Gerhard Gellinger / Pixabay.com / 2018 / CC0 1.0

Mother’s Day in the UK has been celebrated on the fourth Sunday in Lent since at least the 1500s. Only little by little, however, did it evolve to actually be about mothers.

History of Mothering Sunday

Traditionally Mothering Sunday was the day that people went “mothering”. [1]The Oxford English Dictionary notes that this term appeared as early as 1644.

“Mothering” was visiting your home church — the one you were baptized in or had attended when you were young, which is to say, your “mother church”. This gave people who had moved away from their home parish a chance to reunite with their old friends and their family. Association with honoring your actual earthly mother naturally developed over time, so people would often bring presents for their mother.

Servants would often even be given the day off. It became a bit of a minor festive break in Lent. The day was also called “midlenting”. [2]1720 C. Wheatley Illustr. Bk. Common Prayer (ed. 3) 225 “The Appointment of these Scriptures upon this Day [sc. Midlent-Sunday], might probably give the first Rise to a Custom still retain’d in many Parts of England, and well known by the name of Midlenting or Mothering.” OED Third Edition 2002.

The tradition was largely fading by the start of the 1900s. Inspired by the American Mother’s Day, a woman named Constance Penswick [Adelaide] Smith (1878–1938) wanted to revive Mothering Sunday in England. To that end, she wrote two plays (In Praise of Mother: A story of Mothering Sunday (1913) and A Short History of Mothering Sunday (1915)), as well as a booklet “The Revival of Mothering Sunday (1921). She also founded the “Society for the Observance of Mothering Sunday”. [3]Smith, Constance Adelaide. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093%2Fref%3Aodnb%2F103415 . . Her efforts eventually paid off and the day was revived, though with a more American-style emphasis on mothers rather than on the Church.

Today is also known as Lætare Sunday in the Church calendar.

#MotheringSunday

Food for Mothering Sunday

Simnel cake is traditional on this day. It was made by servant girls to give as a present to their mothers when they went home to visit on this day. Simnel cake is also — or rather, mostly — made at Easter now.

In Yorkshire, carlings were made on this day as well, instead of on the following Sunday (the fifth Sunday in Lent) as was the practice elsewhere in England, particularly in the north.

In her 1883 book “Shropshire Folklore” Charlotte Sophia Bume (1850-1923) recounts the practice of Mothering Sunday, and its association with veal, and simnel cakes:

“Half-way through Lent the fast is interrupted by the kindly home-festival of ‘Mothering Sunday.’ Whether this was suggested by the occurrence of the history of the Feeding of the Five Thousand, and the mention of ‘Jerusalem which is above, which is the mother of us all’, in the Church services for the day, or whether the Epistle and Gospel were chosen to suit the customs of the season, who shall say? But in very recent days, old-fashioned families might still be met with here and there, who observed the ‘pious’ custom of visiting their mother on Mothering Sunday. I could name one old lady in South Staffordshire, whose four sons yearly dined with her on that day up to within the last fifteen years, one of them making a railway journey of some length in order to do so: and I am told of a large family at Aston Boterel, under the Brown Clee hill, who kept up the same custom even more recently. Around Ludlow it appears to be generally observed in the humbler ranks of life. The Shrewsbury Journal of March 26th, 1879, says that ‘Sunday last being Mid-lent or what is generally called in some parts of Shropshire ‘Mothering Sunday’ a considerable number of lads and lasses observed the feast in Ludlow and its neighbourhood. A good sprinkling of young people came into the town, notwithstanding the biting north-east wind which was blowing during the whole day.’ It is further added, that the butchers’ shops at the end of the preceding week were stocked with an unusually large supply of veal, in preparation for ‘the veal and rice pudding the family dish always placed before the young folk according to tradition on Mothering Sunday’.

