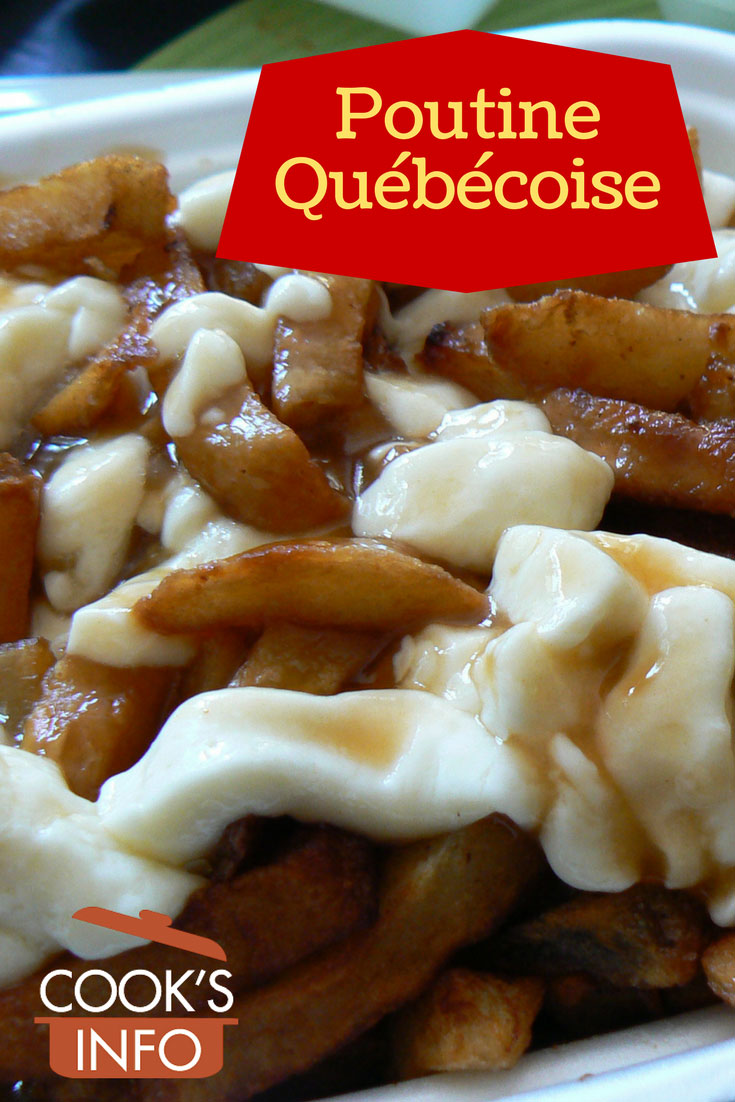

Poutine Québécoise. Sjschen / wikimedia / 2007 / CC BY 3.0

Poutine as served in Québec is a fast food, consisting of French fries, covered with cheese curds, then thick, dark gravy. The cheese and gravy form a gooey mass, while the fries underneath stay crunchy. The dish is served in styrofoam dishes and eaten with plastic forks. It has to be eaten as soon as it’s made; the texture isn’t as good if reheated.

Popular fast food

Poutine is made and sold throughout Quebec. It first appeared in “burger and hotdog” type places. Sometime in the early 1990s it began appearing at fast-food chain restaurants, and then, in fancier restaurants with “gourmet takes” on it. Despite that, many aficionados still say that street vendors make the best poutine. You can also get it even at a few places in Florida, in places where high concentrations of Québécois spend the winter.

Despite people’s joking health reservations about the dish — that the only thing missing is a spoonful of lard on top — poutine remains a prized food after a night of heavy drinking or clubbing. And perhaps it looks better at that time of night: even the most ardent fan will admit that it is very hard to photograph poutine to make it look as good as it tastes.

Purists say the fries should actually be what the Brits would call “chips” — thick, chunky potato wedges, and not frozen ones at that, either, but freshly cut and fried on the spot, preferably in lard, and dished up when still piping hot.

The cheese curds used are white cheddar ones, which in consistency are somewhat like a cross between American-style mozzarella, and white cheddar. The cheese curds should be so fresh that they squeak as you bite into them, and feel with every bite as though they are cleaning your teeth. If the curds are old, they will just be rubbery, instead and not give the right consistency when the heat hits them. The curds should not smell cheesy. They are put on top of the fries as is, and will only partially melt from the heat of the assembled dish.

