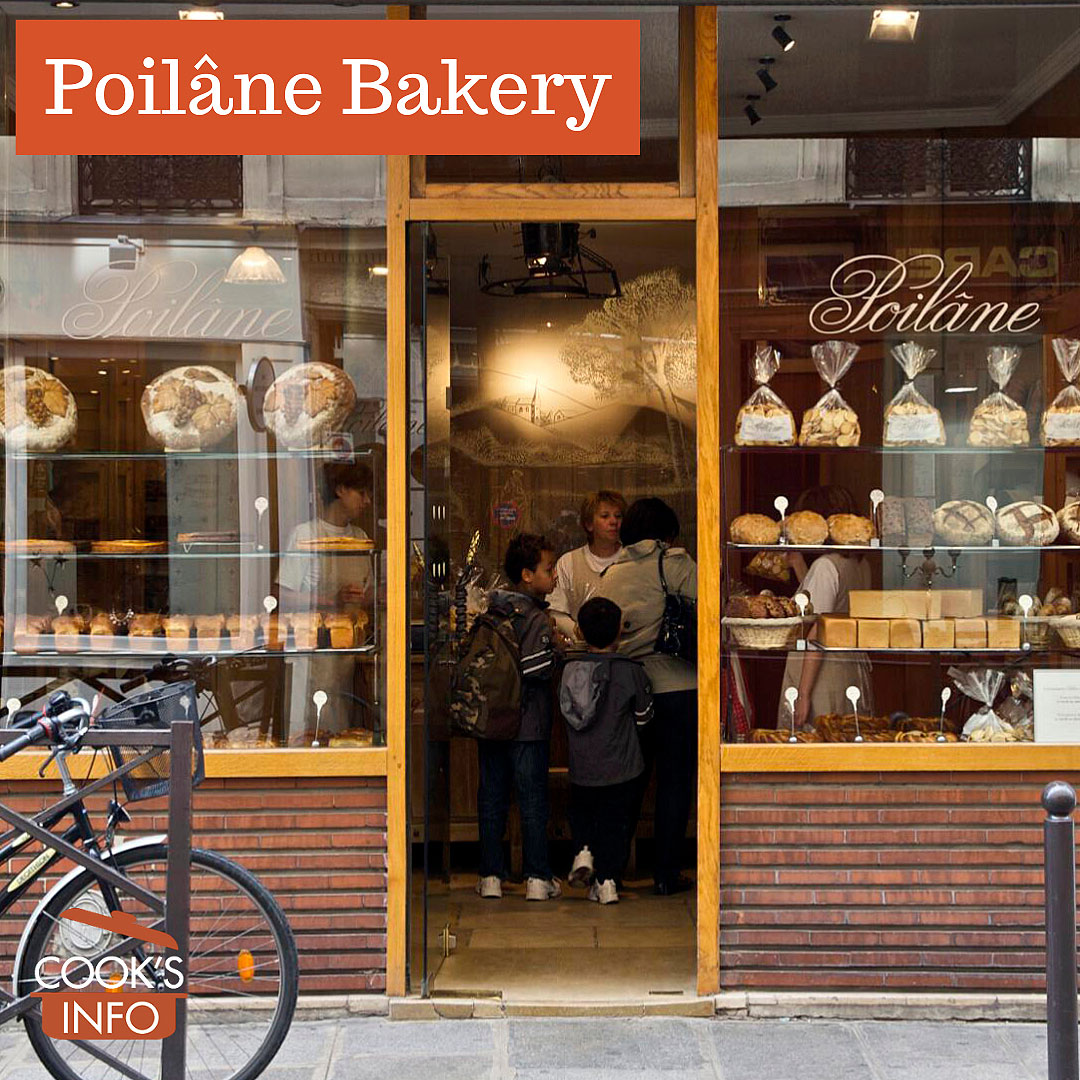

Poilâne, 8 rue du Cherche-Midi, Paris 75006, September 2008. Thor / wikimedia / 2008 / CC BY 2.0

Poilâne (pronounced pwa-LEN) is the name of a privately-owned family bakery company in Paris, France that has become one of the most well-known and prestigious bakeries in the world. It has been in continuous operation since 1932.

Branches of the Poilâne family

There are two different Poilâne family companies operating bakeries: La société Poilâne SA (website: https://www.poilane.com/) , and Max Poilâne SAS (website: https://www.max-poilane.fr/).

As of 2019, the La société Poilâne SA company has “a team of more than 200 men and women who bake and sell 5,000 loaves (and counting) of our breads and baked goods every day.” [1]Poilâne, Apollonia. The Secrets of the World-Famous Bread Bakery. New York: Houghton Mifflin. 2019. Page 18. Its headquarters are still in the building that the bakery first opened in. The current owner (2020) is Apollonia Poilâne, the grand-daughter of the founder.

There are also bakeries operating in the Max Poilâne SAS company, covered in a separate Max Poilâne section.

