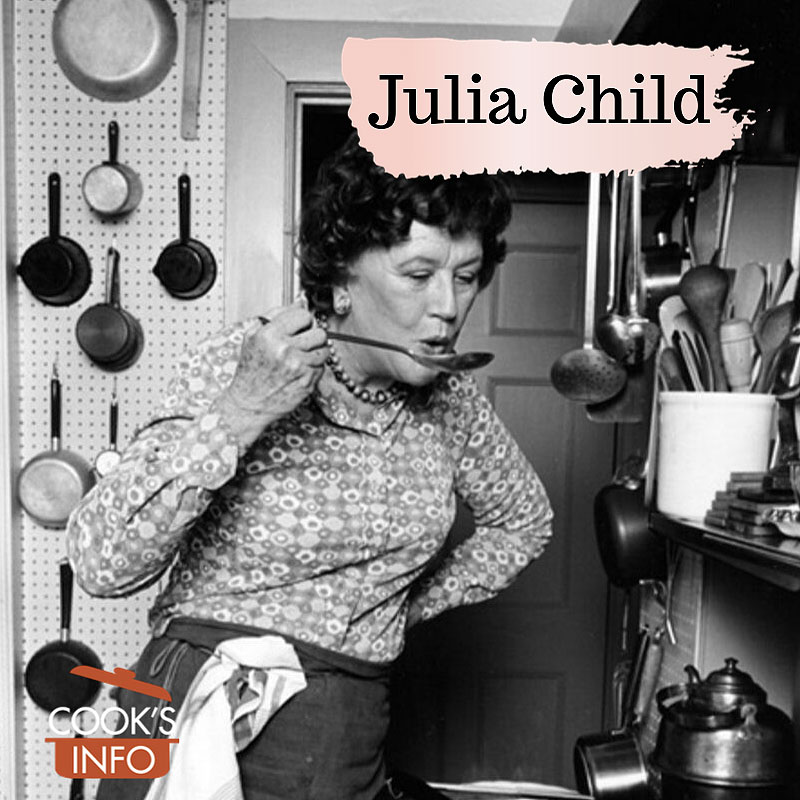

Julia Child in her kitchen as photographed by ©Lynn Gilbert, 1978, Cambridge, Mass. Lynn Gilbert / Wikimedia / 1978 / CC BY-SA 4.0

Julia Child was the person who more than anyone else brought French cooking to North American middle-class households as a TV personality and author. She is only familiar to North Americans, though; she remains mostly unknown in Britain and in Europe.

- 1 Life and Times

- 2 Chronology of her life

- 3 Books by Julia Child

- 4 Julia Child’s “The French Chef” TV series

- 5 The French Chef and Europe

- 6 Have Julia Child’s recipes aged well?

- 7 The Julia Child dropped turkey / chicken myth

- 8 The film Julie & Julia

- 9 Julia Child’s blowtorch

- 10 Julia Child and the LGBT community

- 11 Literature & Lore

- 12 Videos

- 13 Sources

Life and Times

Julia was very tall — six feet two inches (188 cm). She described herself as a “natural ham” with her breezy approach on her TV shows. She was always very definite, though, that she was not a TV entertainer, but rather an educator on TV. She presented cooking as fun for the viewers — she didn’t seem too concerned about being messy in her cooking — but actually felt that cooking was a discipline.

Julia wasn’t keen on Italian and Mexican food. Italian food lacked the sort of technique that interested her about French food, and she found Mexican food too spicy (until her final days in Montecito, California.) She also didn’t like grilled vegetables. She wasn’t a food snob, though: she liked beer, and would buy Wonder Bread and iceberg lettuce and hamburgers. And, she was open to modern gadgets: she popularized the food processor, and the blowtorch and was amongst the first to have a bottom-freezer fridge in North America. Still, to the end, she disapproved of bottled salad dressings.

A friend of Canadian-born John Kenneth Galbraith (economist, 1908 – 2006), Julia was also, like Galbraith, a Democrat. But she was no populist. She berated the “Food Network”, saying that the attention span of the audience they attracted was too short, wanting entertainment rather than education. She referred to “very popular shows on the Food Network which your gas station attendants will look at…..” She said that public television (PBS in America) was the “many paying for the few, but we need that for the few people who are serious about what they are doing… specialized group of people who want to be educated or enlightened in special things.” On the other hand, while she praised public television for showing teaching programmes (such as hers) that commercial TV wouldn’t, because commercial TV had to make money, she certainly liked to make money herself and ended up a very rich woman. She said of public television, “PBS never pays much of anything.” Some say that she was somewhat elitist, with her disdain for Italian food, and her emphasis on training and serious study. Others argue that she patently wasn’t, because she sought to bring French cooking to ordinary (upper middle-class) American kitchens.

Julia would say of the British class system, “We’re lucky in this country, we don’t have that”, but she was pretty high up on the class scale in her own country. She and her husband had a second home, a house they built in Provence, France, and she pronounced “tomatoes” the British way. And she was conservative in some ways, extolling long hours in the kitchen at a time when working-class women were just trying to break free of it. She felt that good cooking had to come out of tradition, and by tradition, she meant French tradition, and women in the kitchen.

When Julia died, she had been working on her memoirs with her grand-nephew, Alex Prud’homme, but only had two chapters completed. She asked for no funeral, but a private memorial service was held. Her papers are at The Schlesinger Library of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Her own home kitchen, complete right down to the utensils, was donated in 2002 to the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, where it became a permanent exhibit. [1] Julia’s pots and pans originally went to COPIA, the American Center for Wine, Food & the Arts, in Napa, California. When the center went bankrupt in December 2008, the Child family transferred them to the Smithsonian to re-unite them with the rest of the kitchen. Py-Lieberman, Beth. Julia Child’s Pots and Pans Are Back in Her Kitchen. Smithsonian Magazine. 29 July 2009.

Julia Child’s kitchen at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. Matthew Bisanz / Wikimedia / 2009 / CC BY-SA 3.0

The first truly fancy French restaurant she dined at was during the years she and her husband lived in Paris, a restaurant called “Le Grand Vefour” on the northern side of the Palais Royal, when Raymond Olivier was the chef.

She was a heavy smoker, even between courses, not quitting until a medical scare in 1968. [2]Stewart, David. Empowered to cook: Julia gives us the courage, shows us her joy. Takoma Park, Maryland: Current. 8 June 1998. Before that, Julia Child had a list of items she wanted to take to the studio for every episode of the French Chef being shot: on the list were additional clean blouses, and a “zipper bag with cigarettes in it.” [3]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Duke University Press. 2011. Kindle Edition. Page 139.

