Hot Cross Buns. © Julie Brazier/ morguefile.com

Hot Cross Buns are round, slightly-sweet individual serving-sized buns made from a yeast-risen wheat dough with dried fruit in it. They are very deeply browned, and have the form of a cross on top.

Hot Cross Buns are still used in many Easter ceremonies in England (they are not a Scottish, Welsh or Irish tradition.) Not all of the ceremonies are necessarily strictly religious, either.

See also: Hot Cross Buns Day, Hot Cross Buns Recipe

Composition of Hot Cross Buns

The dough has egg in it, as well as spices such as allspice, cinnamon, cloves and nutmeg. Posher ones might even have a small amount of saffron in them. Dried fruit used can include currants, sultanas, raisins, and candied peel. Soaking the fruit in a sugar syrup first can help you end up with a moister bun. This stops the fruit from drawing moisture in from the crumb after baking which can make the bun drier.

The cross can be formed in one of three ways: through simple slits in the dough, with strips of pastry, or with pipes rolled up from a flour and water paste. This is applied before baking. In North America, the cross is sometimes made out of icing applied after baking.

After baking, the buns are then glazed on top.

Hot Cross Buns Sales

All supermarkets in the UK, as well as Marks and Spencers, make their own brands; you can even buy low-fat ones now. 28% of the Hot Cross Buns in England are sold by Marks & Spencer. The buns are made for them by Gunstones Bakery in Sheffield.

You can buy them year-round in the UK, though the big sales season is January through to Easter when 8 million packages (2011 figures) will be sold; 1.5 million of those packages are sold in the week before Easter.

Cooking Tips

Hot Cross Buns are actually quite dry on their own; they are best split in half horizontally, toasted and buttered.

The ones with an icing cross can be more problematic to toast.

History Notes

Some say the Babylonians made Hot Cross Buns and offered them to Ishtar, the Queen of Heaven, on the exact same day we now celebrate as Good Friday (making it a good thing that the Babylonians were good at calendaring, because tracking when Good Friday occurs is no mean feat even today.)

Many others believe that Hot Cross Buns are related to buns made by the Saxons for their “Eostre celebrations” — celebrations in honour of their goddess of spring, and that the cross actually represents the horns of the ox that was slain for the celebration (it’s difficult to know, though, why you’d feed an ox all winter and then slay it right at the start of ploughing season.) But if this is so, it wasn’t anything particularly out of the ordinary: it would have been bannock, such as the Celts throughout Britain made bannock for all religious celebrations, and not risen with yeast.

Others say the round bun represents a female, and the cross dividing it into 4 represents a phallus, making it a Celtic male and female union symbol.

Others try to tie them back to cakes made in ancient Greece for goddesses such as Artemis and Hecate, with the cross representing horns, as well as the 4 phases of the moon — New moon, 1st Quarter (sic), Full, and Last or Third Quarter (sic). Buns with two crossed lines called “quadra” were found in Herculaneum (reputedly.) But then, 31 buns with 4 crossed lines, making 8 triangles, were also found in the Bakery of Modestus at Pompeii, and there is little reason to think that the main purpose of any such lines was other than to make easy to tear off portions of bread. Even today, it is common to split a round loaf of bread with an “x” on top to allow better rising, with the decorative feature as a side benefit.

Others are itching to say the Aztecs made them, too, but that seems to be one mental leap too far, even for them.

In 1592, the sale of Hot Cross Buns in London was caught up in general regulations for all spiced fruit breads, buns, loaves and cakes:

“Item, That no Bakers, or other Person or Persons, shall at any time, or times hereafter, make, utter or sell by Retail, within or without their Houses, unto any the Queen’s Subjects, any Spice Cakes, Buns, Bisket, or other Spice Bread, (being Bread out of Size, and not by Law allowed) except it be at Burials, or upon the Friday before Easter, or at Christmas; upon pain of Forfeiture of all such Spice Bread to the Poor..” [1]Stow’s Survey of London, 1598. Law passed by Privy Council Lords for Elizabeth I, 1592. Recorded by J. Powel, Clerk of the Market for James I, in Book of Assize.

Enforcement of the spiced breads and buns restrictions proved difficult, and the regulation was discarded sometime during the time of James 1 (1603 – 1625.)

The cross seems to have been definitely on them by 1733: “Good Friday comes this month, the old woman runs, with one or two a penny hot cross buns.” [Poor Robin’s Almanack ,1733.]

Some say the cross was even present pre-reformation (mid 1500s), but they base that on the “fact” that Catholics revere the cross “above all other Christians.”

A bylaw in London in the early 1500s ruled that Cross Buns could only be sold on Christmas, Good Friday, or for funerals.

