Ground sumac. © CooksInfo / 2011

Sumac is a red or purplish-red powdered spice made from the berries and occasionally the leaves of the sumac bush.

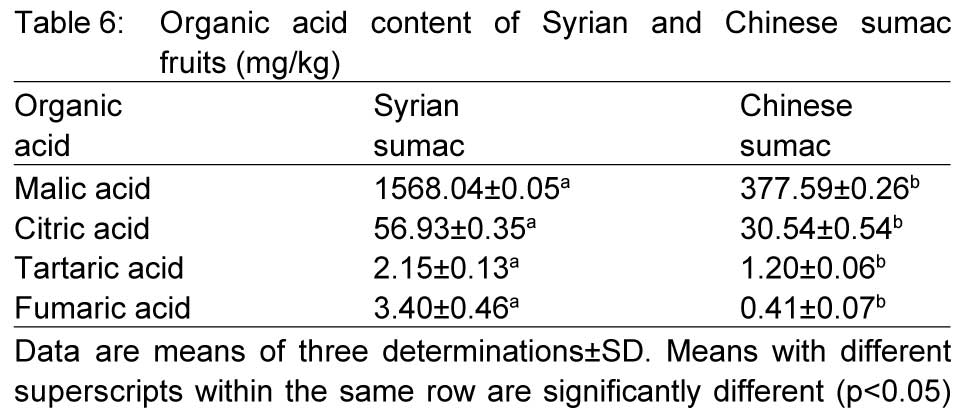

It has a tart, lemony taste and smell that comes from malic acid on the sumac berries. It is not, though, as sour as lemon or vinegar.

It has long been used to balance flavours in dishes by adding sour notes:

“The acid fruits are used as a sour flavouring. They were so used in classical Rome, before the introduction of the lemon, and their modern use in the Middle East is most noticeable in areas where lemons are rare, for instance the remoter parts of Syria and Northern Iraq.” [1]Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 924.

The berries are referred to as berries, though they are not true berries.

Sumac cultivation

Sumac grows both wild and under cultivation. There are many different varieties — you will see numbers ranging from 35 to 250, depending on how tightly the writer wants to define the scope. Most varieties either grow wild or are grown as an ornamental or don’t produce berries flavourful enough to be considered worthwhile trying to use.

Larousse Gastronomique says:

“A shrub originating in Turkey, certain varieties of which are cultivated in southern Italy and Sicily…. Varieties of sumac cultivated in Britain are ornamental and not used in cookery.” [2]Lang, Jennifer Harvey, ed. Larousse Gastronomique. New York: Crown Publishers. English edition 1988. Page 1036.

Sumac is also grown and used in the Middle East, particularly northern Iran. [3]”The distribution of the plant is scattered, mostly on foothills of many parts of northern Iran, such as Azerbyjan, Qazvin, Albourz and Khorasan.” Matloobi, M. and Tahmasebi, S. (2019). Iranian sumac (Rhus coriaria) can spice up urban landscapes by its ornamental aspects. Acta Hortic. 1240, 77-82

. https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2019.1240.13

Sicilian sumac (aka Syrian sumac, aka Iranian sumac, aka Rhus coriaria) is considered by many to be amongst the best flavoured.

Sumac bushes will grow from seed, root cuttings, or suckers. The berries grow in clumps and are ready for harvest in late summer and early fall.

Harvesting sumac berries

The berries have velvet-like hair on them. The tartness is in the hairs. Most of the flavour is on the surface of the skin. A white sticky substance on the red berries is fine: that’s the malic acid which gives the sour taste.

The berries are picked when they are fully ripe, generally a dark reddish-purple, but before rain has had a chance to wash the flavour off them. If the berries are harvested before they are ripe, they will be bitter. If harvested after a rainfall, their flavour will be washed away.

After they are picked they are dried, then ground.

When dried berries are ground into a powder, the powder doesn’t have much aroma, but has flavour.

North American sumacs

There are several varieties of sumac native to North America that are edible.