See also: The French Chef Debuts Day (11th February)

Chronology of her life

- 1912 — Julia Child was born Julia Carolyn McWilliams on 15 August 1912 in Pasadena, California. Her father, John McWilliams (1880 – 1962), was a 1901 Princeton graduate from Chicago who became a “farm consultant,” and then became wealthy through investments that had paid off for him. He would later help finance Richard Nixon’s first political campaign. Her mother was a red-head, née Carolyn Weston (1877 – 1937, nickname “Caro”), who didn’t have to work, and didn’t cook much. From “old Massachusetts money”, she grew up in a house that had servants, nurses, a governess, a coachman, and cooks. Nevertheless, Caro was the first woman in Dalton County, Massachusetts to get a driver’s licence. John and Caro had met at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1903, married on 21 January 1911, and moved out to Pasadena, California, where John’s family was originally from. They set up house with a cook and a maid. Julia was the eldest of three children. Her brother’s name was Byron Weston McWilliams; her sister, named Dorothy. She went first to a girl’s boarding school, the Katherine Branson School in Ross, Marin County, California. Her family was untouched by the Great Depression. She described her family as a “moderate income” family, but she was from a class of women who were expected to enter into the “leisure class”, unlike working class women.

- 1934 — Julia graduated from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts with a degree in history. It was an exclusive women-only college. Her mother had graduated from Smith College in 1900. Julia stayed home for about a year after college, then took a PR job for a New York furniture store chain W. & J. Sloane writing copy for its advertising and promotion department for $18 a week. She shared an apartment with two other girls that cost them $80 a month, and bought three course lunches for 50 cents. Julia returned to Pasadena when her mother died of high-blood pressure, and did some PR work there (a job from which she was eventually fired for not doing as she was told.)

- 1941 — Her father established the Carolyn Weston McWilliams Scholarship Fund at Smith College

- 1942 — By now the United States had joined the rest of the allies in the Second World War. Julia knew how to type, which landed her a job for the US Information Agency in Washington, then a job transfer to the Office of Strategic Services (now the CIA.) During the war, she continued working for them, and was posted in their offices in Kandy, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), as a filing clerk. She travelled there by way of Bombay, then by train across India to Madras, then onto Ceylon.

- 1943 — While Julia was in Ceylon, she met Paul Cushing Child (born in New Jersey, grew up in Maine; 15 Jan 1902 – 12 May 1994), head of the “chart-making” division there. Originally from Maine, he was a Francophile who appreciated good food. He spoke French fluently, and had taught at a boy’s boarding school in the Dordogne in France. He was also a passionate amateur photographer. Paul was 5 feet, 11 inches, and 10 years older than her. Julia said she started to get interested in food in Ceylon. At first the staff were fed native food, but when people started getting dysentery, the military took over catering them. Julia said that the military food was so bad, that everyone would sit around and talk about good food they remembered.

- 1945 — Julia and Paul both returned to America in 1945. She returned to Pasadena; he went to stay with his brother in Washington. The two kept in touch, and did a visit together to his family in Maine. In the same year, Julia followed up her new interest in food with some cooking studies at the Hillcliffe School of Cookery in Beverly Hills.

- 1946 — Julia and Paul got married in September in Lumberville, Pennsylvania, after a road trip from California to Washington. They spent a year in Washington. (The couple had no children.) She changed her name when she got married to Julia McWilliams Child, but never used the McWilliams part professionally.

- 1948 — Paul Child was posted to Paris as part of the US Information Service, attached to the American Embassy on a salary of US $6,000 a year. Paul hadn’t been in France since 1933, so he was happy to get back. Julia was 37 at the time; Paul 46. They would be in Europe for almost six years. They landed at Le Havre in November 1948; they’d brought their own car — a Buick station wagon — over to Europe with them on the liner “America.” They got in it and drove it on to Rouen. There, she had her first meal in France, at a restaurant called “La Couronne” (Paul had known the restaurant from his previous time in France.) She had “oysters portugaises”, and either duck or sole meunière. [4]Paul wrote a letter that very first day to his brother; in it, he said they had “filet de sole.” Julia’s memory of what it was exactly at the first meal varied over the years. In “My Life in France” (p. 18) and in the fish chapter of “From Julia Child’s Kitchen,” she says “sole meunière.” In the piece she contributed to the 1988 book “Christmas Memories With Recipes” [Waxman, Maron L. Christmas Memories With Recipes. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 1988.], and again in 2000 in Gourmet Magazine, she said it was duck. [per Laura Shapiro, Julia Child: A Life. New York: Penguin. 2009. P. 28-29] She was hooked on French food (both duck and oysters remained two of her very favourite foods for the rest of her life.) She was also gripped by the techniques and methods she saw them using; she said that “ladies magazine” recipes had never “turned her on.” While in Paris, they lived in an apartment owned by a Madame Perrier, on the top floor of a house right off Place de la Concorde. Julia enrolled in a class of ten to twelve people at the Cordon Bleu cooking school from October 1949 to April 1950. Her mentor there was chef Max Bugnard, who had worked with Escoffier at one point. Her classmates were US servicemen, paid for by the military. Through a friend, she met a woman named Simone Beck, who invited her to join a club, “Cercle des Gourmettes” (the female gourmets’ circle.) Julia also enrolled in the Berlitz language school to learn French for two hours a day. Julia and Paul budgeted their money out, and allowed themselves $2.00 each per week for “mad money.”

- 1950 — Julia graduated from Cordon Bleu.

- 1951 — Julia, along with Simone Beck and a third woman, Louisette Bertholle, started a cooking school in Paris that they called “l’École des Trois Gourmandes” (the school of the three gourmets) to teach cooking to Americans in Paris who didn’t have enough French for Cordon Bleu. They taught in their apartments, but didn’t make any money on it. She said they’d buy the ingredients for the classes, but then people would often cancel, causing them to lose money. At the time, Simone was already working on a book with Louisette. The two already had a third person as a collaborator, but he died and Julia was invited to take his place. A publisher had already agreed to take on the book, but Julia managed via a friend to get a small trial excerpt of it (on soups and sauces) into the hands of Houghton Mifflin publishers, who said they wanted it. In the end, though, Houghton Mifflin changed its mind: they said no one in America would ever want to do that kind of cooking. The book went to Alfred A. Knopf, who published it as “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” The book started off as Simone’s child, but by the time the book moved to American publication with Knopf, Julia had taken the lead and become the star. After Paris, Julia and Paul lived briefly in Marseilles, until about 1954, then German, and finally in Norway.

