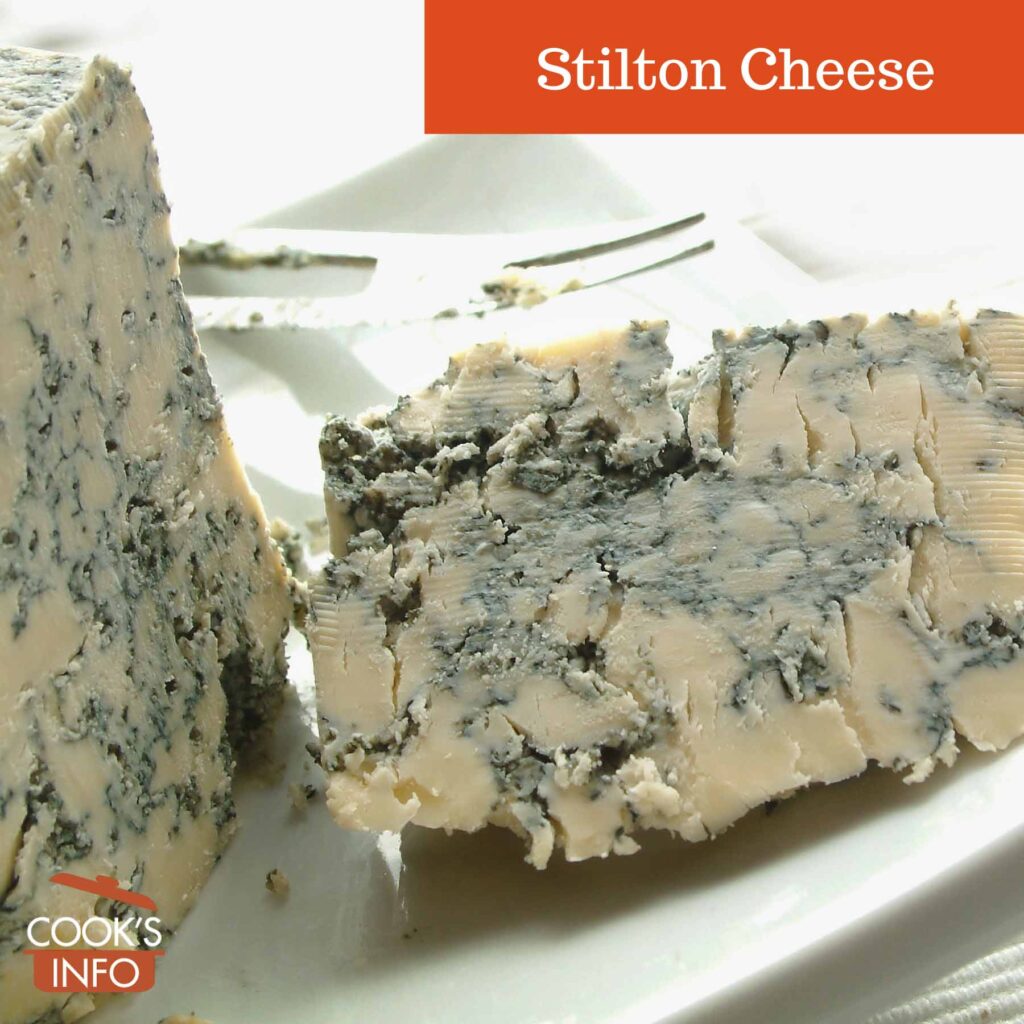

Stilton is an English blue cheese whose powerful, pungent taste is stronger than Roquefort and Gorgonzola. Its texture is both crumbly and creamy.

Stilton is a European PDO-protected cheese. [1]By treaty, this protection has continued even after Brexit.

Production

Cow’s milk is pasteurized first at 72 C (161 F) for 15 seconds. The milk is then cooled down to 30 C to 31 C (86 F to 88 F). Penicillium roqueforti and rennet are added. The milk is allowed to curdle for an hour to an hour and a half. Then the curd is cut, allowed to settle for another 1 ½ hours, then drained overnight.

The next morning it is salted and placed in cylindrical moulds. For the next 10 days, the moulds are turned daily. The cheese is then removed from the moulds, and its surfaces scraped and rubbed to even them. It’s then let stand for about a week for mould to grow on the surface, then transferred to a ripening room. After 4 – 6 weeks of aging, the cheeses are pierced with needles to allow air in for the interior mould to grow. The cheese is ready to eat at 3 months old.

