant managed to mimic the restaurant’s past in a tawdry sort of way. The menu was showing again Escalopes à la Pompadour, Escalopes Marie Louise, Valois sauce, Olivier salad. However, the cutlets were tough, having been cooked in castor oil and the Olivier salad was made from leftovers. All the same this suited the NEPmen [20]NEPmen were people able to profit from the fleeing New Economic Policy customers very well. In the porter’s lodge were hanging sealskin coats, beaver collars, sable coats. In the main hall were those same chandeliers, white tablecloths and gleaming crockery… On the wall facing the buffet they had still kept something written by M.P. Sadovsky. He used to take his lunch here, mocking the fast set and watching the various characters. Instead of being served by waiters in white shirts, the food was now served by menials in soiled jackets, and they would run when they were called, the trimmings on their trousers gleaming like lace.” [21]Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 95.

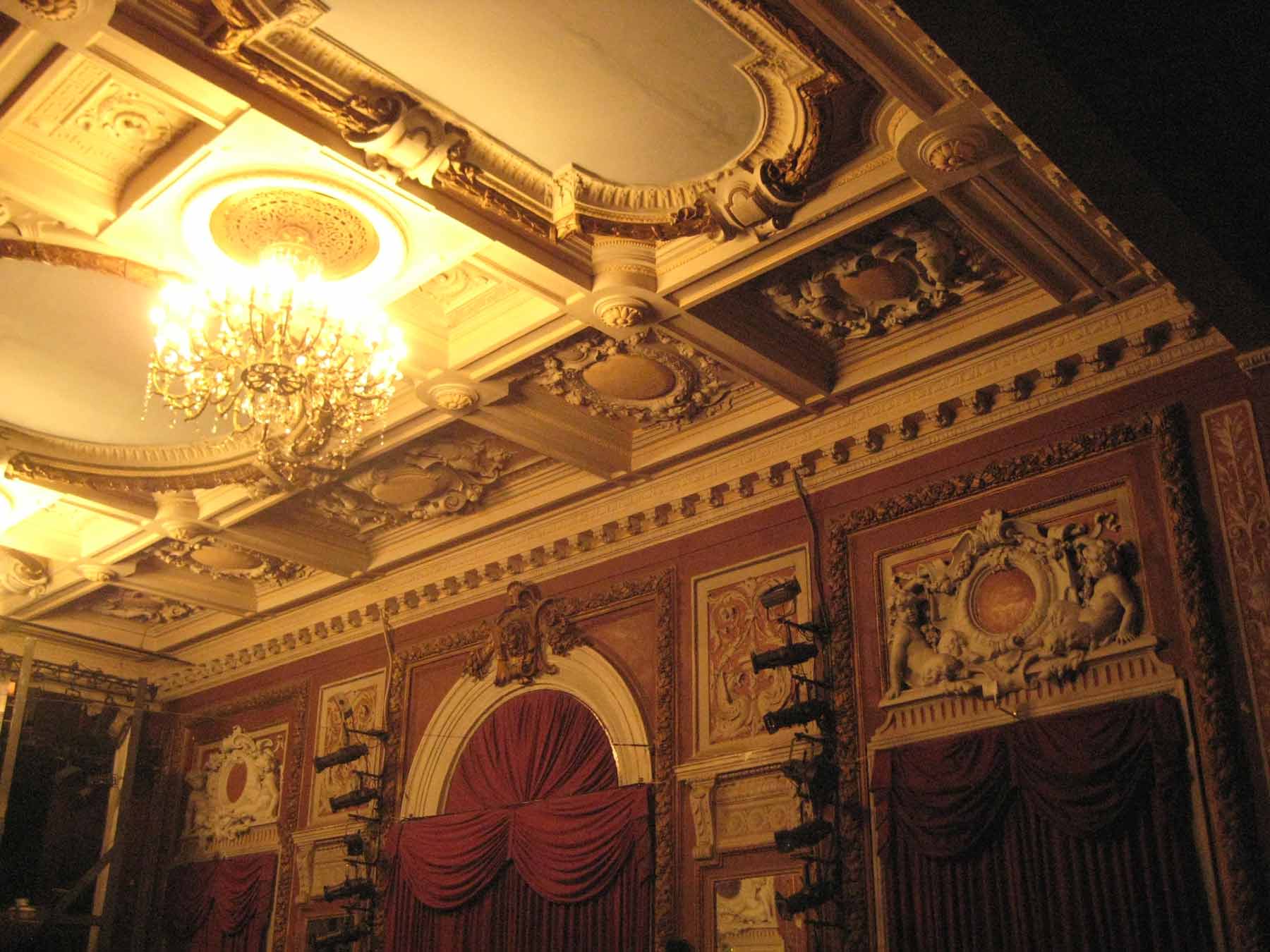

Hermitage Restaurant, surviving interior detailing. Shakko / wikimedia / 2011 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The revival attempt does not seem to have lasted long. By 1924, the building had been taken over by Moscow City Council and renamed to “дом крестьянина”: The House of the Peasant. [22]”The former Hermitage is now the House of the Peasant and the Proletkule.” — Tsivian, Yuri, Ed. Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties. Sacile, Pordenone, Italy: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. 2004. Page 177. [23]By 1924, furniture made for the Moscow House of the Peasant was featured in the magazine “Art and Industry” 1924, Issue 2. As noted in: Lavrentiev, Alexander. “Experimental Furniture Design in the 1920s.” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, vol. 11, Florida International University Board of Trustees on behalf of The Wolfsonian-FIU, 1989, p 143, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1503987.

Peasant House, c. 1936. / Public Domain