Tinned Poutine Sauce. © Denzil Green / 2008

There are, of course, better and worse qualities of gravy that you can use. Though any meat gravy will do, you can buy powdered gravy mixes or canned prepared gravy sold specially as “poutine gravy.” Many people prefer the gravy sold by the restaurant chain in Quebec called “St-Hubert.”

You don’t usually put ketchup on top, though some English-speakers do.

Many poutine variations are now being offered. In Rimouski, Québec, a version is made that includes mayonnaise as well. If it’s with Bolognese sauce instead of gravy, it’s called Italian poutine. With just fries and gravy (no cheese), it is not poutine, but called “patates-sauce” instead. With chicken and peas added, it’s called “galvaude.” Gourmet poutines are made using Camembert or blue cheese instead of the cheese curds. Some chefs serve poutine in their bistros, with foie gras on it, and instead of just gravy, a sauce with cream, meat stock and egg yolk in it. There are also vegetarian versions.

Until the early 2000s, poutine was largely unknown in other parts of Canada, except for those tourists from elsewhere in Canada who had spent time in Quebec and started looking for the dish back home. It was around that time that some fast-food chains began putting it on their menus, and marketing it outside Quebec, portraying it as a national “Canadian” dish. The advantage to listing poutine on the menu was that it had a relatively large price markup compared to just plain French fries. Within 15 years, many Canadians — anxious for a food they could call their own — had embraced poutine as the iconic Canadian dish.

The town of Maillardville, British Columbia, holds a Poutine Festival every year.

Some Quebecois now feel that poutine has been “culturally appropriated” by the rest of Canada who now call it Canada’s national food. They say it’s like saying pizza is Canadian, instead of Italian. They say that poutine is Québec’s national dish — not Canada’s. (And don’t forget that in French, Quebec is termed a “nation.”)

Poutine is, however, so similar to dishes served elsewhere in North America, and in the UK, such as Gravy Fries, Cheese Fries and Disco Fries, that it’s hard not to look on it as a “fusion food” from surrounding English areas. Both Gravy Fries and Cheese Fries, served in the U.S., predate poutine by several decades. In many diners in the north-eastern American states near to Québec, you’ll see on menus plain fries, cheese fries or gravy fries. Poutine differs from Disco Fries, which some Americans look on as “ghetto food”, in the cheese being used: with poutine, it has to be white cheddar cheese curds.

And, don’t forget, that just a bit further east, in the French-speaking Acadian regions of Canada, poutine is a completely different dish, and has been made for far longer than the Quebecois version.

History Notes

A man named Fernand Lachance (27 Aug 1917 – 7 Feb 2004) claimed to have invented Poutine in 1957 at a restaurant he worked at called “Le Lutin Qui Rit” (“The Laughing Imp”) and then later at his own restaurant “Café Ideal”, in Warwick, Québec. He said that it was a trucker, a Jean Guy (aka Eddy) Lanaisse, also a resident of Warwick, who gave him the idea. Lanaisse ordered fries, but had seen the cheese curds being sold separately on the restaurant counter. Lanaisse asked for them together. Lachance warned him that it would be a “poutine”, which means “a mess”, but Lanaisse found it very tasty.

After that, Lachance started offering cheese curds on top of fries for 35 cents. Customers would dress it up with ketchup. The gravy idea came later in 1964, when he realized that the hot gravy would help to melt the cheese more. So he added gravy, and hiked the price to 60 cents. Lachance’s wife Germaine made the gravy. It was actually more of a barbeque sauce, whose ingredients included brown sugar, ketchup and Worcestershire sauce.

