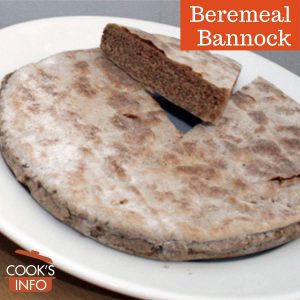

Bannock. Breville USA / flickr.com / 2013 / CC BY 2.0

Bannock is a quick, flat bread.

The most authentic version is a round or oval piece of unleavened dough, cooked on a griddle or girdle. The middle will rise or puff a bit.

There are many, many different recipes. They vary by flour or meal used, by whether leavened or unleavened, by special ingredients added, by method of cooking, and by any festival or ritual that the bannock is meant for.

When a bannock is cut up into four quarters, each quarter is called a “farl.”

The word “bannock” is often applied to any sort of grain or meal based baked item that is round, and largish. Closely related items in English-speaking countries are Damper in Australia, Damper Dogs and Toutons in Newfoundland.

- 1 Leaveners used

- 2 Flour

- 3 Fat

- 4 Other ingredients

- 5 Cooking methods

- 6 Bannock in North America

- 7 Scottish versions

- 8 Literature & lore

- 9 Language notes

-

10

Types of bannock

- 10.1 Béaltaine Bannock

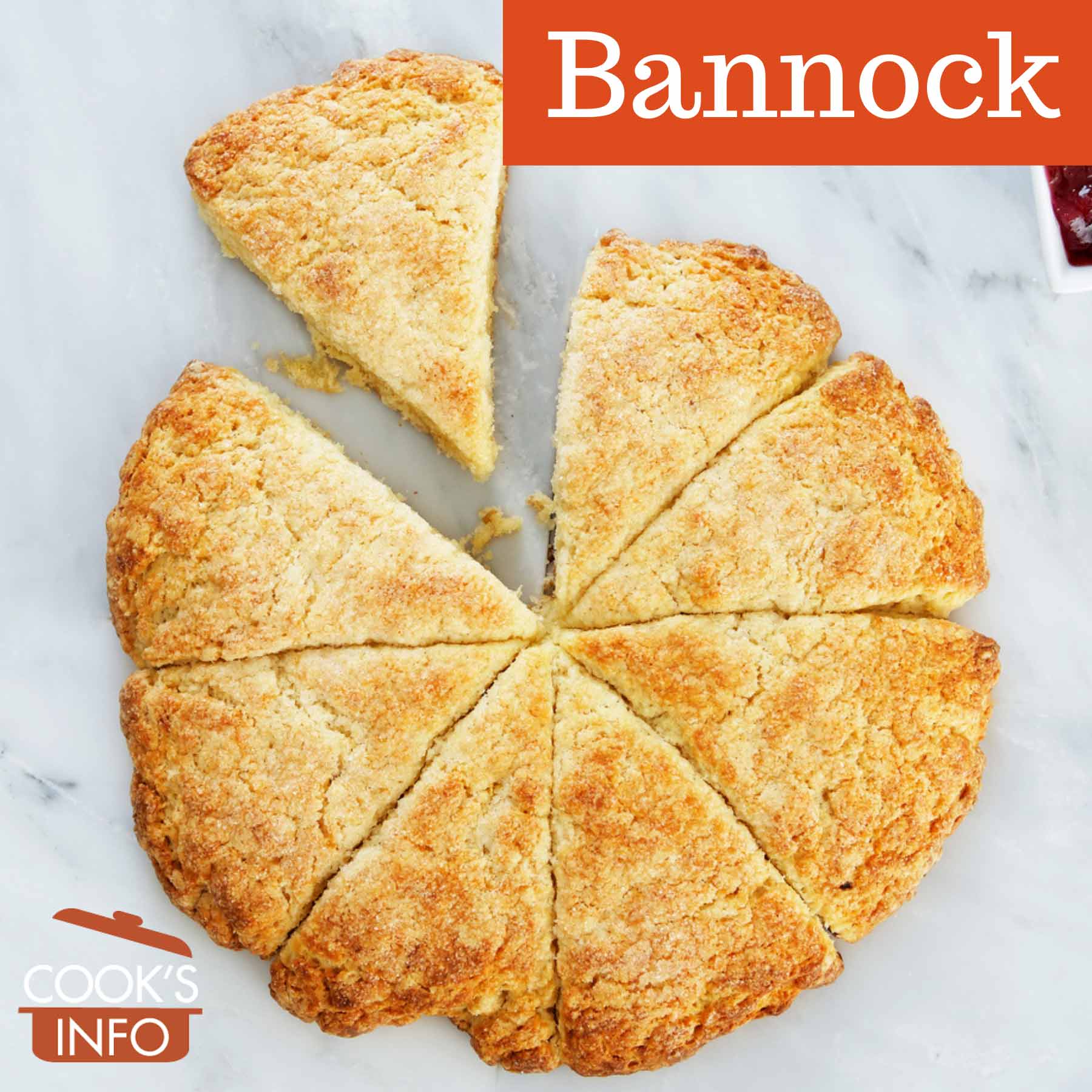

- 10.2 Beremeal Bannock

- 10.3 Bride's Bannock

- 10.4 Cod Liver Bannock

- 10.5 Cryin' Bannock

- 10.6 Fallaid Bannock

- 10.7 Fife Bannock

- 10.8 Hogmanay Bannock

- 10.9 Lammas Bannock

- 10.10 Marymas Bannock

- 10.11 Mashlum Bannock

- 10.12 Michaelmas Bannock

- 10.13 Pease Bannock

- 10.14 Pitcaithly Bannock

- 10.15 Salt Bannock

- 10.16 Samhain Bannock

- 10.17 Sautie Bannock

- 10.18 Selkirk Bannock

- 10.19 Silverweed Bannock

- 10.20 St Bride's Bannock

- 10.21 St Columba's Bannock

- 10.22 Teethin' Bannock

- 10.23 Yetholm Bannock

- 10.24 Yule Bannock

Leaveners used

Some bannocks come out quite heavy, and are meant to.

Historically, bannock were more likely to be made without any leavener.

Yeast-risen ones would also have been made, by saving starter dough from the last batch to make the next batch with. Selkirk bannock is an example of a yeast-risen bannock.