- 1956 — Julia and Paul returned to America and moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts. She would live in the same house there at 103 Irving Street until 2001.

- 1961 — Julia and Paul build a vacation house in Plascassier in the south of France, near the vacation property there owned by her friend Simone Beck. They would keep it until 1992, travelling there every winter.

- 1963 — Julia is 51. Her programme, the French Chef, debuts on 11 February 1963 on WGBH-TV out of Boston, Massachusetts. (See below for more details.)

- 1964 — Award: Julia won a George Foster Peabody Award for “The French Chef” (this was in 1964, not 1965, as was reported in the press at the time of her death.)

- 1965 — Award: Julia won an Emmy for “The French Chef.”

- 1966 — Julia was featured on cover of Time Magazine on 25 November 1966.

Julia Child on the French Chef. AustinMini 1275 / flickr / 2016 / Public Domain

- 1966 — The French chef went off the air for 4 years.

- 1967 — Award: Julia was awarded the “Ordre de Mérite Agricole” by France.

- 1968 — Had a mastectomy.

- 1970 — Julia publishes Volume Two of “Mastering the Art of French Cooking.” She wanted (based on a suggestion from a Judith Jones) to have a recipe for a classic French baguette. She assigned the task of experimenting to her husband Paul, who made an estimated 60 loaves before giving up. He pointed Julia, however to Raymond Calvel, a bread expert in France, and based on assistance from Calvel, Julia developed an eleven-page recipe that would work in North America for a classic French baguette. While stories of her collaboration with Calvel are known in the food world in North America, biographies of Calvel do not mention Child at all.

- 1970 — The French Chef TV programme starts up again, this time in colour. It ran for only one year until it was cancelled.

- 1972 — Award Nomination: Julia was nominated for, but didn’t receive, an Emmy for The French Chef.

- 1972 — Rebroadcasts of The French Chef introduce home television captioning for the first time, ever. [5]”The nation’s first captioning agency, the Caption Center, was founded in 1972 at the Boston public television station WGBH. The station introduced open television captioning to rebroadcasts of The French Chef with Julia Child… Captions on The French Chef were viewable to everyone who watched, which was great for members of the deaf and hard of hearing community, but somewhat distracting for other viewers. So the Caption Center and its partners began developing technology that would display captions only for viewers with a certain device.” — Allen, Scott. A Brief History of Closed Captioning. Mental Floss. 16 March 2015. Accessed June 2021 at https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/22685/brief-history-closed-captioning

- 1976 — Award: Julia was awarded the “Ordre de Mérite National” by France.

- 1981 — Julia co-founded the “American Institute of Wine and Food” (San Francisco), along with Robert Mondavi and Richard Graff (1937–1998).

- 1983 — Julia did a TV programme called “Dinner at Julia’s.”

- 1986 — Julia co-founded the James Beard Foundation (New York.)

- 1993 — Julia did a TV programme called “Cooking With Master Chefs.”

- 1994 — Award Nomination: Julia was nominated for, but didn’t receive, an Emmy for “Cooking With Master Chefs.”

- 1994 — Julia did a TV Special for PBS called “Julia Child & Jacques Pepin: Cooking in Concert.”

- 1994 — Julia’s husband, Paul, died.

- 1994 — Julia gave money for a $200,000 trust fund at Smith College.

- 1995 — She did a TV programme called “In Julia’s Kitchen with Master Chefs.”

- 1996 — Julia did a TV Special called “More Cooking in Concert.”

- 1996 — She did a TV programme called “Baking with Julia.” It ran for 39 episodes; during them, she had 26 bakers on the show.

- 1997 — For her 85th birthday, Julia got a private tour of the White House. While in Washington, she got to have lunch with Katharine Graham (1916 – 2001), owner of the Washington Post.

- 1999 — Julia did a TV series for one year called “Julia Child and Jacques Pepin Cooking at Home.”

- 2000 — Award: Julia was awarded the “Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur” by France.

- 2001 — Julia moved from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Montecito, California (90 miles / 145 km northwest of Los Angeles.) She donated the 103 Irving Street house in Cambridge to Smith College, which then sold it off. In Montecito, she lived in a garden apartment in an assisted-living retirement community. The apartment had a patio and a small kitchen which she called “small but efficient.” When asked if she would miss New England, she said, “I always remained a Californian. I never really became a New Englander. People ask, ‘Aren’t you going to miss the change of seasons?’ and I say no. I like it just like this every day.” In Montecito, her favourite restaurant was a Mexican place called “La Super-Rica” which she pronounced simple but as authentic as you could get north of the border. She said, though, that you couldn’t get a decent breakfast anywhere in the area outside her retirement complex, where breakfasts were good because they served lots of bacon. For company, she had a cat named “Minou.” [6]Wilson, Craig. Celebs savor Montecito’s exorbitant vistas. USA Today. 30 January 2002.

- 2002 — She had knee-replacement surgery.

- 2003 — Award. Julia was awarded the American Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Bush.

- 2004 — Julia Child died in her sleep on Friday, 12 August 2004, aged 91, just 2 days before her 92nd birthday, of kidney failure.

Books by Julia Child

- 1961. Mastering the Art of French Cooking (with Simone Beck and Louisette Bertholle. Nine years in the writing.)

- 1968. The French Chef Cookbook

- 1970. Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Vol. II (with Simone Beck)

- 1975. From Julia Child’s Kitchen

- 1978. Julia Child & Company

- 1979. Julia Child & More Company

- 1989. The Way to Cook (published in October)

- 1993. Cooking at Home with Master Chefs

- 1999. Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home

Julia Child’s “The French Chef” TV series

Julia started her TV programme, “The French Chef”, at the age of 51, produced by WGBH-TV out of Boston, Massachusetts. The programme ran for 119 episodes until 1966, and then again for three years from 1970 to 1973.

The television show came about while she was promoting her book, “Mastering the Art of French Cooking“. In February 1962, she had landed a few minutes on a live WGBH TV programme to talk about the book, and as part of her time on air, she whipped up an omelette.

“The show was called I’ve Been Reading, and it was hosted by Professor Albert Duhamel on WGBH, channel 2, the local public television station. Instead of the usual five-minute spot, we were given a full half-hour. I didn’t know what we would talk about for that long, so I arrived with plenty of equipment. They had no demonstration kitchen, and were a little surprised when I pulled out a (proper) hot plate, copper bowl, whip, apron, mushrooms, and a dozen eggs… I demonstrated the proper technique for cutting and chopping, how to ‘turn’ a mushroom cap, beat egg whites, and make an omelette.” [7]Child, Julia with Alex Prud’homme. My Life in France. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. Page 236.