Smooth sumac berries. USDA / wikimedia / 1996 / Public Domain

The most common ones are “Smooth Sumac, Rhubs glabra; Staghorn Sumac, R. thyphina; and Winged or Dwarf Sumac, R. Copallina.” [4]Frankel, Edward. Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, Poison Sumac and Their Relatives; Pistachios, Mangoes and Cashews. Pacific Grove, California: Boxwood Press. 1991. Page 42.

Winged sumac berries. Riverbanks Outdoor Store / wikimedia / 1980 / CC BY 2.0

Another less common edible variety emits an aroma which people either love, or hate:

“The fourth and rarest member of the local safe sumacs is Rhus aromatica, Aromatic or Fragrant, Lemon or Polecat Sumac…. Aromatic Sumac is a short shrub which bears spikelike clusters of yellow flowers about the time the leaves appear. When crushed the leaves emit a very distinct aroma which some people find pleasant and others offensive. In summer, it flashes clusters of fuzzy, upright red fruits, the safe sumac signal.” [5]Frankel. Page 43-44.

Aromatic sumac berries. Salicyna / wikimedia / 2016 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Another variety, Rhus integrifolia, known as “Lemonade Berry Sumac”, is native to Southern California and Baja Mexico. Its berries ripen to pinkish-red, and can be used to make a lemonade-flavoured drink. [6]Lemonade Berry. Sumac. Better Homes and Garden Plant Dictionary. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.bhg.com/gardening/plant-dictionary/shrub/sumac/

Lemonade Berry Sumac. Docent joyce / wikimedia / 2015 / CC BY 2.0

The fruit of all these grows at the end of branches.

Of these varieties, smooth sumac and staghorn sumac appear to be the most common, and staghorn is the tarter of the two.

While staghorn is not identical to European sumacs, it has berries with an extremely similar taste.

Staghorn sumac on bush. © CooksInfo / 2013

Poisonous variety of sumac

In North America, there is also a poisonous variety of sumac which would-be nature harvesters must be on the alert for.

This variety has white berries that grow along the stem, and hang in clusters, like teeny white grapes. This variety is called Toxicodendron vernix (previously called Rhus vernix).

Edward Frankel, author of “Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, Poison Sumac and Their Relatives”, writes:

“In the northeastern United States and Canada there are several nonpoisonous sumacs that are easily and frequently mistaken for Poison Sumac. Three of the most common [safe] species are shrubs with pinnately compound leaves that resemble the foliage of their caustic cousin. They are Smooth Sumac, Rhubs glabra; Staghorn Sumac, R. thyphina; and Winged or Dwarf Sumac, R. Copallina. This nontoxic trio, which is far more common the Poison Sumac, grows along roadsides, dry woods and clearings in sprawling communities. Unfortunately, they cross paths with Poison Sumac and the common grounds on which they meet is where the danger lurks. The easiest way to tell the “safe” from the “sinister” sumacs is by their fruits, which appear in late summer and fall. The “safe” sumacs wear red hats, conspicuous clusters of reddish fruits at the ends of upturned branches, hard to miss. The “sinister” sumacs bear loose bunches of hanging white to gray fruits along the stems.” [7]Frankel. Page 42.

Poison sumac. James H. Miller & Ted Bodner / wikimedia / 2005 / CC BY 3.0

Frankel says, though, that it is very easy at harvest time to tell the difference between the safe and the poisonous North American sumac berries:

“When all is said and done, ‘by their fruits ye shall know them’, that is, the safe sumacs by upright terminal clusters of red fruits and the troublesome Toxicodendrons by axillary drooping bunches of whitish drupes.” [8]Frankel. Page 44.

Cooking tips

Sumac provides a way to add sourness to a dish in a dry form. Otherwise, adding sourness typically requires adding something liquid such as vinegar, or lemon juice.

Sumac is used in cooking in Iran, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey and Sicily. Shakers of sumac flakes are put on tables on restaurants in the Middle East, and it is used in making za’atar.