Whether from a reminiscence of the fatted calf killed to welcome the returning prodigal, or simply from the fact that veal is the meat specially in season at the time of year, a roasted loin of veal is the favourite piéce de résistance for the Mothering Sunday dinner of ‘bettermost’ families wherever the festival is observed and at Pulverbatch it was customarily supplemented by a dish of custard and ‘the last of the mincemeat’ which some people carefully keep till Easter Day. At Stottesden in South Shropshire, in the early years of the present century, the Mothering Sunday supper consisted of ‘fraises’ — thick pancakes, more solid than those of Shrove Tuesday, eaten with sweet sauce.

The very name of Mothering Sunday seems to have vanished from the popular mind in North Shropshire. In the South it is still retained, in places where the custom which gave rise to it is no longer generally observed. The famous ‘Shrewsbury Simnels’ have no doubt helped to keep it alive. These cakes are still made and displayed for sale by the confectioners of Shrewsbury every year in preparation for the family feast of Midlent and are eaten by many who do not heed the pious habit of mothering which they were intended to celebrate.” [4]Bume, Charlotte Sophia. Shropshire Folk-lore: A Sheaf of Gleanings. London: Trubner & Co. 1883. Pp. 323-324.

George David Rosenthal (1881 – 1938), an Anglican priest, wrote:

“This annual return visit, signalized as tradition demanded it should be by gifts on both sides, must have acted as a powerful influence to strengthen and renew the bonds of family love. The young folk took as a present for their parents a small cake known as a Simnel. The parents provided “furmity” or “frumenty,” a dish of hulled wheat boiled in milk, and seasoned with cinnamon and sugar. In the North of England and in Scotland, however, the plat du jour was steeped pease, fried in butter, with pepper and salt. These pancakes were called Carlings, and Carling Sunday became the local name for the day.

Tid, Mid, and Misera,

Carling, Palm, and Paste-egg Day,remains in the North of England as an enumeration of Sundays in Lent and of Easter Day, the first three terms being probably taken from names in the ancient service-books for the respective days.

In shape the Simnel cake resembled a pork pie, but in materials it was a rich plum pudding inside a stiff and hard pastry crust. Simnels were made up very stiff, tied up in a cloth and boiled for several hours, after which they were brushed over with egg and then baked. When ready for the table, the crust was as hard as if made of wood. This circumstance has given rise to various stories of the manner in which they have at times been treated by persons to whom they were sent as a present, and who had never seen them before: one ordering the Simnel to be boiled to soften it, and another taking hers for a footstool! In old times they were often stamped with the figure of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

The word Simnel, I regret to say, is derived from the Latin Similia, meaning wheat-flour. My regret is due to the fact that the legendary derivations are much quainter and more delightful. Some assert that the father of Lambert Simnel, the pretender to the throne of Henry VII., was a baker, and in consequence of the celebrity he gained by the acts of his son, his cakes have retained his name. Here is an even more curious legend which has been handed on from time immemorial in Shropshire villages. I give it as far as possible in the words of a very old Salop lady, who was told it when a little girl by her grandmother.

