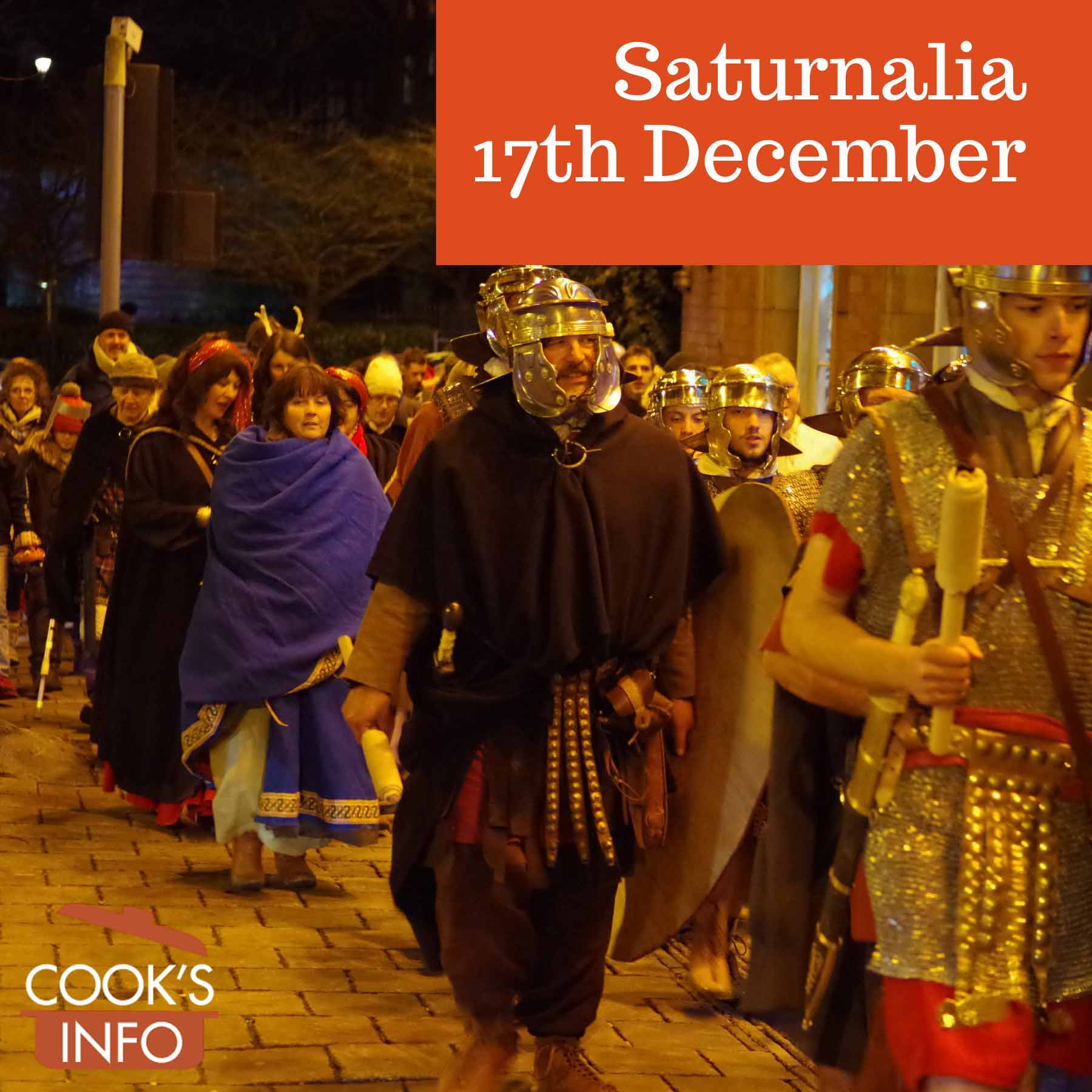

Saturnalia parade in Chester, England, December 2013. Donald Judge / flickr.com / 2013 / CC BY 2.0

Saturnalia is the 17th of December.

Saturnalia in Rome was a week-long winter celebration at the time of year when the Winter Solstice occurred. It was celebrated for over 500 years.

#Saturnalia

See also: Christmas Day, Roman Holidays, Roman Food

Saturnalia Traditions

It was a time of fun and freedom.

People donned red, soft woolen caps (which remind one of Santa Hats, or of the hats we now pull out of Christmas crackers), and decorated their houses with boughs of greenery. Courts, schools and many businesses closed for the holidays.