Both the producers and viewers were taken by her cooking style on TV. “Twenty-seven viewers wrote to the station, wanting to see more.” [8]Mellowes, Marilyn. Julia! America’s Favorite Chef -Biography of Julia Child. PBS.org. 15 June 2005. Accessed July 2019 at http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/julia-child-about-julia-child/555/

As a trial balloon, the station commissioned three pilot cooking episodes with her .

“Encouraged by the response to our little cooking demonstration on I’ve been reading, the honchos at WGBH asked me and the show’s director, 28-year-old Russell Morash, to put together 3 ½ hour pilot programs on cooking. The station had never done anything like this before. But if they were willing to give it a whirl, then so was I.” [9]My Life in France. Page 238.

For the first pilot, she made soufflé, for the second an omelet, and for the last of the three trial episodes, she made coq au vin: “Child decided to center the pilots on decidedly classic bourgeois French fare — soufflé, omelet, and coq au vin — and all three were shot in one week in June 1962.” [10]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 129.

“During the summer of 1962, she taped three pilot programs — omelets, coq au vin, and souffles.” [11] Shapiro, page 100.

The pilots were to have been taped in the WGBH studio, but a fire just before taping rendered that impossible. The Boston Gas Company lent them some kitchen studio space instead.

Julia wrote years later:

“On the morning of June 18, 1962, Paul and I packed a station wagon with the kitchen equipment and drove to the Boston Gas Company in downtown Boston. Our first show would be called ‘the French omelette’… The second and third shows, ‘coq au vin’ and ‘soufflés’, were both taped on June 25, to save money… Once we had finished taping, our technicians descended on the coq au vin like starving vultures.” [12]My Life in France. Pp 240-242.

The three pilot programs were lost, likely taped over. [13]”Those pilot programs have been lost.” Shapiro, page 100.

The first pilot, on omelets, aired on 26 July 1962. [14]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 129.

Based on the success of the pilots, the station then commissioned a 26-episode series. Taping for it (in black-and-white) began in January 1963.

“WGBH boldly suggested that we try a series of twenty-six cooking programs. We were to start taping in January, and the first show would air in February 1963. And with that, The French Chef, which followed the ideas we’d laid out in Mastering the Art of French Cooking, was under way.” [15]My Life in France. Page 243.

The producer would be a Russ Morash. The Boston Gas Company had dismantled its kitchen studio, so production moved to kitchen studios at the Cambridge Gas and Electric Company and stayed there for the next several years.

For the very first show, she made boeuf bourguignon. It was broadcast on 11 February 1963.

Sadly, the first thirteen episodes have been lost to us. They were taped on old, used tape, which later just degraded away with time. [16]”NET’s distribution of The French Chef began in the fall of 1964 with thirteen programs, numbered 14–26 (the original episode 13 had not been saved).” — Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 208.

Rather than mourning their loss, Julia Child actually said she was glad:

“…the first thirteen shows no longer exist. When we started, “The French Chef” was a purely local New England program, and before WGBH-TV realized duplicates were needed to serve other educational stations throughout the country the first thirteen tapes had worn out, and I am glad of it. Although they did possess some of the unpredictable quality of a contemporary happening, their demise allowed us to do over all but one of those recipes later on when we were more expert.” [17] Julia Child, 1998 introduction to The French Chef cookbook. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. [Re-issue, hardback edition.]

In any event, the programme was picked up by a station in Pittsburgh, then San Francisco, then New York. She was paid $50 an episode, plus a budget for ingredients. Paul helped her with the prep for the shows.

At the time, many of her TV crew had never eaten fresh asparagus or fresh artichokes, and you couldn’t buy leeks. She ended every episode sitting at a table, saying “Bon appetit.”

“On the spur of the moment, I had decided to end each show with the hearty salutation “Bon Appetit!” that waiters in France always use when serving your meal. It just seemed the natural thing to say, and our audience liked it.” [18]My Life in France. Page 246.

Julia was hitting the air waves just at the right time. The Kennedys in the White House, about whom everything was news, had a French chef. And, the age of transatlantic travel had just begun, when Americans could travel to France in a matter of hours by, rather than sailing days by liner.

This 1963 series is sometimes claimed by Americans to have been the first cooking programme ever on TV. It wasn’t, however: there was Lena Richards on WDSU TV in New Orleans from 1947 to 1949, as well as Philip Harben in Britain in 1946 and Fanny Craddock, for the BBC.

The first run of the programme would run until 1966, making a total of 119 episodes in black-and-white.

It’s interesting to note that The French Chef was not a PBS (Public Broadcasting Service ) show. It was a product of her local educational station in Boston, WGBH. The PBS network was not created until 1967 — a year after the first run of the French Chef ended. But a 1965 report calling for the creation of a public broadcasting service cited one example of an educational show that it hoped could represent the type of programming aimed for, and that was The French Chef.

The show was carried, though, in its second incarnation on the PBS network from 1970 to 1973 (discussed below).

A book named after the series was released in 1968, and would be re-issued many times over the years. In 2006 she wrote:

“I am delighted that we are reissuing the little book, which accompanied our first “The French Chef” television series. Program Number One aired here in Boston on February 11, 1963, in the days of black-and-white TV.” [19]Child, Julia. The French Chef Cookbook. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. [Re-issue, hardback edition.]

Any printed recipes that were sent out to viewers upon request had to acknowledge Knopf’s copyright on them. The recipes could only be given out on single pieces of paper, and not be stapled together or bound together in any way that implied a recipe booklet. They only had permission to give out single recipes to promote the actual book.

Legend has it that the crew used the lunch break to devour the culinary results of Child’s morning efforts, and the Child archives have a delightful cartoon that shows a bunch of chubby men walking past a visitor to WGBH who is being told by a tour guide that this is the crew of The French Chef. But Russ Morash claims that many members of the crew found what Child was making too exotic and strange and said they preferred to bring downscale grinder sandwiches almost as a reassertion of their working-class identity.

In fact, when the show moved from the Cambridge Gas and Electric Company back to the WGBH studio in 1965, it took on a group of (female) volunteers who helped with prep (cutting vegetables and so on) and cleanup. They, not the crew, were given the day’s cooking as a reward. Eventually, these volunteers came to matter very much to Child, and she trusted them to try out her upcoming recipes in their own homes to make sure her lessons could be reproduced by average cooks in a variety of kitchens.” [20]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 155.

In 1965, the production studio was moved back to a purpose-built kitchen studio at WGBH.