Long ago, there lived an honest old Shropshire couple. I do not know their surnames, but their Christian names were Simon and Nelly. It was the custom at Easter to gather their children about them and thus for the whole family to meet together once a year at the old homestead. The fasting time of Lent was just ending, but they still had left some of the unleavened dough which had been prepared on Shrove Tuesday to make bread during the forty fasting days. Nelly was a very frugal housewife, and it grieved her to waste anything. So she suggested to her husband that they should use the remains of the Lenten dough to make a cake to regale the assembled family. Simon readily agreed to the proposal, but, quoth he: “Lenten dough is ill-fare for feasting. Were it not well to put within it what is left of the Christmas plum-pudding? This methinks will be a gay surprise to the young folk when they have made their way through the less tasty crust.” So far all went forward harmoniously; but when the cake was made, a subject of violent discord arose. Simon insisted that being pudding, it should be boiled, while Nelly no less passionately contended that being dough, it should be baked. The dispute, sad to tell, passed from words to blows, for Nelly, not choosing to let her province in the household be thus interfered with, jumped up and threw her baking-stool at Simon; while he, for his part, seized a besom and applied it with right good will to the head and shoulders of his spouse. The battle waxed so warm that it might have had a serious result, had not Nelly, who was beginning to get the worst of the encounter, suggested a way out of the difficulty. “If we go on like this,” says she, “the children will be here to find us quarrelling, and no cake for them. Let us boil it first, and then bake it, and all will be well.” Simon agreed to this, the big pot was set on the fire, the pieces of besom used for firing, and the broken pieces of the stool thrown on to boil the pot, so that no traces of the encounter should be left. Some eggs which had been broken in the scuffle were used to coat the outside of the pudding when boiled, which gave it the shining gloss it possesses as a cake. This new and admirable production so delighted the young folk, that thereafter each year they brought one home as a present to their parents. It became known as the cake of Simon and Nelly, but as time went on, only the first part of each name was preserved and joined together, so that ever since the cake has been known as Simnel.” — George David Rosenthal (1881 – 1938). In: The Holy Angels. Anglo Catholic Pamphlets. Collection of pamphlets issued by The Church Literature Association, The Catholic Literature Association and the Society of SS. Peter and Paul. 1900.

Literature and Lore

In 1814, a writer in Berkshire, England, pronounced Mothering Sunday to have long-since died out in southern England, but provided some memories of the food involved on the day:

“March 20. Midlent Sunday. This day received the appellative of Midlent Sunday, because it is the fourth, or middle Sunday, between Quadragesima, or the first Sunday in Lent, and Easter Sunday, by which latter, the Lenten Season is governed: several of our ecclesiastical writers denominate it Dominica Refectionis, or the Sunday of Refreshment, a term considered as having been applied to it, from the Gospel of the day treating of our Saviour’s miraculous feeding of the five thousand, and from the first lesson in the morning, containing the relation of Joseph entertaining his brethren: while the common or vulgar appellation which this day still retains is Mothering Sunday, a term expressive of the ancient usage of visiting the Mother (Cathedral) Churches of the several dioceses, when voluntary offerings (then denominated Denarii Quadrageminales, now the Lent or Easter offerings) were made, which by degrees were settled into an annual composition, or pecuniary payment charged on the parochial priests, who were presumed to have received these oblations from their respective congregations. The public processions have been discontinued ever since the middle of the 16th century, and the contributions, made upon that occasion, settled into the present trifle paid by the people under the title of Easter Offerings: but the name of Mothering Sunday is still not unaptly applied to this day; and a custom which was substituted by the commonality, is yet practised in many places, particularly in Cheshire, of visiting their natural mother, instead of the Mother Church, and presenting to her small tokens of their filial affection, either in money or trinkets, or more generally in some species of regale, such as frumety, fermety or frumenty, so called from Frumentum (wheat being its principal ingredient), which being boiled in the whole grain, and mixed with sugar, milk, spice, and sometimes with the addition of raisins or currants, forms altogether an agreeable repast. This mark of filial respect has long since been abolished in the South, though another custom to which it gave way, of the landlords of public houses presenting messes of this nature to the families who regularly dealt with them, is within the memory of many persons yet living.” — The Calendarium. Windsor, Berkshire: The Windsor and Eton Express. Sunday, 13 March 1814. Page 3, col. 5.