People spent their time gambling and feasting. Public banquets seem to have started by 217 BC. Lords of Misrule (Saturnalicius princeps) were appointed for the festivities and feasts. In wealthy houses, it was a time of role reversal, when masters would wait on their slaves.

Saturnalia by Antoine-François Callet / wikimedia / 1783 / CC0 1.0

By tradition, it became as well a period during which you could say what you wanted without fear of punishment. The Roman poet Horace says to his slave:

“Come now, speak up!

Take advantage of the freedoms December allows,

As our ancestors intended.” — Horace, Satires 2.7.4-5

Unsurprisingly, it also became a time for expressing political satire at plays.

In our modern Gregorian calendar, the start of the Roman holiday of Saturnalia now falls on 17th December.

It was originally celebrated just one day, to honour Saturn. With the feast for his wife Ops, though, falling two days later on 19 December, the two soon blended to become three days, and before you knew it, it was a whole week. (The exact dates shifted about a bit until Julius Caesar fixed the calendar, creating the “Julian” calendar.)

Augustus made attempts to reduce the holiday period back to three days; Caligula tried to reduce it back to five days, but even that didn’t really work.

It addition to the fun and freedom, it was also a time of gift-giving.

People would give each other candles (cerei) as gifts, likely as cheering then as they are now at the darkest time of year. Sprigs of holly were also given. Small dolls made of porcelain or clay were given to children. Gifts were sent by customers and clients to their patrons at Saturnalia. The gifts could be perishable goods, such as food and drink, or non-perishable goods.

By the middle of the 300s, the Christians had appropriated many of the customs. Or, the customs appropriated Christianity, it could also be argued. The traditions first became part of Twelfth Night, and later, shifted to Christmas.

Saturnalia parade in Chester, England, December 2013. Donald Judge / flickr.com / 2013 / CC BY 2.0

Literature and Lore

The Roman poet Martial lists some of the gifts a Roman lawyer named ‘Sabellus’ received at Saturnalia from his clients:

“The Saturnalia have made Sabellus a rich man. Justly does Sabellus swell with pride, and think and say that there is no one among the lawyers better off than himself. All these airs, and all this exultation, are excited in Sabellus by half a peck of meal, and as much of parched beans; by three half pounds of frankincense, and as many of pepper; by a sausage from Lucania, and a sow’s paunch from Falerii; by a Syrian flagon of dark mulled wine, and some figs candied in a Libyan jar, accompanied with onions, and shell-fish, and cheese. From a Picenian client, too, came a little chest that would scarcely hold a few olives, and a nest of seven cups from Saguntum, polished with the potter’s rude graver, the day workmanship of a Spanish wheel, and a napkin variegated with the laticlave. More profitable Saturnalia Sabellus has not had these ten years.” (Epigrams, Book 4, Epigram XLVI. ) [1]Martial, Epigrams. Book 4. Bohn’s Classical Library (1897). Accessed January 2020 at http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/martial_epigrams_book04.htm

In his poems, Martial divided the types of Saturnalia gifts in two. He listed perishable goods in one set of epigrams he called “Xenia”, and non-perishable goods in his “Apophoreta”. Xenia were “guest gifts” and apophoreta means “things to be taken away”.

The “dark mulled wine” mentioned in English is actually the type of processed wine known as defritum in the original.

For reference, here is the same passage as above, but in Martial’s native Latin:

“Saturnalia divitem Sabellum

fecerunt: merito tumet Sabellus,

nec quemquam putat esse praedicatque

inter causidicos beatiorem.

Hos fastus animosque dat Sabello

farris semodius fabaeque fresae,

et turis piperisque tres selibrae,

et Lucanica ventre cum Falisco,

et nigri Syra defruti lagona,

et ficus Libyca gelata testa

cum bulbis cocleisque caseoque.

Piceno quoque venit a cliente

parcae cistula non capax olivae,

et crasso figuli polita caelo

septenaria synthesis Sagunti,

Hispanae luteum rotae toreuma,

et lato variata mappa clavo.

Saturnalia fructuosiora

annis non habuit decem Sabellus.” [2]Paley, F.A. and Stone, W.H. M. Val. Martialis Epigrammata selecta. London: Whittaker. 1885. Page 120 – 121.

History Notes

Ruins of the Temple of Saturn (eight columns to the far right) in Roman Forum. Carla Tavares / wikimedia / 2015 / CC BY-SA 3.0

Saturn was not only the god of sowing fields, he was also the Lord of Mirth and Joviality. The foundations of Saturn’s temple are still in Rome, in the Roman forum (the first forum in Rome.)