“In 1965 a kitchen set constructed for use within the new, post-fire WGBH building, and built especially for The French Chef, was finally ready, and Child’s series moved in there to remain through the color version of the show in the 1970s, when the set was overhauled to give it an even newer look. The WGBH set was massive (whereas Russell Morash estimates that the space Child worked in at Cambridge Gas and Electric probably was no deeper than eight feet from kitchen counter to back wall), yet it was not a fixed, permanent set. It was made instead to be dismantled and then stored after each day’s shooting so that the studio space could be used for other programs… Child seems to have loved the new set at WGBH when she moved onto it in 1965, and one can sense a new confidence and enthusiasm in her in the episodes from 1965 on…

The set, as Child explained in the promo for it, included working double ovens, a rotisserie, an extra large refrigerator and separate freezer, double sinks, a tap that produced immediate boiling water, a seven-burner stove, and a lot of counter space. The set was distinguished by a French country visual style created by WGBH’s set designer Francis Mahard (who later won an Emmy for the set design of Frontline), with chestnut paneling throughout (showing quaint scenes of French cookery) and carefully placed rustic items such as pitchers, decorative plates, earthenware jugs and jars (all of which Mahard had found in antique stores in Boston) on the back counters and hung up on the walls. To the left of the kitchen (from the viewer’s point of view), and acceded to by a door at the back of the set, was a dining-room set (at Boston Gas, the dining room had been to the right). Windows on the back wall opened onto what was supposed to be a garden, indicated by a solid background (blue in the color episodes) standing in for sky with tree branches, creating the impression of a pastoral locale (in the plans for one episode, Child was to throw scraps out the window as if feeding farm animals).

In passing, it is worth noting that the rolling, modular counters for the in-house set were soon lent to another WGBH cooking show, Joyce Chen Cooks. That program debuted in 1966…. [21]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 141.

The return to their own studio space at WGBH also allowed the studio to introduce live audiences. They charged $5 a person to come and watch Julia live.

“For each taping, 100–150 paying guests would come to one of the episodes being shot that day, at 4 P.M. or 8 P.M. Significantly, the later taping was termed an “evening performance,” as if to give it the patina of the special event, the culturally enriching evening out on the town. Admission was $5 (not a small amount at that time). Often, the audiences were composed of special groups. There were frequent visits by women’s clubs, and on one occasion students from the Harvard School of Business attended… After each shoot, Child would meet with the audience. As an internal memo explains, “For ten minutes—no more—Julia will answer questions and will then flee the audience so as not to get trapped.” [22]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 143.

The use of live audiences for The French Chef seems to have dropped away for a while after mid-1966 because a WGBH administrator, David Ives, felt that word might get out that Julia as filming on a television set, rather than in an actual home.

But Julia would often say she missed cooking with actual people in front of her, and the “the practice of taping in front of audiences returned and persisted into the 1970s.” [23]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 145. In its second incarnation from 1970 to 1973, the show had a live audience.

The first run wrapped up in 1968. It was not intentional:

“The original intent was to have episodes of the new French Chef appear in 1969, but the logistics for what became, as we’ll see, an opened-up and more ambitious program meant that the new version didn’t actually air until 1970… Final contractual arrangements for the new French Chef were signed by all parties in August 1970… Scenes in France were shot over four weeks in May–June 1970, with Paul and Julia Child and the production team traversing the country from Paris to Cannes and Nice, Marseilles, Burgundy, Normandy, and Brittany, and back again to Paris.” [24]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 223.

The second run would be in colour and have a new musical score.

What would turn out to be the last episode of The French Chef was broadcast on 14 January 1973.

By 1974 both Julia and Paul were weary of the commitment. Julia was now in her 60s, and Paul had had a few health problems:

“After due reflection, we have decided we do not want to commit ourselves to any series which would involve us in four or more months of program work, since that is just what we are now happily free of…. The end-result of long and serious discussions is that we have decided to bring to a conclusion our television life.” [25]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 228.

The French Chef and Europe

The Americans tried to market the show to the United Kingdom in the mid-1960s, but were not successful. The feeling was that the U.S. cooking measurements used by Julia would be a barrier to viewers.

“On February 15, 1965, Doreen Stephens, the head of the [BBC] Family Programmes (Television) Division, wrote… that the BBC wouldn’t be taking the show…. Stephens and others at the BBC seemed to feel that the fact of American measures, rather than metric European ones, combined with the Americanism’s in Child’s speech, meant that the show wouldn’t translate well. The BBC took a pass.” [26]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 210.

The show finally did air in the United Kingdom later in the 1960s, but it didn’t work well. The BBC aired the show in the afternoon, rather than the evenings, treating it as women’s fare (whereas in the U.S., evening showings brought in many male viewers.) It showed the episodes on random weekdays, with no publicity, and often pushed it aside for things such as horse-races. Within half a year it was cancelled.

“Child was so annoyed by what had happened that she wanted no further effort to get the show into the U.K. market.” [27]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Duke University Press. 2011. Page 210.

Julia Child is largely unknown in France, though some may remember her from the Meryl Streep movie named “Julie & Julia”. Some people in the French food world do know of her, but aren’t totally sure where to place her:

“… French commentators appreciated that, even though she made mistakes (she was, after all, not French but American, so culinary perfection could perhaps not be expected of her), Child still managed to cook well. They lauded her for the attempt to bring their cuisine to Americans, and they acknowledged that her sojourn in France, with its official (Cordon Bleu) study of culinary practice, had given her some claim to legitimacy in the realm. At the same time, she was congratulated by the French for admitting that the goal wasn’t perfect attainment of authentic French cuisine but an approximation that met American needs… ” [28]Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 198.

In 2009, a writer in Paris for the New York Times noted:

“Julia Child may have been America’s best-known “French chef,” but here in Paris few know her fabled cookbooks, let alone her name.” [29]Maia de la Baume, “A ‘French Chef’ Whose Appeal Doesn’t Translate Well in France,” New York Times, September 17, 2009, A6.

The few food authorities in France that do know of her feel that the recipes she presents were of an era, and are now dated and cliché:

“Some say she caricatured French cuisine in her book and cooking show, making it seem too heavy and formal… It’s the vision of a revisited France… Julia Child’s cuisine is academic and bourgeois… It shows that in America, the cliché of beef, baguette and canard farci remains.” [30]Maia de la Baume, “A ‘French Chef’ Whose Appeal Doesn’t Translate Well in France,”

It’s perhaps noteworthy that no French translation has ever been made of her cookbooks:

“No [French] publisher has published [a French] translation of The French Chef Cookbook, which brought together the recipes made in her eponymous show, nor of her very popular Mastering the Art of French Cooking in two volumes… Or perhaps it is simply felt that the French have no cooking lessons to receive from a pure Californian!” [31]Pham, Anne-Laure. Julia Child, qui c’est celle-là? Paris, France: L’Express. 13 August 2012.

