Rovin / Pixabay.com / 2013 / CC0 1.0

Lent is the name of a period of fasting that takes place in the months leading up to Easter. The start date for Lent changes every year.

As early as the 300s AD, a handful of people in the Church (such as St Athanasius) were asking people to observe a fast for the forty days before Easter, but there was no real agreement on when a fast should be held, for how long, how strict, or even when was Easter, that the whole fast was leading up to.

Into the 400s, as the fasting fans brought more people around to the idea of a long fast, different people abstained from different things.

Most church people seemed to be plumping for a forty day fast, but there were some pockets of support for a period as long as fifty and sixty days before Easter.

In the 700s, Ash Wednesday was decided upon as the official start to Lent, and that it would be 40 days.

40 days represented the time that Moses and Christ spent in the wilderness (Moses on Mount Sinai); as well, Jesus was supposed to have lain 40 hours in the tomb, and the children of Israel spent 40 years in the desert.

By the early Middle Ages it was 40 weekdays and six Sundays (Saturday being a weekday back then.) You were allowed one meal a day in the evening. Over the centuries, some people pushed the one meal a day earlier to the noon hour, with various justifications.

Advertisement promoting Hot Cross Buns during Lent. The Ladies’ Home Journal (March 1948). Page 239 (CLICK FOR LARGER) / Internet archive.org / Accessed August 2018 at https://archive.org/stream/ladieshomejourna65janwyet/ladieshomejourna65janwyet#page/n627/mode/1up

The primary items to be avoided were meat, eggs, and dairy. Eggs and milk weren’t on the list of food items to be avoided at first but were by the 800s (you could buy exemptions to allow you to eat them.) [1]”There does not seem at the beginning to have been any prohibition of lacticinia, as the passage just quoted from Socrates would show. Moreover, at a somewhat later date, Bede tells us of Bishop Cedda, that during Lent he took only one meal a day consisting of “a little bread, a hen’s egg, and a little milk mixed with water” (Church History III.23), while Theodulphus of Orleans in the eighth century regarded abstinence from eggs, cheese, and fish as a mark of exceptional virtue. None the less St. Gregory writing to St. Augustine of England laid down the rule, “We abstain from flesh meat, and from all things that come from flesh, as milk, cheese, and eggs.” This decision was afterwards enshrined in the “Corpus Juris”, and must be regarded as the common law of the Church. Still exceptions were admitted, and dispensations to eat “lacticinia” were often granted upon condition of making a contribution to some pious work. These dispensations were known in Germany as Butterbriefe, and several churches are said to have been partly built by the proceeds of such exceptions. One of the steeples of Rouen cathedral was for this reason formerly known as the Butter Tower. This general prohibition of eggs and milk during Lent is perpetuated in the popular custom of blessing or making gifts of eggs at Easter, and in the English usage of eating pancakes on Shrove Tuesday.” Thurston, Herbert. “Lent.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 30 July 2018 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09152a.htm>.

“…The more austere fasters subsisted on one or two meals a week; but many found that cutting back to one repast a day was a sufficient sacrifice. And while many abstained from meat and wine, some ate nothing but dry bread.

Pope Gregory weighed in on this issue as well. He established the Lenten rule that Christians were to abstain from meat and all things that come from “flesh” such as milk, fat and eggs. And fasting meant one meal a day, normally taken in the mid-afternoon.

The prohibition around milk and eggs gave rise to the tradition of Shrove Tuesday or Mardi Gras (French for Fat Tuesday), which is celebrated the day before Ash Wednesday. On this day Christians would feast on the foods they were required to abstain from during Lent — gorging before the fast as it were — and pancakes became a popular meal for using up all the eggs and milk.

Over time, concessions were made to the rules around fasting. In the 12th and 13th centuries, church authorities such as St. Thomas Aquinas accepted that a certain amount of “snacking,” in addition to one meal a day, should be allowed, particularly for those employed in manual labour. Eating fish was eventually allowed and even the consumption of meat and dairy products as long as a pious act was performed to compensate for the indulgence.” [2]Archer, Doug. The history of Lent. The Catholic Register. 12 February 2009. Accessed August 2018 at https://www.catholicregister.org/features/item/12567-the-history-of-lent

There was no restriction on fish, wine or beer.

Consequently, prices on fish would shoot up before Lent, as the mad buying dash began. Even the Church got into the act of making money on fish during Lent. The abbey at Bury St Edmunds levied a toll on all waggons carrying pickled fish from Yarmouth down to London (the route caused them to pass through the Abbey’s lands.) And the abbey at Abingdon charged a toll on every boat or barge that went past it during Lent on the Thames carrying herring for London.