The temple was a massive one. It also housed the state treasury and at one one, the state archives.

In the temple was a statue of Saturn, made of ivory. At some point, it may have been made of wood. It was hollow, and filled with olive-oil:

“The Elder Pliny reports that the ivory statue of Saturn at Rome was preserved by having its interior filled with oil. ‘There is also a use of old olive-oil for certain kinds of diseases, and it is also deemed to be serviceable for preserving ivory from decay: at all events, the inside of the statue of Saturn at Rome has been filled with oil.’ [3]Lapatin, Kenneth D.S..Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World Page. New York: Oxford University Press. 2001. 125.

The statue’s feet were crossed, and “shackled” either by bands of wool or wood. “The bound feet, reported by Macrobius, served to restrain the power of the god.” [4]Ibid.

On the day of Saturnalia proper itself, 17th December, the bonds were removed to unleash the power of the god on his day.

“Now Saturn, slip your shackles and reign

With drunken December, insolent Wit

And the smiling god of Mockery.

Let Jupiter wrap the world in cloud

And threaten to flood the fields

With winter rain, so long as Saturn

Showers us with abundant gifts.

Today one table feasts us all

In common, mixing young and old,

Men and women, high and low:

Here Liberty puts Rank in its place.” — Statius, Occasional Poems 1.6.1-7; 25-7; 43-45

On this day, the statue of Saturn was carried in procession to the forum for a feast. Some historians feel a lighter copy of the statue would have been used for the procession.

Historian Agnes Michels notes that though Saturnalia was technically a single day, as is our Christmas, the festival season actually extended several days. She also notes that Saturnalia was a rare Roman festival which went into the night:

“Strictly speaking, the festival lasts only one day, on which the sacrifice is made, but the holiday spirit which it evokes lasts for several days, obscuring some less popular ceremonies which follow it. It is like our Christmas “holidays,” which last until New Year’s Day, although the only legal or religious holiday is Christmas itself. There seems to be something about the dead of winter just before the days begin to lengthen noticeably that makes people need to relax and enjoy themselves. The Saturnalia does not mark the winter solstice, which came then on December 25, although the republican calendar was so inaccurate that early Romans would never have been able to predict it precisely.

A strange feature of this cult is that its rites are performed Graeco ritu capite aperto, “in Greek rite with uncovered head,” so that the sacrificer does not pull his toga up over his head as he does in Roman rite. No satisfactory explanation of this peculiarity has been discovered. Could the ritual have been developed before the Romans started to wear togas? The extended revelry characteristic of the Saturnalia seems to have been introduced in 217 BC, when Hannibal was winning one battle after another. As happens when people are frightened, an extraordinary number of prodigies was reported which had to be expiated by extraordinary offerings to the gods (Livy 22.1.8-10). When December came there was a normal sacrifice at the temple of Saturn, and a lectisternium, and then an innovation. A convivium publicum, a feast, was provided out of public funds for all citizens — per urbem Saturnalia diem et noctem clamata — and the people were ordered to preserve this celebration forever. Romans do not approve of night time celebrations as a rule, but this must have been a wonderful chance for people suffering great apprehension to let off steam. It sounds rather like New Year’s Eve in Times Square.

From this presumably originated the peacetime Saturnalia, of which the best known feature was the (temporary) freedom of slaves, who sat at banquets with their masters and enjoyed relaxed discipline. The celebrations gradually expanded to last for several days, sometimes three, sometimes even seven, and the custom survived for centuries. This was also the time for giving traditional gifts, wax candles and sigilla, objects made of pottery.” [5]Michels, Agnes K. “Roman Festivals: October—December.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 68, no. 1, American Classical League, 1990, pp. 11, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43919166.

References

| ↑1 | Martial, Epigrams. Book 4. Bohn’s Classical Library (1897). Accessed January 2020 at http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/martial_epigrams_book04.htm |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Paley, F.A. and Stone, W.H. M. Val. Martialis Epigrammata selecta. London: Whittaker. 1885. Page 120 – 121. |

| ↑3 | Lapatin, Kenneth D.S..Chryselephantine Statuary in the Ancient Mediterranean World Page. New York: Oxford University Press. 2001. 125. |

| ↑4 | Ibid. |

| ↑5 | Michels, Agnes K. “Roman Festivals: October—December.” The Classical Outlook, vol. 68, no. 1, American Classical League, 1990, pp. 11, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43919166. |