Unless otherwise specified, Poilâne in the discussion below refers to La société Poilâne SA.

Poilâne breads

Poilâne is perhaps best known for its signature loaf of bread, a round sourdough loaf they call the “miche Poilâne®.” This loaf is so in demand that it is flown around the world daily to over 40 countries. See separate entry on “Pain Poilâne.”

In addition to this bread, Poilâne sells a few other breads such as a rye bread (“pain de seigle Poilâne®”), walnut bread (“Pain aux Noix Poilâne®”), rye and currant bread (“Le pavé aux raisins Poilâne®) and a white sandwich loaf with pepper in it (“Le Poivré Poilâne®”).

They deliberately do not make a wide-range of items. The current owner, Apollonia Poilâne, says:

“I have a very instinctive and simple approach to bread,” she told me. “My philosophy is a small array of breads, each with its own use. I do not believe in making one bread with hazelnuts, one with almonds, and one with cumin, just for the hell of it.” Her other prejudices include breads that contain meats (“doughy and nasty”), breads that contain cheeses (“frivolous”), breads that contain novelty ingredients, such as algae (“not very relevant”), “organic” breads (“I don’t believe in paying money to some guy sitting behind a desk to certify something, when my father and grandfather before me were working very closely with their suppliers to make sure there were as few pesticides as possible”)…” [2]Collins, Lauren. A daughter upholds the traditions of France’s premier baking dynasty. New York: The New Yorker. 26 November 2012.

Despite that, she actually has introduced new products, and new services:

“Whether it is our breads, biscuits or “pâtisseries boulangères” or our services, since 2002, Poilâne has embarked on a journey, exploring grains and fermentation. We’ve created new products—a 100% corn bread, a spoon-shaped biscuit, a range of cakes—new services as technology evolves…. ” [3]Plummer, Todd. Paris’s Most Famous Bakery Spills the Secret to a Perfect Loaf. New York: Vogue Magazine. 28 September 2019.

Pain levain versus pain Poilâne. Rebecca Siegal / flicker / 2010 / CC BY 2.0

Poilâne pastries

Poilâne offers “a handful of pastries that don’t use cream (the others being the preserve of the patisserie).” [4]Rushton, Susie. Apollonia Poilâne. In: The Gentlewoman Magazine. London, England: Fantastic Woman Ltd. Issue n° 4, Autumn & Winter 2011. The limited range includes croissants, punitions (shortbread cookies), shortbread cookies shaped like spoons, apple tartlets and a custard flan [5]Lebovitz, David. Poilâne. Blog posting 1 December 2011. Accessed April 2020 at https://www.davidlebovitz.com/Poilâne-bakery-cuisine-de-bar-paris/

The punitions are a whimsy unique to Poilâne, that recall a part of their family history:

“…sweet biscuits called punitions, named for a game Pierre’s grandmother played with her children, in which she would pretend to dole out ‘punishments’ that turned out to be butter cookies – a game little Lionel is said to have loved.” [6]Rushton, Susie, op. cit.

With each purchase in the shop, you get a complimentary punition cookie, or two, at the till. You can also buy them by the bag.

The basement of Poilâne’s main Paris store at 8, rue du Cherche-Midi, is where the baking happens. There is a separate, cooler room for the assembly of pastries apart from the hot oven room where they are baked: “Meanwhile, in an adjacent room, two or three pastry chefs are at work making cookies and pastries, including croissants, pains au chocolat, and tarts. Thanks to the thick door and the massive refrigerator built into the pastry room’s far wall, it’s much cooler in there, perfect for handling buttery doughs.” [7]Poilâne, Apollonia, op. cit., page 37.

Poilâne stores

As of 2020, Paris stores operating in the La société Poilâne SA company were:

- 8, rue du Cherche-Midi (6th arrondisement)

- 38, rue Debelleyme (3rd arrondisement)

- 49, boulevard de Grenelle in Paris [15th arrondisement]

- 83, rue due Crimée

In the Cherche-Midi store the actual bakery for the store is in the basement. There is just the one oven there, but it can produce up to 70 loaves of bread at once: [8]”the seventy-loaf capacity of the bakery’s single oven…” ibid., page 18.

“A colossal arched brick construction that can bake 70 loaves at a time, it is tended day and night in never-ending shifts by bakers who must wear shorts and T-shirts year-round to bear the unrelenting heat from the burning wood” [9]Rushton, Susie, op. cit.

In London, England, their store is at 49 Elizabeth Street in Belgravia. It has its own ovens.

The company also runs two restaurants serving light lunches. It calls them “Comptoirs Poilâne” (“Poilâne counters”.) The restaurants serve open-faced sandwiches (“tartines”) on Poilâne bread.

As of 2020, these locations are:

- Paris: 8, rue du Cherche-Midi (next to main store)

- 39 Cadogan Gardens, Chelsea

The restaurants were rebranded from their previous name of “Cuisine de bar”. There used to be a second Paris one at 38, rue Debelleyme.