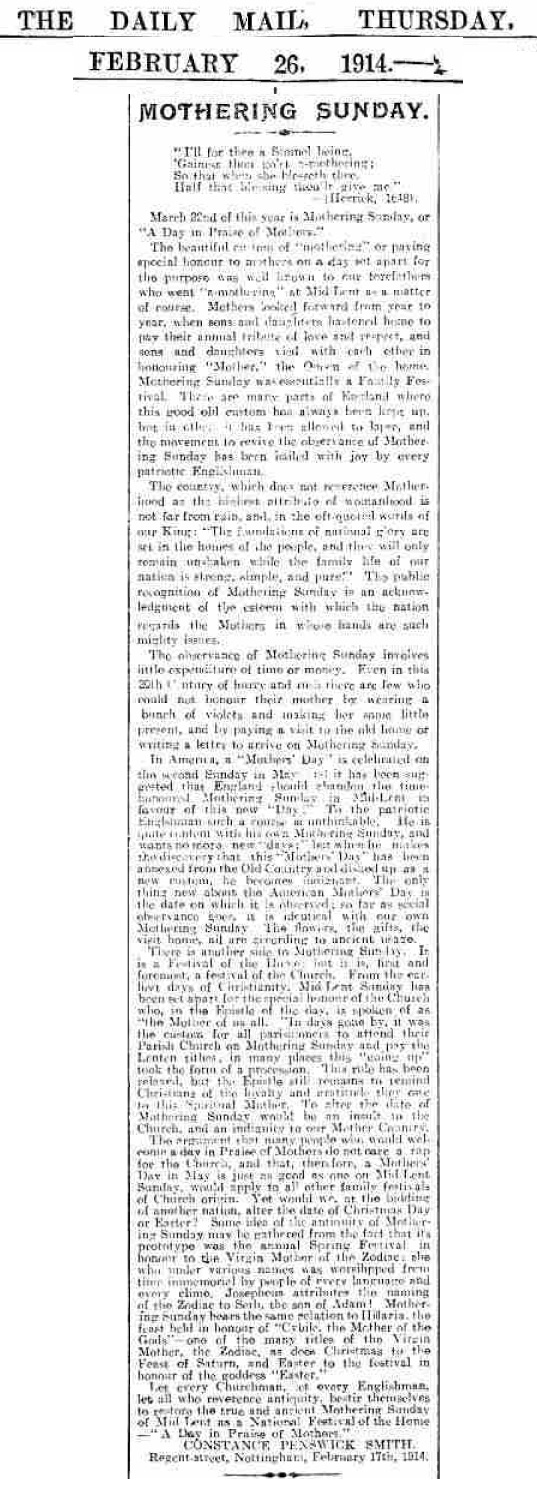

The efforts of Constance Penswick Smith (1878–1938) were ultimately successful in reviving Mothering Sunday by drawing on the example of American Mother’s Day for reinforcement, but, she had to fight a rearguard action against those who also wanted to simply move the date to harmonize with the Americans. To do this, in the following newspaper opinion column below written by her in 1914, she wraps herself in the flag, and portrays herself as a defender of Mother Church, even if she does call on ancient pagan gods as well while doing so:

MOTHERING SUNDAY.

“I’ll to thee a Simnell bring,

‘Gainst thou go’st a-mothering;

So that when she blesses thee,

Half that blessing thou’lt give me.”

(Robert Herrick, “A Ceremonie in Gloucester”, 1648).March 22nd of this year is Mothering Sunday, or ‘Day in Praise of Mothers.’ The beautiful custom of ‘mothering’ or paying special honour to mothers on a day set apart for the purpose was well known to our forefathers who went ‘a-mothering’ at Mid-Lent as a matter of course. Mothers looked forward from year to year, when sons and daughters hastened home to pay their annual tribute of love and respect, and sons and daughters vied with other in honouring ‘Mother’, the Queen of the home. Mothering Sunday was essentially a Family Festival. There are many parts of England where this good old custom has always been kept up, but in others it has been allowed to lapse, and the movement to revive the observance of Mothering Sunday has been hailed with joy by every patriotic Englishman.

The country which does not reverence Motherhood as the highest attribute of womanhood is not far from ruin, and, in the oft-quoted words of our King: ‘The foundations of national glory are set in the homes of the people, and they will only remain un-shaken while the family life of our nation is strong, simple, and pure.’ The public recognition of Mothering Sunday is an acknowledgment of the esteem with which the nation regards the Mothers in whose hands are such mighty issues.

