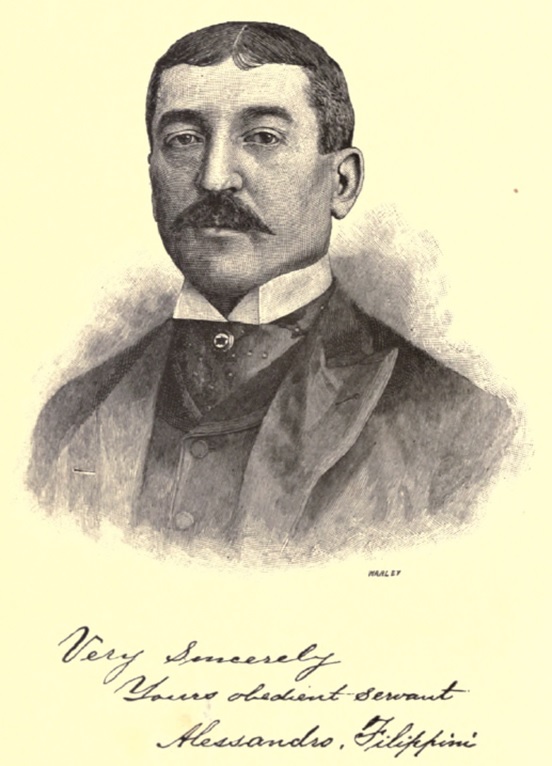

Alessandro Filippini. From The Table. 1889 edition.

Alessandro Filippini (31 December 1849 – 8 December 1917) was a chef at Delmonico’s Restaurant in New York in the second half of the 1800s, and a cookbook author. He anglicized his name and operated professionally as “Alexander Filippini.”

Louis Fauchère, another chef at Delmonico’s, is said to have trained under him.

See also: Delmonico’s Restaurant

Early years

Filippini was born in Airolo, Switzerland, a town at the very north end of the Swiss canton of Ticino (the same canton that the Delmonico Restaurant family came from.) Today, Airolo is the southern end of the St Gotthard Road Tunnel under the alps (the north end is at Göschenen in Uri canton.) He came to be very proficient in English, and though he was Italian speaking, he decidedly saw himself as Swiss as opposed to Italian.

Arrival at Delmonico’s

Filippini was hired by Delmonico’s in New York in 1849 by Lorenzo Delmonico. At the time, Delmonico’s had just one restaurant, at 2 South William Street. By 1884, Filippini was manager and “chef de cuisine” at their second restaurant on Pine Street. Several sources mention that Filippini left Delmonico’s in 1863; if he did, it was only for a short time, as he was at his post in the Pine Street restaurant in 1864.

In 1880, while still working at Delmonico’s, Filippini published his first cookbook: “The Delmonico Cookbook.”

Filippini retired from active restaurant work in 1888, when Delmonico’s Pine Street restaurant was closed, and dedicated himself to writing more cookbooks.

“[Filippini] from Delmonico’s kitchen had progressed to management of the lower Broadway restaurant. When that branch was discontinued, in the late Eighties (to be succeeded by the Café Savarin), Filippini embarked upon a successful career as a compiler of cookbooks and food consultant to railway and steamship lines.” [1]Lately, Thomas. Delmonicos: A Century of Splendor. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. 1967. Page 261.

In the same year, he wrote a letter to Charles Constant Delmonico to ask if he could dedicate his book, “The Table”, to the family. He wrote: “Having been with the “Delmonico’s” for nearly a quarter of a century . . . ” [2]Lately, Thomas. Delmonico’s: A Century of Splendor. Page 261.In 1888, he had in fact been with Delmonico’s for 39 years, but if he were counting from an 1864 return to the restaurant, that would make nearly the quarter of a century that he referred to.

From The Delmonico Cook-Book (1889). Wikipedia / Public Domain

At some point after retiring from the daily demands of Delmonico’s, Alessandro secured a position as Travelling Inspector of the “International Navigation Company” (renamed to International Mercantile Marine Company in 1902.) In his introduction to his 1906 book, “The International Cook Book”, he writes:

“At the time of the publication of my first work, “The Table,” in 1889, my duties and responsibilities at Delmonico’s were such that I was only able to write at irregular intervals, and so the book was necessarily somewhat hurried and contained many reference numbers. It, however, was remarkably successful, through the kind and generous support of the public, for which I am profoundly grateful. This new work, “The International Cook Book,” is the result of years of preparation. No efforts were spared in seeking information from every source. A leave of absence for several months was obtained from my superiors of the International Navigation Company, a tour of the world was made, and personal visits paid to hotels, restaurants and homes of all countries.” [3]It’s unclear why he refers to “The Table” as his first book, as that was “The Delmonico Cookbook.”

In his cookbooks, Filippini gives precise measurements (many cookbooks of the time were still giving imprecise, general measurements.) His books were published under his anglicized name, Alexander Filippini.

Helping him in writing “The International Cook Book” was Louis Lescarboura, who had worked at the Hotel Marlboro. [4]”Louis Lescarboura Dies.” Oxford, Pennsylvania: Chester County Press. 3 March 1971. Page 1.

Books by Alexander (Alessandro) Filippini

- 1880 — The Delmonico Cookbook

- 1888 — La Table: How To Buy Food, How to Cook It, and How to Serve It. Republished 1889, 1890, 1891, 1892, 1895. In contrast to Charles Ranhofer’s later book, “The Epicurean (1894)”, which gave complex recipes from Delmonico’s, Filippini sought to simplify the dishes for the home cook. It wouldn’t be the lady of the house who was doing the cooking, though: this was for well-to-do people who had cooks, many of whom were immigrant girls who had only the most basic of cooking skills. One suggested weekday home dinner menu includes venison with Colbert sauce, sweetbreads à la Pompadour, roast ducks and omelettes soufflées for dessert. ( on Googlebooks )

- 1892 — 100 Ways of Cooking Eggs. ( on Googlebooks )

- 1892 — 100 Ways of Cooking Fish. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co. ( on Googlebooks )

- 1893 — 100 Desserts. New York: Charles L. Webster & Co. ( on Googlebooks )

- 1906 — The International Cook Book ( on Googlebooks )

References

| ↑1 | Lately, Thomas. Delmonicos: A Century of Splendor. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. 1967. Page 261. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Lately, Thomas. Delmonico’s: A Century of Splendor. Page 261. |

| ↑3 | It’s unclear why he refers to “The Table” as his first book, as that was “The Delmonico Cookbook.” |

| ↑4 | ”Louis Lescarboura Dies.” Oxford, Pennsylvania: Chester County Press. 3 March 1971. Page 1. |