Poilâne bread factory

Poilâne has a large bakery complex in a suburb of Paris, Bièvres, which began operation in 1983. It is a bakery only, with no shop: no products are sold directly to consumers out of here.

A white stucco, miche-shaped building, it was designed by Irena Poilâne, daughter-in-law of the founder of Poilâne.

Apollonia Poilâne writes:

“…my father [Lionel] enlisted my mother, a trained architect, to design a building outside the city where he could continue my grandfather’s artisanal baking methodology on a much larger scale. Together, my parents created a spectacular circular space housing twenty-four wood-burning ovens…” [10]Poilâne, Apollonia, op. cit., page 18.

Lionel called the complex “la Manufacture Poilâne” — the Poilâne ‘manufactory’. “My father chose the name for its Latin roots: manu factus means “hand made.” [11]ibid. [12]Oxford says the term ‘manufactory’ has been around in English since at least 1630, though it is now obsolete: “Servile and manufactory men that should serve the uses of the world in the handicrafts” (Henry Lord, Banians and Persees, 70, 1630). “A sort of idol who did … daily create men by a sort of manufactory operation” (Jonathan Swift, A Tale of a Tub, 1704).” The term in modern times has now been used as well by other bread bakeries, such as the Tartine Bakery in San Francisco (founded 2002.)

“An 18-year veteran of the firm, [Jean] Lapoujade greets me at the circular, spotlessly white ‘manufactory’ in the Paris suburb of Bièvres. The site is the embodiment of Lionel Poilâne’s pet concept of “retro-innovation” – the selective use of modern techniques in the service of traditional baking. But the real innovation here is more in the logistical organization than in mechanization: The only machines at the Bièvres plant are the automatic kneading bins. The rest of the work is done by hand by 60 Poilâne-trained bakers, who work around the clock in three shifts. “What we’re really doing here,” says Lapoujade, “is using artisanal methods to produce bread on a quasi-industrial scale.” [13]Sancton, Tom. Apollonia Poilâne inherits a famous Paris bakery. New York: Fortune Magazine. 19 January 2007.

The bakery factory is divided into twelve bakehouses, with each bakehouse given a different name. “Twelve airy bakehouses—each equipped with two ovens, and named for an important figure in the history of bread—radiate like spokes from the core… [one is] the St. Roch bakehouse, where a plaque commemorate[s] the fourteenth-century ascetic kept alive, according to legend, by a dog that each morning brought him scraps of bread.” [14]Collins, Lauren, op. cit.

Each bakehouse has large windows to let in natural light. Each also has two brick-lined ovens, replicas of the original one in town at 8, rue du Cherche-Midi. This allows two bakers at a time to work in each bakehouse. “Each baker works on his own batches, but he also works in the presence of someone else,”… She pointed to a bank of windows. “He also has daylight.” [15]Collins, Lauren, op. cit.

The ovens run twenty-four hours a day. The ovens don’t have thermometers: the bakers learn how to gauge the correct heat themselves

“…Poilâne opened a new production facility in Bièvres, which is just outside Paris. And this is where Lionel implemented a concept he called retro-innovation, a combination of traditional principles and creative solutions that met the current realities and expectations of Poilâne’s markets. He had figured out how to do big business and still deliver a handcrafted miche – Poilâne’s signature wheel of sourdough bread. Lionel organized the baking teams on the production floor of his new “manufactory” in a sun-ray pattern emanating from a pile of dry cherry wood that stood in the center of the room. Every section was managed by an independent baking team, which orchestrated its production schedule and worked as if it were an independent bakery. Which effectively meant that on a roster of, say, one hundred bakers, no one was at the bottom of the pecking order — you came in no lower than number five on a team made up of your partners in excellence. Lionel also implemented a strict system of quality assessment at the Bièvres bakery. One representative loaf of every batch, identified by the first name of the head baker, was placed on a tray cart and presented for inspection. The loaves were then closely examined, sliced, smelled, and tested for their pH levels.” [16]Martins, Patrick. The Carnivore’s Manifesto: Eating Well, Eating Responsibly, and Eating Meat. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. 2014.

Everyday, twenty-four loaves, one from each oven, tagged with the name of the bakers, is sent to Poilâne at Rue du Cherche-Midi in town for a quality control review at headquarters. “Every morning, Apollonia receives twenty-four loaves of sourdough. Each is labelled with the name of a baker from the Bièvres manufactory. The shipment is Poilâne’s form of quality control. “I just look at the breads and get a sense of the aesthetic of them,” she told me. “This way, even if I haven’t had time to go to the manufactory, I can keep track.” [17]Collins, Lauren, op. cit.

The Bièvres “manufactory” makes the bread sent to supermarkets and restaurants, and shipped around the world. Its location, near to Orly airport, makes it ideally situated. “Lionel was as inspired a businessman as he was an artisan… when he set up a factory at Bièvres, near Versailles… close to a freight airport.” [18]Rushton, Susie, op. cit.