The place to buy them in London in the 1700s and first half of the 1800s were the two Chelsea Bun houses in London (see the entry on Chelsea buns.) They were sold on square black tins, as they were originally one large bread.

As yet, too, the name’ of such buns was just cross buns: James Boswell recorded in his Life of Johnson (1791): 9 Apr. An. 1773 Being Good Friday I breakfasted with him and cross-buns.’

The “hot” prefix started becoming more prevalent sometime in the early 1800s.

Literature & Lore

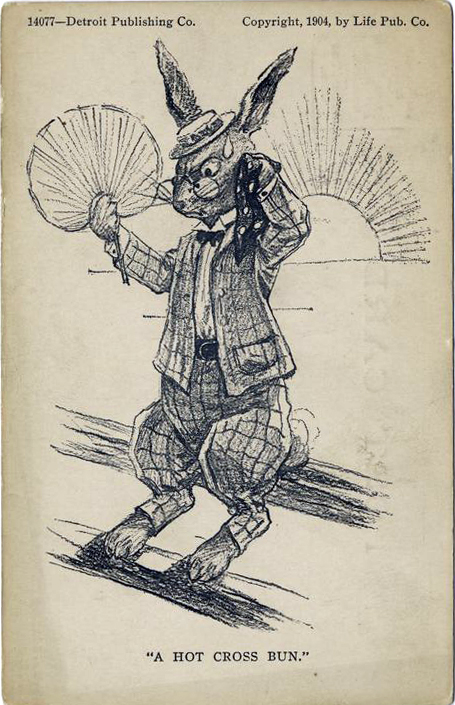

Hot cross bunny. © Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Photography Collection, The New York Public Library. “A Hot Cross Bun, Life Cartoons” The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1898 – 1931.

One superstition was that Hot Cross Buns actually baked on Good Friday will get through the coming year without growing mouldy (and once they’ve done that, they probably have a good chance of getting through eternity uneaten, as well.) Another superstition held that one should be put aside anyway for the coming year: if anyone fell ill during the year, a small piece of it would help the invalid recover.

One superstition is centred at the The Widows’ Son (aka The Bun House) at 75 Devons Road in London’s east end, just across from Devon’s Road tube station. According to local tradition, a widow lived on the site in 1824 (before the hotel was built.) The widow was expecting her son, a sailor, back for Easter from his first sea voyage. She put a Hot Cross Bun out for him on that Good Friday. She left it out for him when he didn’t return, and kept on adding another one each successive year till she died. The buns were found hanging from a beam in her house. A pub / hotel was built on the site in 1848. Owners of the hotel have kept the tradition going, getting a sailor each year to add to the collection. The buns hang in a net above the bar. True to another tradition, the buns haven’t gone mouldy. But those traditions apart, the pub interior today has kept up with the times and is actually quite modern.

Others say sharing a Hot Cross Bun with someone ensured unbroken friendship for the coming year. You’re supposed to say these words: “Half for you and half for me, Between us two shall goodwill be.”

If taken on a sea voyage, Hot Cross Buns would protect against shipwreck. Hung in the kitchen, they would protect against fire and help all bread to come out perfect. You’d replace last year’s with a fresh one from this year.

Some say you should kiss Hot Cross Buns before eating them (because of the cross on them.)

“Hot Cross Buns! Hot Cross Buns!

One a penny, two a penny, Hot Cross Buns!

If you have no daughters give them to your sons,

One a penny, two a penny Hot Cross Buns.”

“Hot cross buns, those pagan cakes originated in the pre-Christian era, are again in the bakery windows exhibiting their sugary charms. But less sugary than prewar; some are less fruity, some have lost their frosted cross. This blessing of the bakery, as we know it today, first rose in England. There the hot cross buns has flourished as in no other land. As far back as 1252 the bakeries were competing with the church in selling buns stamped with the cross — an illegal practice, but they did it just the same.” — Paddleford, Clementine (1898 – 1967). Food Flashes Column. Gourmet Magazine. April 1946.

Sources

[1] Stow’s Survey of London, 1598. Law passed by Privy Council Lords for Elizabeth I, 1592. Recorded by J. Powel, Clerk of the Market for James I, in Book of Assize.

Clay, Xanthe. Hot cross buns: Warm, soft and best with butter: Tips and tricks from the nation’s favourite hot cross bun maker. London: Daily Telegraph. 16 April 2011.

Fabricant, Florence. Hot-Cross Buns: Giving Tradition A Fresh Accent. New York Times. 20 March 1991.

Hot cross buns

© alisonyo / pixabay.com / 2016 / CC0 1.0

References

| ↑1 | Stow’s Survey of London, 1598. Law passed by Privy Council Lords for Elizabeth I, 1592. Recorded by J. Powel, Clerk of the Market for James I, in Book of Assize. |

|---|