Larousse Gastronomique says:

“Mixed with water, it can be used in the same way as lemon juice, particularly in preparations of tomatoes and onions, chicken forcemeats, marinades of fish, and dishes with a lentil base.” [9]Lang, Jennifer Harvey, ed. Larousse Gastronomique. New York: Crown Publishers. English edition 1988. Page 1036.

Sumacade

Red berries from sumac native to North America are mostly used to make a lemonade-type drink that some call it “sumac-ade.” For a pitcher of pink lemonade, use 6 to 8 clusters of berries. You pour boiling water over the berries, allow to stand for 15 minutes, squeeze the berries, then strain out through cheesecloth and discard the berries, then sweeten the juice to taste.

For less tannin in the drink, instead of hot water, soak in cold water overnight.

A juice can be also made from dried berries, and used in cooking.

Substitute

For a dry souring agent, try citric acid. If liquidity doesn’t matter then, lemon juice or vinegar.

Nutrition

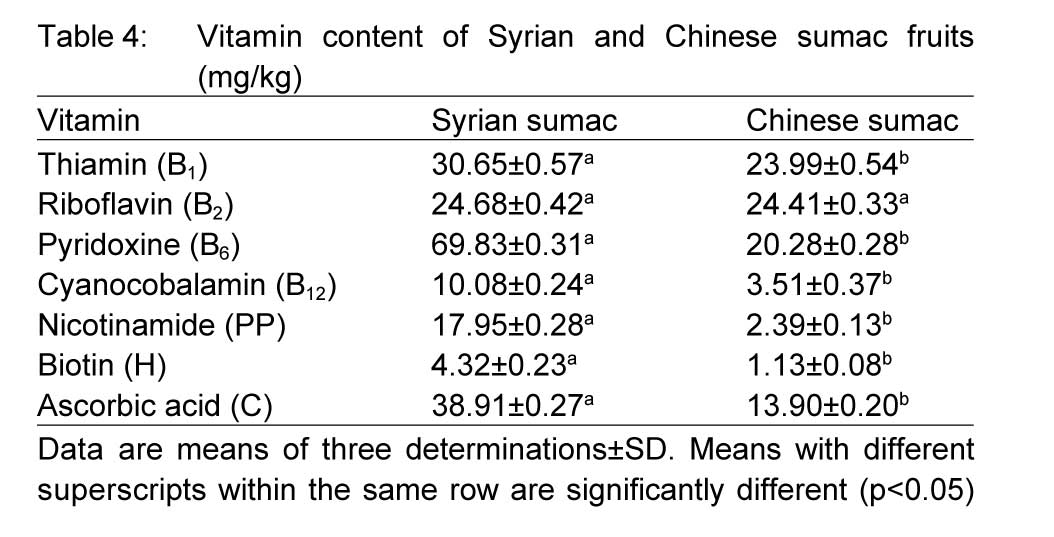

Sumac is not a particularly rich source of Vitamin C, as is often mistakenly said even by usually reputable sites such as U.S. university extension service sites.

Sumac has at its estimated highest levels about 3.9 mg of Vitamin C per 100 g. (Amount varies by variety.) Compare this with an orange, which has 53.2 mg per 100 g. Even cabbage has nearly ten times more, at 36.6 mg per 100 g. (Source: USDA). An adult would have to consume several pounds of sumac daily to meet the recommended U.S. daily Vitamin C amount. [10] Rima Kossah et al. Comparative Study on the Chemical Composition of Syrian Sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) and Chinese Sumac (Rhus typhina L.) Fruits. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 8 (10): 1570-1574, 2009. Page 1572.

Chart above shows amounts per 1000 g. Source: Rima Kossah et al. Comparative Study on the Chemical Composition of Syrian Sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) and Chinese Sumac (Rhus typhina L.) Fruits. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 8 (10): 1570-1574, 2009. Page 1572.

As stated earlier, the sourness of sumac comes from malic acid, not ascorbic acid, of which sumac has only trace amounts. This table shows the incredible high amounts of malic acid in sumac.