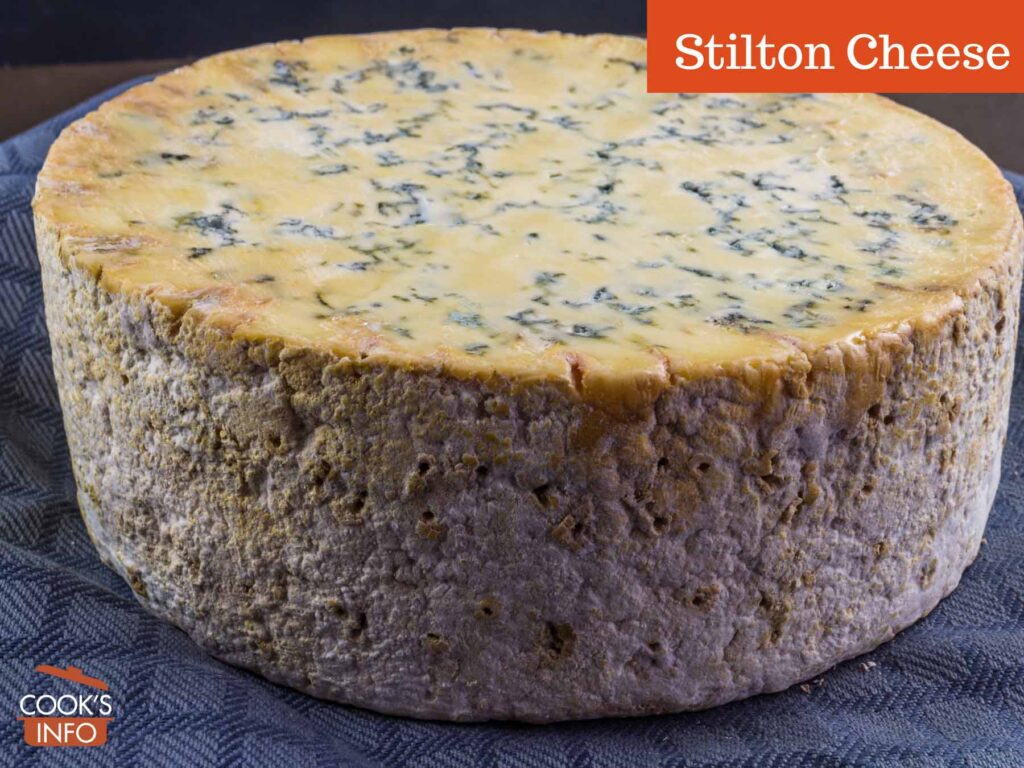

The scraping of the cheese’s surface, done by hand, helps to give the cheese its crust, which turns out brown and wrinkled, and is edible.

Stilton is always made in a cylinder shape. All Stilton is now made in cheese factories. Only six dairies (or seven, depending on who you read) in the three English counties of Derbyshire, Leicestershire, and Nottinghamshire are allowed to make Stilton.

Purchasing Stilton

Choose Stilton cheese with a rough, dry rind. The centre should be creamy without being crumbly — if the centre is crumbly, the cheese is drying and needs to be used up.

Crockery jars filled with Stilton (known as “Stilton pots”) are filled with pieces of broken Stilton. The quality of the cheese in them isn’t as good as a piece of Stilton — after all, you are paying for the “cute” collectible pot. BBC Food at one pointed deemed the top four pots to be Fortnum and Mason, Harrods, Webster’s, and Cropwell.

Cooking Tips

Crumble some Stilton on top of soups, particularly cream soups such as celery or mushroom.

Equivalents

1 cup, crumbled ≈ ¼ pound ≈ 115 g

Storage Hints

Store refrigerated for up to a month, wrapped tightly in tin foil. To freeze, wrap first in plastic wrap, then in tin foil.

History Notes

In the town of Stilton, in 1730, a Mr Cooper Thornhill owned a public house called the Bell Inn on the Great North Road. It was a good spot for the Inn, as travellers going north from London went along this road and stopped at the Inn. It was about 70 miles north (110 km) of London, which made it the first stop after a day’s travel from London going north by coach or horse.

While visiting a small farm in Lancashire, he tasted a blue cheese that he loved, and worked out a deal to give his inn the rights to distribute it. He promoted and sold the cheese at the Inn, and travellers from both the north and the south raved about it. He also sold it in the market at Melton Mowbray. Even though the cheese wasn’t made in Stilton, it was still called that as that’s where the cheese was supplied from.

A woman named Frances Pawlett made the best Stilton, and organized others at setting standards for the cheese. Thornhill worked with Frances Pawlett and her husband to promote the cheese.

Production was halted during World War Two:

Production was halted during World War Two:

“The blue-veined cheeses — Stilton, Dorset Blue and Blue Wensleydale — are also in part mould-flavoured, but their manufacture is also prohibited during the war.” [2]How Butter and Cheese are Made. London, England: Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. Friday, 1 September 1944. Page 133, col. 1.

Stilton was made from raw milk until 1989:

“Notoriously, in 1989, Stilton cheese effectively became extinct following a health scare. The Milk Marketing Board leaned on Colston Bassett, the farm cooperative that was the last producer of raw-milk Stilton, to buy expensive pasteurisation equipment. Worse, the Stilton Cheesemakers’ Association successfully lobbied to alter the definition so that “Stilton” had to be made from pasteurised milk. You may remember pre-pasteurised Stilton. It was fruitier, creamier, moistly unctuous and buttery, not crumbly in the middle. Now, such a cheese is once more being made – it just can’t be called “Stilton”. If you look for “Stichelton” online, or at the cheesemonger, you’ll be astonished.” — Levy, Paul. A bouquet of sweet hay and clover? It must be real milk. London: Daily Telegraph. 24 July 2014.

Literature & Lore

The first written reference to Stilton dates back to 1722 in William Stukeley’s “Itinerarium Curiosum”.

“There, too, another English returnee, the well-known St. Ivel’s English Stilton, double cream, blue-veined, semihard. Eight years since the last Stilton shipment.” — Paddleford, Clementine (1898 – 1967). Food Flashes Column. Gourmet Magazine. February 1949.

Sources

Jones, Jerene. Stilton Is the Blue Cheese of Blue Bloods. People Magazine. Vol 18, No 22. 29 November 1982.