“Starting at 4 A.M. every day, trucks rumble up to the loading dock, then fan out to deliver warm Poilâne loaves to vendors in the Greater Paris region. In the afternoon other trucks will take boxed loaves to Charles de Gaulle airport; from there FedEx planes deliver them overseas within 24 to 48 hours. Cost per FedExed loaf in the U.S.: about $47, compared with $10 [8 euros] in Paris.” [19]Sancton, Tom, op. cit.

The loaves sold in England at Harrods, Harvey Nichols, Partridges and Waitrose are baked and shipped out from here, as are those sold in specialty stores in New York, Los Angeles, Toronto, Japan and Saudi Arabia.

The bread is also sent out to restaurants and retail stores in Paris and around France. [20]Collins, Lauren, op. cit.

[Ed: note that the above video shows bread being Fedexed from the Rue du Cherche-Midi store; most in actuality would be shipped out from the Bièvres bakery instead.]

History

Pierre-Léon Poilâne

The Poilâne bakery first opened in 1932.

The founder, Pierre Léon Adrien Poilâne (7 November 1909 – 26 June 1993) was “the son of a lower-middle-class farming family in Normandy.” [21]Rushton, Susie, op. cit. [22]Geneanet. Pierre Léon Adrien POILÂNE. Accessed April 2020 at https://gw.geneanet.org/wikifrat?lang=en&n=poilane&oc=0&p=pierre+leon+adrien He was 23 at the time.

“My grandfather, Pierre Poilâne, opened the bakery in 1932, when he was just twenty-three, at 8 rue du Cherche-Midi in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés district of Paris. The son of farmers from Normandy, he had wanted to be an architect, but his parents couldn’t afford to send him to university. An interest in the mechanics of wood-fired ovens introduced him to baking, and he apprenticed in several boulangeries around France.” [23]Poilâne, op. cit., page 17.

Its location, at 8, Rue du Cherche-Midi in Saint-Germain-des-Prés neighbourhood in the Sixth Arrondissement, put it near other bakeries at the time:

“At the time, Poilâne Bakery was the smallest of the five bakeries on the street, though eighty-two years later it is the only one still in operation.” [24]Martins, Patrick, op. cit.

The building Poilâne set up in had originally been part of a convent, and did have in it an oven from the 1700s. [25]Rourke, Mary. Lionel Poilâne, 57; French Baker Renowned for Round Loaves. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times. 6 November 2002. He replaced that original oven with one built to his own requirements, and it is still in use today: “The building my grandfather chose for Poilâne had originally housed a convent before becoming a bakery at around the time of the French Revolution. He replaced the oven in the tunnel-like stone basement with one built to his own specifications.” [26]Poilâne, Apollonia, op. cit., page 17.

At the time, Saint-Germain-des-Prés was a bohemian neighbourhood. Pierre would sometimes accept art as payment: “Locals came in daily for a whole loaf or, if they couldn’t afford that, for a few slices that my grandfather sold by weight (something we still do). When an artist couldn’t pay, my grandfather arranged a trade: bread for art—provided the paintings or drawings featured Poilâne in some way.” [27]ibid.

Pierre and his wife Charlotte Grajeon (1905-1977) had three children, Max (born 1941), Madelaine, and Lionel (10 June 1945 – 31 October 2002) the youngest.

Pierre died on 26 June 1993 at the age of 83 in Longjumeau, Essonne, France. [28]Geneanet. Pierre Léon Adrien POILÂNE. Accessed April 2020 at https://gw.geneanet.org/wikifrat?lang=en&n=poilane&oc=0&p=pierre+leon+adrien

Lionel Poilâne

At the age of 14, Lionel left school and began working in his father’s bakery, as had Max before him. Lionel married Irena Borzena Ustjanowski, a Polish American designer, architect, and gallery owner. Professionally as an artist, she used her initials IBU. [29]Her gallery is online at http://www.ibugallery.fr/They had two girls, Apollonia, the elder, and Athéna, the younger. Apollonia was actually born in New York. [30]Agnew, Harriet. On the rise: taking a baking dynasty to the next level. London: Financial Times. 8 March 2018.

His father, Pierre, had a stroke in 1971. [31]Sancton, Tom, op. cit.

Lionel began to take over the company in 1973 at the age of 28.

He expanded, opening a second Paris bakery in 1974 [32]Sancton, Tom, op. cit., and then a third in Paris, and then one in London, England, at 46 Elizabeth Street, Belgravia, SW1 (opened June 2000), making it the site of London’s “first wood-burning oven since the Great Fire of 1666.” [33]Sancton, Tom, op. cit.

The only technological advance he introduced to the Poilâne technique was bringing in large electric mechanical mixers to do the dough kneading, but he left all the other work manual.

He also opened lunch places he called “Cuisines de Bar” (since renamed to “Comptoirs Poilâne”) and an established an international retail network supplied by bread out of the bakery in Bièvres.