In the early 1800s, baking soda came on the market commercially, and started to be used in some bannock recipes along with an acidic ingredient for it to react with, such as clabbered milk or buttermilk. Then in the mid 1800s, baking powder came along which didn’t require the added acid.

Bannock leavened with a chemical leavener, such as baking soda or baking powder, can be similar to baking powder biscuits or scones, except the dough is pan cooked rather than baked in an oven.

Flour

Some bannock recipes use just flour, some add rolled oats. The flour could have been wheat flour, if available and affordable to you, or barley meal. As bannock originated in Scotland, the flour would have originally been barley meal, because in Scotland, barley preceded both oats and wheat. The poor kept on eating barley long after the affluent middle-classes had forgotten it existed. Bannock could also be made from “pease meal”, which is ground field peas. Wheat flour, however, bound ingredients together the best, so it was always popular when it was available. In the West of Scotland, bannock is still more likely to be made with oats, and exclusively with oats — in fact so much so that the distinction between bannock and oatcakes can blur.

Fat

Some bannock recipes (particularly perhaps Canadian ones) use bacon fat instead of butter, dripping or lard. Some bannock would be fried up in any kind of fat available, depending on the location and geography, from beef dripping to pork lard to moose fat.

Other ingredients

Some bannock versions use water as the liquid, some use milk.

A basic bannock doesn’t have much flavour to it. It will take on flavour from the kinds of flour used, special ingredients added, and any fat it is fried in.

Bannock can have dried fruit or peel mixed in to become a treat with tea.

Cooking methods

Generally, you form bannock dough into balls, and press with your hands until flat. Bannock can be cooked as one large piece that you break up, or as several small cakes.