It may also be that Julia Child, in Mastering the Art of French Cooking, attempted to translate recipes with restaurant-level complexity for use in home kitchens. But, says Clotilde Dusoulier, a French food blogger at Chocolate and Zucchini, “Most home cooks in France would not make such an elaborate version of what is supposed to be a simple stew.” They would reach instead for a simpler domestic version, such as that found in “Je sais cuisiner” by Ginette Mathiot. [32]Moskin, Julia. A Boeuf Bourguignon in (Gasp!) Five Steps. New York Times. 25 August 2009.

Julia Child remains largely unknown in France, and this does not look likely to change.

Have Julia Child’s recipes aged well?

Mastering the Art of French Cooking is an epic work, covering the preparation of classic French dishes in great detail.

Some critics, though, say it hasn’t aged well. One writer for Slate Magazine said that “the book has a preserved-in-aspic feel to it.” [33]Schrambling, Regina. Don’t Buy Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Slate Magazine. 28 August 2009. Accessed January 2021 at https://slate.com/human-interest/2009/08/why-you-ll-never-cook-from-julia-child-s-mastering-the-art-of-french-cooking.html

Another writer, Julia Moskin in the New York Times, points out what she feels is a fundamental problem of the book. Julia Child did not study enseignement ménager (“home economics”) in Paris, which would have trained to understand how the French did home cooking, but rather did a Cordon Bleu diploma, which is training for a restaurant career. Consequently, “‘Mastering the Art of French Cooking‘ is actually a translation of French restaurant technique to American home kitchens.” Rather than translate French home kitchen to American home kitchen, she translated French restaurant kitchen to American home kitchen.

Moskin notes that a French cookbook “Je Sais Cuisiner” (1932) by Ginette Mathiot, a home economist in France, is what she calls the French equivalent of “The Joy of Cooking“. That book is aimed at French housewives, not restaurants. Its recipe for boeuf bourguignon has nine ingredients and five steps. Child’s version, born out of restaurant tradition, has 18 ingredients and requires two pages of instruction. At least 3 of the ingredients must be prepared using separate recipes. [34]Moskin, Julia. A Boeuf Bourguignon in (Gasp!) Five Steps. New York Times. 25 August 2009.

It’s worth noting, though that Julia regarded Mastering almost as a textbook, and that her later cookbooks, such as From Julia Child’s Kitchen (1975) are much more relaxed and less onerous.

Another element is that the sheer quantity of animal fats used in the recipes is no longer in fashion, and in fact is seen as unhealthy:

“Readers who only recently opened the book [Ed: Mastering], and have been blogging and tweeting about it, have found some anachronistic surprises. “I’m looking at these ingredients going, Oh, sweet Lord, we’ll die… I know why all of the greatest generation has died of heart attacks”” [35]Clifford, Stephanie. After 48 Years, Julia Child Has a Big Best Seller, Butter and All. New York Times. 23 August 2009. Page A1.

The Julia Child dropped turkey / chicken myth

It’s a myth that Julia Child dropped a turkey / chicken on the floor in the TV set’s kitchen, picked it up, kept on using it, and said to viewers something along the lines of, “Remember, you’re alone in the kitchen.” (The same incident has been credited to Fanny Cradock.) It’s been an urban myth bandied about since at least 1989, and many people swear they remember watching it. For the PBS special Julia Child’s Kitchen Wisdom, her producer Geoffrey Drummond had to review more than 700 episodes of her shows, and says he never saw a dropped chicken or turkey.

Julia Child biographer Laura Shapiro offers this explanation:

“One day Julia taped a program with four different potato recipes, trying to move through them at a good pace. Standing at the stove over a large mashed potato cake in a skillet, she waited a little impatiently for the cake to brown on the bottom. She eyed the pan and shook it dubiously, then decided to flip the cake over anyway. Clearly she knew she was taking a chance. “When you flip anything, you just have to have the courage of your convictions, particularly if it’s sort of a a loose mass, like this.” She gave the pan a swift, practiced jerk. The potato cake rose heavily into the air and disintegrated, half of it spilling in shreds onto the stove. “Well, that didn’t go very well,” she observed steadily. “You see, when I flipped it, I didn’t have the courage to do it the way I should have.” Quickly she gathered up the pieces and reassembled them in the pan. “You can always pick it up,” she remarked as she worked. “You’re alone in the kitchen — who is going to see? But the only way to learn to flip things is just to flip them.”

“You’re alone in the kitchen — who is going to see?” This incident became legendary and then apocryphal, revised so many times in the telling that the original event disappeared. Julia dropped a chicken, Julia dropped two chickens, she dropped a turkey, a twenty-five pound turkey, a pig, a duck, and in each case blithely return[ed] them to their platters—all fantasies, but people recalled them joyfully.” [36]Shapiro, Julia Child. Page 119.

The film Julie & Julia

In 2009, a film titled “Julie & Julia” starring Meryl Streep as Julia Child was released. It was based on a web project by a woman named Julie Powell, who blogged her attempt to cook her way through Mastering the Art.

Powell’s project ran from August 2002 till August 2003. She called it “The Julie/Julia Project”.

By then, Julia Child had moved to Montecito, within hailing distance of Los Angeles.

The Los Angeles Times food writer Russ Parsons had known Child professionally for several years previous and whenever he passed through the Montecito area, he’d stop off to visit her. It was Parsons who printed off the “The Julie/Julia Project” blog and dropped it off for Child to read.

Child’s response to Parsons was, “She just doesn’t seem very serious, does she? I worked very hard on that book. I tested and retested those recipes for eight years so that everybody could cook them. And many, many people have. I don’t understand how she could have problems with them. She just must not be much of a cook.”

Child asked Parsons not to quote her, so he kept his silence about what she’d said until five years to the day after she died. [37]Parsons, Russ. Julie, Julia and me: Now it can be told. Los Angeles Times. 12 August 2009.