He 1993, he was made a Knight of the “Ordre national du Mérite (National Order of Merit)” for services to the economy.

Lionel and his wife Irena were killed in a helicopter crash on 31st October, 2002. He was flying the helicopter, and attempting a landing at their holiday home on the Île des Rimains. “For reasons still unknown, the chopper crashed into the fog-enshrouded English Channel just 500 yards from the island. Investigators found Lionel’s body still strapped in his seat under 30 feet of water. Irena’s body was never found.” [34]Sancton, Tom, op. cit.

He was 57 when he died.

Île des rimains, where Lionel Poilane and his wife died in a helicopter accident at the end of October 2002. The island was bought in 2012 by a Pierre Kosciusko-Morizet, a French e-commerce pioneer. Falcon® Photography / flickr / 2017 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Front national rumours

In 1994, he received the “Prix Renaissance de l’économie” from the group “le cercle Renaissance”, a group with some ties to an alt-right conservative political party, the “National Front”, and was invited to join the association. When he learned of the group’s association, he quit the group. “At the time, Lionel Poilane knew nothing about the political leanings of this association,” wrote Caroline Fourest and Fiametta Venner, co-authors of the Guide to Front National sponsors, certain that the baker was ensnared.” [35]Forcari, Christophe. Les Poilâne dans le pétrin FN. Paris: Libération. 21 November 2002.

In 1998, he repudiated rumours in the press that he financed the party: “Mais il a démenti dans la presse, en 1998, des rumeurs sur une aide qu’il aurait apportée au financement du Front national.” [36] Durand, Jacky. Le pain Poilâne a perdu son mitron. Paris, France: Libération. 2 November 2002.

Shortly after his death, the official paper of the National Front, the National-Hebdo, published an article on him saying “Goodbye to one of ours.” One of the key “supportive gestures” that a National Front official pointed to was Poilâne having donated pastries one Christmas to a children’s group that turned out to have a remote association with the party.

His daughters categorically rejected any association: “Following a tribute paid to Poilâne two weeks ago in National Hebdo under the title “Farewell to one of ours” (Libération of November 8), his two daughters, Apollonia and Athena, wrote to the Lepéniste [Ed: associated with Jean-Marie Le Pen] newspaper to assure that their father “was never a supporter of the National Front, whose values and ideas he did not share”. [37]Forcari, Christophe, op. cit.

In practice, Poilâne appears to have the opposite of an ideal National Front supporter, having actively supported causes that would be anathema to the far right political party by donating sizable sums of money to both pro-choice as well as lesbian and gay groups. One group that Poilâne supported, making reference to the children’s Christmas pastries that the National Front cited as evidence that Poilâne support their party, said:

“If we are to count the [pastries] offered by the company Poilâne, we regret to inform [the National Front] that the meetings of the pro choice association – which they hate – have also benefited, free of charge, from Viennoiseries by Lionel Poilâne. Personally, Lionel felt close to the defense of individual freedoms, so much so that he had offered to finance the insert announcing in Libération [newspaper] the launch of the PaCS Observatory [Ed: a gay and lesbian group.] (30,000 F). He also participated financially in pro-choice campaigns.” [38] “Si l’on en est à compter les petits déjeuners offerts par la société Poilâne, nous avons le regret d’informer Présent que les réunions de l’association ProChoix — qu’il exècre — ont aussi bénéficié, gratuitement, des viennoiseries de Lionel Poilâne. À titre personnel, Lionel se sentait proche de la défense des libertés individuelles, à tel point qu’il nous avait proposé de financer l’encart annonçant dans Libération le lancement de l’Observatoire du PaCS (30 000 F). Il a aussi participé financièrement aux campagnes de Prochoix…” ProChoix newsletter November 2002. Accessed April 2020 at http://prochoix.org/frameset/news_2002/nov_2002.html.

Apollonia Poilâne

Apollonia Poilâne took over the reins of the company at the age of eighteen on 2 November 2002, two days after the death of her parents. “The next morning, Apollonia addressed the Poilâne staff with a self-possession that would become characteristic: she was now in control of the business, she informed them.” [39]Rushton, Susie, op. cit.

Apollonia had been in training to take over the company one day: “From the age of 16, she spent summer holidays learning the craft of the boulanger, finishing her nine-month apprenticeship just before her parents died.” [40]Whittle, Natalie. The Professionals: Apollonia Poilâne, baker. London: Financial Times. 26 November 2011.

Her first years of managing the company were done long-distance while she did a degree at Harvard in the United States, where she majored in economics. She was able to oversee things remotely with things on the ground in Paris being looked after by “five senior managers, all longtime company veterans.” [41]Sancton, Tom, op. cit. Of her time at Harvard, she remembers that she had a hard time finding decent bread in Boston.

In her office is a bread chandelier (“which must be remade each year lest it go mouldy and crumble”.) [42]Rushton, Susie, op. cit.