After World War Two [24]Moscow Mayor Official Website., the building housed a publishing firm, “Vysshaya Shkola” (Высшая школа) [25]Dedushkin, Alexey . Salad “Olivier” or “Coachman, drive to the Yar”. Blog entry. Accessed January 2022 at https://www.moskvahod.ru/blog/test/ , and then eventually the present day theatre school.

Hermitage Restaurant today street view. Theatre school. sa77 / wikimapia / 2021 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Hermitage Restaurant today street view. Nikolai Gvozdev / wikimapia / 2012 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Other Hermitage Restaurants

Restaurants named Hermitage have been in Monte Carlo (opened 1899) [26] “Then there is the fashionable Grand, where no fewer than seven kings or princes of the blood have been seen dining at one time at different tables; and the Hermitage, which is the newest and quite the prettiest restaurant, and which is always full. There is a rumour that M. Ritz, who organised the Grand, and M. Benoist, who started the Hermitage, mean amalgamation, which would be a most popular move, as they adjoin each other.” — “Onlooker. Society on the Riviera. Favourite Haunts in Monte Carlo. Middlesex, London: London Daily Mail. 21 March 1899. Page 4. , Cairo [27]”Rioting Egyptian mobs ran wild through Cairo today… as the mobs move on, they smashed plate glass windows, including those in the popular Hermitage restaurant, and in the Immobilia building, where the Associated Press has its offices.” — The Canadian Press. Irate Egyptians cry for revenge as troops move in, quell mobs. Lethbridge, Alberta: The Lethbridge Herald. 26 January 1952. Page 1, and now are all over the United States.

The Hermitage Restaurant now (2009) open in St Petersburg, Russia, shares only the name.

Literature & Lore

“The three famous chefs who left their mark in Russia were Carême, Urban Dubois, and Olivier. The last of these three opened a restaurant called the Hermitage in Moscow in the 1880s [Ed: the date here is incorrect], described by Lesley Chamberlain as ‘one of the great historic restaurants of the world’, and it was there that French-Russian cuisine was most fully elaborated.” — Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 810.