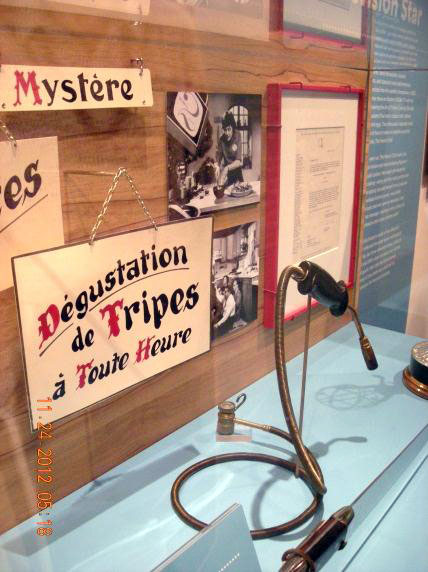

Julia Child’s blowtorch

Julia Child’s blowtorch From Julia Child’s Kitchen. National Museum of American History. Jameson Fink / flickr / 2012 / CC BY 2.0

Julia Child used a blowtorch made in West Germany. It is now at the National Museum of American History. She was one of the first celebrity cooks to cause a rush on a kitchenware item, in the way that Delia Smith would later do in England.

The museum’s entry for this blowtorch reads:

“Julia Child used this brass blowtorch and hose, attached to a fuel canister (not included in collection), for browning meringue (e.g., for Baked Alaska) and caramelizing crème brûlée. Julia introduced her students and fans to this tool adapted for the kitchen on her televised cooking shows. As an effective prop, it was also a new way of doing a technically difficult task. After watching Julia wield the blowtorch, aspiring cooks went to hardware stores and demanded blowtorches too. When smaller, specialized cook’s blowtorches became widely available, they replaced the large torches and tanks. This blowtorch was manufactured by the Bernzomatic Corporation in Germany.” [38]Blowtorch. National Museum of American History. Accessed January 2020 at

https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1143890

Julia Child and the LGBT community

Both Julia and Paul, according to biographer Laura Shapiro, were vigorously homophobic. She regularly referred to gay men as pansies, fags, homovipers, and “pedalo” (the French derogatory term.) She wanted more American men to be interested in haute cuisine, but was dismayed that as men finally came round, a number of them were homosexuals — she felt they would scare everyone else away, and spoke to her contacts in the food world about how to “defagify” the situation. Nevertheless, she was good friends for 25 years with James Beard, who had strongly supported her from the start, and in 1988, she appeared at an AIDS Benefit at Boston Garden held by the American Institute of Wine and Food. [39]Shapiro, Laura. Julia Child: A Life. New York: Penguin. 2009. pp. 135 – 144

Nevertheless, four years later, a $3 million dollar lawsuit was filed against Julia Child and the American Institute of Wine and Food which she helped establish. Daniel Coulter, 35, of San Francisco had been applying for the job of Executive Director of the Institute when the Institute’s chairwoman, Dorothy Cann, told him that Child was “rabidly homophobic” and that that would affect his ability to do his job there. [40]Gay Man Sues Child, Calls Her Homophobic. Deseret News, 3 February 1992. Richard Graff, a co-founder of the Institute with Julia, and a gay man, said that Coulter wasn’t hired simply because he didn’t have the qualifications for the job. Later, in 2001, Julia Child talked about the lawsuit in an interview: “The lawsuit was settled out of court because it would have cost us so much more to bring the case to trial,” Child explain[ed]. “That fellow got something like 30 to 40 thousand dollars, so it was probably worth his while. I have nothing against gay people. I work with them all the time. It doesn’t make any difference to me what you are.” [41]Kusner, Daniel. I got to talk to Julia Child once. Blog posting. 5 August 2009. Retrieved July 2012 from http://sniperslovenest.blogspot.com/2009/08/i-got-to-talk-to-julia-child-once.html

Literature & Lore

“Dining with one’s friends and beloved family is certainly one of life’s primal and most innocent delights, one that is both soul-satisfying and eternal. In spite of food fads, fitness programs, and health concerns, we must never lose sight of a beautifully conceived meal.” — Julia Child. The Way to Cook.

“If people aren’t interested in food, I’m not very much interested in them. They seem to lack something in their personality.” — Julia Child.

“Cilantro and arugula I don’t like at all. They’re both green herbs, they have kind of a dead taste to me. I would pick it out if I saw it and throw it on the floor.” — Julia Child, in 2002 television interview with Larry King.

When reached by telephone at 9 o’clock on a weekday morning, Julia Child said she and her husband Paul were having one of their favorite breakfasts — two oysters each and some orange juice. “Well, I do love tuna fish sandwiches,” Mrs. Child began, “and also chocolate ice cream sodas, peanut butter, which I resist, and those cute little goldfish crackers people serve with cocktails. And then, of course, hot dogs and hamburgers with onion, pickles and catsup.” — Mimi Sheraton. Food Junkie confessions. NY Times News Service. In Independent Press-Telegram. Long Beach, California. Wednesday, 19 May 1976. Page F2.

“Yes, a major American woman…. [part of] the first wave… the opposite of today’s victim psychology and so on. In the history of women, Julia Child obviously plays an enormous role. And the neglect of her career – you know, by the Feminist Establishment, by Women’s Studies, and so on–is very typical. This very achieving, practical woman – commanding as an admiral on a warship, for heaven’s sake, at the height of the British Empire – naturally doesn’t fit into the narrow view of the callow little Women’s Studies people.” — Paglia, Camille. In an interview with Chris Lydon [42]Lydon, Chris. Julia Child and the Sex of Cooking. 16 August 2004. Retrieved Jan 2009 from http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/lydondev/2004/08/16/julia-child-and-the-sex-of-cooking/

“Does anybody actually believe that Julia Child would be anything but a fossilized slab of butter in the Smithsonian if it weren’t for Julie Powell’s gauchely refreshing blogs and books?” — Alexandra Gill. The death of Gourmet. Toronto: The Globe and Mail. 6 October 2009.

“Child’s recipe for her signature boeuf bourguignon is three pages long and took as much effort and concentration as preparing a lecture – maybe more. But it earned no money and commanded no real respect or reordering of the domestic order. It was basically a hobby for ladies of leisure.” — Politt, Katha. Julie & Julia’s real-life women. Manchester. The Guardian. 6 September 2009.

Julia Child loved the hotdogs at Costco: “While living in Santa Barbara, the couple [Ed: Caroline & Ken Bates] were invited to a dinner cooked by celebrity chef Julia Child, who had a home there. “There were six of us, and she did everything,” says Ken. “She would come out of the kitchen with this big tray with all the dishes on it.” He also recalls how Child sat under the umbrellas at Costco in Santa Barbara, devouring the discount store’s hot dogs. “She was so very unphony,” says Caroline.” — Henry, Bonnie. Critic for now-gone Gourmet magazine savors the memories. Tuscson, Arizona: Arizona Daily Star. Monday, 28 December 2009.

Videos

Moments from Julia Child

Sources

Child, Julia. The Master of French Food Remembers Early Days in Paris. Paris: International Herald Tribune. 29 December 2000.

Child, Julia with Alex Prud’homme. My Life in France. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006.