The observance of Mothering Sunday involves little expenditure of time or money. Even in this 20th Century of hurry and rush there are few who could not honour their mother by wearing a bunch of violets and making her some little present, and by paying a visit to the old home or writing a letter to arrive on Mothering Sunday.

In America, a ‘Mothers’ Day’ is celebrated on the second Sunday in May, and it has been suggested that England should abandon the time-honoured Mothering Sunday Mid-Lent in favour of this new ‘Day’! To the patriotic Englishman such a course is unthinkable. He is quite content with his own Mothering Sunday, and wants no more new ‘days’; but when he makes discovery that this ‘Mothers’ Day’ has been annexed from the Old Country and dished up as a new custom, he becomes indignant. The only thing new about the American Mothers’ Day is the date on which it is observed; so far as social observance goes, it is identical with our own Mothering Sunday. The flowers, the gifts, the visit home, all are according to ancient usage.

There is another side to Mothering Sunday. It is a Festival of the Home: but it is, first and foremost, a festival of the Church. From the earliest days of Christianity, Mid-Lent Sunday has been set apart for the special honour of the Church who, in the Epistle of the day, is spoken of as ‘the Mother of us all.’ In days gone by, it was the custom for all parishioners to attend their Parish Church on Mothering Sunday and pay the Lenten tithes. In many places this ‘going up’ took the form of a procession. This rule has relaxed, but the Epistle still reminds Christians of the loyalty and gratitude they owe to this Spiritual Mother. To alter the date of Mothering Sunday would be an insult to the Church, and an indignity to our Mother Country.

The argument that many people who would welcome a day in Praise of Mothers do not care a rap for the Church, and that, therefore, a Mothers’ Day in May is just good as one on Mid-Lent Sunday, would apply to all other family festivals of Church origin. Yet would we, at the bidding of another nation, alter the date of Christmas Day or Easter? Some idea of the antiquity of Mothering Sunday may be gathered from the fact that its prototype was the annual Spring Festival in honour to the Virgin Mother of the Zodiac: she who under various names was worshipped from time immemorial by people of every language and every clime. Josepheus attributes naming of the Zodiac to Seth, the son of Adam! Mothering Sunday bears the same relation to Hilaria, the feast held in honour of ‘Cybile, the Mother of the Gods’ — one of many titles of the Virgin Mother, the Zodiac, as does Christmas to the Feast of Saturn, and Easter to the festival in honour of the goddess ‘Easter.’

Let every Churchman, let every Englishman, all who reverence antiquity, bestir themselves to restore the true and ancient Mothering Sunday of Mid-Lent as a National Festival of the Home — “A Day in Praise of Mothers.” CONSTANCE PENSWICK SMITH. Regent-street, Nottingham, February 17th, 1914.” — As printed in: Hull, Yorkshire, England: The Daily Mail, Hull Packet and East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Courier. Thursday, 26 February 1914. Page 4, col. 6.

Constance Peswick Smith. Mothering Sunday. Hull, Yorkshire, England: The Daily Mail, Hull Packet and East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Courier. Thursday, 26 February 1914. Page 4, col. 6.

References

| ↑1 | The Oxford English Dictionary notes that this term appeared as early as 1644. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 1720 C. Wheatley Illustr. Bk. Common Prayer (ed. 3) 225 “The Appointment of these Scriptures upon this Day [sc. Midlent-Sunday], might probably give the first Rise to a Custom still retain’d in many Parts of England, and well known by the name of Midlenting or Mothering.” OED Third Edition 2002. |

| ↑3 | Smith, Constance Adelaide. In: Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093%2Fref%3Aodnb%2F103415 . |

| ↑4 | Bume, Charlotte Sophia. Shropshire Folk-lore: A Sheaf of Gleanings. London: Trubner & Co. 1883. Pp. 323-324. |