Herring in fact was the dominant fish served. Inland dwellers had to eat red herring sold to them in markets. People living beside rivers, ponds or the sea were luckier, and had a greater variety of fish. It was a good idea for prudent homemakers to buy and dry a lot of herring in the fall, when it was cheap, and set it aside for Lent the next year. It was often served with mustard, to help people choke it down as they became sick of it.

The demand for fish created all kinds of jobs, down to the people making the barrels to store them in, chopping the wood to smoke them, and making rope for the boats.

Some said that the tail of beaver could be eaten, because it was covered with scales and used for moving through water.

The Church would give food dispensations, though, to ill people. In some monasteries, meat was served in the infirmaries, as the sick were exempt from the fasting rules that were applied in the refectories where everyone else ate. At mealtimes, the infirmaries would often be crowded, and the refectories, deserted. The monks of Malmesbury Abbey drew up a guideline in 1293 that at least a quarter of the monks on a rotating basis had to eat in the refectory, lest a chance visit from a zealous church official catch them out by finding a deserted main dining hall and wonder where everyone was.

The only mercy was that Lent came at a time of year when there wasn’t much food to be abstaining from, anyway. There wasn’t much milk, because the cows had birthed calves that needed it, and not much meat, because the meat that had been preserved last fall was mostly gone, and what animals that were still alive were needed to give birth to new ones.

Many wealthy people — or monasteries — rose to the challenge of finding ways to turn fasting into feasting, while still adhering to the rules, through having good, creative cooks. While not breaking the letter of the law, they certainly stretched its spirit, ferreting out each loophole. You could eat dried fruits and nuts, if you had laid any or could afford them (prices for these were at their highest during Lent.) And while pastry couldn’t be bound together with butter, animal fat, or egg, you could use almond milk instead, if you could afford the almonds, or you could make a yeast dough.

You could pay money to get dispensations to be allowed to eat some dairy foods during Lent. A tower that is part of Rouen Cathedral was known as “Butter Tower”, because it was financed with such contributions. The butter dispensations would come to be one of the things that Martin Luther drew attention to when he started the Protestant Reformation with his treatises in 1520.

It being spring, birds are inclined to lay eggs, chickens included. This created the problem of what to do with all the eggs laid during that time. Part of the solution was to kill off and eat up a number of your chickens before Lent began, to reduce the problem. And then, what eggs were laid during that time were preserved in various ways.

During Lent, marrying was also forbidden, the church organs weren’t played, the church altar ornaments were covered, and some churches hung a curtain hiding the entire altar area. Purple cloth was used for curtains, covering and priest’s vestments, as purple is the colour of mourning in the Church.

Lent fasting began in England sometime during the reign of Earconberht, the king of Kent (640 to 664.) During the Middle Ages, until William III, fasting in England was required both by Church law and the law of the land.

In England, a law in 1417 said even that only coarse breads could be baked and sold, not fine wheat breads.

During the English siege of the French city of Orleans in 1429, the people and troops inside the walls started to starve — they had some food that they could eat, but they didn’t, because it was Lent and the foods they had were forbidden. The English sent special convoys carrying fish (herring) to their troops.

Observance started to relax during the Reformation despite efforts to keep it going. Part of the effort to keep Lent observance going was motivated by a desire to keep the demand for fish high: the fish market started to falter as people started to eat meat during Lent. Edward VI, in 1549, reaffirmed that Lent was to be kept, both for moral reasons and to encourage the fish trade. In 1560, Queen Elizabeth decreed a fine for butchers who slaughtered meat during Lent.

A Lent meal of salmon and vegetables. Cattalin / Pixabay.com / 2013 / CC0 1.0

In 1563, Sir William Cecil forced a (Protestant) Parliament to pass a fine of either 3 pounds or 3 months in jail for people eating meat during Lent. His reason is that he felt fishermen, with no trade, were turning to piracy. He added a handwritten codicil to the act assuring the parliamentarians that it was not for religious reasons, but for economic ones. The Puritans, however, were inclined to be very open about flaunting Lent practices (while picking new food restrictions that they wanted to impose on others at times such as Christmas.) Further royal proclamations to observe Lent went out in 1619 and 1625 (by James I), in 1627 and 1631 (by Charles I), and in 1687 (by James II.)

After the English Revolution of 1688, there was no more effort to enforce the state laws on Lent. They were ignored by both the government and the people, and by 1863 they were finally swept from the books by the Statute Law Revision Act.