Her sister Athena did a redesign of the store’s bags in 2006. [43]Apollonia U. Poilâne. Harvard University: The Harvard Crimson. 13 December 2006.

As of 2018, her company “has a [euro]12m turnover and makes between eight and 10 tonnes of bread a day, including 5,000 sourdough loaves. As well as to the French market, Poilâne bread is shipped to more than 40 countries. The business has a network of 1,500 retailers in France and worldwide.” [44]Agnew, Harriet, op. cit.

Max Poilâne

Max Poilâne, 87, Rue Brancion, 75015 Paris. 2009. Jean-François Gornet / wikimedia / 2009 / CC BY 2.0

The Max Poilâne SAS company is run by another branch of the Poilâne family.

In the 1970s, Max Poilâne had a falling out with his brother Lionel, four years younger than him.

In 1976, Max opened his own Poilâne bakery in a corner building at 87, Rue Brancion in the Fifteenth Arrondissement. Max’s daughter, Mylène, says Max opened his own bakery with the blessing of his father, Pierre, the founder of Poilâne. [45]”Max s’installera avec l’aide de son père Pierre en 1976.” https://www.max-poilane.fr/il_etait_une_fois.php

For years the two brothers fought in court, with Lionel challenging Max’s use of the Poilâne name as brand infringement.

In 1992, a court ruled that Max was entitled to operate under his name provided he used the branding as “Max Poilâne” to distinguish it from the other Poilâne.

In 2008, a court slapped the hands of the “Max Poilâne” company and fined them 15,000 euros in damages and interest for not keeping the distinction clear enough. [46]”le prénom Max doit précéder Poilâne sur tous les documents de référence, emballage ou affiche commerciale «sur la même ligne, dans les mêmes caractères de même dimension, de même couleur et de même tonalité». Et c’est là que le bât blesse. À plusieurs reprises, la société d’Apollonia Poilâne a pu faire constater qu’à la fois sur des vêtements professionnels ou sur des emballages de produits le prénom Max était apposé en plus petits caractères que le nom Poilâne.” Dromard, Thiébault. Max Poilâne gagne la bataille du pain. Paris: Le Figaro. 21 April 2008.

At one point, Max reputedly let it be known publicly that he thought his brother Lionel was a National Front member, an assertion that would not have smoothed relations any with the other branch of the Poilâne family: “Le frère de Lionel Poilâne a assuré que ce dernier avait bel et bien été membre du Front.” [47]Forcari, Christophe, op. cit.

Max and his wife Sophie had three children: Mylène, Sophie and Julien. Mylène began working in the shop in 1983, and later took over the Rue Brancion bakery.

The Max Poilâne website as of 2020 lists one Max Poilâne bakery in Paris (run by Mylène) and three Max Poilâne bakeries in Lyon, run by her brother Julien (18, rue Casimir Périer; 17, av. de Saxe ; 76 av. des Frères Lumière ) [48]Accessed April 2020 at https://www.max-Poilâne.fr/

The Max Poilâne version of the famous miche Poilâne has a slightly less acidic taste — deliberately so, they say:

“We have a less acid taste to our bread. We feel that it’s easier to marry with food.” [49]Collins, Lauren, op. cit.

Though criticized by the other Poilane company for this different taste, it perhaps does not contradict one of Apollonia’s reputed bread proverbs, “Bread should not steal the quality of the meal.” [50]Collins, Lauren, op. cit.

Visually, the two miches can be distinguished by how the loaves have been docked. The slash on the Max Poilâne is a square around the outside of the top, instead of a P. This is how older photos and paintings of the bread from back in Pierre Poilâne’s day show it.

In addition to its signature miche, Max Poilâne sells a few other breads nearly identical to the bread lineup from the other Poilâne store. Rye bread (“pain de seigle”), walnut bread (“Pain aux noix”), rye and currant bread (“Le pavé aux raisins”)and a white sandwich loaf (“Pain de mie”), as well as a rye sandwich loaf (“pain de siegle moulé”)

Literature and Lore

“[Lionel Poilâne]’s round boule was his alternative to the baguette, the long narrow sticks of bread that he refused to carry in his shop. They are not authentic, he often pointed out; they were introduced to France by an Austrian ambassador in the mid-19th century.” [51]Rourke, Mary, op. cit.

Books by Poilâne

Apollonia was quoted in the New Yorker Magazine in 2012 as saying, “I don’t believe in making bread at home.” [52]Collins, Lauren, op. cit.

Her views appear to have evolved. In 2019, she published a book of advice on home bread baking for the American market entitled “Poilâne: The Secrets of the World-Famous Bread Bakery.” The book seeks to instruct people in the general techniques of making some breads similar to the quality produced by Poilâne. Anyone looking for it to be solely a bread recipe book may be disappointed, though, some reviewers have cautioned: it contains only about ten actual recipes for making bread. All the other recipes concern pastries, or are recipes that call for bread as an ingredient. That being said, the book title does say it is about “secrets”, and it does appear to deliver on that: it contains a great deal of advice on technique and heritage knowledge garnered over three generations of family baking, and lifts the curtain on the daily operations of the bakery.