Scots cooked bannock on a griddle called a “bannock stone” (“clach bhannag” in Scottish.) It was a flattened, D-shaped piece of sandstone used as a griddle. It would be put on the floor in front of a fire where it could heat up. Some people bake bannock in ovens now, though home ovens of course weren’t really widespread until the late 1800s.

Bannock dough can also be put as balls into stew and served as dumplings

Bannock in North America

Bannock was brought over by Scottish explorers, traders and settlers. In Canada, traders for the Hudson’s Bay and Northwest companies, many of whom were Scottish, set up a network of permanent trading posts and sold flour at them, for which natives could trade. They probably introduced bannock to native North Americans. Now, bannock is not particularly well known in Canada outside of some native communities, grade school history books, and food historians.

At some folksy tourist shops in Canada, you can buy “bannock mix.” There is usually at least one obligatory bannock recipe in every Canadian cookbook. Many Canadians are unaware of bannock’s Scottish origins.

In the United States, bannock tended to be made more by Indians, and known by white people as “Indian bread.” The grain used was often cornmeal. Some Indians will deep fry it, making it very close to fry bread.

Different First Nations in North America have evolved regional versions for which they are known. The Chippewa have two versions which both use baking powder, a fat such as lard and a dried fruit. One of the versions uses wheat flour and is often unsweetened; another uses cornmeal, and a sweetener such as honey or maple. Both versions are fried up in a small amount of oil.

North American versions put most emphasis on cooking bannock using campfires. They can be cooked in cast iron frying pans, on top of a heated rock, or wrapped around a stick, preferably a green wood one that won’t burn.

Scottish versions

Yetholm and Pitcaithly bannock are actually what we would call shortbread.

Four main variations of bannock were historically tied to the druidic divisions of the year into four main parts:

- St Bride’s Bannock for 1st February (spring), Imbolg;

- Béaltaine bannock for 1 May rituals;

- Lammas bannock for harvest festivals 1 August, Lughnasadh;

- Samhain Bannock for the start of winter rituals at the end of October.

Literature & lore

In 19th Century USA cookbooks, cornmeal bannock is common.

“Bannock Cake. 1 ½ pint of Indian meal, scalded; four eggs, well beaten; one quart of milk, warmed, with two tablespoonfuls of butter stirred in; salt to your taste; bake in a square or round tin pan, and cut it up in slices. The lightness of this depends on the beating.” — From “Mrs. Goodfellow’s Cookery As It Should Be,” 1865.

“Indian cake, or bannock, is sweet and cheap food. One quart of sifted meal, two great spoonfuls of molasses, two teaspoonfuls of salt, a bit of shortening half as big as hen’s egg, stirred together; make it pretty moist with scalding water, put it in a well-greased pan, smooth over the surface with a spoon, and bake it brown on both sides, before a quick fire. A little stewed pumpkin, scalded with the meal, improves the cake. Bannock split and dipped in butter makes a very nice toast.” — Lydia Maria Francis Child. The American Frugal Housewife. 1833.

“Sift a quart of fine Indian meal, mix it with a salt-spoonful of salt, two large spoonfuls of butter and a gill of molasses; make it into a common dough with scalding water, or hot sweet milk, mixing it well with a spoon; put it in a well-buttered skillet, make it smooth, and bake it rather briskly. When it is done, cut it in thin smooth slices, toast them lightly, butter them, stack them, and eat them warm.” — Lettice Bryan. The Kentucky Housewife. 1839.

Language notes

Bannock comes from the Gaelic word spelled variously as “bannach” or “bonnach”, which meant “morsel.” Some attribute the Gaelic word to the Latin word “panicum”, thinking it meant bread, but it actually meant “panic grass”. An alternative Latin word for bread, “panicus”, wasn’t invented until the 1500s, so it’s very unlikely that “bannach” was influenced in fact by a Latin word.

In the 1500s, the plural was spelled “bonnokkis” or “bannokis.”