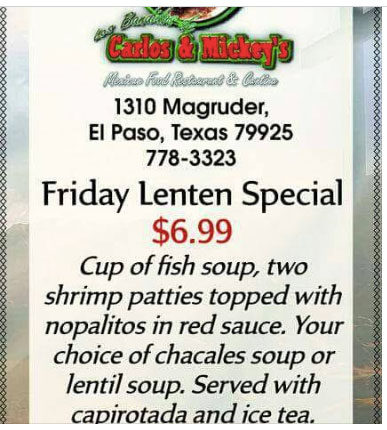

Even in 2017, some restaurants still offer Lent meals. Jan / flickr / 2017 / CC BY 2.0

Mothering Sunday was the fourth Sunday in Lent, half-way through. The Simnel cakes that girls made for their mothers were designed to keep for eating when Lent was over. Some places, though, allowed the eating of the cakes on that day (also called “Laetare Sunday” or “Rejoice Sunday”, from the introit for the service that day, “Rejoice, Jerusalem”.)

In case you’re counting, Lent actually starts about 6 and ½ weeks before Easter — well over 40 days. Sundays are not counted, as they are “celebration” days in the Church. And in the Catholic Church, Lent ends on Maundy Thursday, but then Maundy Thursday, Good Friday and Holy Saturday are fast days in their own right, so no break in the fast actually occurs until a few days later at Easter.

Now, most people observing Lent just choose one food item to give up for Lent, such as chocolate or wine. (Neither of which was on any list of proscribed foods originally.) In 2018, the Church of England called for people to give up plastic for Lent. [3]BBC. Church of England issues anti-plastic tips for Lent. 15 February 2018. Accessed August 2018 at https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43071151

A short fasting period used to happen also before Christmas (perhaps it wouldn’t be such a bad idea to revive it for the sake of our waist lines.) It lasted until Christmas Day; thus the Christmas Eve meal had to be fish.

#Lent

Other fasting holidays: Yom Kippur, Ieiunium cereris

Language Notes

The English word “Lent” is a short form of the full word “Lenten”. It comes from the Old English word “lencten“, which itself comes from an older Germanic wording “langitinaz” meaning long days (as in spring, when the days get longer.)

The Church Latin term for Lent of “quadragesima” is more perhaps more descriptive, meaning literally the “fortieth day”. In Greek, it was “tessarakoste“, again meaning “fortieth”. Another Church — and Jewish — festival was Pentecost — in Greek, “pentekoste” (meaning “fiftieth” — the time between Easter Sunday and Whit-Sunday).

Sources

Godoy, Maria. Lust, Lies And Empire: The Fishy Tale Behind Eating Fish On Friday. National Public Radio. 6 April 2012. Accessed August 2018 at https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2012/04/05/150061991/lust-lies-and-empire-the-fishy-tale-behind-eating-fish-on-friday

Lent. Ecumenical Catholic Communion. Accessed August 2018 at http://www.ecumenical-catholic-communion.org/eccpdf/lent.pdf

Lent. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed August 2018 at https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lent

Spring flowers are one sign of cheer that is always allowed during Lent. Lars Kasper / flickr.com / 2013 / CC BY 2.0

References

| ↑1 | ”There does not seem at the beginning to have been any prohibition of lacticinia, as the passage just quoted from Socrates would show. Moreover, at a somewhat later date, Bede tells us of Bishop Cedda, that during Lent he took only one meal a day consisting of “a little bread, a hen’s egg, and a little milk mixed with water” (Church History III.23), while Theodulphus of Orleans in the eighth century regarded abstinence from eggs, cheese, and fish as a mark of exceptional virtue. None the less St. Gregory writing to St. Augustine of England laid down the rule, “We abstain from flesh meat, and from all things that come from flesh, as milk, cheese, and eggs.” This decision was afterwards enshrined in the “Corpus Juris”, and must be regarded as the common law of the Church. Still exceptions were admitted, and dispensations to eat “lacticinia” were often granted upon condition of making a contribution to some pious work. These dispensations were known in Germany as Butterbriefe, and several churches are said to have been partly built by the proceeds of such exceptions. One of the steeples of Rouen cathedral was for this reason formerly known as the Butter Tower. This general prohibition of eggs and milk during Lent is perpetuated in the popular custom of blessing or making gifts of eggs at Easter, and in the English usage of eating pancakes on Shrove Tuesday.” Thurston, Herbert. “Lent.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 30 July 2018 <http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/09152a.htm>. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Archer, Doug. The history of Lent. The Catholic Register. 12 February 2009. Accessed August 2018 at https://www.catholicregister.org/features/item/12567-the-history-of-lent |

| ↑3 | BBC. Church of England issues anti-plastic tips for Lent. 15 February 2018. Accessed August 2018 at https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-43071151 |