Books by Lionel Poilâne

- 1981 : Guide de l’amateur de pain, Robert Laffont, Paris

- 1982 : Faire son pain, Dessain et Tolra, coll. « Manu presse / Carré bleu », Paris

- 1985 : Pain, cuisine et gourmandises, avec Ginette Mathiot, Albin Michel, Paris

- 1989 : Le Guide Poilâne des traditions vivantes et marchandes, Robert Laffont, Paris

- 1998 : Guide Poilâne des mille artisans : Des métiers du papier, du tissu, du bois, du métal, etc., Le Cherche midi, collection « Guides », Paris

- 1999 : Les Meilleures Tartines de Lionel Poilâne, photogr. Patrice Bondurand et Véronique Devoldère, Grancher, Paris

- 2005 : Le pain par Poilâne, with Apollonia Poilâne, Le Cherche midi, Paris (not primarily a recipe book, more a history and information book. Book sites do list Lionel as the author, even though he was deceased at the time of publication.)

Books by Apollonia Poilâne

- 2011 : Du pain et des mots (mostly a commentary about bread rather than a recipe or technique book)

- 2019 : Poilâne: The Secrets of the World-Famous Bread Bakery (about ten recipes for bread. Other recipes are for pastries, and for cooking with bread as an ingredient.)

Sources

Agnew, Harriet. On the rise: taking a baking dynasty to the next level. London: Financial Times. 8 March 2018.

Apollonia U. Poilâne. Harvard University: The Harvard Crimson. 13 December 2006.

Arnaud, Jean-François Arnaud. Comment la fille aînée du boulanger Poîlane dirige l’entreprise familiale. Paris: Challenges Magazine. 26 April 2017.

Chelminski, Rudolph. Any Way You Slice it, a Poilâne Loaf is Real French Bread. Smithsonian Magazine. January 1995.

Collins, Lauren. A daughter upholds the traditions of France’s premier baking dynasty. New York: The New Yorker. 26 November 2012.

Désavie, Patrick. La célèbre et rebondie miche Poilâne. Antony, Hauts-de-Seine, France: L’Usine Nouvelle. 11 August 2017.

Dromard, Thiébault. Max Poilâne gagne la bataille du pain. Paris: Le Figaro. 21 April 2008.

Lebovitz, David. Poilâne. Blog posting 1 December 2011. Accessed April 2020 at https://www.davidlebovitz.com/Poilâne-bakery-cuisine-de-bar-paris/

Rourke, Mary. Lionel Poilâne, 57; French Baker Renowned for Round Loaves. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times. 6 November 2002.

Plummer, Todd. Paris’s Most Famous Bakery Spills the Secret to a Perfect Loaf. New York: Vogue Magazine. 28 September 2019.

Rushton, Susie. Apollonia Poilâne. In: The Gentlewoman Magazine. London, England: Fantastic Woman Ltd. Issue n° 4, Autumn & Winter 2011 .

Sancton, Tom. Apollonia Poilâne inherits a famous Paris bakery. New York: Fortune Magazine. 19 January 2007.

Whittle, Natalie. The Professionals: Apollonia Poilâne, baker. London: Financial Times. 26 November 2011.

References

| ↑1 | Poilâne, Apollonia. The Secrets of the World-Famous Bread Bakery. New York: Houghton Mifflin. 2019. Page 18. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Collins, Lauren. A daughter upholds the traditions of France’s premier baking dynasty. New York: The New Yorker. 26 November 2012. |

| ↑3 | Plummer, Todd. Paris’s Most Famous Bakery Spills the Secret to a Perfect Loaf. New York: Vogue Magazine. 28 September 2019. |

| ↑4 | Rushton, Susie. Apollonia Poilâne. In: The Gentlewoman Magazine. London, England: Fantastic Woman Ltd. Issue n° 4, Autumn & Winter 2011. |

| ↑5 | Lebovitz, David. Poilâne. Blog posting 1 December 2011. Accessed April 2020 at https://www.davidlebovitz.com/Poilâne-bakery-cuisine-de-bar-paris/ |

| ↑6 | Rushton, Susie, op. cit. |

| ↑7 | Poilâne, Apollonia, op. cit., page 37. |

| ↑8 | ”the seventy-loaf capacity of the bakery’s single oven…” ibid., page 18. |

| ↑9 | Rushton, Susie, op. cit. |

| ↑10 | Poilâne, Apollonia, op. cit., page 18. |

| ↑11 | ibid. |

| ↑12 | Oxford says the term ‘manufactory’ has been around in English since at least 1630, though it is now obsolete: “Servile and manufactory men that should serve the uses of the world in the handicrafts” (Henry Lord, Banians and Persees, 70, 1630). “A sort of idol who did … daily create men by a sort of manufactory operation” (Jonathan Swift, A Tale of a Tub, 1704).” The term in modern times has now been used as well by other bread bakeries, such as the Tartine Bakery in San Francisco (founded 2002.) |