Chart above shows amounts per 1000 g. Rima Kossah et al. Page 1573.

Anyone allergic to cashew nuts or mangos may be allergic to sumac.

Don’t even touch or brush against poison sumac: just touching it can cause skin irritation, rashes and severe dermatitis. Do not inhale the vapours of poison sumac bushes being burnt. Animals are not affected by the poison and eat the berries in the winter.

Equivalents

½ cup = 65 g = 2.3 oz

1 tablespoon = 10 g

History Notes

Sumac is native to parts of the Mediterranean such as southern Italy, and to the Middle East, and to North America.

The Romans used sumac juice and powder used as a souring agent.

Native Americans would gather red sumac berries, and dry them for food over the winter. They also used various parts of the plant for many other purposes:

“Native Americans… made a rinse from boiled berries [that] was applied to stop bleeding after childbirth. Tea prepared from leaves was used to treat asthma and diarrhea. Roots were boiled to extract an antiseptic applied to wounds and ulcers. Juice extracted from roots was believed to cure warts. Tea prepared from green twigs was used to treat tuberculosis… A surprising range of pigments were extracted from sumac for dyeing baskets and blankets. Navajo used fermented berries to create an orange-brown dye, while a different extraction from berries produced red. Crushed twigs and leaves yielded a black dye when mixed with ochre mineral and the resin of pinyon pine. Roots produced a yellow dye and a light-yellow dye could be made from the pulverized pulp of stems. Tannins extracted from leaves produce a brown dye.” [11]Mitton, Jeff. Smooth sumac has edible berries and poisonous but medicinal leaves. Colorado Arts and Sciences Magazine. 7 January 2020. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine/2020/01/07/smooth-sumac-has-edible-berries-and-poisonous-medicinal-leaves

Language Notes

Also spelt “sumach”.

From the Arabic word “summaq.”

Staghorn sumac berries. Posed with U.S. nickel to show scale. © CooksInfo / 2013

References

| ↑1 | Davidson, Alan. The Penguin Companion to Food. London: The Penguin Group, 2002. Page 924. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lang, Jennifer Harvey, ed. Larousse Gastronomique. New York: Crown Publishers. English edition 1988. Page 1036. |

| ↑3 | ”The distribution of the plant is scattered, mostly on foothills of many parts of northern Iran, such as Azerbyjan, Qazvin, Albourz and Khorasan.” Matloobi, M. and Tahmasebi, S. (2019). Iranian sumac (Rhus coriaria) can spice up urban landscapes by its ornamental aspects. Acta Hortic. 1240, 77-82 . https://doi.org/10.17660/ActaHortic.2019.1240.13 |

| ↑4 | Frankel, Edward. Poison Ivy, Poison Oak, Poison Sumac and Their Relatives; Pistachios, Mangoes and Cashews. Pacific Grove, California: Boxwood Press. 1991. Page 42. |

| ↑5 | Frankel. Page 43-44. |

| ↑6 | Lemonade Berry. Sumac. Better Homes and Garden Plant Dictionary. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.bhg.com/gardening/plant-dictionary/shrub/sumac/ |

| ↑7 | Frankel. Page 42. |

| ↑8 | Frankel. Page 44. |

| ↑9 | Lang, Jennifer Harvey, ed. Larousse Gastronomique. New York: Crown Publishers. English edition 1988. Page 1036. |

| ↑10 | Rima Kossah et al. Comparative Study on the Chemical Composition of Syrian Sumac (Rhus coriaria L.) and Chinese Sumac (Rhus typhina L.) Fruits. Pakistan Journal of Nutrition 8 (10): 1570-1574, 2009. Page 1572. |

| ↑11 | Mitton, Jeff. Smooth sumac has edible berries and poisonous but medicinal leaves. Colorado Arts and Sciences Magazine. 7 January 2020. Accessed July 2020 at https://www.colorado.edu/asmagazine/2020/01/07/smooth-sumac-has-edible-berries-and-poisonous-medicinal-leaves |