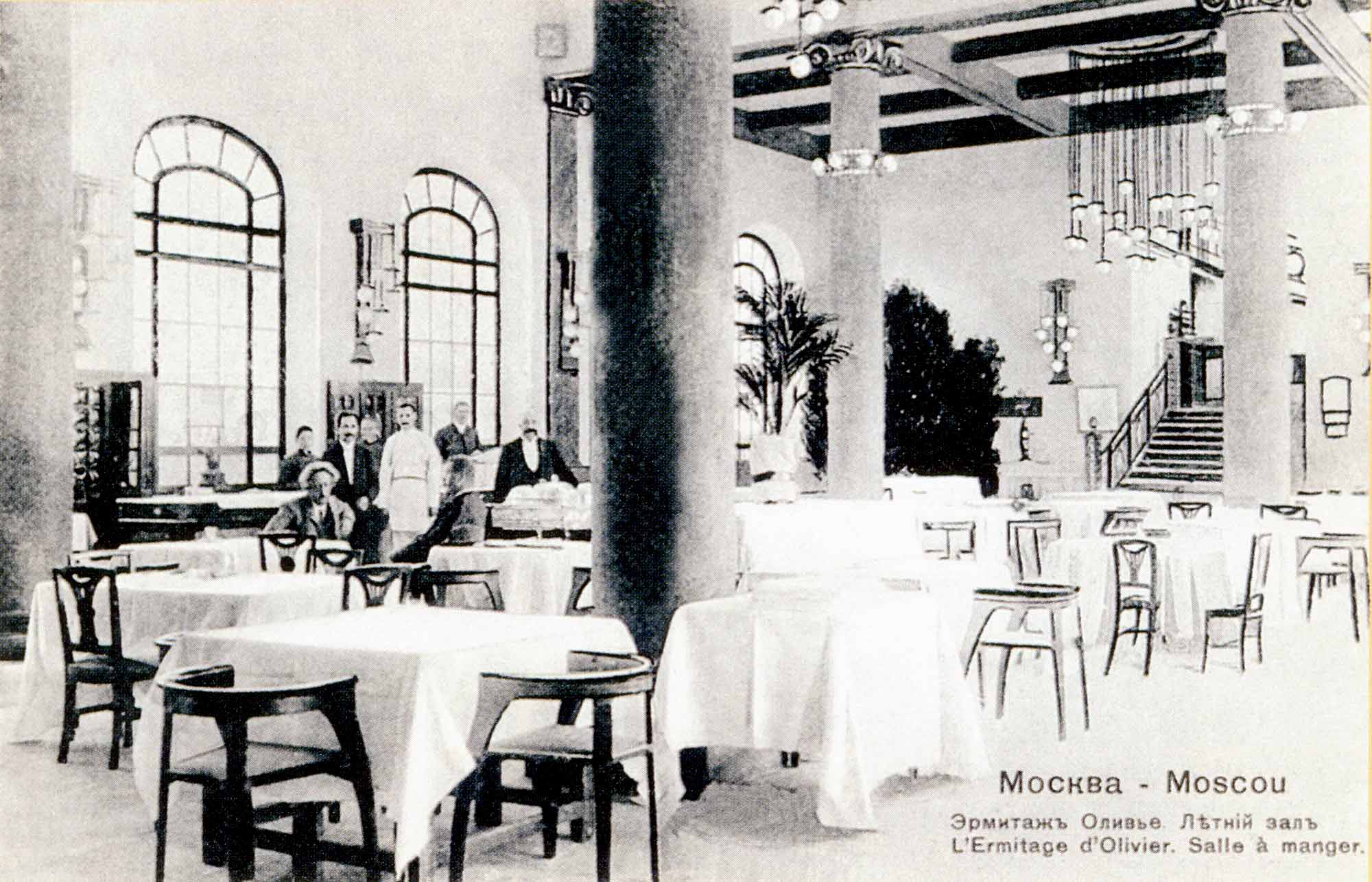

The “Summer Hall” dining room in the Hermitage Restaurant, circa 1902 – 1907. / Public Domain

Sources

Kuper, Andy. Moscow – Trubnaya Street. November 2009. Retrieved December 2009 from http://rebnau.blogspot.com/2009/11/moscow-trubnaya-street.html