Other towns in Québec such as Drummondville and Victoriaville also claim to be its home. In Drummondville, Jean-Paul Roy (1932 – ) , owner of Roy le Jucep restaurant, claims to have invented Poutine together with his wife Fernande in 1964. They first owned a restaurant called “Le Roi de la patate”. In 1964, they opened a new restaurant called “Roy le Jucep”. At first, they sold just “patates-sauce” — gravy and fries. The gravy was served on the side in a little cup, because the fries were in a cardboard box that would have got soggy. The cheese curds were in a bag, just another item on the menu. Then some customers came in, and asked for them mixed into their patates-sauce, as they were eating in their car, and space on their laps would have been limited. More customers asked for the combination, so they put it on the menu as an official menu item. Jean-Paul and Fernande called it just “fromage, patate, sauce”. They decided eventually to call it “Poutine” because pudding (the real meaning of “Poutine”; see Language Notes below) could really be anything you wanted to call pudding. As well, Poutine ended up being a reverse play on the name of one of their cooks at the time, a man named “Ti-Pout” (pronounced tee-pooh.) So, “tee-pooh” made the “pooh-teen”. Roy sold the restaurant in 1985 at the age of 53. The restaurant is still in business today (2007.)

Some Acadians say the Québécois version was in fact invented in New Brunswick, at a take-out restaurant near Parlee Beach in Shediac, New Brunswick, and that the idea was taken back to Québec by tourists.

Language Notes

Pronounced “pooh – teen”, though purists of Québecois pronunciation will insist that you give “t” a “ts” sound (as in “tsar” — what linguists term “an affricated dental stop”) before soft vowels, and shorten the E sound at the end, making it “pooh – tsin”.

Poutine was used as the name for other dishes long before it was applied to this one.

Poutine is referred to in 1812 in a listing of household goods in a Québec will as being something you would cook in a mould: “deux moules à poutins & une passoire”. In 1916, there is a reference by Hector Berthelot in his “Montréal: le bon vieux temps” to “poutine glissante”, the Acadian dish. In the 1930s, Poutine was used as a direct translation of the English word pudding (in the North American sense, not the general British sense of “dessert”). Rice pudding was called “poutine au riz”. In 1971, Louise Lavoie in her “La cuisine chez nos grands-mères” gives a recipe for “poutine à vapeur” (steamed pudding), and throughout the 1970s, Poutine was still used in the sense of something you would have for dessert: “Je vais vous faire de la poutine pour dessert.” (I am going to make some poutine for dessert.)

Only by 1980 do you start to see the word used in the sense it is now, that of cheese fries with gravy:

“Quand j’t’allé au restaurant, y m’ont servi une poutine dégeulasse; les patates frites étaient pas cuitent, la sauce était claire comme de l’eau pis l’fromage avait l’goût de moisi.” (When I went to the restaurant, they served me a disgusting poutine: the fries weren’t cooked, the sauce was as clear as water, and the cheese tasted like mildew.) (Cited in: Fournier, Serge, et Poirier, Étienne, (dir.), 1973- x: Corpus du Centre d’études de linguistique de la Mauricie, Shawinigan.)

But the old usage of poutine referring to a sweet dessert dish was still prevalent in 1980: “Quand ma tante des États-Unis à venait, on disait d’la pouding, mais sinon c’tait toujours de la poutine.” (When my aunt came from the states to visit, we said “pouding”, but it was still just poutine.” (Ibid.)

Today, when you hear poutine in Québec, you can generally assume it is the cheese fries with gravy. But if the word is used in the context of dessert, or is qualified such as “aux raisins”, then it will be another dish entirely.

Poutine was also used colloquially in Québec to mean “a mess.”

The word itself has an amusing history. It comes from an old French word, “boudin“, which English borrowed and transformed into “pudding.” Along the way, French borrowed the word back, transforming it into “poutine”.

Larousse Gastronomique (1988, English version, page 842) gives another version; it says that “poutine” comes from the Provençal word “poutina”, meaning “porridge”. In any event, both “boudin” and “poutina” would both no doubt be descendants of a common ancestor word.

Sources

CTV.ca News Staff. ‘Mr. Poutine’ remembered for inventing an icon. 12 February 2004. Retrieved from http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/1076633168163_72042368 October 2005.

Krauss, Clifford. Québec Finds Pride in a Greasy Favorite. New York Times. 26 April 2004.

McGimpsey, David. In search of the premier poutine. The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Canada. Saturday, 12 June 2004.

McGimpsey, David. French fries, cheese and gravy. What’s not to love? The Globe and Mail. Toronto, Canada. 12 June 2004.

Roy, Jean-Paul. J’ai inventé la poutine! In an interview conducted for Roy Jucep restaurant. Retrieved October 2006 from http://www.jucep.com/inventeur/francais/index.html