| ↑13 | Sancton, Tom. Apollonia Poilâne inherits a famous Paris bakery. New York: Fortune Magazine. 19 January 2007. |

| ↑14 | Collins, Lauren, op. cit. |

| ↑15 | Collins, Lauren, op. cit. |

| ↑16 | Martins, Patrick. The Carnivore’s Manifesto: Eating Well, Eating Responsibly, and Eating Meat. Boston, MA: Little, Brown. 2014. |

| ↑17 | Collins, Lauren, op. cit. |

| ↑18 | Rushton, Susie, op. cit. |

| ↑19 | Sancton, Tom, op. cit. |

| ↑20 | Collins, Lauren, op. cit. |

| ↑21 | Rushton, Susie, op. cit. |

| ↑22 | Geneanet. Pierre Léon Adrien POILÂNE. Accessed April 2020 at https://gw.geneanet.org/wikifrat?lang=en&n=poilane&oc=0&p=pierre+leon+adrien |

| ↑23 | Poilâne, op. cit., page 17. |

| ↑24 | Martins, Patrick, op. cit. |

| ↑25 | Rourke, Mary. Lionel Poilâne, 57; French Baker Renowned for Round Loaves. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times. 6 November 2002. |

| ↑26 | Poilâne, Apollonia, op. cit., page 17. |

| ↑27 | ibid. |

| ↑28 | Geneanet. Pierre Léon Adrien POILÂNE. Accessed April 2020 at https://gw.geneanet.org/wikifrat?lang=en&n=poilane&oc=0&p=pierre+leon+adrien |

| ↑29 | Her gallery is online at http://www.ibugallery.fr/ |

| ↑30 | Agnew, Harriet. On the rise: taking a baking dynasty to the next level. London: Financial Times. 8 March 2018. |

| ↑31 | Sancton, Tom, op. cit. |

| ↑32 | Sancton, Tom, op. cit. |

| ↑33 | Sancton, Tom, op. cit. |

| ↑34 | Sancton, Tom, op. cit. |

| ↑35 | Forcari, Christophe. Les Poilâne dans le pétrin FN. Paris: Libération. 21 November 2002. |

| ↑36 | Durand, Jacky. Le pain Poilâne a perdu son mitron. Paris, France: Libération. 2 November 2002. |

| ↑37 | Forcari, Christophe, op. cit. |

| ↑38 | “Si l’on en est à compter les petits déjeuners offerts par la société Poilâne, nous avons le regret d’informer Présent que les réunions de l’association ProChoix — qu’il exècre — ont aussi bénéficié, gratuitement, des viennoiseries de Lionel Poilâne. À titre personnel, Lionel se sentait proche de la défense des libertés individuelles, à tel point qu’il nous avait proposé de financer l’encart annonçant dans Libération le lancement de l’Observatoire du PaCS (30 000 F). Il a aussi participé financièrement aux campagnes de Prochoix…” ProChoix newsletter November 2002. Accessed April 2020 at http://prochoix.org/frameset/news_2002/nov_2002.html. |

| ↑39 | Rushton, Susie, op. cit. |

| ↑40 | Whittle, Natalie. The Professionals: Apollonia Poilâne, baker. London: Financial Times. 26 November 2011. |

| ↑41 | Sancton, Tom, op. cit. |

| ↑42 | Rushton, Susie, op. cit. |

| ↑43 | Apollonia U. Poilâne. Harvard University: The Harvard Crimson. 13 December 2006. |

| ↑44 | Agnew, Harriet, op. cit. |

| ↑45 | ”Max s’installera avec l’aide de son père Pierre en 1976.” https://www.max-poilane.fr/il_etait_une_fois.php |

| ↑46 | ”le prénom Max doit précéder Poilâne sur tous les documents de référence, emballage ou affiche commerciale «sur la même ligne, dans les mêmes caractères de même dimension, de même couleur et de même tonalité». Et c’est là que le bât blesse. À plusieurs reprises, la société d’Apollonia Poilâne a pu faire constater qu’à la fois sur des vêtements professionnels ou sur des emballages de produits le prénom Max était apposé en plus petits caractères que le nom Poilâne.” Dromard, Thiébault. Max Poilâne gagne la bataille du pain. Paris: Le Figaro. 21 April 2008. |

| ↑47 | Forcari, Christophe, op. cit. |

| ↑48 | Accessed April 2020 at https://www.max-Poilâne.fr/ |

| ↑49 | Collins, Lauren, op. cit. |

| ↑50 | Collins, Lauren, op. cit. |

| ↑51 | Rourke, Mary, op. cit. |

| ↑52 | Collins, Lauren, op. cit. |