De la Baume, Maia. A French Chef Whose Appeal Doesn’t Translate. New York: New York Times. 16 September 2009.

Pollan, Michael. Out of the Kitchen, Onto the Couch. New York Times. 29 July 2009.

Rosen, Michael. Interview with Julia Child for Archive of American Television Interview in Cambridge, Massachusetts. 25 June 1999.

Shapiro, Laura. The Trouble with Julie & Julia. New York: Gourmet Magazine. 30 July 2009.

Shapiro, Laura. Julia Child: A Life. New York: Penguin. 2009.

Spano, Susan. France was her entree, then the world was her oyster. Los Angeles: Los Angeles Times. 10 December 2006.

Stewart, David. Empowered to cook: Julia gives us the courage, shows us her joy. Takoma Park, Maryland: Current. 8 June 1998.

Tomkins, Calvin. Good Cooking. New York: The New Yorker. 12 December 1976.

References

| ↑1 | Julia’s pots and pans originally went to COPIA, the American Center for Wine, Food & the Arts, in Napa, California. When the center went bankrupt in December 2008, the Child family transferred them to the Smithsonian to re-unite them with the rest of the kitchen. Py-Lieberman, Beth. Julia Child’s Pots and Pans Are Back in Her Kitchen. Smithsonian Magazine. 29 July 2009. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Stewart, David. Empowered to cook: Julia gives us the courage, shows us her joy. Takoma Park, Maryland: Current. 8 June 1998. |

| ↑3 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Duke University Press. 2011. Kindle Edition. Page 139. |

| ↑4 | Paul wrote a letter that very first day to his brother; in it, he said they had “filet de sole.” Julia’s memory of what it was exactly at the first meal varied over the years. In “My Life in France” (p. 18) and in the fish chapter of “From Julia Child’s Kitchen,” she says “sole meunière.” In the piece she contributed to the 1988 book “Christmas Memories With Recipes” [Waxman, Maron L. Christmas Memories With Recipes. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. 1988.], and again in 2000 in Gourmet Magazine, she said it was duck. [per Laura Shapiro, Julia Child: A Life. New York: Penguin. 2009. P. 28-29] |

| ↑5 | ”The nation’s first captioning agency, the Caption Center, was founded in 1972 at the Boston public television station WGBH. The station introduced open television captioning to rebroadcasts of The French Chef with Julia Child… Captions on The French Chef were viewable to everyone who watched, which was great for members of the deaf and hard of hearing community, but somewhat distracting for other viewers. So the Caption Center and its partners began developing technology that would display captions only for viewers with a certain device.” — Allen, Scott. A Brief History of Closed Captioning. Mental Floss. 16 March 2015. Accessed June 2021 at https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/22685/brief-history-closed-captioning |

| ↑6 | Wilson, Craig. Celebs savor Montecito’s exorbitant vistas. USA Today. 30 January 2002. |

| ↑7 | Child, Julia with Alex Prud’homme. My Life in France. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. Page 236. |

| ↑8 | Mellowes, Marilyn. Julia! America’s Favorite Chef -Biography of Julia Child. PBS.org. 15 June 2005. Accessed July 2019 at http://www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/julia-child-about-julia-child/555/ |

| ↑9 | My Life in France. Page 238. |

| ↑10 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 129. |

| ↑11 | Shapiro, page 100. |

| ↑12 | My Life in France. Pp 240-242. |

| ↑13 | ”Those pilot programs have been lost.” Shapiro, page 100. |

| ↑14 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 129. |

| ↑15 | My Life in France. Page 243. |

| ↑16 | ”NET’s distribution of The French Chef began in the fall of 1964 with thirteen programs, numbered 14–26 (the original episode 13 had not been saved).” — Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 208. |

| ↑17 | Julia Child, 1998 introduction to The French Chef cookbook. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. [Re-issue, hardback edition.] |

| ↑18 | My Life in France. Page 246. |

| ↑19 | Child, Julia. The French Chef Cookbook. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2006. [Re-issue, hardback edition.] |

| ↑20 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 155. |

| ↑21 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 141. |

| ↑22 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 143. |

| ↑23 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 145. |

| ↑24 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 223. |

| ↑25 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 228. |

| ↑26 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 210. |

| ↑27 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Duke University Press. 2011. Page 210. |

| ↑28 | Polan, Dana. Julia Child’s The French Chef. Page 198. |

| ↑29 | Maia de la Baume, “A ‘French Chef’ Whose Appeal Doesn’t Translate Well in France,” New York Times, September 17, 2009, A6. |

| ↑30 | Maia de la Baume, “A ‘French Chef’ Whose Appeal Doesn’t Translate Well in France,” |

| ↑31 | Pham, Anne-Laure. Julia Child, qui c’est celle-là? Paris, France: L’Express. 13 August 2012. |

| ↑32 | Moskin, Julia. A Boeuf Bourguignon in (Gasp!) Five Steps. New York Times. 25 August 2009. |

| ↑33 | Schrambling, Regina. Don’t Buy Julia Child’s Mastering the Art of French Cooking. Slate Magazine. 28 August 2009. Accessed January 2021 at https://slate.com/human-interest/2009/08/why-you-ll-never-cook-from-julia-child-s-mastering-the-art-of-french-cooking.html |

| ↑34 | Moskin, Julia. A Boeuf Bourguignon in (Gasp!) Five Steps. New York Times. 25 August 2009. |

| ↑35 | Clifford, Stephanie. After 48 Years, Julia Child Has a Big Best Seller, Butter and All. New York Times. 23 August 2009. Page A1. |

| ↑36 | Shapiro, Julia Child. Page 119. |

| ↑37 | Parsons, Russ. Julie, Julia and me: Now it can be told. Los Angeles Times. 12 August 2009. |

| ↑38 | Blowtorch. National Museum of American History. Accessed January 2020 at https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1143890 |

| ↑39 | Shapiro, Laura. Julia Child: A Life. New York: Penguin. 2009. pp. 135 – 144 |

| ↑40 | Gay Man Sues Child, Calls Her Homophobic. Deseret News, 3 February 1992. |

| ↑41 | Kusner, Daniel. I got to talk to Julia Child once. Blog posting. 5 August 2009. Retrieved July 2012 from http://sniperslovenest.blogspot.com/2009/08/i-got-to-talk-to-julia-child-once.html |

| ↑42 | Lydon, Chris. Julia Child and the Sex of Cooking. 16 August 2004. Retrieved Jan 2009 from http://blogs.law.harvard.edu/lydondev/2004/08/16/julia-child-and-the-sex-of-cooking/ |