References

| ↑1 | Moscow Theatre «School of Modern Drama» (Moscow). Accessed January 2022 at http://worldwalk.info/en/catalog/556/ |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 95. |

| ↑3 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 95. |

| ↑4 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 95. |

| ↑5 | The War Futile — 22 February 1905. St Petersburg. “M. Dantchenko, a famous Russian war correspondent and a friend of Gen. Kuropatkin, has made a sensational speech in the Hermitage Restaurant in Moscow. He denounces the war as futile, benefiting the Aristocracy only, and says it means ruin to Russia.” — The Gleaner. Kingston, Jamaica. 24 February 1905. Page 13. |

| ↑6 | Timokhina, Elena. Petrovsky Boulevard. Retrieved December 2009 from http://www.guideinmoscow.com/site.xp/051050048.html |

| ↑7 | Moscow Mayor Official Website. Turgenev and Gilyarovsky’s favourite place: Menu of the legendary Hermitage Restaurant. 21 November 2018. Accessed January 2022 at https://www.mos.ru/en/news/item/47810073/ |

| ↑8 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 92. |

| ↑9 | Mikhailova, Olga. Who Needs a House Like This? Retrieved December 2009 from http://www.passportmagazine.ru/article/1559/ |

| ↑10 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Memoirs of Old Moscow. Translated by Brian Murphy and Michael Pursglove. 2016. Accessed January 2022 at http://gilyarovsky.com/. Page 92. |

| ↑11 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92. |

| ↑12 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92. |

| ↑13 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92. |

| ↑14 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 92. |

| ↑15 | It appears to have been after the start of the Russo-Japanese War |

| ↑16 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir.Page 94. |

| ↑17 | Patenaude, Betrand M. The Big Show in Bololand. Stanford University: Hoover Digest. No 4. 2002. |

| ↑18 | Hullenger, Edwin W. America Santa to Russia’s Children. Moberly Evening Democrat. Moberly, Missouri. 1 February 1922. Page 3. |

| ↑19 | Mexia Evening News. Mexia, Texas. 1 May 1922. Page 8. |

| ↑20 | NEPmen were people able to profit from the fleeing New Economic Policy |

| ↑21 | Gilyarkovsky, Vladimir. Page 95. |

| ↑22 | ”The former Hermitage is now the House of the Peasant and the Proletkule.” — Tsivian, Yuri, Ed. Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties. Sacile, Pordenone, Italy: Le Giornate del Cinema Muto. 2004. Page 177. |

| ↑23 | By 1924, furniture made for the Moscow House of the Peasant was featured in the magazine “Art and Industry” 1924, Issue 2. As noted in: Lavrentiev, Alexander. “Experimental Furniture Design in the 1920s.” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, vol. 11, Florida International University Board of Trustees on behalf of The Wolfsonian-FIU, 1989, p 143, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1503987. |

| ↑24 | Moscow Mayor Official Website. |

| ↑25 | Dedushkin, Alexey . Salad “Olivier” or “Coachman, drive to the Yar”. Blog entry. Accessed January 2022 at https://www.moskvahod.ru/blog/test/ |

| ↑26 | “Then there is the fashionable Grand, where no fewer than seven kings or princes of the blood have been seen dining at one time at different tables; and the Hermitage, which is the newest and quite the prettiest restaurant, and which is always full. There is a rumour that M. Ritz, who organised the Grand, and M. Benoist, who started the Hermitage, mean amalgamation, which would be a most popular move, as they adjoin each other.” — “Onlooker. Society on the Riviera. Favourite Haunts in Monte Carlo. Middlesex, London: London Daily Mail. 21 March 1899. Page 4. |

| ↑27 | ”Rioting Egyptian mobs ran wild through Cairo today… as the mobs move on, they smashed plate glass windows, including those in the popular Hermitage restaurant, and in the Immobilia building, where the Associated Press has its offices.” — The Canadian Press. Irate Egyptians cry for revenge as troops move in, quell mobs. Lethbridge, Alberta: The Lethbridge Herald. 26 January 1952. Page 1 |